LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION IN THE BRAIN

SPECIFICATION:

LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION IN THE BRAIN, MOTOR, SOMATOSENSORY, VISUAL, AUDITORY AND LANGUAGE CENTRES; BROCA’S AND WERNICKE’S AREAS

RECAP AND ASSESSMENT

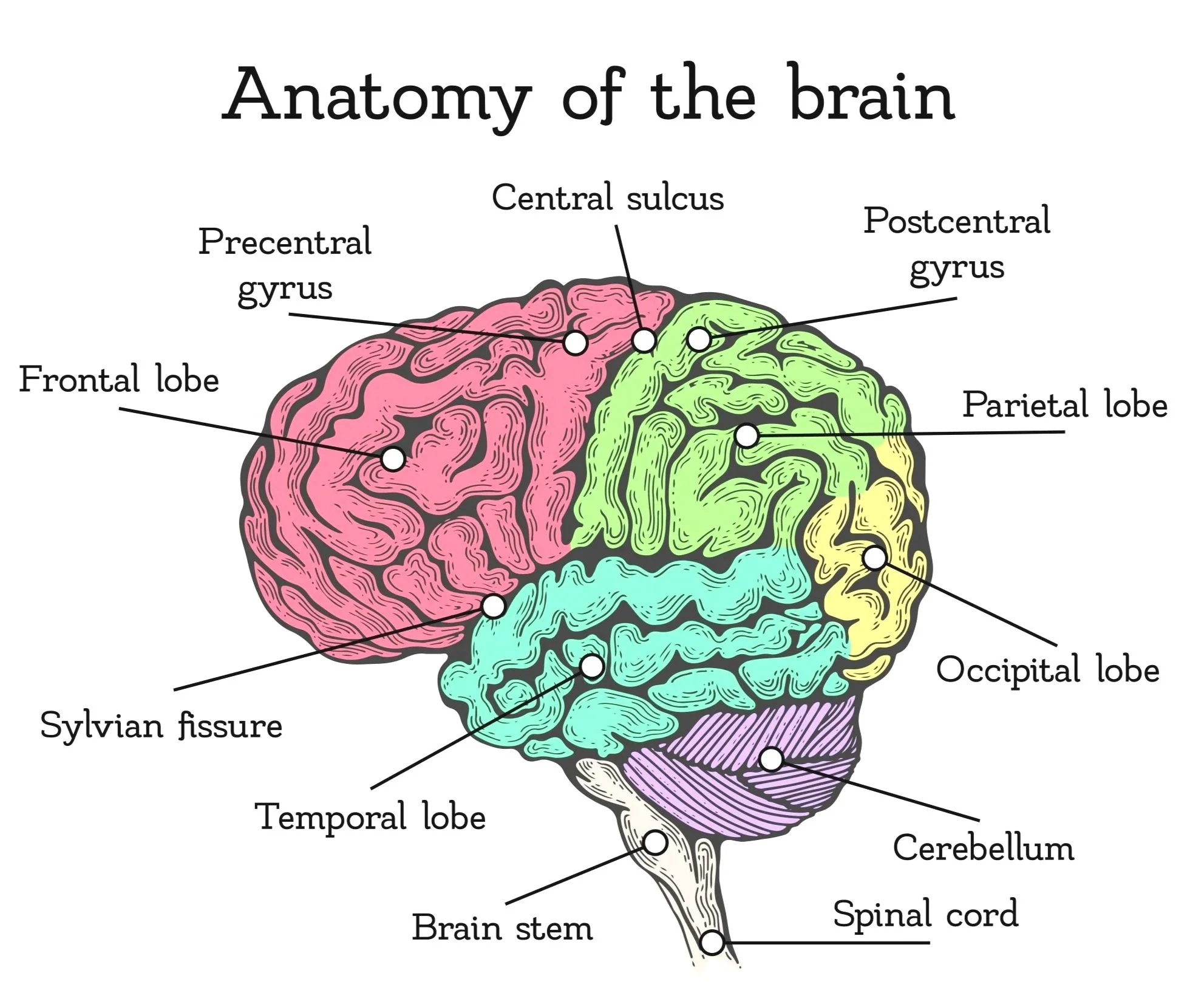

Before starting Localisation of Function, make sure you’re confident with the basics of brain structure and terminology. If you need a quick refresher on the central regions of the brain and what they do, visit BRAIN ANATOMY AND FUNCTION.

Once you’re ready to dive deeper, you can explore how this topic is assessed — including essay guidance, sample responses, and examiner-style tips — in ASSESSMENT MATERIALS FOR LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION.

KEYWORDS FOR: LOCALISATION OF BRAIN FUNCTION

AUDITORY CORTEX: Located in the temporal lobe, it processes auditory information.

CORTEX: General term for the outer layer of the brain's regions involved in processing information.

CEREBRUM: The most significant part of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, is responsible for higher-order functions.

CEREBRAL CORTEX: The outermost layer of the brain, responsible for higher cognitive functions.

COGNITIVE NEUROLOGIST: A specialist who studies how brain damage or neurological disorders affect cognitive functions like memory, language, and decision-making.

BRAIN LOBES: The four main lobes of the brain, each associated with specific functions:

BROCA’S AREA: A region in the frontal lobe associated with speech production.

FRONTAL LOBE: Responsible for reasoning, problem-solving, and motor control.

PARIETAL LOBE: Processes sensory information and spatial awareness.

DISTRIBUTED PROCESSING: The concept that brain functions are not isolated but depend on networks of interconnected regions working together.

EQUIPOTENTIALITY THEORY: This theory suggests that while some basic functions may be localised, higher cognitive functions are more distributed across the brain.

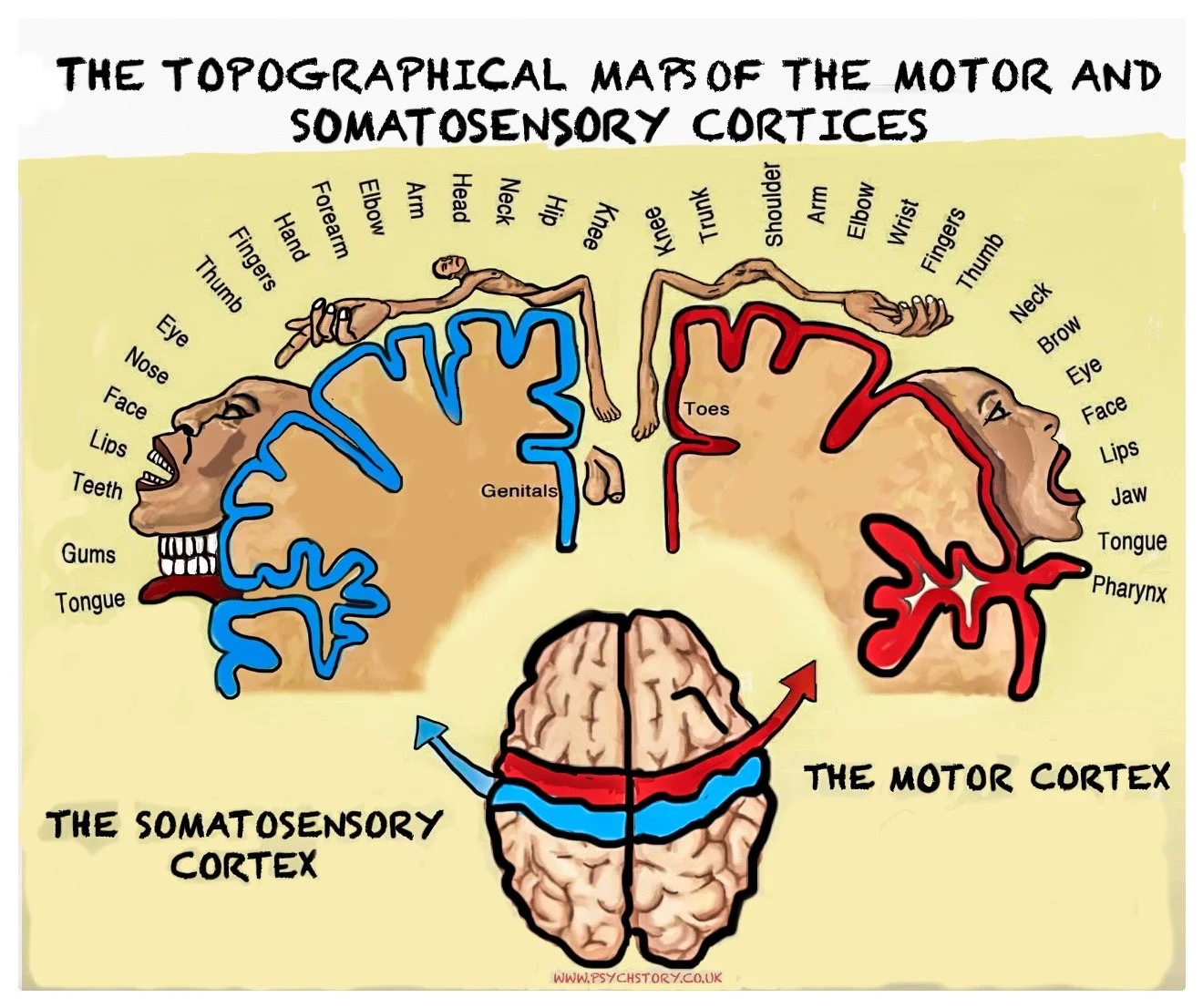

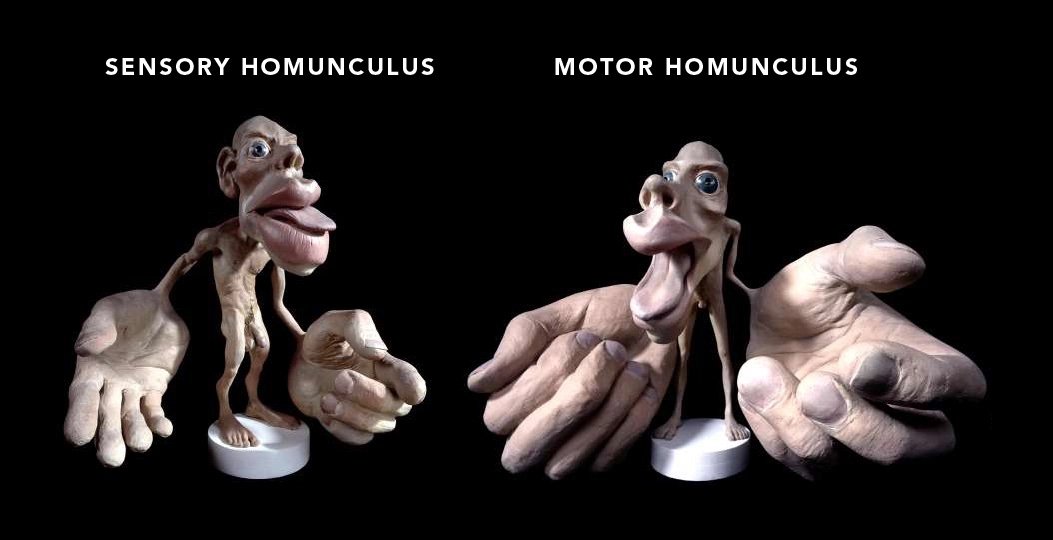

HOMUNCULUS MAN: A visual representation of how different body parts are mapped onto the somatosensory and motor cortices according to the amount of control or sensory input they receive.

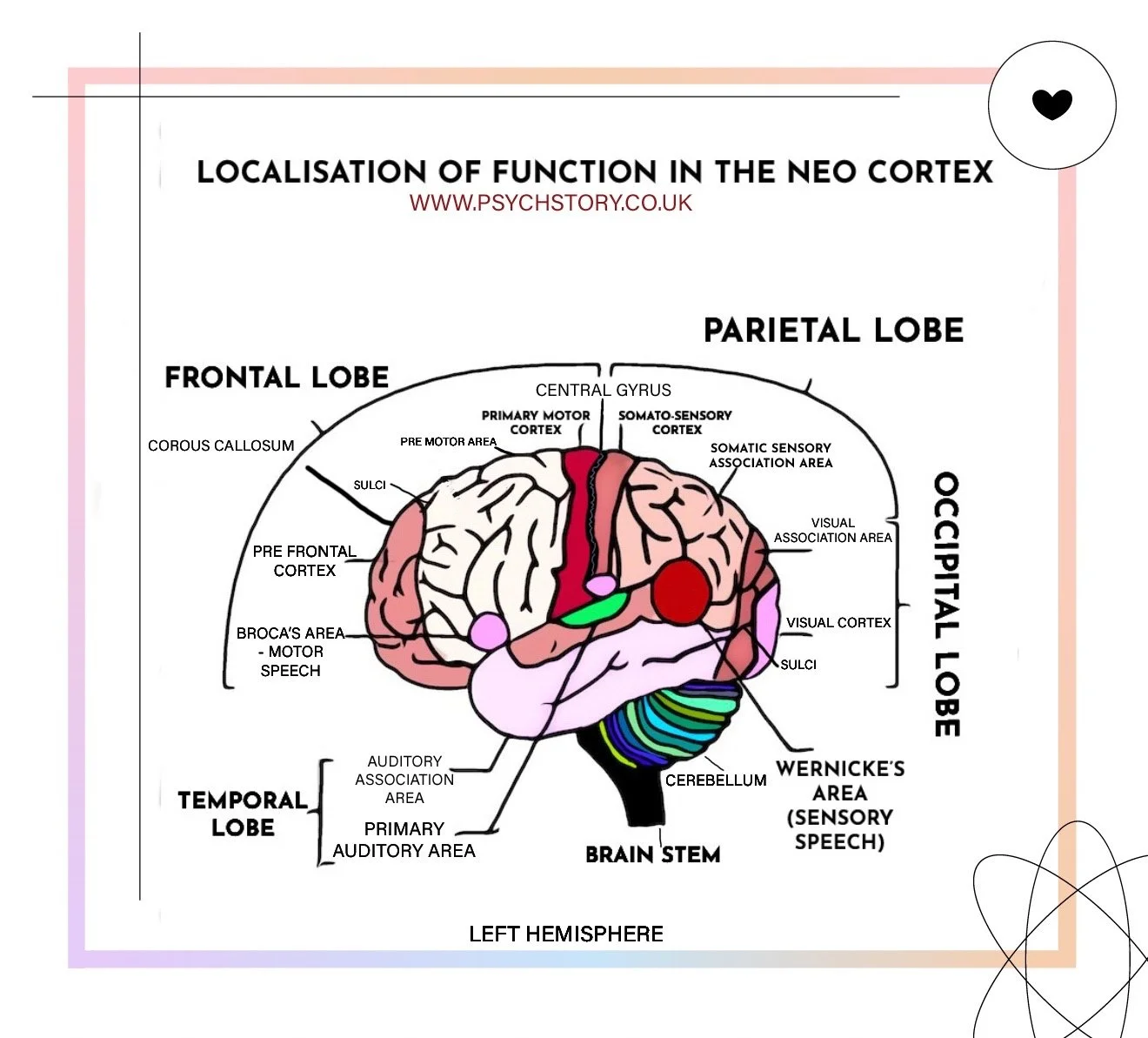

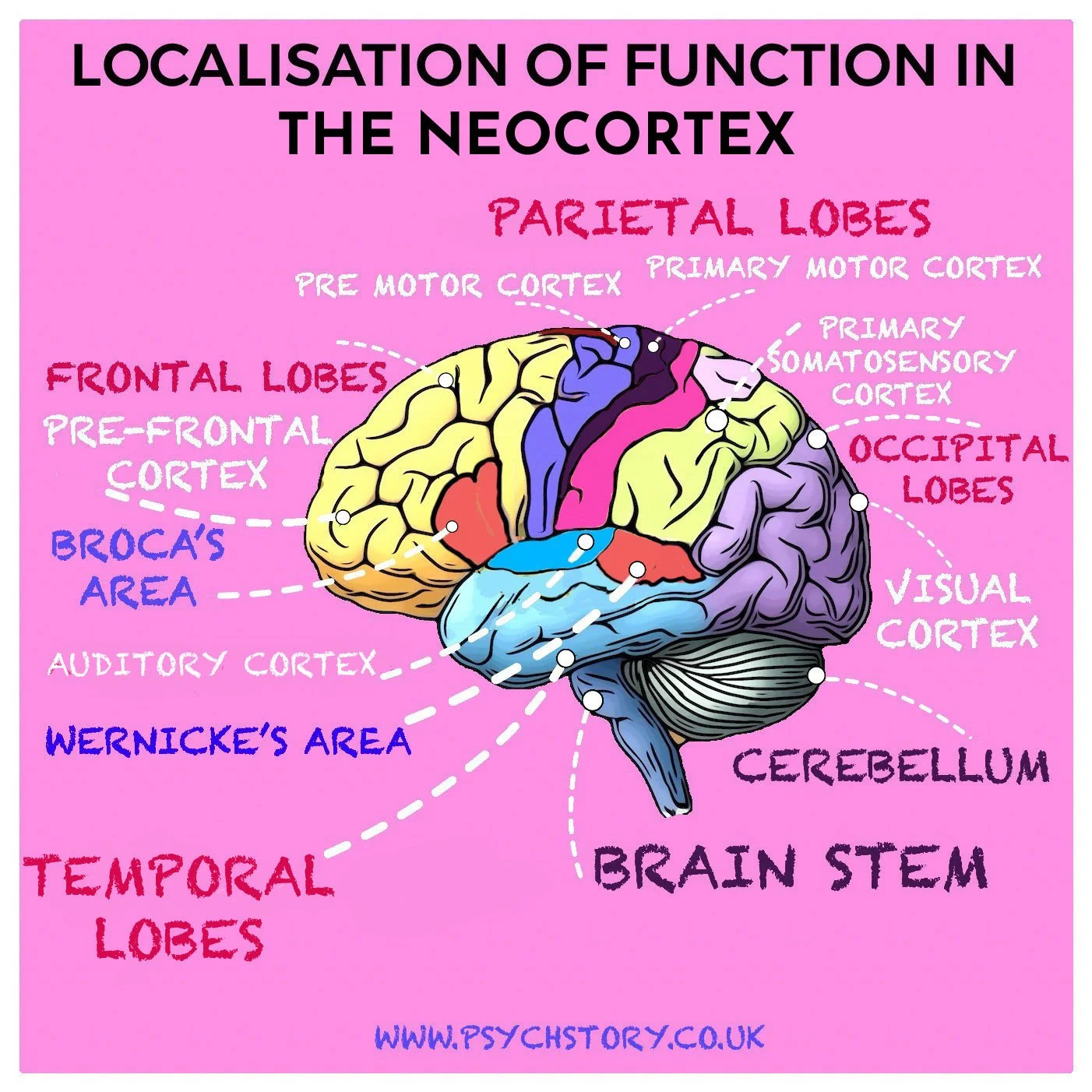

LOBES VS CORTICES: Lobes are the broader regions of the brain (e.g. frontal, temporal), while cortices are specialised areas within the lobes that handle specific tasks, such as the visual cortex for vision.

LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION: The theory that some regions of the brain are specialised for specific functions, such as language or movement.

MOTOR CORTEX: Controls voluntary movements and is located in the frontal lobe.

NEOCORTEX is the newest and most significant part of the cerebral cortex. It comprises approximately 90% of the human cortex and has six distinct layers.

NEUROIMAGING: Techniques such as fMRI and PET scans allow scientists to visualise brain activity and better understand the distribution of functions across different brain regions.

OCCIPITAL LOBE: Primarily involved in visual processing.

PHANTOM LIMB: The phenomenon where individuals who have had a limb amputated continue to feel sensations, including pain, in the missing limb, due to the brain’s sensory map.

PHRENOLOGY: A now-debunked theory that claimed the shape of the skull could determine personality traits and cognitive abilities by mapping bumps on the head.

POST-MORTEM: The examination of a body after death to determine the cause of death or study specific conditions, often used in brain research to examine the effects of brain damage on function.

PREFRONTAL CORTEX: The region at the front of the frontal lobe, associated with decision-making, personality, and social behaviour.

TEMPORAL LOBE: Key for auditory processing and memory functions.

SOMATOSENSORY CORTEX: Located in the parietal lobe, it processes somatosensory inputs from the body, including touch, pressure, and pain.

TOPOGRAPHICAL MAPPING: Refers to the way the brain organises the body's sensory and motor functions in a map-like representation, as seen in the motor and somatosensory cortices.

VISUAL CORTEX: Located in the occipital lobe, it processes visual information like shape, colour, and motion.

WERNICKE’S AREA: A region in the temporal lobe responsible for language comprehension

APPLICATION OF LOCALISATION OF FUNCTIONAL IN THE NEOCORTEX

WHAT IS THE TOPIC ABOUT?

LOCALISATION: "The act of identifying or pinpointing the exact location of something.” In this context, it means determining where in the brain specific processes or behaviours are situated. For example, the motor cortex is located on the precentral gyrus at the back of the frontal lobe.

FUNCTIONAL LOCALISATION: Extends beyond identifying a location—it defines what that area does. For example, Broca’s Area is localised within the left frontal cortex and is responsible for speech production.

Localisation serves a practical purpose. It helps scientists understand how brain damage or disease in one area can lead to the loss or impairment of certain functions. For example, damage to Broca’s area, a region associated with language, can result in speech difficulties. This theory also examines whether functions are consistently localised in the same brain regions across all members of a species. Scientists can better predict how the brain operates and responds to injury by pinpointing specific cognitive tasks to certain brain areas. This is vital in the treatment of brain injuries, strokes, and neurological disorders.

WHY “LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION IN THE BRAIN” IS A MISLEADING TITLE

Many exam specifications, including those from AQA, refer to this topic as the localisation of function in the brain, but this is scientifically imprecise. The brain consists of the Hindbrain, Midbrain, and Forebrain, each responsible for a range of automatic, regulatory, and sensory processes. When psychologists refer to localisation of function, they are not describing the entire brain. Instead, they refer to the Neocortex, the thin outer layer of the forebrain that governs higher mental functions such as reasoning, language, planning, and voluntary movement. In other words, localisation of function focuses specifically on the outer surface of the Cerebrum, the region responsible for the uniquely human aspects of thought and behaviour.

Brain – the entire organ; includes cortex plus deeper structures (brainstem, cerebellum, limbic system).

Cerebral cortex – the thin outer layer of the cerebrum; handles perception and voluntary movement.

Neocortex – the newest, six-layered part of the cerebral cortex found only in mammals; responsible for higher functions like language, reasoning, and complex perception.

ALTERNATIVE TERMINOLOGY

The phrase localisation of function in the neocortex is also known as CORTICAL LOCALISATION or CORTICAL MAPPING. These terms describe the process of identifying and mapping the precise functions of distinct cortical regions, such as motor control, sensory processing, or language production.

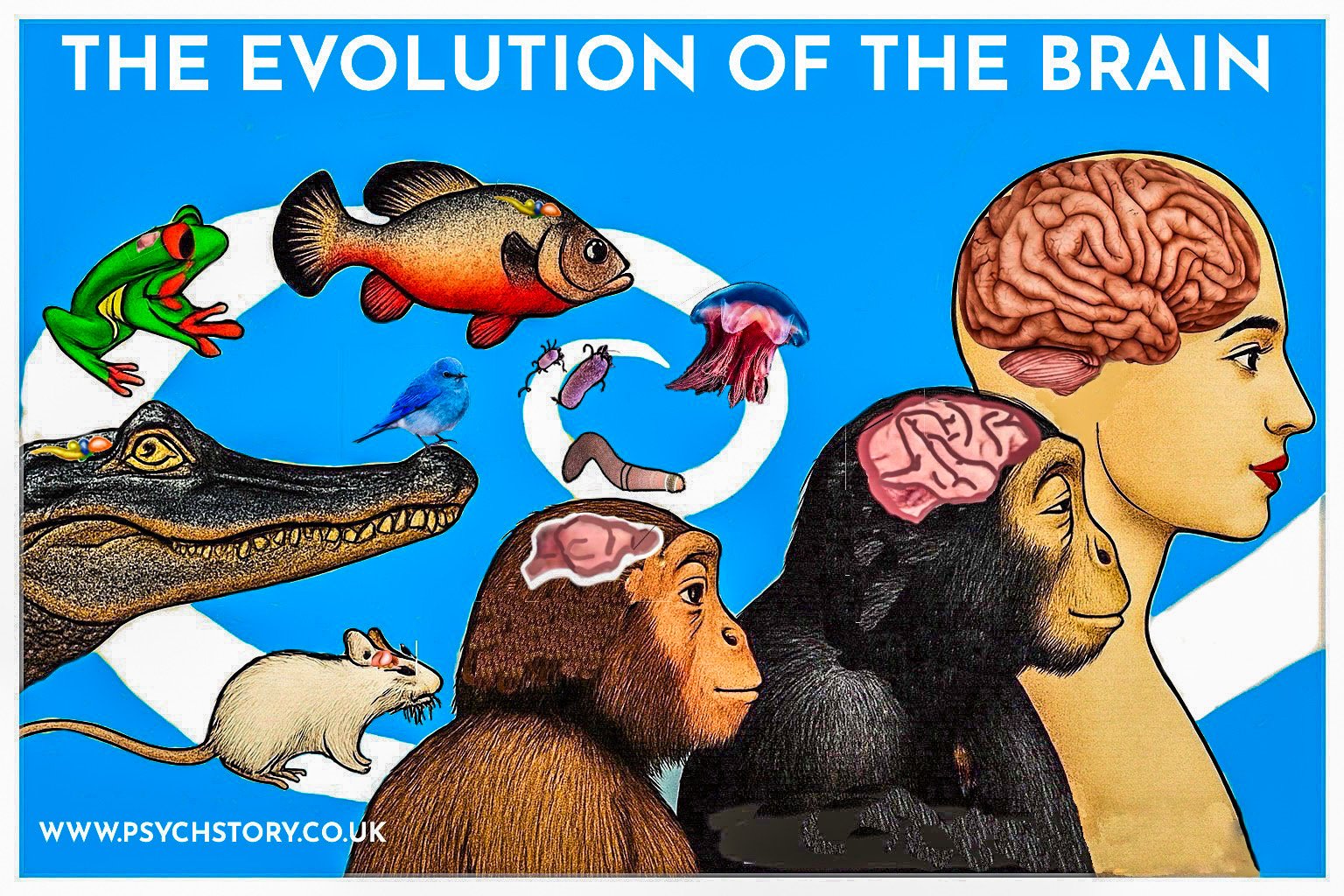

EARLY NERVOUS SYSTEMS: FROM NERVE NET TO NEOCORTEX

Same foundation, wild but wildly different renovations

Understanding how the neocortex is organised begins with seeing how it was built. The brain’s structure did not appear fully formed; it evolved step by step, with new parts added to old ones and each taking on specialised jobs. Tracing that journey — from the first nerve nets in simple animals to the layered neocortex of mammals — shows why the modern cortex is arranged the way it is. It explains how different regions came to perform distinct functions and why the human brain, though complex, still follows the same basic plan as our earliest ancestors.

Early nervous systems began with a nerve net, the basic foundation of the brain, which, over time, diverged and adapted to different environmental pressures. The earliest brains, such as the nerve net of a jellyfish, consist of a diffuse web of neurons capable only of simple reflexes: pulsing to swim, stinging in response to touch, and regulating heartbeat. There is no capacity for learning, memory, or planning — only immediate, automatic survival.

Over hundreds of millions of years, as environments became more complex and demanding, the early bilaterian nervous system was conserved and elaborated. Evolution added new layers of organisation, connecting and refining existing circuits rather than replacing them. Each adaptation enhanced perception, coordination, memory, or behavioural flexibility while maintaining continuity with the primitive central nervous system that first enabled integrated sensation and movement.

A good analogy for this is a bungalow house — a simple one-storey building with four walls and a roof that fulfils only the most essential needs. This basic structure provides the foundation for more complex dwellings. However elaborate those later designs become, they all retain the same core elements: walls, ceilings, and a central framework.

In the same way, every nervous system retains this ancestral architecture.

EVOLUTION SOLUTIONS

The human brain did not appear all at once. It developed through many small changes over millions of years as animals adapted to different environments. There was no single path — evolution tried many approaches. Some species changed in separate directions, others found the same solutions in different ways, and some even evolved together. In humans, culture itself became part of evolution, feeding back into the brain’s growth. These main patterns — divergent, convergent, co-evolution, and gene–culture coevolution — show how complex brains can arise from simple beginnings.

DIVERGENT EVOLUTION happens when a species that shares a common ancestor evolves along different paths as it adapts to new environments. For example, the forelimbs of mammals all have the same basic bone structure but have been reshaped for other purposes: wings for bats, flippers for whales, and grasping hands for primates. The exact process happens in the brain: species start with the same neural plan but emphasise different regions. A mole’s brain, for instance, devotes more area to touch, while an owl’s gives greater space to vision and hearing.

COVERGENT EVOLUTION happens when unrelated species face similar environmental demands and evolve similar solutions. Birds and bats, for example, both developed the ability to fly, even though their ancestors were very different. Likewise, dolphins and sharks both evolved streamlined bodies for swimming, even though one is a mammal and the other a fish. In the same way, dolphins, elephants, and humans have each developed large, folded brains capable of complex communication and problem-solving — not because they share a recent common ancestor, but because social living and cooperation favour intelligence.

In CO-EVOLUTION, two species influence each other’s development over time. The improvements of one create new challenges for the other. A classic example is the evolutionary “arms race” between bats and moths: bats evolved echolocation to hunt, and some moths evolved ears that detect ultrasonic calls, allowing them to dodge attacks. Each side drives the other’s sensory and neural adaptations.

Finally, GENE-CULTURE COEVOLUTION: THE HUMAN FEEDBACK LOOP, is found only in humans, describes how culture and biology mutually shape one another. When humans began farming, for example, people who could digest milk as adults had a strong nutritional advantage, so genes for lactase persistence spread quickly. Similarly, the ability to use language and tools created new pressures that favoured brains capable of planning, memory, and communication. Over time, these cultural practices and genetic changes reinforced one another, leading to the enormous and flexible human brain.

The human brain is the endpoint of a long architectural project. Each evolutionary step built upon an earlier design, adding new control systems, sensory maps, and layers of processing without ever discarding the old ones. To understand how this ancestral framework evolved into the modern cortex, it helps to trace the major milestones in nervous system evolution—from the earliest diffuse networks of nerve cells to the highly folded cerebral hemispheres of humans.

THE ROAD TO THE NEOCORTEX

The neocortex is unique to mammals. It has six layers of neurons, stacked and interconnected vertically to form columns of processing cells. These columns act like tiny circuits that handle one small piece of information at a time — such as the edge of an object, the direction of a sound, or the position of a limb — before combining that information into a complete perception.

The evolution of the nervous system reflects a steady increase in complexity, connectivity, and specialisation. Each stage adds new structures and refinements while retaining the original plan.

HOW THE NEOCORTEX EVOLVED

The cortex emerged gradually from older brain tissue called the pallium, which covered the forebrain in early vertebrates such as fish and amphibians. The pallium could process sensory information, but in a simple, unlayered way. As evolution advanced, this tissue began to divide into zones with more specialised roles. By the time mammals appeared, these zones had become distinct regions:

ARCHICORTEX — the oldest region, seen today in the hippocampus, is involved in memory and navigation.

PALEOCORTEX — a slightly newer region linked to smell and emotion.

NEOCORTEX — the newest and largest region, responsible for flexible thought, sensory perception, and reasoning.

Together, these regions form the cerebral cortex — the sheet of outer grey matter that integrates sensation, memory, and action. The neocortex is the most recently evolved and most elaborate part of the brain. The cortex is not a new invention but a refined extension of ancient neural structures.

To see how this architecture took shape, we can trace the key milestones in nervous system evolution, from the simplest nerve nets to the layered forebrains of mammals.

THE FIRST BLUEPRINT

Early animals, such as jellyfish, had only a nerve net — a loose weave of nerve cells that coordinated pulsing and movement but lacked a central control centre.

Example species: jellyfish, sea anemone, hydra.

THE FIRST COORDINATION SYSTEM

Flatworms and simple chordates acquired a spinal cord, a central line of communication connecting the ends of the body. This was the first wiring trunk through which information could travel quickly.

Example species: planarian worm, amphioxus (lancelet).

THE BRAINSTEM: AUTOMATIC CONTROL

As vertebrates evolved, part of the spinal cord enlarged to form the brainstem. This became the body’s life support system, managing heartbeat, breathing, and basic reflexes — functions that must never fail but do not require thought.

Example species: lamprey, hagfish.

THE HINDBRAIN: MOVEMENT AND BALANCE

The next addition was the cerebellum, a structure that fine-tuned motion and posture. Fish used it to swim efficiently; later species used it for walking and grasping.

Example species: bony fish, amphibians.

THE FOREBRAIN: SENSING AND LEARNING

The forebrain grew to process incoming sensory information, such as sight, smell, and touch and link it with memory and learning. It created the first flexible behaviour, the ability to change based on experience.

Example species: amphibians, early reptiles, birds.

THE CEREBRUM: DECISION MAKING

In reptiles and mammals, the forebrain expanded into the cerebrum, the large dome of tissue that makes up most of the human brain. Here, information from the senses is compared, decisions are made, and voluntary movements are initiated.

Example species: lizard, mouse, human

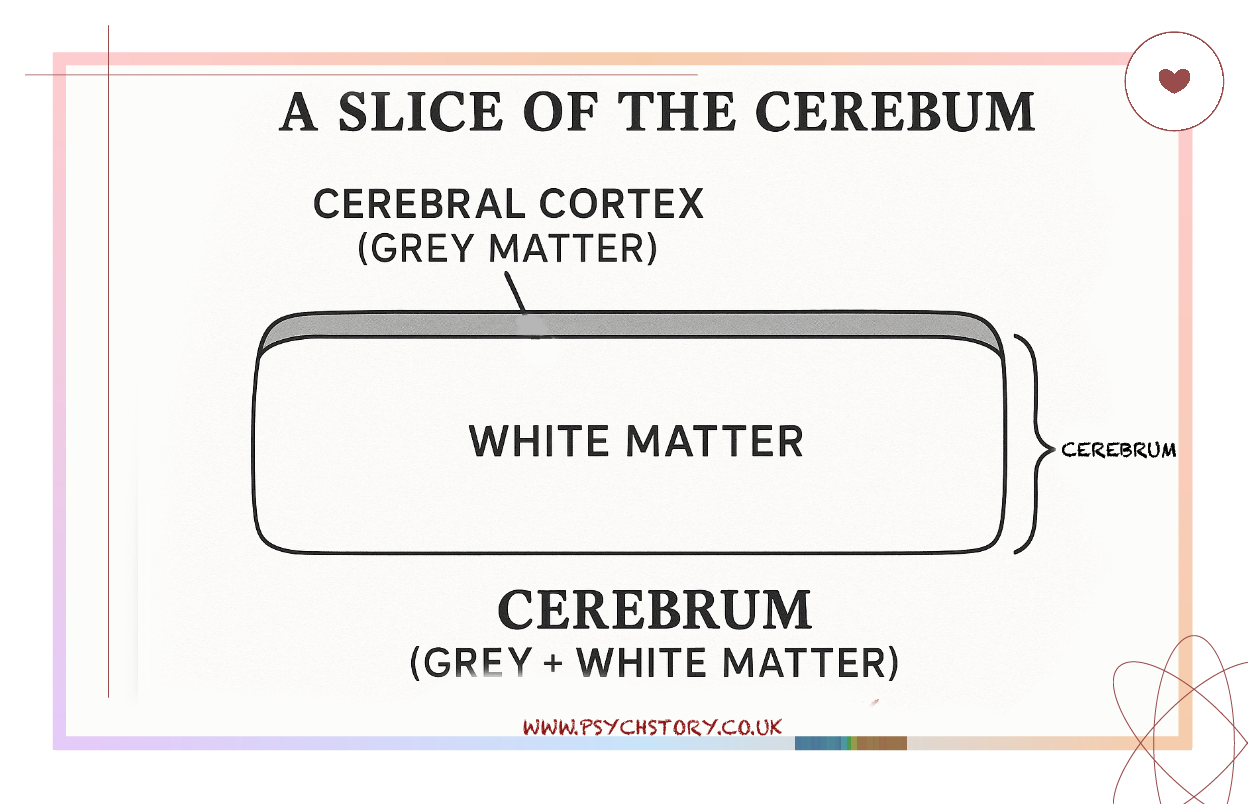

THE EMERGENCE OF THE CEREBRAL CORTEX

In mammals, this layer looks like a thin sheet of grey tissue covering the brain’s surface, about two to three millimetres thick. It is the most familiar part of the brain — the wrinkled surface seen in diagrams and models — and it enables complex, flexible behaviour.

When we talk about the cortex, we mean the outer layer. The word comes from the Latin corticis, meaning “bark,” because it covers the organ beneath it, just as bark covers a tree.

Many organs have cortices: the adrenal cortex on the adrenal glands produces hormones, and the renal cortex on the kidneys filters blood. So, “cortex” by itself means outer covering.

The cerebral cortex, however, refers specifically to the outer layer of the cerebrum, the most significant part of the brain. It is made mainly of grey matter — the cell bodies and dendrites of billions of neurons responsible for processing, integrating, and generating information. It looks like a thin sheet of grey tissue covering the brain’s surface, about two to three millimetres thick. It is the most familiar part of the brain — the wrinkled surface seen in diagrams and models — and it enables complex, flexible behaviour.

Beneath it lies white matter, formed by bundles of myelinated axons that link different brain areas, allowing rapid communication between them

THE NEOCORTEX

The cerebral cortex is responsible for perception, memory, thought, and voluntary movement. It is made of grey matter — the cell bodies and dendrites of billions of neurons that process and integrate information — supported by white matter beneath, which carries messages between cortical regions. In all mammals, the cortex forms the command centre for complex behaviour, turning sensory input into organised experience and purposeful action.

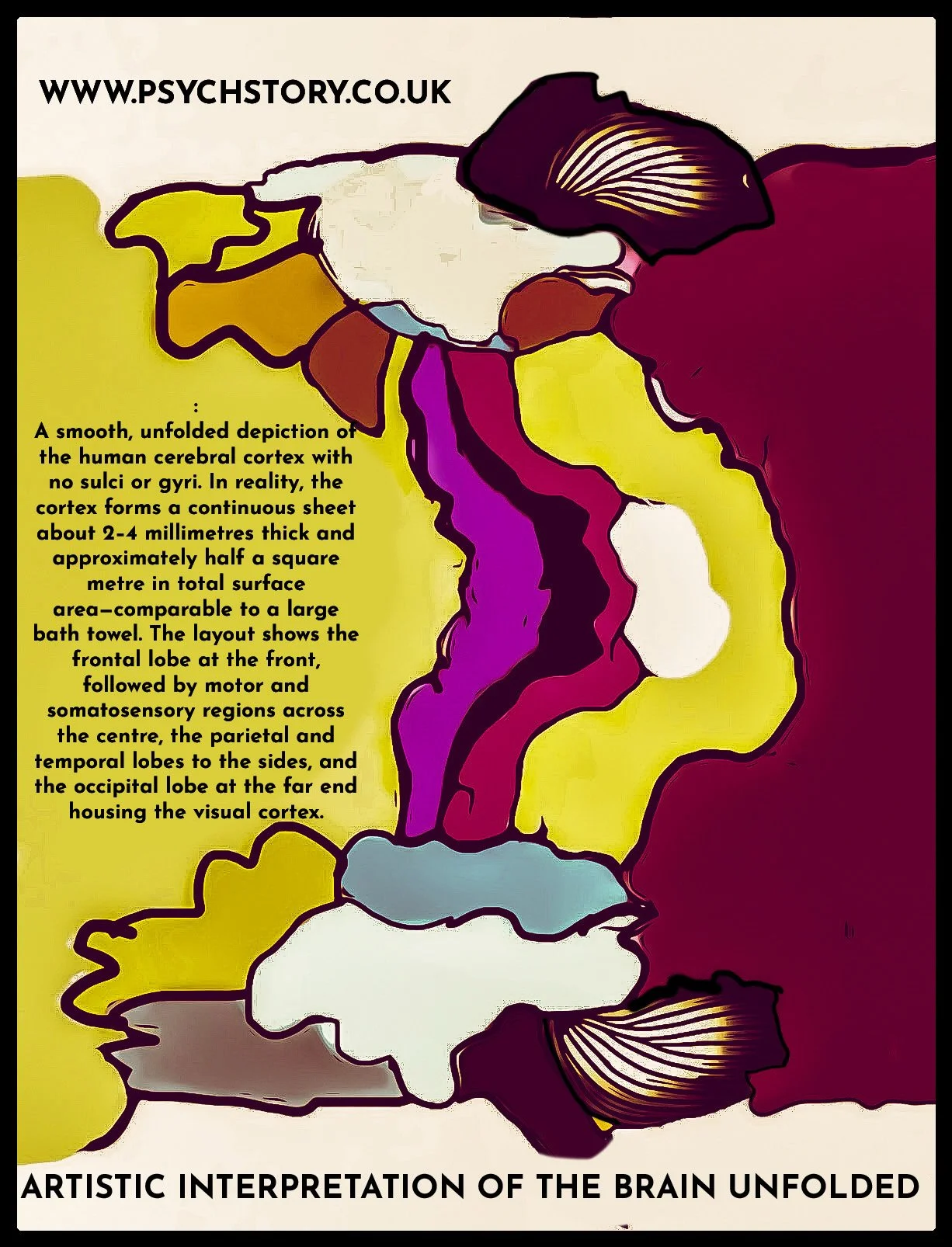

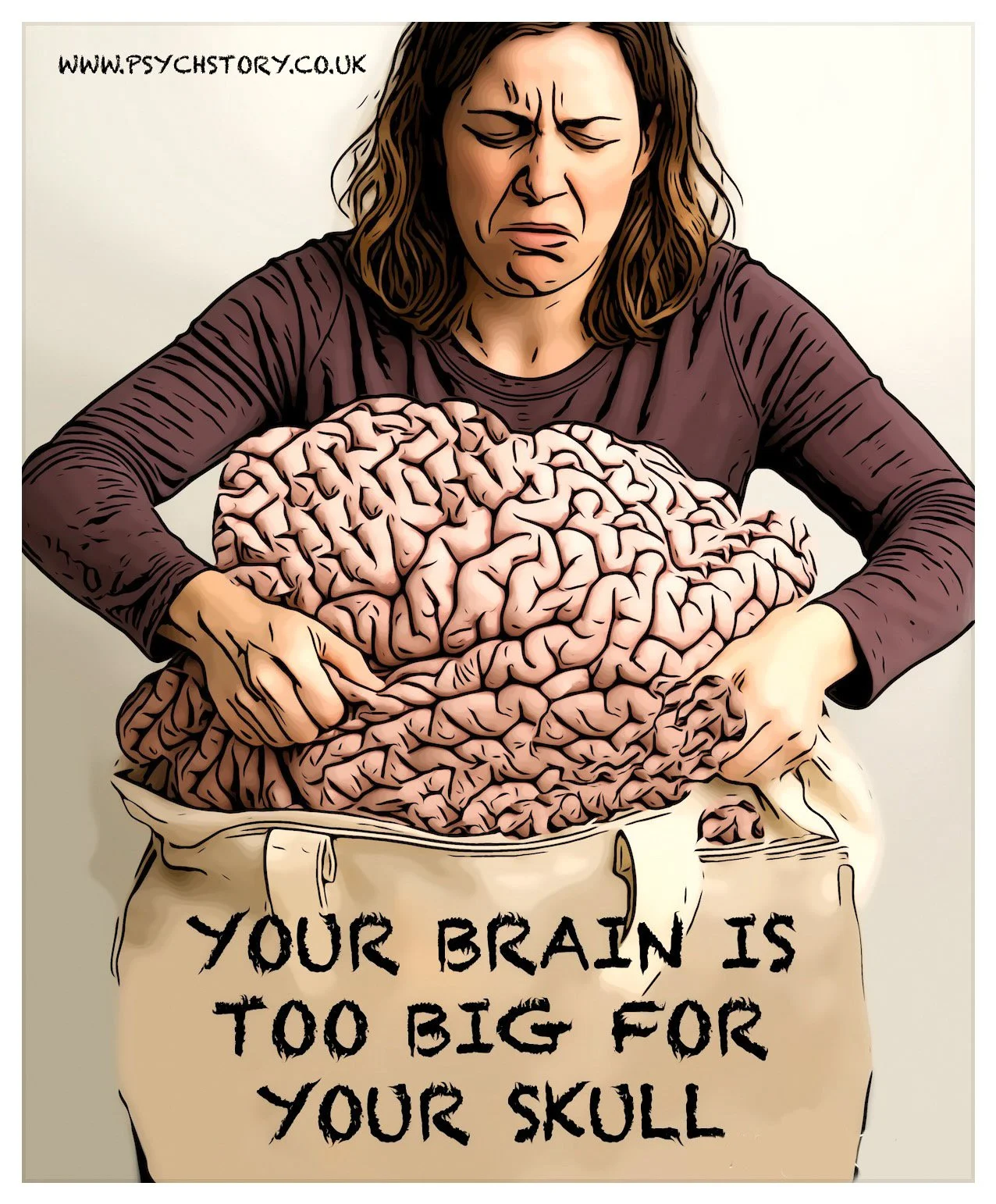

As evolution advanced, the cortex expanded and grew more specialised. Early mammals had small, smooth cortices sufficient for basic sensory processing and movement. But as environmental and social demands increased — the need to hunt strategically, communicate, care for offspring, or navigate group living — brain capacity had to expand. This created a structural problem: the skull could not enlarge indefinitely without making birth impossible.

As mammalian brains expanded, physical limits emerged. The skull could not enlarge indefinitely without compromising movement, balance, or the ability to be born. To increase processing capacity without increasing head size, the cortex folded in on itself, forming ridges (gyri) and grooves (sulci). This folding expanded the surface area and allowed far more neurons to fit within the same cranial space. The more folded the cortex, the greater its capacity for learning, sensory integration, and behavioural flexibility. It is like fitting a king-size bedsheet into a handbag — a crinkled mass.

In humans, this constraint became particularly acute. Bipedalism narrowed the pelvis and reduced the width available for childbirth, while the growing brain demanded more space. The only evolutionary compromise was to increase cortical surface area through further folding. Human infants are therefore born with large but still unfinished brains, which continue to grow and form connections long after birth. This trade-off between locomotion, reproduction, and brain size shaped both our anatomy and our extended period of childhood development — a biological investment in learning and intelligence.

Less intelligent mammals, such as shrews, have smooth, relatively simple cortices suited to instinctive behaviour. Mid-level mammals — cats, dogs, and hoofed animals — exhibit moderate folding, which supports more flexible learning and complex sensory integration. In highly social or intelligent mammals such as dolphins, elephants, whales, and great apes, the cortex expands dramatically. It folds into deep, intricate patterns, producing brains capable of planning, empathy, memory, and cooperation. These species also show high encephalisation quotients — brain size relative to body size — reflecting advanced cognition and social awareness.

From this same circuitry emerge abstraction and symbolism. The neocortex can detach thought from the immediate present, compare possibilities, and construct inner worlds of art, mathematics, morality, and belief. It is the source of narrative identity — the sense of a continuous “self” that remembers, plans, and interprets experience.

Earlier animals possessed forebrains that guided behaviour, but the mammalian neocortex added the power to imagine what does not yet exist, to reason beyond instinct, and to reflect on the fact of being conscious at all.

In humans, cortical expansion reached its peak. The prefrontal cortex became dominant, supporting foresight, language, moral reasoning, and abstract thought. Specialised neurons such as Von Economo cells emerged, enhancing rapid social perception and emotional intelligence. Together, these adaptations produced the uniquely flexible, self-reflective human mind.

SUMMARY

EARLY NERVOUS SYSTEMS: FROM NERVE NET TO NEOCORTEX

The brain evolved gradually, adding new structures to old ones over hundreds of millions of years.

The earliest animals, like jellyfish, had only a nerve net for simple reflexes and movement.

Flatworms developed the first spinal cords; vertebrates later added brainstems, cerebella, and forebrains for coordination and learning.

The cerebral cortex evolved from the pallium, an early sensory layer in fish and amphibians.

It is divided into three central regions:

ARCHICORTEX (hippocampus): memory and navigation.

PALEOCORTEX: smell and emotion.

NEOCORTEX: higher cognition, reasoning, and flexible thought.

Only mammals have a true neocortex, a six-layered structure of neuronal columns that processes sensory information and integrates perception.

As mammals evolved, the cortex expanded and folded (gyri and sulci) to fit more neurons into limited skull space — like folding a king-size bedsheet into a handbag.

Small mammals (e.g. shrews) have smooth cortices; mid-level mammals (cats, dogs, hoofed animals) show moderate folding; highly social mammals (dolphins, elephants, primates) have deeply folded, complex cortices.

In humans, folding reached its maximum due to bipedalism and restricted childbirth size, leading to larger but still-developing infant brains.

The expanded prefrontal cortex enabled language, planning, morality, and abstract reasoning.

From this same circuitry emerged self-awareness, imagination, and symbolic thought — the ability to think beyond instinct and reflect on one’s own mind.

Here is the link to the BBC Brain Story Documentary with Dr Susan Greenfield, Episode One: "All in the Mind":

Watch BBC Brain Story - Episode 1: "All in the Mind"

WHAT HAS BEEN LOCALISED IN THE NEOCORTEX

Click here to see an interactive brain map. PRESS

Now that we have examined what localisation of function means in the brain and discussed its importance, it is time to focus on the specific tasks that have been discovered and localised. These are primarily concerned with the following key areas:

MOTOR CENTRES

SOMATOSENSORY CENTRES

VISUAL CENTRES

AUDITORY CENTRES

LANGUAGE CENTRES: BROCA’S AND WERNICKE’S AREAS

Each of these areas plays a vital role in higher cognitive and sensory functions, and their localisation helps us understand the brain's structure and functioning in more detail.

THE HISTORY BEHIND LOCALISATION OF THE NEOCORTEX

The idea that different parts of the brain perform different functions emerged in the 19th century. Early neurologists such as Marc Dax, Paul Broca, and Carl Wernicke showed that damage to distinct cortical areas disrupted specific abilities. Dax first noted that speech loss was linked to left-hemisphere injury. Broca later identified a lesion in the left inferior frontal gyrus that impaired speech production, while Wernicke described another, more posterior region responsible for language comprehension. Together, their findings laid the foundation for the concept of localisation of function within the cerebral cortex.

At the same time, phrenology — the pseudoscientific belief that mental traits could be read from bumps on the skull — captured public imagination. Though discredited, it introduced the idea that behaviour might have a biological basis in specific brain regions, indirectly encouraging scientific investigation.

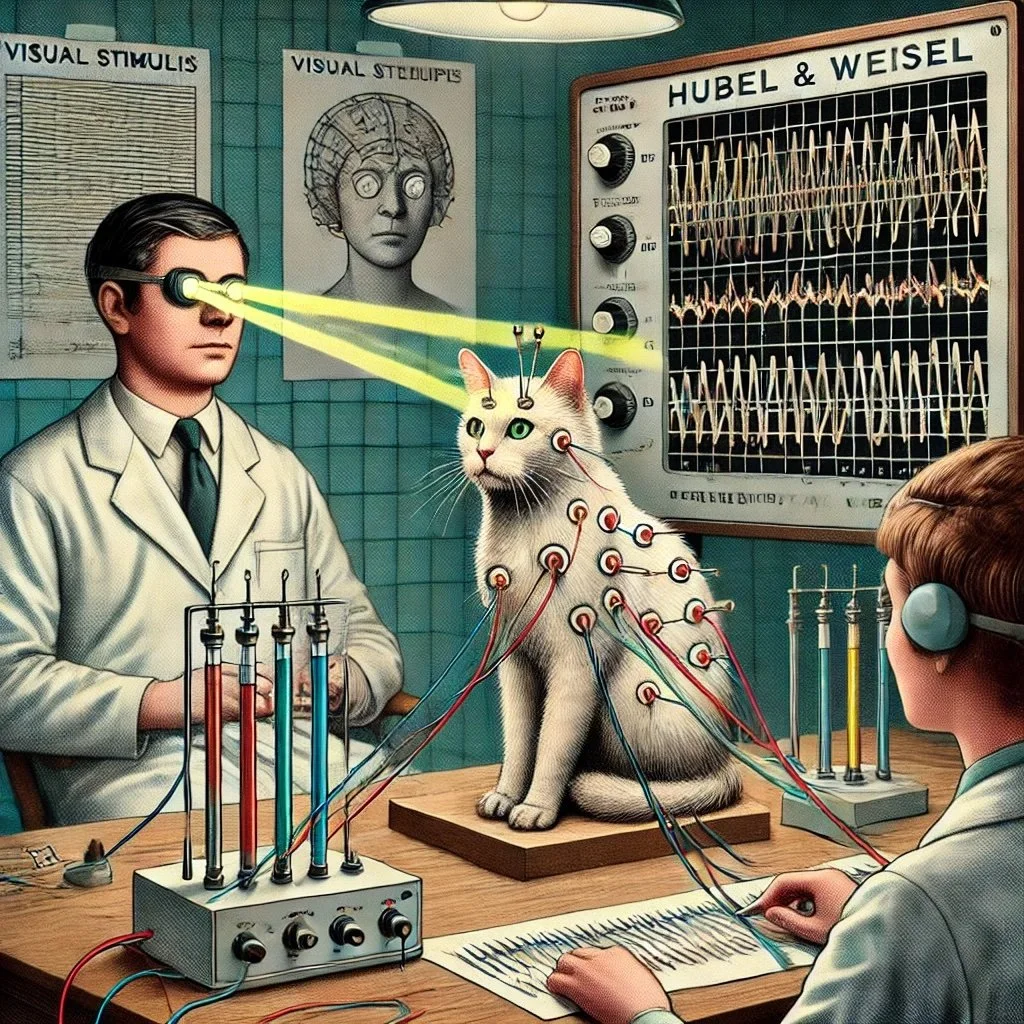

By the 20th century, advances in neurophysiology and animal research replaced speculation with evidence. In the 1960s, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel mapped the visual cortex of cats, revealing neurons tuned to specific orientations, movements, and patterns of light. Their discovery of feature detectors provided direct proof that the neocortex is organised into columns of specialised cells, each responsible for a precise computational role.

These studies transformed localisation from a clinical observation into a measurable biological principle: the neocortex is not a uniform sheet of tissue but a structured map of functionally distinct processing units.

TYPES OF RESEARCH USED TO IDENTIFY THE LOCALISATION OF FUNCTIONS IN THE NEOCORTEX

Before we delve into the different areas of the brain that have had their location and function identified, it is useful to familiarise yourself with the research methods used in this field. This is because much of what we know about localisation of function has come from the methods scientists have used to study the living and damaged brain. Each technique—whether post-mortem examination, electrical stimulation, lesion and ablation studies, psychosurgery, or modern brain imaging—has contributed unique insights into how specific cortical regions control particular behaviours. Understanding how this evidence was gathered will make it easier to evaluate the strengths and limitations of localisation research later on

CASE STUDIES

When first glancing over the range of techniques used to study localisation of brain function, the list appears diverse — and it is. Post-mortem examinations, electrical stimulation, ablations and lesions, psychosurgery, accidents, disease, EEGs, and modern brain scans have all contributed to mapping the brain. Each method tells part of the same story but from a different angle, revealing how specific areas of the neocortex control movement, sensation, vision, and language.

Although these techniques differ in precision and purpose, they all fall under the broad category of case-based research. This does not mean that a case study is itself a scientific method in the way that fMRI, EEG, or post-mortem analysis are. Instead, it describes the nature and scale of the data — usually small or unique samples — and the conditions under which the research can be ethically conducted. Case studies are idiographic by definition, concerned with individual or rare examples rather than with large, statistically tested groups. In the humanities and social sciences, this may be deliberate and phenomenological, focusing on lived experience and depth of description. In neuroscience, however, it is usually a matter of necessity: direct experimental manipulation of the human brain is impossible, so researchers must rely on naturally occurring opportunities provided by injury, illness, or surgery.

Historically, case-based evidence has combined a range of scientific techniques. Earlier work used post-mortem examination, crude ablation and lesion studies, and forms of psychosurgery carried out before the structure of the cortex was fully understood. These early methods were often imprecise but produced the first observable links between cortical damage and behavioural deficits. With advances in technology, the field expanded to include electrical stimulation during surgery, EEGs to record electrical activity, and later PET, MRI, and fMRI scanning to visualise activity in the living brain. Each method contributes differently: post-mortem analysis reveals structure after death; scanning reveals function in real time; lesions and psychosurgery provide causal inference about what happens when an area is disrupted.

Because of ethical and practical constraints, large-scale nomothetic studies are rarely possible in localisation research. Instead, a cumulative idiographic record has been built from hundreds of individual cases, each adding detail to the cortical map. In this sense, the case study operates as an umbrella framework that integrates multiple investigative tools — post-mortem analysis, neuroimaging, stimulation, and surgical observation — to examine how structure relates to function. Together, these diverse methods have provided converging evidence that the brain is functionally specialised yet interconnected.

FAMOUS HUMAN CASE STUDIES

While Broca’s and Wernicke’s patients are discussed elsewhere in relation to language, their cases also demonstrated links with the motor and sensory cortices. Broca’s area lies adjacent to the motor cortex and controls the movements of the lips, tongue, and jaw involved in speech production, showing how language function overlaps with motor control. Wernicke’s area, located in the temporal lobe near the auditory cortex, is closely associated with sensory processing and enables comprehension of spoken language.

MOTOR FUNCTION AND ACCIDENT CASES

Injury-based case studies — such as those involving car, motorcycle, or industrial accidents — have frequently revealed a direct relationship between damage to the motor cortex and loss of movement. Patients with frontal-lobe injuries that included the precentral gyrus often showed paralysis or loss of fine motor control in the body parts represented by the damaged area. These effects were contralateral — for example, right-hemisphere damage led to loss of movement on the left side of the body. This supports localisation of voluntary movement to the motor cortex.

SOMATOSENSORY FUNCTION AND TRAUMA CASES

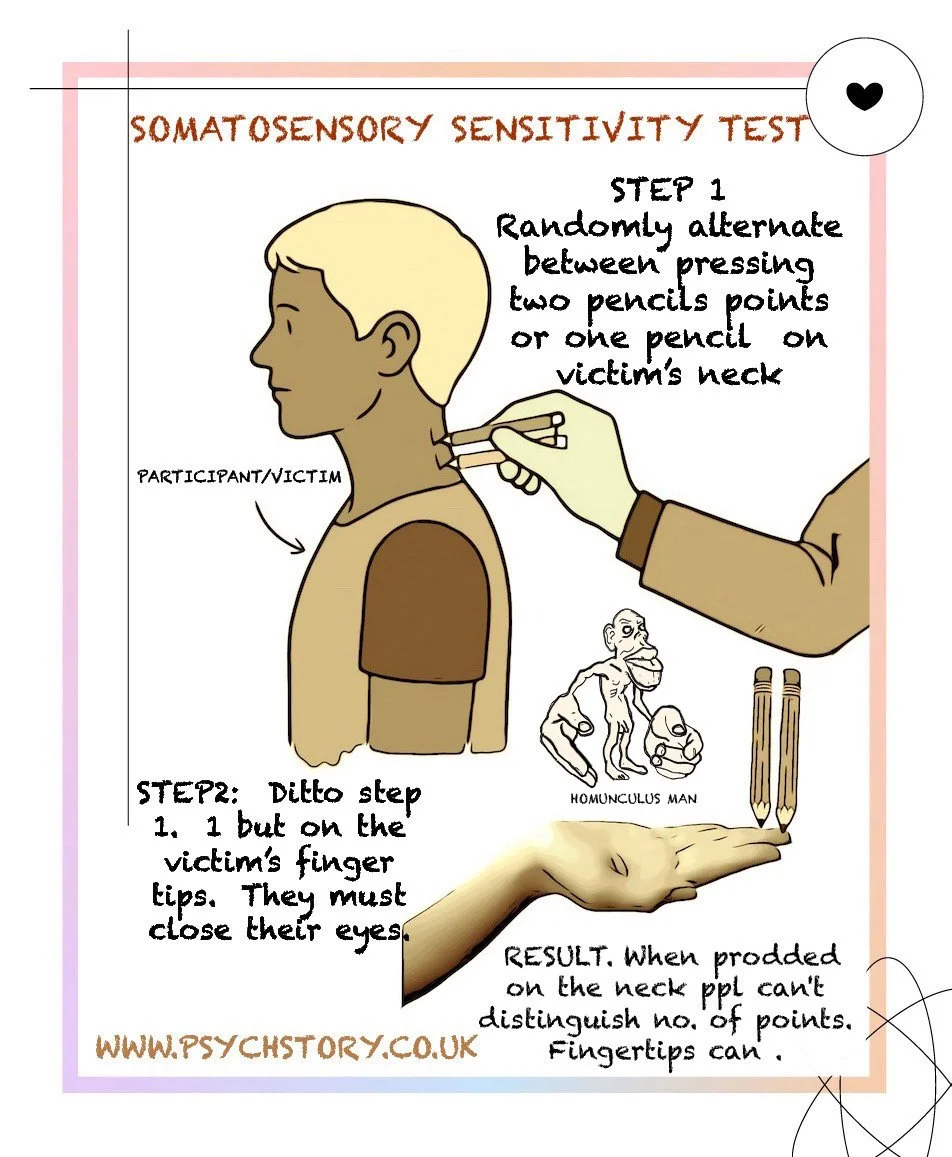

Similar patterns have been observed in parietal-lobe injuries resulting from falls, collisions, or blows to the head. Damage to the postcentral gyrus produced loss of tactile sensation, numbness, or an inability to distinguish between pressure and texture in the corresponding body region. Modern neuroimaging and post-mortem analyses have confirmed that these sensory deficits map precisely onto the area of cortical damage, reflecting the somatotopic organisation of the somatosensory cortex.

VISUAL FUNCTION AND ACCIDENTAL INJURY

Head injuries to the occipital lobe — often from car or sports accidents — have been linked to visual field loss or cortical blindness. Patients may lose vision in specific regions of the visual field while retaining other areas, depending on which region of the visual cortex is damaged. Post-mortem and modern neuroimaging studies confirm that these deficits follow a retinotopic pattern, meaning the visual field is mapped systematically across the cortex.

H.M. (1953) — ABLATION AND MEMORY LOSS

Henry Molaison (H.M.) underwent bilateral ablation (surgical removal) of the hippocampus to treat epilepsy. Although the operation was successful in controlling seizures, it caused permanent loss of the ability to form new long-term memories. H.M.’s case is distinct from traumatic injuries, as it involved deliberate surgical removal rather than accidental damage. Still, it provided robust evidence that the hippocampus is localised for memory formation rather than perception, movement, or sensation.

PHINEAS GAGE – A NOTE OF CAUTION

Phineas Gage is one of the most famous examples used to illustrate localisation of brain function. In 1848, an explosion drove a metre-long iron rod through his skull, destroying much of his left frontal lobe. Remarkably, Gage survived, but reports described a profound change in his personality and behaviour — from responsible and even-tempered to reckless, impulsive, and socially inappropriate. His case provided early evidence that specific brain regions are associated with distinct psychological functions, explicitly demonstrating the frontal lobe’s role in regulating personality, planning, and emotional control.

However, while Gage’s case is frequently cited in psychology textbooks as evidence of localisation, it should be used with caution. The AQA specification focuses on sensory, motor, and language areas — specifically the motor, somatosensory, visual, and Broca’s and Wernicke’s regions. The frontal cortex is not explicitly required for this topic. Therefore, Gage’s case is best used to illustrate the concept of localisation as a whole rather than as direct evidence for these specific cortical areas.

POST-MORTEM (AUTOPSY) STUDIES

TIME PERIOD:

Early 1800s – Present

PURPOSE:

To study the brains of deceased individuals and identify which areas were responsible for specific abilities or behaviours. Researchers examined structural damage and linked it to behavioural or cognitive symptoms recorded during the person's lifetime.

CONTEXT AND USE:

Before the development of scanning technologies, post-mortem studies were the primary method for investigating the localisation of function. Clinical notes taken during the person’s life were compared with the pattern of damage found at autopsy. From this, scientists inferred which brain regions were associated with specific abilities such as speech, movement, or vision.

WHAT IT SHOWED:

Postmortem work provided the first anatomical evidence that specific areas of the cortex are associated with particular functions. For example, damage to the left frontal region was consistently associated with loss of speech production, while damage to the occipital lobe was linked with visual impairment. It also revealed that the brain operates contralaterally — meaning each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body.

LIMITATIONS:

Post-mortem studies are descriptive and retrospective. They cannot show the brain functioning in real time or explain precisely how the damage produced the behavioural change. Every brain is structurally unique, and lesions rarely occur in isolation, so results cannot be generalised. The approach also assumes that changes seen after death reflect what was true during life, which is not always the case.

WHY IT DECLINED:

Advances in neuroimaging now allow researchers to observe brain activity in living individuals safely and repeatedly, using larger and more controlled samples. However, post-mortem analysis remains valuable for confirming structural findings, examining cellular and microscopic anatomy, and verifying imaging results.

INVASIVE METHODS OF INVESTIGATING THE BRAIN: ABLATIONS AND LESIONS

TIME PERIOD 1820s – 1960s

Ablations involve the surgical removal of large sections of the cortex, often performed in early research when little was known about brain function. Researchers used scalpels or blunt instruments to remove entire regions, then observed the resulting behavioural deficits. For example, removing the entire visual cortex rendered animals blind. However, this did not account for finer deficits, such as the inability to perceive movement or to recognise faces. Ablation was stopped once it was realised that cortical tissue contains approximately 30 million neurons per cubic millimetre, making the technique too crude to reveal detailed information. Lesions are minor, targeted injuries created using heat, chemicals, or electrical current to damage specific neural sites. Both methods were used to localise brain function by comparing behavioural changes before and after damage, revealing which cortical areas controlled movement, sensation, and vision.

Both methods were used in animal research to examine causal links between brain areas and behaviour. By removing or damaging parts of the cortex and observing the resulting deficits, researchers identified distinct functional regions: motor ablations produced paralysis or loss of coordination, parietal lesions impaired tactile discrimination and spatial awareness, and occipital damage caused visual blindness. These studies provided experimental support for the localisation of function and informed later human neuropsychological and neuroimaging research.

ABLATIONS: When large sections were ablated, animals often lost entire functions, such as movement, touch, or vision, demonstrating that these abilities were localised to specific cortical areas. This provided the first experimental evidence that brain functions are not evenly distributed across the cortex but are concentrated in specialised regions, laying the foundation for later human studies using neuropsychology and brain imaging.

MOTOR CORTEX: When specific parts of the motor cortex were ablated, the body parts controlled by those regions became paralysed or lost coordination. This showed that the motor cortex controls voluntary movement and that each section corresponds to a particular body region — a relationship known as somatotopic organisation. Recovery was often limited, indicating that motor control depends on precise neural pathways rather than general brain activity. Later research also found that stimulation of the same cortical areas could trigger movement, further confirming their motor role.

SOMATOSENSORY CORTEX: Ablations or lesions in the somatosensory cortex caused animals to lose awareness of touch, temperature, and body position. Because animals cannot verbally describe sensations, researchers inferred these losses from behaviour—such as failing to withdraw from heat, ignoring tactile stimuli, or showing uncoordinated limb use. The findings demonstrated that the somatosensory cortex receives and interprets information from the body in an organised, mapped pattern, with neighbouring cortical regions representing adjacent body areas.

VISUAL CORTEX: Lesions in the visual cortex resulted in blindness or specific visual deficits, depending on the site of damage. Removal of the entire visual cortex resulted in complete blindness, whereas partial lesions led to loss of specific visual field regions. These studies confirmed that the occipital lobe is essential for processing visual input, with different subregions specialising in features such as shape, orientation, and movement. This helped establish that vision is not a single function but a complex process distributed across multiple visual areas.

NON INVASIVE METHODS OF INVESTIGATING THE BRAIN: COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE SCANNING TECHNIQUES

Modern case studies often include neuroimaging, such as fMRI, PET, or CT, to assess brain activity and structure. These tools allow researchers to observe which brain regions are active during specific tasks or to visualise damage after injury. This approach maintains the idiographic focus of case studies while incorporating objective, measurable data.

ELECTRICAL STIMULATION OF ANIMALS

TIME PERIOD:

1870s – Present (refined)

PURPOSE:

To determine which areas of the brain control specific movements or sensations by directly stimulating the cortex with weak electrical currents.

Electrical stimulation was a breakthrough in mapping brain function, enabling researchers to observe the effects of activating specific cortical areas in real time. By applying small electrical currents to the exposed brain during surgery or in controlled animal experiments, scientists could determine which movements, sensations, or perceptions were elicited. Stimulating the motor cortex over specific body parts confirmed its role in voluntary control. Stimulation of the somatosensory cortex elicited sensations such as tingling or pressure in the corresponding body regions, thereby demonstrating its somatotopic organisation. When the visual cortex was stimulated, patients or animals reported flashes of light known as phosphenes, confirming its role in visual processing. Unlike ablations and lesions, this technique revealed function without destroying tissue, providing direct evidence for localisation and cortical organisation.

CONTEXT AND USE:

As physiological techniques improved in the late 19th century, electrical stimulation enabled researchers to observe the brain in action rather than relying solely on damage or post-mortem evidence. Small electrodes were placed on the exposed cortex of anaesthetised animals, and the resulting body movements or sensory responses were carefully recorded.

WHAT IT SHOWED:

This research demonstrated that stimulating one region of the neocortex produced a specific movement in the contralateral body part, whereas stimulating adjacent areas elicited related movements or sensations. It revealed that the cortex is functionally organised in an ordered and predictable way, leading to the identification of motor and sensory maps (known as homunculi).

WHY IT CONTINUED:

Electrical stimulation provided a reversible, controlled method for studying brain function without removing tissue or causing lasting damage. It provided the first experimental evidence of functional organisation in the cortex and remains useful in animal research today, with modern refinements enabling exact stimulation of individual neurons or circuits.

EEG (ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY)

Time period: 1920s – Present

Purpose: To record the brain’s electrical activity through electrodes placed on the scalp.

Context and use: The first non-invasive method for studying the living human brain. Measures voltage changes to detect brain waves and timing of neural responses.

What it showed: Revealed that brain activity changes during sleep, sensory input, and voluntary movement. It provided early evidence that specific wave patterns are linked to different states of arousal and cognitive processing.

Why it continues to be used: EEG remains widely used for its excellent temporal accuracy and safety, although its spatial precision is limited relative to modern imaging modalities.

PSYCHOSURGERY AND NEUROSURGICAL PROCEDURES

PURPOSE: To treat severe psychiatric or behavioural disorders by altering brain connections.

TIME PERIOD:: 1930s – 1970s

Context and use: Introduced when few psychiatric treatments existed. Procedures such as frontal lobotomies and amygdalectomies aimed to reduce aggression, anxiety, or obsessive behaviour.

From the 1930s onwards, psychosurgery and neurosurgery provided some of the most unmistakable early evidence for localisation of brain function. These operations, often experimental by modern standards, allowed researchers to observe live brain activity and its immediate effects on behaviour, emotion, and cognition. Over time, techniques became more refined, moving from crude lesioning to precise electrical stimulation and cortical mapping.

1930s–1950s: FRONTAL LOBOTOMIES

In the 1930s, António Egas Moniz developed the frontal lobotomy to treat severe psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression. The procedure involved cutting connections between the frontal lobes and deeper limbic structures. Patients often became calmer and less agitated, but many lost motivation, initiative, and emotional depth. These effects demonstrated the frontal lobes’ role in planning, personality, and emotional regulation.

1940s–1960s: AMYGDALA AND EMOTION (AMYGDALECTOMIES)

By the 1940s, neurosurgeons began removing or disconnecting the amygdala in patients with extreme aggression or anxiety. Following surgery, many showed a striking reduction in aggressive behaviour and fear responses, confirming the amygdala’s role in processing emotion and threat. Similar findings were later replicated in animal studies.

1953: HIPPOCAMPUS AND MEMORY (PATIENT H.M.)

In 1953, Henry Molaison (H.M.) underwent bilateral removal of the hippocampus to control epilepsy. The operation stopped his seizures but left him unable to form new long-term memories. This case revealed the hippocampus as essential for memory consolidation — the process of transferring information from short-term to long-term storage — and profoundly shaped understanding of memory systems.

WHAT IS SHOWED: Linked the frontal lobes and limbic system to emotional regulation, decision-making, and personality. It demonstrated localisation of these higher-order functions but also exposed the dangers of interfering with them.

WHY IT DECLINED: Effects were often unpredictable and irreversible, leaving patients apathetic or cognitively impaired. The rise of psychiatric medication and stricter ethical standards made psychosurgery largely obsolete. Many early findings on localisation of function, including the work of Broca and Wernicke, came from post-mortem examinations. While these have been instrumental in identifying brain regions associated with specific functions, several significant drawbacks remain. Post-mortem studies cannot capture real-time brain activity, making it impossible to observe how the brain functions during cognitive tasks. Furthermore, because they are conducted postmortem, there is no opportunity to measure plasticity or to assess how other brain areas compensate for damage. Additionally, individual differences such as bilingualism—which can lead to different development in Broca’s area—cannot be accounted for, making it difficult to generalise findings to the broader population.

NEUROSURGICAL PROCEDURES/ ELECTRICAL STIMULATION AND BLOCKING IN HUMANS (INTRAOPERATIVE MAPPING)

Time period: 1930s – Present

Purpose: To locate critical cortical areas during brain surgery and prevent accidental damage to speech, movement, or sensory regions.

CONTEXT AND USE: Developed in neurosurgery, particularly for patients with epilepsy or brain tumours. During awake operations, small electrical pulses are applied to exposed cortical areas while the patient performs tasks or responds verbally.

1950s–1970s: INTRAOPERATIVE ELECTRICAL STIMULATION

From the 1950s onwards, surgeons such as Wilder Penfield performed awake brain surgeries for epilepsy and tumours using local anaesthetics. Small electrical currents were applied to exposed cortical tissue to assess its function prior to removal. Stimulation of the motor cortex moved to specific body parts; stimulation of the somatosensory cortex caused tingling or touch sensations; and stimulation of the visual cortex produced flashes of light (phosphenes). This technique provided direct, real-time evidence for localisation of motor, sensory, and visual function and is still used today to avoid damaging critical areas.

1960s: BROCA’S AREA AND LANGUAGE LOCALISATION

Electrical stimulation or temporary inhibition of tissue near Broca’s area during awake surgery caused patients to pause or lose speech mid-sentence. This confirmed that the left inferior frontal gyrus is essential for speech production and allowed surgeons to operate safely around language centres.

1960s–PRESENT: TEMPORARY BLOCKING AND CORTICAL INHIBITION

Electrical or cooling probes were used temporarily to block neural activity during awake surgery. When an area was inhibited, the corresponding function—such as speech, movement, or sensation—ceased immediately. This reversible technique allowed surgeons to identify functional boundaries precisely and remains standard practice in neurosurgery today.

1960s–1970s: COMMISSUROTOMIES (SPLIT-BRAIN SURGERY)

In the 1960s and 1970s, surgeons treated severe epilepsy by cutting the corpus callosum, the bundle connecting the two hemispheres. Research by Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga on these “split-brain” patients revealed that the left hemisphere specialises in language and analytical thought. In contrast, the right hemisphere is dominant for spatial awareness and visual processing. These findings provided some of the most substantial evidence for hemispheric lateralisation.

WHAT WAS LEARNED

These decades of surgical investigation established several key principles:

The frontal lobes regulate emotion, planning, and personality.

The amygdala mediates aggression and fear.

The hippocampus is essential for memory formation.

The left hemisphere specialises in language.

The corpus callosum integrates information between hemispheres.

What it showed: Stimulation of the motor cortex moves; stimulation of the sensory cortex causes tingling or pressure; stimulation of the visual cortex produces flashes of light (phosphenes). Temporary blocking near Broca’s area can stop speech mid-sentence. This gave direct evidence of localisation in living humans.

Why it continues: Still used in modern neurosurgery, it remains one of the few methods that provides causal evidence of brain function in awake patients.

NEUROTOXINS

Time period: 1950s – Present (mainly animal research)

Purpose: To deactivate or destroy selected groups of neurons using targeted chemicals.

Context and use: Developed to study the function of specific neural systems more precisely than surgical lesions.

What it showed: Allowed researchers to study the effects of removing single neurotransmitter systems or small neural populations, helping to isolate fine control mechanisms in movement and emotion.

Why its use is limited: Mostly restricted to animal studies due to ethical and safety concerns in humans; newer non-invasive techniques can now study similar processes without cell destruction.

MODERN SCANNING AND COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

TIME PERIOD:

1970s – Present

PURPOSE:

To investigate both the structure and function of the living brain using non-invasive techniques that allow repeated, precise, and ethical observation.

CONTEXT AND USE:

From the 1970s onwards, new imaging technologies transformed localisation research. CT and MRI scans revealed detailed brain structures, while PET and later fMRI allowed researchers to observe brain activity in real time. By the 1990s, these tools had evolved into the field of cognitive neuroscience—the study of how cognitive processes such as language, memory, and perception are represented in neural systems. Researchers began integrating imaging data with electrophysiological measures (EEG and MEG), lesion evidence, and computer modelling to understand how networks of cortical areas work together.

WHAT IT SHOWED:

Modern imaging confirmed and extended earlier findings from post-mortem and lesion studies, demonstrating that complex behaviours arise from interactions among multiple specialised regions rather than from isolated centres. fMRI, in particular, enabled dynamic mapping of brain activity, revealing how different cortical areas communicate during sensory, motor, and higher-order cognitive tasks.

WHY IT DOMINATES TODAY:

Modern scanning and cognitive neuroscience together represent the most advanced and ethical approach to studying the human brain. They combine anatomical precision with functional measurement, allowing both structure and activity to be studied in the same individuals. This integration has replaced invasive historical methods and continues to refine our understanding of localisation and brain connectivity.

In recent research, methods such as fMRI, PET, and EEG have revolutionised our understanding of functional localisation by enabling real-time observation of brain activity without invasive procedures. However, even these methods have limitations. For instance, fMRI can show which brain areas are active during specific tasks. Still, it cannot establish causality—simply because a region is active doesn't mean it is solely responsible for the behaviour under study. Neuroimaging often reveals distributed neural activity, indicating that multiple areas are involved in even simple tasks. This challenges strict localisation theories, which suggest that each brain function is housed in a specific location.

LANGUAGE CENTRES IN THE BRAIN

BROCA’S AREA

BROCA’S AREA AND SPEECH PRODUCTION SIMPLIFIED

Have you ever wondered how you can speak, in other words, how the words you form become the distinct sounds that you and others recognise as language?

Have you ever thought about why your mouth moves when you speak? For example, is it simply a vessel that lets sound/words out, or do the movements of the mouth themselves shape the way those words sound?

QUIZ A

Tick the following statements you agree with:

A) Mouth movements in speech production are random; the mouth positions itself in spontaneous and unique ways to let sounds or words out.

B) The mouth could literally just open and close, and it would make no difference to how language was produced.

C) The mouth needs to make specific configurations to produce particular speech sounds.

D) Any person can sound native in any language at any age.

E) Sounding native in a language has a critical period.

The correct answers are C and E. The mouth must assume specific positions to produce particular sounds, and the ability to sound native in a language has a critical period.

TO DEMONSTRATE WHY ANSWER C IS CORRECT, TRY THE FOLLOWING EXERCISE

PART ONE

Say the letters T, B, K and TH out loud, one at a time. For each letter, please pay close attention to how your mouth positions itself for each sound. Where is your tongue? How wide is the opening of your mouth? How do your lips move?

If you are a native speaker of English, you should have noticed the following:

When you pronounce T, your tongue briefly taps the ridge just behind your teeth.

When you say B, your lips close completely before releasing the sound.

To produce K, you must spread your mouth very widely as the back of your tongue rises to touch the soft palate.

For TH, the tip of your tongue rests lightly between your teeth as air passes through, creating friction.

PART TWO

Now, try to make these same letter sounds with your mouth closed. What happens to your ability to produce certain letters?

Next, repeat the exercise, this time keeping your tongue completely still while saying the letters out loud.

You should have noticed that when your mouth is closed or when tongue movement is restricted, these letters become distorted or impossible to produce. This demonstrates that speech depends on the mouth being positioned in particular ways. Speech is not simply sound passing through an open mouth; it requires precise, learned configurations of the tongue, lips and vocal tract that shape air into recognisable speech.

QUIZ B

When your brain has mastered (or is mastering) the mechanisms of its first language or languages, what happens to that information?

Tick any of the following statements you agree with:

A) Speech production is not learned; it is just random and spontaneous because thought and learning are not physical processes. In other words, they have no form.

B) The mechanisms of language are learned and stored in an area of the brain called Broca’s area. They also connect with the motor cortex, which controls voluntary movement; Wernicke’s area, which processes comprehension; and the temporal and parietal lobes, which interact with long-term memory to store vocabulary and grammatical patterns.

C) Language production is conscious; a person consciously moves their mouth in specific ways to create speech.

D) Language production is unconscious and automatic; a person unconsciously moves their mouth in ways that create speech.

E) Babies babble for no scientific reason.

F) Babbling is a precursor to speech.

The correct answers are B, D and F.

HOW YOU LEARN TO SPEAK

But how do you learn this, and how can you speak without consciously thinking about it? Why can you pronounce words in your native language so easily, yet struggle with unfamiliar sounds such as the guttural Greek “γ”, the French “r”, the Arabic throaty consonants or the clicking sounds found in some South African languages?

From infancy, your brain begins building what linguists call phonetic representations—mental templates of the sounds specific to your native language. Newborns can distinguish all human speech sounds, but by around twelve months of age, their brains begin to tune to the phonemes (the most minor units of sound) of the language or languages they hear most often. This process, known as phonetic narrowing, means that infants lose the ability to easily perceive or reproduce sounds not used in their linguistic environment.

During this stage, infants experiment extensively with sound, producing repetitive syllables such as “ba”, “da”, and “ma”. What seems like playful babbling is actually a vital stage of neuromuscular development.

WHY DO BABIES BABBLE?

Babbling is a stage of early speech development in which infants produce repetitive or varied consonant–vowel sounds, such as ba, da, or ma. It is not random noise but a crucial period of neuromuscular and linguistic practice. Through babbling, babies explore how their vocal tract works and begin to map the relationship between movement (motor control) and sound (auditory feedback).

Babbling helps the brain train the motor circuits responsible for speech—particularly the connection between Broca’s area, which controls speech production, and the motor cortex, which governs the movement of the lips, tongue and jaw. Over time, auditory feedback from these experiments reinforces the correct movements for producing the sounds of the language or languages a child hears.

The brain, particularly Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe, learns to coordinate the dozens of fine motor movements required for speech, timing the activation of muscles in the lips, jaw, tongue and larynx. These coordinated actions form motor programmes that are stored and automatically retrieved whenever you speak.

A wider network supports these patterns.

Wernicke’s area is located in the posterior section of the superior temporal gyrus of the dominant (usually left) hemisphere, near the auditory cortex. It is responsible for language comprehension and speech interpretation. It also enables you to select the appropriate words when you speak. The motor cortex executes the physical movements involved in articulation. At the same time, the temporal and parietal lobes interact with long-term memory, allowing you to retrieve words, grammar and meaning almost instantaneously. Over time, these neural circuits become deeply ingrained through procedural memory, a type of non-declarative long-term memory responsible for unconscious skills such as walking, typing or riding a bicycle.

Once these speech motor programmes are established, they operate automatically. You no longer have to think about where to place your tongue or how wide to open your lips as you did as a toddler. Broca’s area retrieves and sequences the movements instantly.

BROCA’S APHASIA: MECHANISM, EFFECTS, AND RECOVERY

When the region known as Broca’s area, located in the left inferior frontal gyrus, is damaged through a stroke, head injury, or tumour, a person can lose the ability to produce fluent and coherent speech. Although they can still think clearly and understand what others say, the words they want to speak seem trapped in their minds, unreachable. This happens because Broca’s area is responsible for motor planning and speech articulation. It acts as a bridge between thought and movement, transforming ideas into a precise sequence of muscle actions in the lips, tongue, vocal cords, and respiratory system.

In a healthy brain, when a person decides to speak, Broca’s area assembles a motor “blueprint” of how each word should sound and passes that plan to the motor cortex, which then activates the muscles of the mouth and larynx in the correct order. When Broca’s area is damaged, the plan cannot be formed or transmitted appropriately. The muscles themselves still work, but they no longer move in the correct pattern to create intelligible words. This is why people with Broca’s aphasia can often move their mouths or utter single syllables but struggle to string words together. The result is slow, laboured, and fragmented speech, with missing grammatical connectors such as “is,” “and,” or “the.” For example, a sentence like “I am going to the shop” may come out as “I… go… shop.”

The loss of speech in Broca’s aphasia is not due to a lack of understanding. Wernicke’s area, located in the temporal lobe, processes comprehension and remains intact in most cases. The person can usually read and follow a conversation, but cannot form fluent responses. This mismatch between thought and expression can be intensely frustrating because the individual knows what they want to say, but cannot physically produce the words.

The neurological mechanism underlying this failure is a disconnection between cognition and motor output. The brain can still create the concept of a sentence, but Broca’s area can no longer convert that concept into a detailed sequence of movements. The signal is disrupted before it reaches the motor cortex, which controls speech muscles. It is as if the mind still writes the script, but the director can no longer cue the actors.

Despite the severity of the condition, recovery is often possible thanks to the brain’s plasticity—its ability to reorganise and form new pathways after injury. In the weeks or months following damage, other areas of the brain can take over some of Broca’s lost functions. Sometimes the right frontal lobe, which is the mirror image of Broca’s area, begins to compensate. In other cases, neurons surrounding the damaged site adapt to share the workload. This process, known as perilesional reorganisation, underlies most of the recovery observed during speech therapy.

Speech and language therapy (SLT) encourages this reorganisation through repetition and practice, helping new neural networks to take over the role of damaged ones. Therapies such as melodic intonation therapy, which uses rhythm and melody to engage right-hemisphere circuits, and constraint-induced language therapy, which requires the use of verbal communication, have been shown to strengthen alternative neural pathways. These treatments rely on experience-dependent plasticity, meaning the brain rewires itself in response to effort and practice.

Recovery from Broca’s aphasia depends on several factors, including the size of the lesion, the person’s age, and the intensity of rehabilitation. Smaller, partial lesions and younger brains tend to recover faster and more fully. However, even in severe cases, therapy can improve communication by helping patients use gestures, rhythm, or alternative speech circuits.

BROCA’S ASPHASIA IN SHORT

Broca’s aphasia occurs when the brain’s speech motor-planning area is damaged.

The person still possesses ideas, meaning, and understanding, but the “motor program” that turns those ideas into speech fails.

Speech becomes slow, halting, and grammatically broken, while comprehension remains intact.

Recovery depends on neuroplasticity, as undamaged regions of the brain—especially in the right hemisphere and adjacent areas—gradually take over functions of the speech network through practice and therapy.

SUMMING UP BROCA’S AREA

Speech production and articulation

Where is it? The left hemisphere, frontal lobe. The motor region in Broca’s area is close to the area that controls the mouth, tongue and vocal cords.

Research Type: Postmortem, near imaging, split-brain research, and electrical stimulation in surgery only ( animals can't speak, so no animal research here).

Broca’s Asphasia patient

RESEARCH FOR BROCA’S AREA:

Broca's and Wernicke’s areas rely on similar research methods, including post-mortem analysis, brain scans, split-brain research, and electrical stimulation during surgery. These methods are crucial for investigating the structural and functional aspects of these language regions.

PLEASE NOTE that research on language areas can only be conducted on humans because we are the only species with fully developed language capabilities. While animals may have forms of communication, they do not possess the complex structures and functions required for language comprehension and production, such as those found in Broca's and Wernicke's areas.

POST-MORTEM AND EARLY RESEARCH FINDINGS

1825 – JEAN-BAPTISTE BOUILLAUD

Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud was among the first to describe cases in which damage to the frontal lobes was associated with loss of speech. Although he did not localise language precisely, his research introduced the idea that speech production may depend on specific cortical regions. His findings provided one of the earliest pieces of evidence for functional localisation in the brain and directly influenced later studies by Broca.

1836 – MARC DAX

Marc Dax observed that patients with left-hemisphere damage frequently exhibited language impairments, whereas those with right-hemisphere damage did not. His work was pivotal in recognising hemispheric lateralisation — the idea that the left hemisphere plays a dominant role in language. Dax’s conclusions laid the necessary groundwork for Broca’s later theory of localisation and hemispheric specialisation.

1860 – PAUL BROCA

Paul Broca’s post-mortem study of a patient known as “Tan” marked a turning point in neurology. Tan could understand speech but could produce only one syllable. After Tan’s death, Broca examined his brain and found a lesion in the left posterior frontal lobe. Further examinations of additional patients with similar deficits revealed consistent damage to the same region. Broca concluded that this area — now called Broca’s area — was responsible for speech production.

Broca’s discovery provided direct anatomical evidence for localisation of function, showing that specific mental abilities could be traced to identifiable cortical regions.

1864 – JOHN HUGHLINGS JACKSON

John Hughlings Jackson extended Broca’s ideas through clinical observations of language disorders following brain injury. He proposed that speech loss results from damage to specific cortical networks rather than generalised impairment, reinforcing the notion that frontal lobe regions — particularly in the left hemisphere — play a specialised role in language.

CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH AND REINTERPRETATION

Although Broca’s area has long been linked to speech production, modern neuroimaging has refined this understanding.

Fedorenko (2012) used fMRI scanning to show that Broca’s area is not dedicated solely to language. She identified two functionally distinct subregions: one specific to linguistic processing and another engaged in broader cognitive tasks, such as problem-solving and reasoning.

This evidence suggests that Broca’s area functions as part of a flexible, distributed network that supports both language and higher-order cognition, aligning with modern models of functional integration rather than rigid localisation.Further evidence supports this reinterpretation. Hagoort (2014) proposed the Memory, Unification and Control (MUC) model, suggesting that Broca’s area unifies information from different brain systems — memory, syntax, and semantics — rather than simply generating speech. Dapretto and Bookheimer (1999) used fMRI to show that Broca’s area is also active during imitation and understanding of facial expressions, linking this activity to mirror neuron systems and the comprehension of intention. This indicates that Broca’s region contributes to both linguistic and social understanding.

In addition, Blank et al. (2002) found that activity in Broca’s area increases with sentence complexity, supporting its role in syntactic processing rather than just speech output. Tettamanti et al. (2005) found that reading or hearing action-related words (e.g., “kick” or “grasp”) activates motor areas connected to Broca’s area, suggesting a bridge between language and action representation.

Together, these studies show that Broca’s area is not a static “speech box” but a multifunctional hub that links language, thought, and social cognition. Its role is best described as integrative — coordinating meaning, structure, and intention — rather than purely localised or mechanical.

CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH AND REINTERPRETATION

Early research linked Broca’s area solely to speech production in the left hemisphere, but later findings reveal a far more complex and interactive role.

Roger Sperry’s split-brain studies (1968) first showed how crucial Broca’s area and the corpus callosum are for conscious language. When the corpus callosum was severed, information presented to the right hemisphere could not travel to Broca’s area in the left hemisphere, which meant it could not be verbalised. Participants could draw or select objects perceived by the right hemisphere but were unable to describe them verbally. This demonstrated that language, and perhaps conscious awareness itself, depends on communication between hemispheres and access to Broca’s area.

Later neuroimaging refined this view. Using fMRI, Fedorenko (2012) found that Broca’s area is not a single-purpose speech module but contains two interacting subregions — one specialised for language, the other for broader reasoning and problem-solving. This supports the idea that Broca’s area is part of a distributed, flexible network that integrates linguistic and cognitive processing.

More recent studies highlight the right hemisphere's role in communication. Regions opposite Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas process intonation, rhythm, and emotional tone — the prosodic features that give language meaning beyond words. These right-hemisphere systems work in tandem with Broca’s area to interpret sarcasm, humour, and emotional nuance.

Together, this body of research shows that Broca’s area is not an isolated speech centre but a key node in an integrated, bilateral network. It links thought to language, coordinates verbal and emotional expression, and enables the left and right hemispheres to work together to produce meaningful, socially attuned communication.

THE AUDITORY CORTEX

The auditory cortex is the region of the brain responsible for hearing and interpreting sound. It transforms simple vibrations detected by the ear into meaningful auditory experiences such as speech, music, and environmental sounds. It plays a key role not only in perception but also in language, communication, and memory.

LOCATION

The auditory cortex lies in the temporal lobe, primarily within the superior temporal gyrus (STG), and is hidden within the lateral sulcus, on a structure called Heschl’s gyrus. Each hemisphere contains its own auditory cortex, and both receive input from both ears, though each side responds most strongly to sounds from the opposite ear. This bilateral input allows precise sound localisation and depth perception.

STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION

The auditory cortex consists of multiple interconnected regions that process sound at different levels of complexity:

Primary Auditory Cortex (A1): The first cortical area to receive input from the thalamus (via the medial geniculate nucleus). It detects the fundamental physical properties of sound — such as pitch, loudness, and rhythm. A1 is organised tonotopically, meaning that neighbouring neurons respond to neighbouring sound frequencies, forming a map from low to high pitch across the cortex.

Secondary Auditory Cortex (A2): Integrates more complex features of sound, such as tone combinations, timbre, and changes over time.

Auditory Association Areas: Surround A1 and A2, and are responsible for higher-order analysis — recognising voices, identifying words or melodies, and linking sounds to meaning or memory.

HEMISPHERIC ASYMMETRY

The auditory cortex shows apparent functional asymmetry, especially in humans.

The left hemisphere is dominant for language and speech processing. It is specialised for analysing rapid temporal changes in sound—the rapid fluctuations that define syllables, phonemes, and word boundaries. This makes it crucial for understanding spoken language.

The right hemisphere is more sensitive to the pitch, tone, and rhythm of sound. It processes slower changes and the melodic contours of speech, music, and environmental noises. This hemisphere contributes to the emotional and prosodic (intonational) aspects of communication.

Although these differences are pronounced, both hemispheres work together continuously. The left extracts linguistic detail, while the right contributes intonation, rhythm, and affect — combining precision with nuance.

TOPOGRAPHICAL ORGANISATION

Like other sensory cortices, the auditory cortex is arranged in a systematic map. Instead of a body map (as in the motor or somatosensory cortex) or a spatial map (as in the visual cortex), it uses a frequency map — a layout called a tonotopic map. Lower frequencies are represented in one area and progressively higher frequencies in another, maintaining the order found in the cochlea of the inner ear. This organisation enables the brain to distinguish multiple pitches simultaneously, such as recognising harmony or speech amid background noise.

FUNCTION AND NETWORKS

The auditory cortex is not an isolated processor but rather part of a larger network that connects the temporal, frontal, and parietal lobes. It sends output to language regions such as Wernicke’s area in the left hemisphere, which interprets the meaning of spoken words, and to Broca’s area in the frontal lobe, which controls speech production. It also connects to limbic structures, including the amygdala and hippocampus, allowing emotional responses to sound and the storage of auditory memories.

PLASTICITY AND EXPERIENCE

The auditory cortex is highly plastic and shaped by experience, particularly early in life. Exposure to speech sounds during infancy helps refine phoneme discrimination, while musical training can expand and sharpen cortical frequency representations. Following hearing loss, adjacent frequency regions can reorganise to compensate, and in deaf individuals, the auditory cortex can repurpose itself to process visual or tactile input, demonstrating remarkable functional flexibility.

SUMMARY

Location: Temporal lobe, primarily in Heschl’s gyrus on the superior temporal gyrus, deep within the lateral sulcus.

Function: Processes and interprets sound — from fundamental pitch and volume to complex speech, music, and environmental patterns.

Organisation: Tonotopically arranged from low to high frequency; includes primary, secondary, and associative areas.

Asymmetry: The Left hemisphere specialises in speech and language; the right hemisphere processes tone, rhythm, and prosody.

Connections: Linked with Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas for language, and with limbic regions for emotion and memory.

Plasticity: Shaped by experience, learning, and sensory adaptation; capable of reorganisation after hearing loss

RESEARCH ON THE AUDITORY CORTEX

Understanding of how the brain processes sound has developed over more than a century through anatomical observation, animal research, surgical stimulation, neuroimaging, and clinical investigation.

1860s–1880s: THE LOCALISATION PRINCIPLE

The discovery that language functions were localised to specific cortical regions by Broca and Wernicke led scientists to question whether other sensory abilities, including hearing, might also have distinct cortical locations. In 1881, David Ferrier used electrical stimulation and ablation in monkeys and found that the temporal lobes were essential for hearing. When these areas were stimulated, the animals reacted as if they were hearing sounds; when the same areas were destroyed, they became unresponsive to auditory cues despite intact ears. This was the first demonstration that hearing depended on a specific cortical region.

1907: POST-MORTEM AND EARLY RESEARCH FINDINGS

In 1907, Pierre Marie and Auguste Lhermitte published Sur une nouvelle circonvolution temporale chez l’homme in Revue Neurologique, describing a distinct ridge in the superior temporal gyrus, later named Heschl’s gyrus. They compared its microstructure with that of auditory areas in animals and found the same dense layering and connections to auditory pathways. They also linked temporal-lobe damage in this region to hearing loss despite normal ear function. From this, they concluded that Heschl’s gyrus was the primary auditory cortex, the first cortical station for analysing sound frequency and pitch.

1930s–1950s: ELECTRICAL MAPPING IN ANIMALS

Using fine electrodes, Clinton Woolsey and colleagues recorded neural activity from the auditory cortices of cats and monkeys. They discovered that adjacent neurons responded to adjacent sound frequencies, forming a tonotopic map from low to high pitch. This proved that the auditory cortex was systematically organised and that its structure mirrored the physical properties of sound.

1940s–1950s: ELECTRICAL STIMULATION IN HUMANS

Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield, with Herbert Jasper, conducted electrical stimulation studies on awake patients during epilepsy surgery. When they stimulated the superior temporal gyrus, patients reported hearing buzzing, ringing, tones, or snippets of speech. These findings, published in Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain (1954), provided the first functional evidence that direct cortical activation of the temporal lobe could evoke auditory sensations.

1960s–1980s: HUMAN LESION AND RECORDING STUDIES

Subsequent studies confirmed Penfield’s findings. Patients with damage to Heschl’s gyrus exhibited cortical deafness — intact hearing but an inability to interpret sound. Electrophysiological recordings of auditory evoked potentials showed the earliest brain responses to sound arising from the same area, confirming its role as the primary entry point for auditory information. Neighbouring regions of the secondary auditory cortex were shown to process more complex features, such as speech rhythm, music, and melody.

1970s–1980s: ANIMAL RESEARCH AND CORTICAL PLASTICITY

In 1974, Michael Merzenich and colleagues published research in Science demonstrating cortical reorganisation in monkeys following nerve injury. Follow-up work extended these findings to the auditory cortex, showing that training or exposure to specific frequencies led to the cortical regions representing those sounds expanding. This proved that auditory maps are plastic and experience-dependent, laying the foundation for cochlear implants and modern auditory rehabilitation.

1990s–2000s: NEUROIMAGING AND FUNCTIONAL MAPPING