LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION ASSESSMENT INCLUDING ESSAY WRITING

STUDENT REVISION BOOKLET:

· MODULE: Biopsychology (A Level)

· TOPIC: Localisation of Function

· EXAM BOARD: AQA

AQA SPECIFICATION (RELEVANT SECTION)

Localisation of function in the brain and hemispheric lateralisation: motor, somatosensory, visual, auditory and language centres; Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas

LEARNING OBJECTIVES:

Recall and label brain areas responsible for key functions.

Understand typical research methods used in this area.

Evaluate the strengths and limitations of the localisation of function theory.

Apply understanding to short-answer and essay-style exam questions.

KEYWORDS FOR: LOCALISATION OF BRAIN FUNCTION

AUDITORY CORTEX: Located in the temporal lobe, it processes auditory information.

CORTEX: General term for the outer layer of the brain's regions in processing information.

CEREBRUM: The most significant part of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, is responsible for higher-order functions.

CEREBRAL CORTEX: The brain's outermost layer, responsible for higher cognitive functions.

COGNITIVE NEUROLOGIST: A specialist who studies how brain damage or neurological disorders affect cognitive functions like memory, language, and decision-making.

BRAIN LOBES: The four main lobes of the brain, each associated with specific functions:

FRONTAL LOBE: Responsible for reasoning, problem-solving, and motor control.

PARIETAL LOBE: Processes sensory information and spatial awareness.

OCCIPITAL LOBE: Primarily involved in visual processing.

TEMPORAL LOBE: Key for auditory processing and memory functions.

BROCA’S AREA: A region in the frontal lobe associated with speech production.

DISTRIBUTED PROCESSING: The concept that brain functions are not isolated but depend on networks of interconnected regions working together.

EQUIPOTENTIALITY THEORY: This theory suggests that while some essential functions may be localised, higher cognitive functions are more distributed across the brain.

HOMUNCULUS MAN: A visual representation of how different body parts are mapped onto the somatosensory and motor cortices according to the amount of control or sensory input they receive.

LOBES VS CORTICES: Lobes are the broader regions of the brain (e.g. frontal, temporal), while cortices are specialised areas within the lobes that handle specific tasks, such as the visual cortex for vision.

LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION: The theory that certain brain areas are specialised for specific functions, such as language or movement.

MOTOR CORTEX: Controls voluntary movements and is located in the frontal lobe.

NEUROIMAGING: Techniques such as fMRI and PET scans allow scientists to visualise brain activity and better understand the distribution of functions across different brain regions.

PHANTOM LIMB: The phenomenon where individuals who have had a limb amputated continue to feel sensations, including pain, in the missing limb, due to the brain’s sensory map.

PHRENOLOGY: A now-debunked theory that claimed the shape of the skull could determine personality traits and cognitive abilities by mapping bumps on the head.

POST-MORTEM: The examination of a body after death to determine the cause of death or study specific conditions, often used in brain research to examine the effects of brain damage on function.

PREFRONTAL CORTEX: The region at the front of the frontal lobe, associated with decision-making, personality, and social behaviour.

SOMATOSENSORY CORTEX: Found in the parietal lobe, it processes sensory inputs from the body, such as touch, pressure, and pain.

TOPOGRAPHICAL MAPPING: The brain organises the body's sensory and motor functions in a map-like representation, as seen in the motor and somatosensory cortices.

VISUAL CORTEX: Located in the occipital lobe, it processes visual information like shape, colour, and motion.

WERNICKE’S AREA: A region in the temporal lobe responsible for language comprehension.

TYPICAL RESEARCH METHODS USED IN LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION

Cognitive Neuropsychology – studying damaged human brains through case studies. Post-mortems (e.g., Broca’s “Tan”) and later neuroimaging (fMRI, PET) were used. Especially important for speech areas where animal comparisons are not valid.

Cognitive Neuroscience uses neuroimaging (fMRI, PET) to study healthy brains and validate earlier findings; it shows real-time activation (e.g., Dronkers, Fedorenko). Distributed networks and real-time activation are also relevant for testing modularity vs. integration.

Lesion/ablation studies are mainly animal research aimed at determining visual, motor, and sensory function (e.g., Hubel and Wiesel); they allow causal inferences but lack generalisability.

Electrical stimulation/blockers in surgery – Sometimes used during live brain surgery in conscious humans, for example, when tumours are near Broca’s area. Also used experimentally on animals (e.g. Penfield) to map motor and sensory cortices and localise other regions, e.g., the visual cortex.

BRAINSTORM LOCALISATION

Name the four lobes of the brain."

"Now, point to each of them on your own head. Let’s activate your brain about the brain."

Brainstorm as many words as you can think of that link to the topic of localisation. — key terms, areas, anything you remember.

Why are you brainstorming words for localisation?"

Because it acts as a retrieval cue — when you start listing things, it jogs other memories linked to the same schema. This helps you access things you do know but might otherwise forget.

Because it helps with essay writing — it forces you to be systematic, so you don’t leave out important AO1 or AO3 points in a 16-marker.

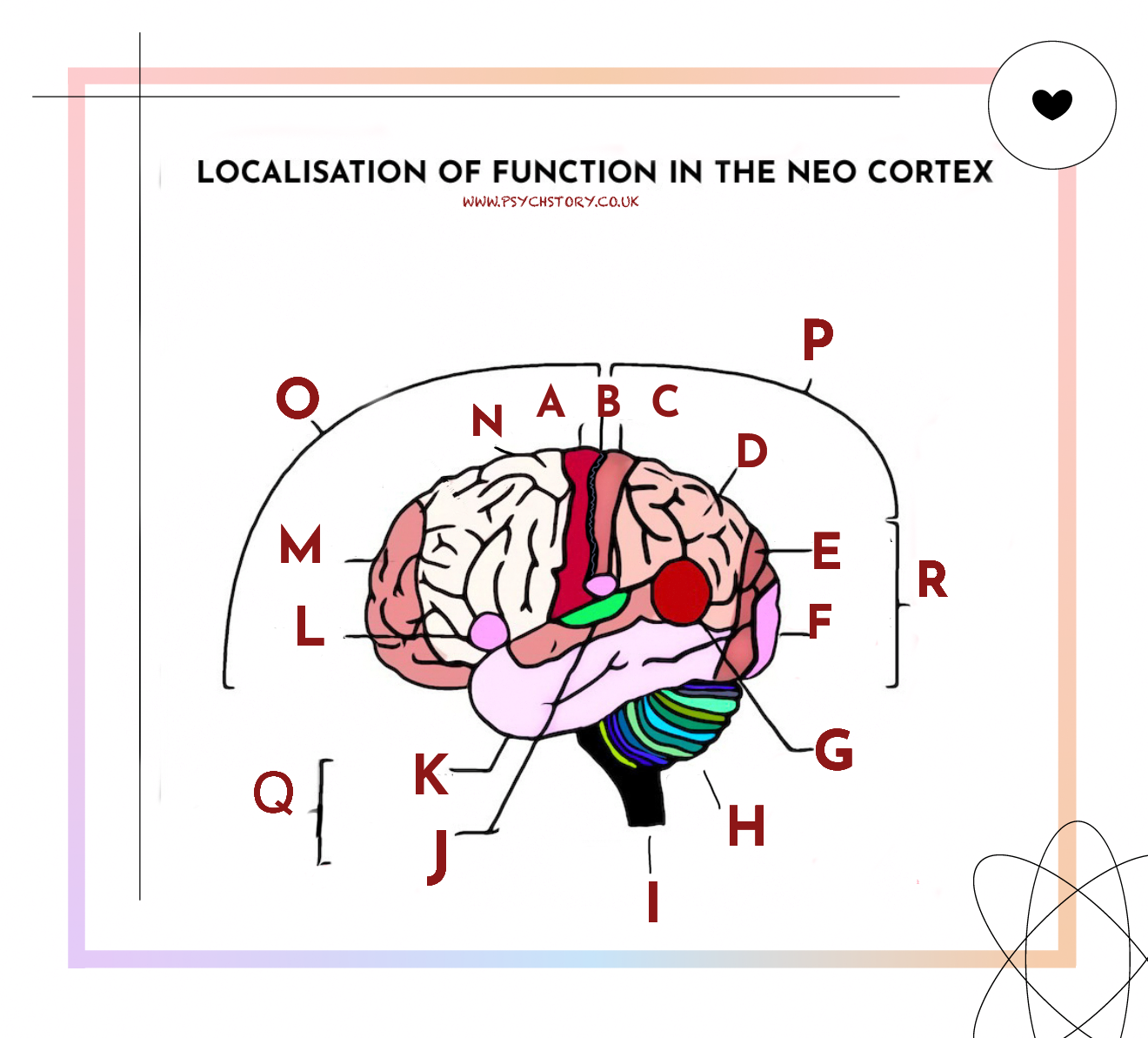

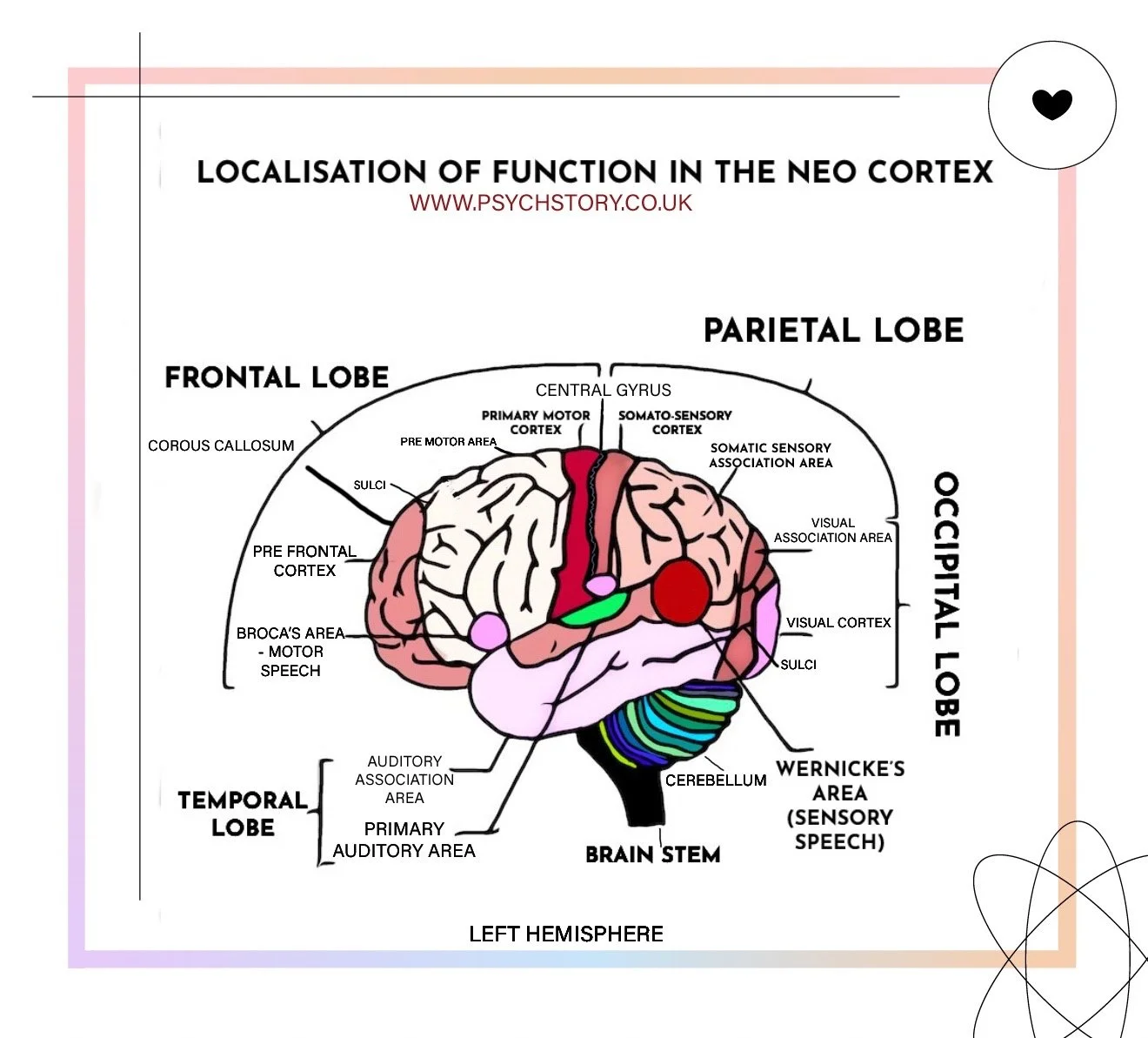

TASK ONE: LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION IN THE NEO-CORTEX

Below is a list of brain regions and their functions. Write the corresponding letter next to each name and description

1. Somatosensory Cortex

2. Cerebellum

3. Broca’s Area (Motor Speech)

4. Visual Association Area

5. Premotor Area

6. Auditory Association Area

7. Brain Stem

8. Prefrontal Cortex

9. Primary Motor Cortex

10. Visual Cortex

11. Central Gyrus

12. Somatic Sensory Association Area

13. Parietal Lobe

14. Temporal Lobe

15. Primary Auditory Area

16. Occipital Lobe

17. Frontal Lobe

18. Spinal Cord (continuation of brain stem)

TASK 6: AO2 & AO3 MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS – LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION

1. A patient loses the ability to speak after a stroke damages Broca’s area but regains speech after physiotherapy. What does this suggest about the localisation of function?

A. Broca’s area is not involved in speech after all

B. Speech is never localised and is processed across the whole brain

C. Localisation exists, but the brain can redistribute functions when damaged

D. Language recovery is due to memory compensating for lost speech pathways

2. AQA examiners report that students often overuse Phineas Gage to support localisation. Why is this a weak AO3 point?

A. He had damage to subcortical structures, not cortical ones

B. The case was misreported and discredited

C. His injury was not in any region listed on the AQA specification

D. His language was severely affected, which contradicts the theory

3. According to evolutionary theory, why do many species, including humans, show localisation of brain function?

A. Specialised modules were naturally selected because they improved the speed and efficiency of adaptive behaviours

B. Localisation evolved to prevent duplication of brain regions across hemispheres

C. Localisation became fixed because it reduced metabolic demand in neural pathways

D. Species with diffuse brain organisation were less able to respond to environmental challenges

4. fMRI activates Broca’s area and other frontal and temporal regions during a speech task. What does this suggest about how the brain functions and is organised?

A. Broca’s area only activates when the task involves writing, not speech

B. Activation in other areas likely reflects random noise in brain scans

C. Brain functions, such as speech, may be supported by broader interacting networks

D. The scanner misattributed hearing to speech output

5. Research shows that many left-handed people process language in non-typical brain areas. What issue does this raise for localisation theory?

A. Left-handers rely on the cerebellum for speech

B. Localisation may not apply in the same way to all individuals

C. Language in left-handers is processed through subcortical structures

D. Only right-handers exhibit accurate localisation.

6. In a study comparing language regions in men and women, researchers found that women have significantly larger volumes in Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. What bias might the standard localisation theory be criticised for?

A. Alpha bias – overestimating female advantage in language

B. Beta bias – assuming structural differences don’t affect function

C. Selection bias – ignoring right-hemisphere involvement

D. Measurement bias – failing to control for skull size in MRI scan

· 7. How has the theory of localisation of function contributed to real-world clinical practice?

A. It enables clinicians to link specific cognitive deficits to areas of damage, guiding targeted rehabilitation

B. It proves why some people are left-brained and others right-brained

C. It has allowed doctors to reverse language loss through hemisphere switching

D. It explains why people recover faster when brain lesions occur bilaterally

8. In a study comparing language regions in men and women, researchers found that women have significantly larger volumes in Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. What bias might the standard localisation theory be criticised for?

A. Alpha bias – exaggerating sex differences

B. Beta bias – minimising sex differences

C. Androcentrism – focusing only on male data

D. Selection bias – using only bilingual speakers?

TASK 7: AO2 APPLICATION QUESTION –

Lotta’s grandmother suffered a stroke in the left hemisphere, damaging Broca’s area and the motor cortex. Using your knowledge of the functions of Broca’s area and the motor cortex, describe the problems that Lotta’s grandmother is likely to experience. (4 marks) A02

Prompt:

What difficulties might she experience based on what these areas control?

What kind of evidence supports your answer?

How would four marks be utilised?

TASK 8 TYPICAL EXAMINATION QUESTIONS

1. Studies have identified Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas responsible for language. Outline the difference in function between Broca’s area and Wernicke’s area. (2 marks) A01.

2. Discuss what research has shown about the localisation of function in the brain. (8 marks) A01 AND A03

3. Lotta’s grandmother suffered a stroke in the left hemisphere, damaging Broca’s area and the motor cortex. Using your knowledge of the functions of Broca’s area and the motor cortex, describe the problems that Lotta’s grandmother is likely to experience. (4 marks) A02

4. Lotta worries that she will be unable to recover because of her grandmother’s age. Using your knowledge of plasticity and functional recovery of the brain after trauma, explain why Lotta might be wrong. (8 marks) A02

5. Discuss localisation of function in the brain. (16 marks) A01 and A03

ANSWERS

QUESTIONS 1-3

A – Primary Motor Cortex

B – Central Gyrus

C – Somato-sensory Cortex

D – Somatic Sensory Association Area

E – Visual Association Area

F – Visual Cortex

G – Cerebellum

H – Brain Stem

I – Spinal Cord (continuation of brain stem)

J – Primary Auditory Area

K – Auditory Association Area

L – Broca’s Area (Motor Speech)

M – Prefrontal Cortex

N – Premotor Area

O – Frontal Lobe

P – Parietal Lobe

Q – Temporal Lobe

R – Occipital Lobe

SAMPLE AO2 ANSWER (4 MARKS):

Lotta’s grandmother will likely experience difficulty producing speech due to damage to Broca’s area, which controls language production. She may also struggle with voluntary movement on the right side of her body, as the motor cortex in the left hemisphere controls the opposite side. This prediction is supported by case studies such as Broca’s patient “Tan,” who had similar speech issues, and evidence from electrical stimulation and brain imaging, which consistently links these regions to their respective functions.

What a Good AO2 Answer Should Do (4 marks):

Applies knowledge of brain areas to the specific case (Lotta’s grandmother)

Shows understanding of contralateral control and the function of Broca’s area.

Supports with appropriate evidence (e.g. case studies, scans)

It is concise, relevant, and avoids generic definitions — it applies theory to the scenario.

AO2 & AO3 MULTIPLE CHOICE ANSWERS– LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION

1) C

2. C

3. A

4. C

5. B

6. B

7. A

8. B

ESSAY WRITING

HOW TO WRITE A 6-MARK AO1 ANSWER ON LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION

STEP ONE: EXPLAIN THE ESSAY TITLE

A01 is an account, outline, or description of a theory or research (APFC: Aim, Procedure, Findings, Conclusion). You should report the essence of a theory or study using appropriate terminology. No evaluation goes here.

The cerebrum is the most significant part of the brain, and the neocortex is the ¼-inch thick outer layer of the cerebrum. It is the centre of all higher cognitive functions.

Localisation of function refers to pinpointing specific cognitive functions — such as language, voluntary movement, and sensation — within the neocortex. This theory asks whether these functions are consistently located in the same place across individuals and whether damage to a particular area results in permanent loss of that function.

STEP TWO: DESCRIBE A LOCALISED AREA

Pick 2-3 from the following list as detailed in the specification. While the specification lists five areas of localisation, you are not required to discuss all of them. Depth (focusing on 1-2 theories) is preferred over breadth (covering 3-4 theories) in the A01 section.

Motor cortex

Somatosensory cortex

Language cortices (Broca and Wernicke's areas)

Visual cortex

Auditory cortex

FOR EACH AREA, YOU NEED TO KNOW

What is the function for?

What kind of research supports this? (Post-mortem studies, scans, split-brain research, electrical stimulation in surgery, etc.)

Where is the function located in the cortex?

“DESCRIBE/OUTLINE localisation of function in the cerebral cortex

The A01 is the "describe" question, so you must outline clearly and factually. No evaluation. Structure matters.

STEP THREE: READ THE EXAMINER’S FEEDBACK.

If feedback is available, study it carefully. Examiner reports reveal exactly where students succeed and where they go wrong. The mistakes highlighted are often repeated across cohorts year after year. Understanding these common pitfalls gives you a strategic advantage and can make the difference between missing and exceeding a grade boundary.

EXAMINER FEEDBACK

✔️ High-level responses:

Students accurately described specific brain areas and their functions.

Used relevant case studies and research linked directly to localisation (not just lateralisation)

Evaluated by discussing how well the evidence supports the theory.

❌ Common mistakes:

Using Phineas Gage as evidence for localisation (his case does not map to the areas named in the spec)

Describing split-brain research without linking to localisation

Generic evaluation is not applied to localisation theory.

MODEL AO1 ANSWER (6 MARKS)

(REMEMBER

Define localisation of function.

Explain what it is – the idea that specific areas of the brain control specific functions.

Give historical background.

Mention the origin of the theory (e.g. phrenology), and contrast it with older ideas like equipotentiality, which said the brain acted as a whole.

Name and describe at least three localised brain areas.

You must say:

What each area does (its function)

Where in the brain is it located (which lobe or hemisphere)

Include hemispheric lateralisation (left and right sides) and contralateral control (left controls right, and vice versa).

Localisation of function is the theory that different brain areas are responsible for particular psychological or physiological functions. According to this view, specific regions of the cerebral cortex control specific processes such as movement, sensation, vision, hearing, or language. It is hypothesised that when a particular brain area is damaged, the function associated with it is typically lost or impaired.

The modern theory of localisation was developed in the 19th century. At the time, scientists were commissioned to test the claims of phrenology, a theory that linked skull shape to personality traits. Although phrenology was disproven, testing it revealed that damage to specific brain areas produced consistent functional losses, supporting the idea that functions may be localised.

Several areas of the cortex play distinct roles. For example, the motor cortex, located at the back of the frontal lobe, controls voluntary movement. In the parietal lobe, the somatosensory cortex processes sensory input from the skin. The visual cortex, located in the occipital lobe, processes visual information, and the auditory cortex, located in the temporal lobe, processes auditory information.

Language functions are also thought to be localised: a region in the frontal lobe is associated with speech production. In contrast, an area in the temporal lobe is linked to language comprehension.

The brain is divided into two hemispheres, and many functions are contralateral, meaning each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body. Some functions, such as language, are also lateralised, being dominant in one hemisphere.

TASK 7: HOW TO STRUCTURE AO3 FOR LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION (10 MARKS )

You are being assessed on how well you evaluate the theory. This means weighing up the strength of evidence, considering alternative explanations, and showing insight into real-world and theoretical implications.

EVALUATION OF THEORIES (A03)

STEP 1: START WITH ANALYSING RESEARCH SUPPORT

Show that your evaluation is layered. Evaluate these points in terms of:

Evidence from case studies and research supporting localisation (e.g., Broca and Wernicke’s work, fMRI scans, and electrical stimulation studies).

Criticisms of localisation, such as Karl Lashley’s equipotentiality theory, which suggests that higher cognitive functions are distributed across the brain rather than localised.

The usefulness of localisation in clinical settings (e.g., treating stroke patients), but acknowledging that distributed processing and brain plasticity may challenge strict localisation.

Discuss the methodological limitations of research methods, such as using post-mortems or animal studies, which may limit the generalisability to live human behaviour.

You could also mention split-brain research and how it has informed localisation theory, especially about hemispheric specialisation.

Instruction: Always begin with research evidence. Start with weaker or limited methods, then build to more credible support.

a. Case Studies (Weak – Individual Differences Limit Generalisability)

e.g. Broca’s patient “Tan” showed speech loss and damage to the left frontal lobe. However, it’s just one individual. His brain may have had atypical organisation, and the evidence is from a post-mortem, not live brain activity.

b. Animal Studies (Weak – Poor Generalisability)

Ablation research (e.g., Lashley) showed that some functions, like memory, are not strictly localised, especially in rats. However, applying animal research to human cognition is methodologically limited, especially for uniquely human faculties such as language.

c. Electrical Stimulation (Moderate – Controlled but Invasive)

Penfield’s neurosurgical stimulation of live patients revealed mapped motor and sensory cortices, strongly supporting localisation. But these are rare and often involve clinical populations rather than healthy brains.

d. Brain Imaging (Strongest – Live, Objective, Large Samples)

fMRI and PET scans provide the most substantial evidence: they show real-time brain activity in living humans, with consistent activation of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas during speech and comprehension tasks.

Triangulation: This shows how multiple methods (post-mortems, stimulation, scanning) converge on similar findings, strengthening the claim of localisation.

STEP 2: EVAKUATE THE THEORY ITSELF –

IDENTIFY YOUR ARGUMENTS

Identify your arguments and points.

Generalisability:

Distributed parallel functions versus localisation.

Evolutionary adaptive reason for localised areas.

Applied to the real world, e.g., knowing where brain functions are in the neocortex is helpful because …

Any issues or debates

GENERALISABILITY

Instruction: Show the limitations of strict localisation. Use individual differences.Generalisability: Left-handers, non-typical Brains Gender, Accidents/ Plasticity

Left-handers: ~40% of left-handers show non-typical language lateralisation. Some use the right hemisphere, or even both. This means localisation patterns vary.

Gender Differences: Studies (e.g. Pearlson) found larger language areas in women, suggesting sex differences in localisation. Most early research used male brains, potentially introducing beta bias.

Brain Damage Recovery: After strokes, language function can return as other brain areas compensate, demonstrating functional plasticity rather than rigid localisation.

Applied to the real world, e.g., knowing where brain functions are in the neocortex is helpful because …

STEP 3: EVAVUATE THE THEORY ITSELF – LOCALISATION ISN’T 100% UNIVERSAL

THEORETICAL CHALLENGE – DISTRIBUTED PROCESSING VERSUS LOCALISATION

Instruction: Now, show that some behaviours require multiple areas to work together.

Fedorenko (2012) found that Broca’s area is activated during language and non-verbal problem-solving.

Cognitive functions such as language and memory often involve networks rather than isolated centres.

The distributed functioning model argues that the brain is modular, but modules interact — localisation is real, but not absolute.

STEP 4: WHY WOULD THE BRAIN BE ORGANISED THIS WAY?

Instruction: Briefly justify why localisation makes evolutionary sense.

From an evolutionary perspective, having specialised modules would increase efficiency.

For example, language areas likely developed due to group hunting, social bonding, or coordination.

Localisation enables faster, more reliable processing of critical tasks (e.g., vision, movement, language).

STEP 5: REAL-WORLD APPLICATION

Instruction: Show how the theory is helpful beyond academia.

In neurosurgery, surgeons avoid damaging localised areas during tumour removal.

Understanding which areas control which functions in stroke rehab helps design targeted therapies.

In neuropsychology, identifying which region is damaged helps explain cognitive deficits, supporting clinical diagnosis and treatment.

STEP 6: CONCLUDE – SYNTHESISE

Instruction: Tie together both sides.

Overall, converging evidence from case studies, scanning, and surgical mapping strongly supports the theory of localisation of function. However, it must be understood as a general rule rather than a fixed blueprint. The brain shows individual differences, plasticity, and inter-regional cooperation. The best current view is that some functions are localised, but most involve interactive networks.

HOW TO AVOID SHOPPING LIST POINTS

For each of these examples, you must avoid just stating a general critique without:

Explaining it fully (what does it mean?),

Applying it to the specific study or theory being discussed,

Evaluating its impact on the findings or conclusions of the research, and

Linking it back to the question to show how it strengthens or weakens the argument.

By developing your points through point-evidence-explain-evaluate (PEEE) or similar frameworks, you will show deeper understanding and avoid the trap of making unconnected, hit-and-miss claims.

IDENTIFY THE PEEL POINTS BELOW:

The problems with using methods such as ablations and post-mortems is that participants such as Paul Leborgne aka “Tan” may have individual differences in brain organisation, for example “Tan” may have a larger speech area than other people, especially if the person was bilingual for instance. It may therefore not be possible to generalise Tan's findings to others. Moreover, post-mortems do not show real-time activity in the brain as the person is dead. Similarly, ablations are not a precise research tool; cuts may have different consequences on different brain organisations. However, since this time, much more advanced methods of investigating the brain have been introduced, for example, electrical stimulation. This method is more precise, as it can pinpoint finer details, such as topographical maps in the motor and sensory cortices. However, as animals are its main targets, it’s also difficult to generalise as animals have different motor systems, e.g., tails. Lastly, the introduction of scans is the most robust evidence of localisation because …. Scans can use human participants, 1000s of participants can be recruited, it’s not invasive, scans look at real-time brain activity (not dead brains)

This means that researchers can confidently assume most people have functions organised or localised in the same places.

FULL ESSAY: DISCUSS LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION IN THE NEOCORTEX/BRAIN

MARKS = 16 Marks

A01 = 6 (Outline and description)

A03 = 10 (Evaluate)

SPECIFICATION SAYS:

Localisation of function in the brain: motor, somatosensory, visual, auditory and language centres; Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas.

COMMAND WORDS:

"Discuss" = A01 & A03, i.e., outline and evaluate

A01: DESCRIPTION OF THEORY

The cerebrum is the most significant part of the brain, and its outer layer, the neocortex, is approximately ¼-inch thick. This layer is responsible for all higher intellectual abilities in mammals, such as reasoning, language, and decision-making. The theory of localisation of function refers to the identification and mapping of higher cognitive functions—such as language, voluntary movement, and physical sensation—to specific regions of the cerebral cortex. It also examines whether these functions are consistently located in the same brain areas across individuals and how damage to these areas might affect functioning.

One key area that has been localised is language. In the 1800s, Paul Broca discovered a region of the brain responsible for speech production. He made this finding through a post-mortem on a patient nicknamed "Tan," who had lost the ability to speak except for that one word. Broca found damage to the left frontal lobe of the neocortex, later called Broca’s area, linking this region to speech production.

Similarly, Carl Wernicke identified a region of the brain responsible for language comprehension. This area, located in the left temporal lobe, was discovered through post-mortem examinations of patients who were unable to understand spoken language. The area, now known as Wernicke’s area, is critical for understanding language.

Other functions, such as sensory and motor control, have also been localised. The somatosensory (SS) cortex, situated along the front strip of the parietal lobe, processes sensory and tactile information. It is organised topographically, meaning each part of the body corresponds to a specific location on the cortex, with the left hemisphere controlling the right side of the body and vice versa.

The motor cortex lies adjacent to the somatosensory cortex along the back strip of the frontal lobe and is responsible for voluntary movement. This area has been studied using electrical stimulation, which replicates brain signals, and ablation, in which portions of the cortex are surgically removed to observe the effects. Like the somatosensory cortex, the motor cortex is systematically arranged, with more space devoted to body parts that require fine motor control, such as the hands and face.

EVALUATING LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION

SUMMING UP THE RESEARCH ON LOCALISATION OF FUNCTION

One limitation of research into the localisation of brain function is its reliance on case studies, ablations, and post-mortem examinations. Case studies, such as the famous example of Paul Leborgne, also known as "Tan", highlight individual differences in brain organisation. For example, "Tan" may have had a larger speech area than other individuals, particularly if he had been bilingual before his injury. This makes it challenging to generalise findings from one person to the broader population. Moreover, post-mortem studies only show brain structure after death and do not provide insights into real-time brain activity, limiting the applicability of their findings. Similarly, ablations (surgical removal of brain tissue) are imprecise, as their effects may vary depending on individual brain organisation or even across different species, reducing the validity of these methods for studying human brains.

On the other hand, since the 19th century, more advanced techniques have been developed, such as electrical stimulation, which allows researchers to map smaller brain regions in more detail. This method can identify topographical maps in the motor and sensory cortices. However, animal studies using these methods face challenges in generalising findings to humans, as animals have different motor and sensory systems (e.g., tails, whiskers) that do not directly translate to human experiences.

In contrast, since the 1990s, neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI and PET scans have offered robust support for the localisation of function in the neocortex. These techniques can involve thousands of participants and are non-invasive, enabling real-time observation of brain activity. Additionally, case studies of patients with damage to Broca’s or Wernicke’s areas consistently show that these regions are crucial for language production and comprehension. For example, Broca’s aphasia, caused by damage to Broca’s area, leads to an impaired ability to produce language. In contrast, Wernicke’s aphasia, caused by damage to Wernicke’s area, results in difficulties with language perception. The consistency of these findings supports the theory that brain functions are typically organised in the same areas for most people.

LEFT-HANDERS

A significant challenge to the theory of functional localisation is that not all individuals have the same brain organisation. For example, around 40% of left-handers have brain functions that are organised differently, with Broca’s area (responsible for speech production) located in the right hemisphere instead of the left, and the visual-spatial processing area situated in the left hemisphere. Furthermore, even among the 60-70% of left-handers who use the left hemisphere for language, their brains are wired differently from right-handers because they must integrate information across both hemispheres more extensively. Additionally, a small proportion of left-handers have a bilateral language organisation, where both hemispheres are involved in language processing. This variation in brain organisation means that the theory of localisation, which assumes functions are always tied to specific regions, does not apply uniformly to left-handers and, in some cases, even to right-handers.

NON-TYPICAL BRAINS

Similarly, individuals who are congenitally blind or deaf may develop different brain organisation, particularly in the auditory and visual cortices. For these individuals, the areas of the brain that would typically process auditory or visual information may be "pruned" (shrunk or reorganised) due to a lack of stimulation. Instead, these regions may be recruited to support other intact senses, such as touch for blind individuals or vision for deaf individuals. This demonstrates how localisation of function can vary significantly depending on sensory experience.

MALE VERSUS FEMALE BRAINS

There is also evidence that male and female brains differ in brain structures involved in language processing. For example, research by Pearlson et al. has shown that two language-related areas in the frontal and temporal lobes are significantly larger in women. In their study, MRI scans of 17 women and 43 men revealed that Broca's area was 23% larger in women, and Wernicke's area was 13% larger. These findings were later supported by additional research from the University of Sydney, which reported that Wernicke’s area was 18% larger in women, and Broca’s area was 20% larger than in men. Additional studies have suggested that the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres, is generally larger in women, though this finding is debated. These anatomical differences indicate that localisation-of-function theories may not be universally applicable across genders. In fact, they may exhibit beta bias, as they often ignore structural differences between male and female brains and fail to account for variations in cortical activation during language tasks.

PLASTICITY

Another factor that challenges the theory of localisation is the brain’s ability to adapt, known as functional plasticity. This refers to the brain's capacity to reassign functions from damaged areas to other undamaged regions. For example, if a person sustains damage to their language centre in the left hemisphere, the right hemisphere or other adjacent areas can take over language processing functions. This capacity for reorganisation casts doubt on the idea that cognitive functions are strictly localised in specific brain regions, as other parts of the brain can compensate for damaged areas.

ALTERNATIVE THEORIES

The theory that functions are strictly localised to particular brain areas has been questioned by some psychologists. Karl Lashley, for example, proposed the equipotentiality theory, which argues that while basic motor and sensory functions may be localised, higher mental functions are not. Lashley’s work showed that when one part of the brain is damaged, other areas can often compensate for the lost function, suggesting a more flexible brain organisation.

Wernicke also argued that although different areas of the brain are specialised, they must communicate with one another to produce complex behaviours. One example is a man who lost the ability to read after sustaining damage to the connection between his visual cortex and Wernicke’s area. This suggests that connections between brain regions are crucial for complex tasks such as language. That damage to these pathways can lead to impairments that mimic those of localised brain regions.

This perspective aligns with the distributed processing model, which emphasises that brain functions are not confined to single regions but depend on interactions among multiple brain areas. Critics of strict localisation argue that the brain’s interconnectedness means that understanding how different regions communicate is just as important as identifying where functions are localised.

REASONS FOR EVOLUTIONARY ADAPTATION

From an evolutionary perspective, localisation of function makes sense, as the neocortex likely evolved in response to environmental selection pressures. Factors such as climate, diet, food availability, group size, and social interactions likely shaped the brain's development. For example, the development of language may have been driven by the need for group hunting. Humans, lacking physical advantages like speed or sharp teeth, relied on cooperative hunting and communication to survive. This need for complex communication likely led to the evolution of specialised brain regions such as Broca’s area. Evolutionary psychologists argue that natural selection favoured the development of these specialised areas to enhance group coordination, problem-solving, and social bonding, thereby improving survival and reproductive success.

APPLICATION TO THE REAL WORLD

The theory of localisation of function has critical real-world applications, particularly in psychiatry. For example, future developments in "modular psychiatry" may rely on a modular understanding of the brain. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, which allow for detailed brain mapping, could enable more accurate diagnoses of mental and emotional disorders. Schizophrenia, for instance, has been linked to problems with Broca’s area, demonstrating how understanding brain regions can aid in diagnosing and treating cognitive disorders.

CRITICISMS

Despite the historical importance of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas, more recent research has challenged the strict localisation of these functions. Dronkers et al. (2007) conducted an MRI scan on Tan’s brain to confirm Broca’s findings. Although they found a lesion in Broca’s area, they also found evidence that other brain areas may have contributed to Tan’s speech production difficulties. Furthermore, research by Fedorenko (2012) has shown that Broca’s area is active during cognitive tasks unrelated to language. She discovered that Broca’s area has two distinct regions: one involved in language, and the other in demanding cognitive tasks, such as solving mathematical problems. This suggests that Broca’s area may not be solely responsible for speech production, and deficits in Broca’s aphasia could be due to damage in neighbouring brain regions.

A SHORT EXAMPLE OF OTHER POSSIBLE WAYS TO WRITE A01 and A03.

Instead of separating A01 and A03, you can intersperse them throughout the explanation. For example:

A01 general theory of localisation descriptor:

Localisation of function refers to the concept that specific functions, such as language and memory, are localised in some regions of the brain. EXAMPLE: MOTOR CORTEX One key area believed to be localised is voluntary movement. As early as the 1700s, physiologists began identifying what would later be known as the motor cortex through a method called ablation, where cortical tissue was removed from animals to observe the effects. For instance, when researchers ablated the back strip of the frontal lobe, they consistently observed a loss of motor function in the animals, suggesting that this region was responsible for movement.

A03: However, the use of ablation has limitations. It is invasive and often conducted on animals, making it difficult to generalise findings to humans. Further research refined the technique by removing smaller areas of the brain, enabling scientists to map how the cortex represented the body, leading to the discovery of the topographical map. This map shows that areas such as the fingers and tongue, which require greater dexterity, have more cortical tissue devoted to them. This mapping of the motor cortex provides strong evidence for localisation.

A03: More precise methods, such as electrical stimulation, have since been used in human patients, particularly during neurosurgery. For example, when removing tumours, surgeons stimulate the brain to identify essential areas, such as the somatosensory cortex, to avoid damaging them. Research using this method has shown that stimulating the anterior part of the parietal lobe can cause patients to feel sensations in different parts of their bodies, further demonstrating the localisation of tactile processing.

A03: Moreover, phantom limb syndrome in amputees offers additional evidence for the somatosensory cortex. Even after the loss of a limb, patients still feel sensations in the missing limb because the brain continues to represent the limb in the topographical map. This ongoing representation supports the idea that the somatosensory cortex is localised, as it continues to function even when the physical limb is absent.

This approach allows for the explanation of key terms (A01) and the inclusion of research and evaluation (A03) in a more integrated way.

FURTHER READING

"The Cognitive Neurosciences" (5th edition) – Gazzaniga, M.S. (2019)

Comprehensive exploration of brain function, including localisation, distributed processing, and neuroplasticity.

"Principles of Neural Science" (6th edition) – Kandel, E.R., Schwartz, J.H., Jessell, T.M., Siegelbaum, S.A., & Hudspeth, A.J. (2021)

A detailed examination of neural pathways and brain organisation, covering recent findings on brain function and localisation.

"Human Brain Function" (2nd edition) – Frackowiak, R.S.J. et al. (2004)

Offers insights into neuroimaging studies supporting localisation and distributed networks.

"Plasticity in the Human Brain: The Human Brain's Capacity for Change" – Pascual-Leone, A. (2005)

Focuses on neuroplasticity and how the brain reorganises itself after injury or learning new tasks.

"Neuroscience: Exploring the Brain" (5th edition) – Bear, M.F., Connors, B.W., & Paradiso, M.A. (2020)

An accessible text that covers localisation of function with an emphasis on recent research findings.

ONLINE RESOURCES

Society for Neuroscience (SfN): https://www.sfn.org/

Offers a variety of resources on brain localisation, neuroplasticity, and cognitive neuroscience.

BrainFacts.org: https://www.brainfacts.org/

Educational content focused on brain function, localisation, and plasticity.

PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Database of research articles on localisation, neuroplasticity, and distributed processing.