HEMISPHERIC BRAIN LATERALISATION

SPECIFICATION: Hemispheric lateralisation: visual, auditory and language centres; Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas

INTO THE SILENT LAND

Neuroscientist Paul Broks opens Into the Silent Land: Travels in Neuropsychology (2003) with two contrasting case studies that show how damage to different sides of the frontal lobes leads to very different emotional and behavioural outcomes. This provides a clear real-world illustration of functional lateralisation, showing that the left and right hemispheres are specialised for different aspects of emotional control and social behaviour.

Michael and Stuart have sustained near symmetrical injuries to the frontal cortex, but on opposite sides of the brain. Michael’s injury involves the right frontal lobe, while Stuart’s injury involves the left frontal lobe. Because the injuries are comparable in location and severity but differ only in laterality, the cases provide insight into hemispheric function.

The contrasting behavioural outcomes demonstrate that the two hemispheres of the frontal lobe are not functionally identical. Right frontal lobe damage in Michael is associated with emotional excess, disinhibition, and heightened affective empathy. In contrast, left frontal lobe damage in Stuart is associated with emotional blunting, reduced motivation, and affective indifference.

Despite the broad preservation of intelligence and language, each individual’s emotional life and social behaviour are altered in opposite directions.

These paired case studies are therefore used to illustrate:

Lateralisation of frontal lobe function

Differences between right and left hemisphere contributions to emotion

How similar brain injuries can produce opposite psychological outcomes

Why emotional regulation and social behaviour are neurologically organised rather than unitary

By presenting mirror-image injuries with mirror-image consequences, Broks’ chapter provides a compelling demonstration that which side of the brain is damaged matters, not only how much damage has occurred.

CHAPTER ONE: DIFFERENT LIVES

MICHAEL

‘Why does raw meat give me a hard-on?’

This is Michael, chopping sirloin ready for the stir-fry. Typically, he prepares a good lunch: beef in hoisin sauce. He’s bought some beer, too. We’re drinking straight from the can. Amy, his girlfriend, sits at the kitchen table reading a magazine.

‘Michael,’ she says, without looking up.

Michael slides the diced beef into the wok, where it sizzles in the hot oil.

‘Easy, Amy. Only a twitch.’ He winks at me, then drops what he is doing and strides out of the room. ‘Have a listen to this,’ he calls over his shoulder, and soon the place is awash with cascades of sound – brittle arpeggios, tumbling fragments of melody. It is very loud.

Michael returns, fingertips to temples, head tilted back.

‘Koto,’ he says. ‘Japanese. Astonishing.’

From this angle, the dent in his head, about three inches up from the right eyebrow, is more noticeable.

Michael had climbed a tree to retrieve an entangled kite. He needn’t have bothered because the wind gusted and the kite drifted down of its own accord, but he was high up by then. He was calling something to Amy, but she couldn’t make it out. Her dreams recall how abruptly his voice was stifled by the creak and crack of a branch, and the wind-whipped silence of the free fall as his body cleared the boughs. Concealed within thick tufts of meadow grass was a spur of rock. Amy’s dreams also record the crack of her head hitting the stone. That’s what wakes her.

The fall fractured Michael’s skull and released a flash flood of bleeding into the right frontal lobe. ‘I thought his number was up,’ the surgeon told me, and had said as much to Amy as she kept vigil over Michael’s comatose body. ‘No point beating about the bush,’ said the doctor. But, after three days and nights, Michael came back to life — with a different number.

Michae has trouble being emotional. Amy has to rein him in. He’ll talk to strangers in the street, he’ll tell them they’re beautiful, or their children are, or their pets. He wants to touch. He wants to celebrate. Beggars bring a tear to his eye. He once gave a man his coat and a £10 note. People take advantage.

Michael’s empathic response is hair-triggered, but more complex social calculations befuddle him. When he first came home from the rehab centre, his tastes were plain. Amy said he lived on fish fingers and Led Zeppelin. Michael said it was like going back in time. He’d always liked these things, and now he didn’t feel he should pretend otherwise. Fine, said Amy. But she would not tolerate the porn videos. Like Stuart, Michael no longer feels the need to dissimulate.

Michael saw me off at the front door. He was close to tears. He pulled me to him and kissed me on the cheek. For an instant, I thought he was going to say he loved me.

INJURIES SUSTAINED

Nature of injury

Traumatic brain injury caused by a fall from a tree.

Skull fracture.

Intracranial haemorrhage with bleeding into the right frontal lobe.

Visible depression dent approximately three inches above the right eyebrow, consistent with focal frontal impact.

Mechanism

Fell from a height.

Head struck a spur of rock concealed in the grass.

Resulted in direct blunt force trauma to the right frontal cortex.

Functional consequences (linked to injury site)

Hyper-emotionality and disinhibition.

Excessive empathy and emotional reactivity.

Reduced social judgment and poor regulation of impulses.

Increased emotional expression (crying, generosity, tactile behaviour).

Reduced ability to mask or regulate socially inappropriate behaviour.

Loss of dissimulation.

Neuroanatomical implication

Damage to the right frontal lobe, particularly regions involved in:

Emotional regulation

Social inhibition

Behavioural restraint

Pattern consistent with acquired frontal disinhibition syndrome.

STUART

The next day, I’m over at Stuart’s. We sit in his stuffy front room. An ornate black clock (his early-retirement present) clings to the wall like a huge fly. As I struggle with milky tea, Stuart locks me in his gaze. He is about to say something, but doesn’t. It is a long pause. Eventually, he speaks.

‘I don’t love you any more, do I, love?’

The words are intended for his wife, Helen, who sits beside him.

‘No, love,’ she replies. ‘So you say.’

There is silence again, except for the tick of the insectoid clock. The dent in Stuart’s head is above the left eyebrow.

Stuart’s twist of fate was a motorway pile-up. A bolt snapped and blasted like a bullet from the vehicle in front. It came through the windscreen, through his forehead and tore deep into the left frontal lobe.

Despite the immediate displacement of some brain matter, loss of consciousness was brief, as is sometimes the case with penetrating missile wounds. He told the paramedics he was fine and had better get home now, but they saw the brain stuff gelling his hair and put him in the ambulance. Soon, the surgeons were working to extract the foreign body from the interior of Stuart’s head, a process that also meant disposing of some adjacent brain tissue. Part of Stuart went with it.

In this way, Providence has created mirror-image lesions in the brain. As a neuropsychologist, my role is to compare the consequences. Stuart now has trouble getting started. Helen helps him out of bed in the morning, points him toward the bathroom, has his clothes ready, and gets him breakfast before he goes to work. She leaves him lists of things to do around the house, and magazines and puzzle books to fill the hours. But when she returns, she often finds him where she left him, sitting in silence. She’ll go over and hug him, and he’ll return the embrace, but it’s perfunctory.

He doesn’t love her any more. It’s the plain truth, and she accepts it. Stuart is not to blame. What he feels towards Helen is what he feels towards all other people, including himself: indifference. This absence of emotion frees him to tell the truth: ‘Helen, I don’t love you any more.’

Stuart can read people’s moods and motivations, but lacks the emotional charge of empathy. I ask what he feels about the little girl who was abducted and murdered last year. He knows it was a dreadful thing to happen. They should hang the murderer or chop his balls off, but no, it doesn’t make him feel anything very much. Then, he says, it’s funny, but he never used to believe in capital punishment.

‘How do you feel in yourself, Stuart?’ I ask.

‘All right.’

‘Are you miserable?’

‘No.’

‘Are you happy?’

‘I don’t think so.’ He turns to Helen. ‘Am I happy?’

Helen looks at me. I look at Stuart. The question goes in circles.

INJURIES SUSTAINED

Nature of injury

Penetrating traumatic brain injury.

A foreign metallic object entered the skull.

Injury to the left frontal lobe.

Loss of brain tissue due to surgical removal of damaged areas.

Visible dent above the left eyebrow, marking entry trajectory.

Mechanism

Motorway pile-up.

A bolt became a high-velocity projectile.

Entered through the windscreen, penetrated the forehead, and lodged in the left frontal cortex.

Functional consequences (linked to injury site)

Emotional blunting and affective flattening.

Profound loss of emotional attachment, including romantic love.

Reduced initiation (abulia).

Indifference to self and others.

Preserved cognitive understanding of events without emotional response.

Preserved theory of mind but loss of affective empathy.

Honest but emotionally detached moral reasoning.

Neuroanatomical implication

Damage to the left frontal lobe, particularly regions associated with:

Motivation and initiation

Emotional valuation

Goal-directed behaviour

Pattern consistent with acquired apathy and affective indifference following frontal lobe damage.

Into the Silent Land: Travels in Neuropsychology By Paul Broks (2003) Atlantic Books ISBN: 978 1841152299

BRAIN TERMINOLOGY RELATED TO LATERALISATION

LATERAL AND MEDIAL

Lateral (from Latin lateralis, meaning “to the side”) refers to the sides of an animal, as in “left lateral” and “right lateral”. The term medial (from Latin medius, meaning “middle”) refers to structures near the centre of an organism, the median plane. For example, in a fish, the gills are medial to the operculum but lateral to the heart.CONTRALATERAL

(from Latin contra, meaning “against”): on the side opposite to another structure. For example, the left arm is contralateral to the right arm, or the right leg.IPSILATERAL

(from Latin ipse, meaning “same”): on the same side as another structure. For example, the left arm is ipsilateral to the left leg.BILATERAL

(from Latin bi, meaning “two”): on both sides of the body. For example, bilateral orchiectomy (removal of testes on both sides of the body’s axis) is surgical castration.UNILATERAL

(from Latin uni, meaning “one”): on one side of the body. For example, unilateral paresis is hemiparesis.CORPUS CALLOSUM

A massive bundle of nerve fibres (axons) which connects the two cerebral hemispheres. There are over 200 million axons, as many as ten times more than in the spinal cord.COMMISSUROTOMY

Surgically cutting nerve fibre tracts which connect the two hemispheres

CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES AND LATERALISATION OF FUNCTION

The human brain is split into two hemispheres, left and right. Research continues into how certain mental functions tend to rely more heavily on one hemisphere than the other, a phenomenon known as lateralisation.

Lateralisation of brain function, also called hemispheric dominance or hemispheric lateralisation, is the tendency for particular neural operations or cognitive processes to be more strongly associated with one side of the brain than the other. The median longitudinal fissure divides the brain into two cerebral hemispheres, which are linked by the corpus callosum. Although the two hemispheres share many features, they exhibit asymmetries in structure and in the organisation of neural networks, and these differences are associated with specialised functions.

Lateralisation has been investigated in neurologically typical individuals and in patients with split-brain. Even so, broad claims about hemispheric dominance have many exceptions, and patterns differ from person to person because brain development varies across individuals. Lateralisation is not the same as specialisation. Lateralisation refers to how a function of a structure is divided across the two hemispheres. Specialisation is generally easier to identify as a population-level pattern because it has a more extended history in anthropology and the sciences.

A commonly cited example of lateralisation is the typical placement of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas in the left hemisphere in most people. However, claims that language functions such as semantics, intonation, accentuation, and prosody are primarily localised to one hemisphere have been challenged, with evidence suggesting contributions from both hemispheres. Another important pattern is that each hemisphere typically represents one side of the body. In the cerebellum, representation is ipsilateral, whereas in the forebrain, it is mainly contralateral.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

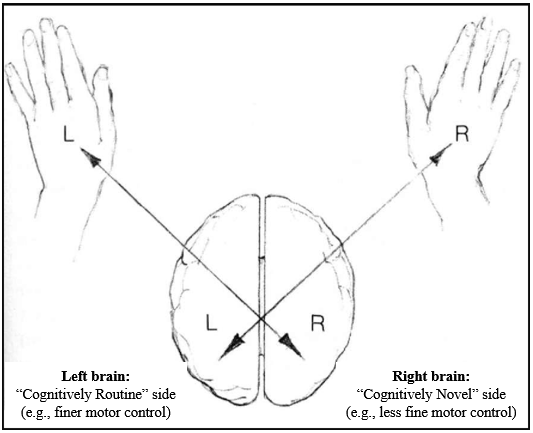

CONTRALATERAL ORGANISATION, HANDEDNESS AND HEMISPHERIC DOMINANCE

The human brain is organised contralaterally, meaning that each cerebral hemisphere primarily controls movement and processes sensory information from the opposite side of the body and sensory space. In most people, the left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and receives information mainly from the right visual field and right ear. In contrast, the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body and receives information mainly from the left visual field and left ear. This contralateral organisation applies to motor control and to major sensory systems, including vision and hearing.

Accordingly, handedness is not a superficial preference. The fact that most people are right-handed reflects that, in most individuals, the left hemisphere controls fine motor output and is also dominant for language. This means that, for most right-handed people, language processing and motor output for tasks such as speaking or writing are primarily processed in the left hemisphere. This alignment is neurologically efficient because it minimises the need for information to cross between hemispheres.

Contralateral organisation also applies to sensory input. In vision, information from the right visual hemifield of both eyes is processed by the left hemisphere, whereas the right hemisphere processes information from the left visual hemifield. In hearing, although both ears project to both hemispheres, auditory pathways are predominantly contralateral, such that sounds entering the right ear are processed mainly by the left hemisphere, and sounds entering the left ear are processed mainly by the right hemisphere. This organisation underlies the use of dichotic listening tasks to assess hemispheric dominance for auditory and language processing.

Importantly, lateralisation does not develop as a single global switch. Different systems lateralise independently; as a result, individuals may exhibit cross-dominance, such as being right-handed but left-eyed, left-handed but right-footed, or having mismatched motor and sensory dominance. This variability reflects normal developmental variation, not abnormality. Sensory dominance can also be shaped by experience or constraint, for example, when one sensory channel is consistently relied upon more than another.

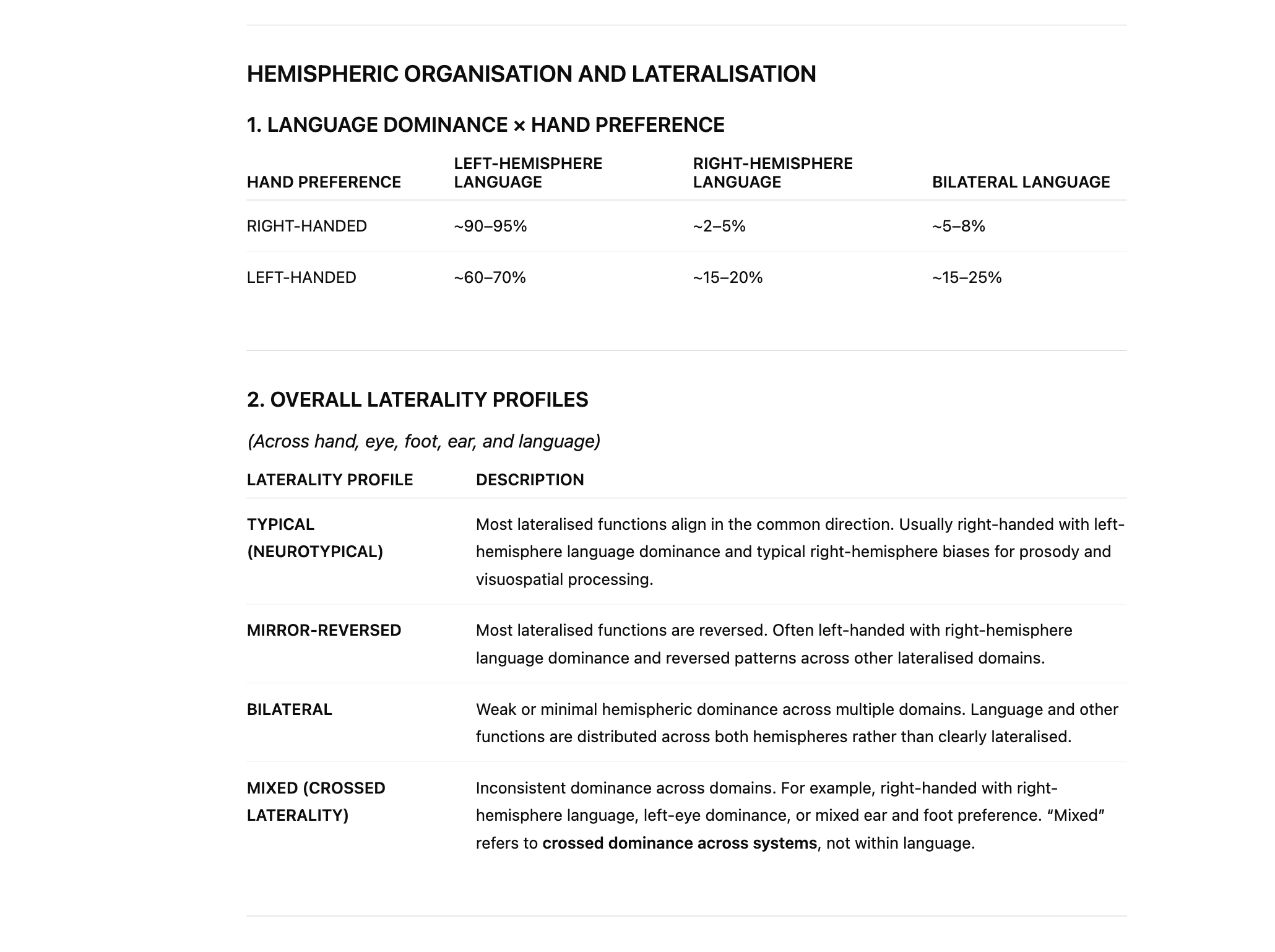

Because of contralateral organisation, handedness is closely related to—but does not rigidly determine—hemispheric dominance for language. In most right-handed individuals, language is left-hemisphere dominant. The same is true for a substantial proportion of left-handed individuals; however, overall brain organisation is more variable in left-handers. Some left- and right-handed individuals show a mirror-reversed pattern, with language-dominant processing in the right hemisphere and visuospatial processing in the left hemisphere. In this arrangement, language processing and motor control of the dominant hand remain aligned within the same hemisphere, and no additional interhemispheric transfer is required.

However, the most common pattern in left-handers is not mirror reversal. Around 60–70% of left-handed individuals still show left-hemisphere language dominance, as in right-handers. In these individuals, language is processed in the left hemisphere, while the right hemisphere governs control of the left hand. As a result, language-related information must cross the corpus callosum more frequently to guide motor output. This increased reliance on interhemispheric transfer is what is meant by "double wiring" here. Language processing occurs in one hemisphere, whereas motor execution occurs in the other, necessitating additional interhemispheric communication.

This arrangement functions well for most everyday activities. Still, it places greater demands on interhemispheric communication, particularly for tasks requiring rapid and precise symbol manipulation, such as reading, spelling, writing and arithmetic. This helps explain why language- and number-based learning difficulties, such as dyslexia and dyscalculia, are more prevalent in populations with atypical or less efficient hemispheric alignment. This relationship is probabilistic rather than causal: most left-handed individuals do not have dyslexia or dyscalculia, and most individuals with these difficulties are right-handed. The increased vulnerability reflects wiring efficiency and developmental load, not brain damage.

Some individuals exhibit bilateral organisation of functions, such as language, meaning that both hemispheres contribute substantially rather than one hemisphere being clearly dominant. This pattern is more common in left-handers but also occurs in a minority of right-handers. Bilateral organisation can sometimes confer resilience following brain injury, but it may also reduce the efficiency associated with strong hemispheric specialisation.

Older claims that left-handedness reflects brain damage are incorrect and outdated. These ideas arose from early observations of individuals who developed atypical lateralisation following early brain injury and were wrongly generalised. Modern evidence shows that left-handedness reflects normal variation in developmental wiring, not pathology. Mirror twins provide further evidence for this, demonstrating that left–right asymmetries, including handedness and language dominance, can be developmentally reversed without impairment.

Popular culture often exaggerates bilateral organisation. The character in Rain Man was based on Kim Peek, an autistic savant who lacked a corpus callosum and showed unusually independent hemispheric processing. Peek’s abilities reflected an extreme and rare neurological condition and should not be taken as representative of autism, left-handedness or bilateral language organisation more generally. His case, however, illustrates how reduced hemispheric integration can produce both striking strengths and significant limitations.

Current large-scale research indicates that left-handedness is more common than once thought, but estimates vary depending on how handedness is defined. Using strict definitions of consistent left-hand dominance, around 10–11% of the population is left-handed. When broader definitions that include mixed or task-dependent handedness are used, the prevalence rises to 15–18%, with some recent Western cohorts approaching 20%. Left-handedness is slightly more common in males, and true ambidexterity remains rare, typically occurring in fewer than 1%.

In summary, contralateral organisation explains why handedness matters, why most people show left-hemisphere language dominance, and why left-handedness is associated with greater variability in hemispheric organisation. In particular, patterns involving double wiring increase reliance on interhemispheric transfer, helping to explain both the strengths and vulnerabilities observed across individuals, including increased susceptibility to dyslexia and dyscalculia in some developmental trajectories

LATERALISED FUNCTIONS

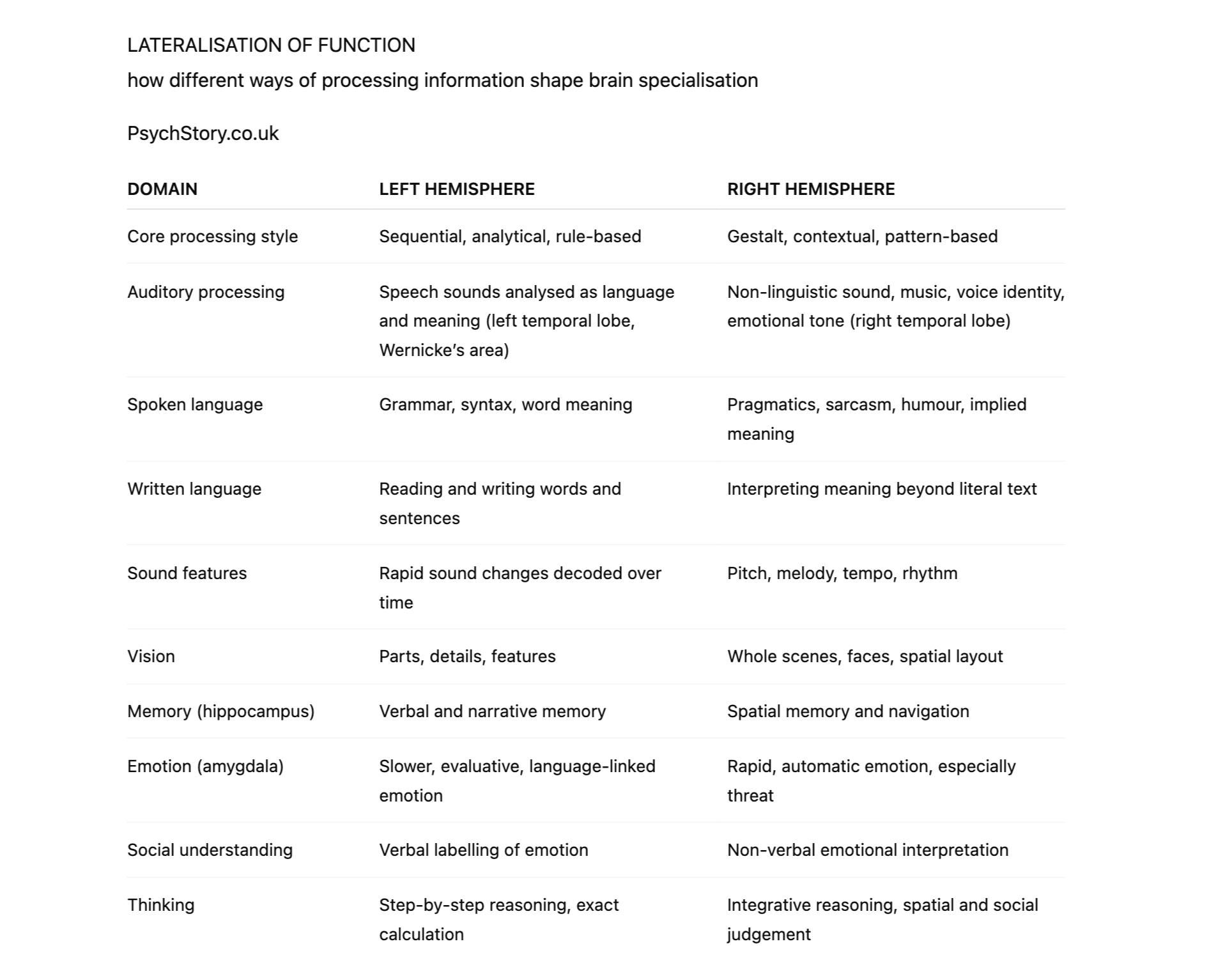

Lateralisation of function does not mean that one hemisphere performs a task and the other does not. Both hemispheres are active in almost all complex behaviour. What differs is the mode of processing each hemisphere tends to bring to that behaviour. This difference in processing style is what produces consistent patterns of lateralisation across language, emotion, memory, music, and perception.

The left hemisphere is biased towards processing information sequentially, analytically, and symbolically. It is particularly suited to handling information that unfolds over time and depends on order, rules, and discrete units. Speech is a clear example. Spoken language consists of rapidly changing sounds that must be processed in the correct temporal sequence for meaning to be recovered. Damage to the left superior temporal lobe, particularly Wernicke’s area, disrupts the ability to understand speech as language, even though hearing itself remains intact. The sounds are heard, but they are no longer organised into meaningful words and sentences. This is why left hemisphere damage produces receptive aphasia rather than deafness.

The duplicate sequential bias accounts for the left hemisphere’s dominance in grammar, syntax, phonology, reading, writing, and the processing of unfamiliar or nonsense words. These operations require the brain to analyse speech or text into parts, apply rules, and assemble meaning step by step. The left inferior frontal gyrus, including Broca’s area, supports the production of structured speech, while left temporal regions support lexical access and semantic organisation. The left hippocampus shows a similar bias, supporting verbal and narrative memory: information that can be ordered, described, and retrieved in linguistic form.

Emotion in the left hemisphere tends to be processed more slowly and reflectively, particularly when it is linked to language and conscious appraisal. The left amygdala is more involved when emotional experience is interpreted, labelled, or evaluated in words. This does not mean that the left hemisphere is unemotional; rather, it processes emotion in a manner consistent with its broader analytical and symbolic style.

In contrast, the right hemisphere is biased towards processing information holistically, contextually, and in parallel. It is well-suited to information that does not depend on sequence or explicit rules but instead relies on patterns, relationships, and overall configuration. This explains its dominance in music, prosody, spatial cognition, and social perception. Musical melody and harmony are perceived as patterns rather than ordered symbols. Facial recognition depends on the configuration of features rather than individual parts. Spatial awareness requires integrating multiple cues simultaneously to form a coherent sense of layout.

The right temporal lobe plays a key role in processing non-linguistic sounds, including music, environmental noises, and animal calls. It is also critical for emotional prosody: the tone, rhythm, and intonation of speech that convey emotion independently of the words themselves. A person with right hemisphere damage may speak fluently and grammatically, yet sound flat or emotionally inappropriate, because the emotional contour of speech is lost, even though linguistic structure is preserved.

The right amygdala shows a corresponding bias. It is more strongly involved in rapid, automatic emotional responses, particularly those related to threat and fear. These responses occur quickly, often before conscious verbal interpretation. This aligns with the right hemisphere’s broader role in rapid, global appraisal of situations rather than deliberate analysis. The right hippocampus mirrors this pattern by supporting spatial memory and navigation: remembering places, routes, and environments experienced as wholes rather than as narratives.

What matters is that these lateralised functions are not independent facts that must be memorised separately. They are expressions of the same underlying difference in processing style. Language structure, exact calculation, and verbal memory cluster in the left hemisphere because they all depend on sequential, rule-based organisation. Music, emotion, spatial awareness, and social meaning cluster in the right hemisphere because they depend on pattern, context, and integration.

This is why lateralisation is best understood synoptically. The hemispheres are not divided into “logical” and “creative” sides, nor into lists of tasks. They represent two complementary ways of making sense of the world: one that breaks experience into ordered components, and one that integrates experience into meaningful wholes. Neuroanatomy, lesion evidence, and subcortical structures such as the amygdala and hippocampus all support this interpretation, not as a slogan, but as a consistent explanatory framework.

EVIDENCE FOR HEMISPHERIC LATERALISATION

HOW DO WE KNOW THE BRAIN IS LATERALISED?

Evidence for hemispheric lateralisation comes from cognitive neurology, animal studies, cognitive science experiments, and split-brain research.

Please click here for more details on these methods.

The key idea students need to grasp is this: If damage to the same area on the left and right sides of the brain produces different effects, the function is lateralised.

LANGUAGE – LEFT HEMISPHERE

Broca (1861)

Method: Cognitive neurology (post-mortem case study)

Discovery: Loss of speech production with preserved comprehension

Brain area: Left inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area)

Conclusion: Speech production is lateralised to the left hemisphere

Wernicke (1874)

Method: Cognitive neurology (post-mortem case studies)

Discovery: Fluent but meaningless speech and impaired comprehension

Brain area: Left posterior temporal lobe (Wernicke’s area)

Conclusion: Language comprehension is lateralised to the left hemisphere

Penfield (1950s)

Method: Intraoperative electrical stimulation

Discovery: Temporary stimulation of the left language areas stopped speech; right-side stimulation did not

Brain area: Left inferior frontal and temporal language regions

Conclusion: Causal evidence for left-hemisphere language dominance

VISUOSPATIAL AND FACE PROCESSING – RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Hemispatial neglect (1940s–present)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion studies)

Discovery: Patients ignore one side of space, typically the left

Brain area: Right parietal lobe

Conclusion: Spatial attention is lateralised to the right hemisphere

FACE BLINDNESS

Prosopagnosia/face blindness (Bodamer, 1947)

Method: Cognitive neurology (case study)

Discovery: Inability to recognise faces despite intact vision

Brain area: Right fusiform gyrus (fusiform face area)

Conclusion: Face recognition is lateralised to the right hemisphere

Visual agnosia (mid-20th century)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion studies)

Discovery: Inability to recognise objects despite intact visual input

Brain area: Right occipito-temporal regions

Conclusion: Object and pattern recognition shows right-hemisphere bias

AUDITORY AND EMOTIONAL PROCESSING – RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Aprosodia (Ross, 1981)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion studies)

Discovery: Loss of emotional tone in speech with intact grammar and vocabulary

Brain area: Right temporal lobe

Conclusion: Emotional prosody is lateralised to the right hemisphere

Dichotic listening (Kimura, 1961)

Method: Cognitive science experiments

Discovery: Right-ear advantage for speech; left-ear advantage for music and non-verbal sound

Brain area: Left hemisphere (speech), right hemisphere (non-verbal sound)

Conclusion: Auditory processing is functionally lateralised

MEMORY AND EMOTION – SUBCORTICAL LATERALISATION

H.M. (1953)

Method: Cognitive neurology (surgical ablation case study)

Discovery: Inability to form new long-term memories

Brain area: Hippocampus (bilateral removal)

Conclusion: Memory formation depends on the hippocampus; later work shows left bias for verbal memory and right bias for spatial memory

Amygdala lesion studies (1950s–present)

Method: Animal studies and cognitive neurology

Discovery: Reduced fear responses following right amygdala damage; altered emotional evaluation following left amygdala damage

Brain area: Amygdala

Conclusion: Emotional processing shows hemispheric bias

DELUSIONAL MISIDENTIFICATION – RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Capgras syndrome (Capgras & Reboul-Lachaux, 1923)

Method: Cognitive neurology (case studies)

Discovery: Belief that an impostor has replaced a familiar person

Brain area: Right temporal and frontal regions

Conclusion: Face recognition and emotional familiarity are right-hemisphere biased

Reduplicative paramnesia (Pick, 1903)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion studies)

Discovery: Belief that places or people exist in duplicate

Brain area: Right frontal and parietal regions

Conclusion: Spatial and contextual integration is lateralised to the right hemisphere

LANGUAGE AND READING – LEFT HEMISPHERE

Pure alexia/word blindness (Dejerine, 1892)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion case study)

Discovery: Inability to read written words despite intact vision and speech

Brain area: Left occipito-temporal region (visual word form area)

Conclusion: Reading is lateralised to the left hemisphere

Acquired dyslexia (mid-20th century)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion studies)

Discovery: Loss of previously intact reading ability following left-hemisphere damage

Brain area: Left temporal and parietal language regions

Conclusion: Literacy processing shows left-hemisphere dominance

MUSIC – RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Amusia (Henschen, 1919; modern lesion studies)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion case studies)

Discovery: Loss of ability to recognise melody, pitch, or harmony despite intact hearing

Brain area: Right temporal lobe

Conclusion: Musical perception is lateralised to the right hemisphere

SELF-AWARENESS AND BODY REPRESENTATION – RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Anosognosia (Babinski, 1914)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion case studies)

Discovery: Lack of awareness of one’s own paralysis or deficit

Brain area: Right parietal lobe

Conclusion: Self-monitoring and awareness of bodily state are right-hemisphere biased

VISUAL INTEGRATION AND MEANING – RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Visual agnosia (Lissauer, 1890)

Method: Cognitive neurology (lesion studies)

Discovery: Inability to recognise objects despite intact visual input

Brain area: Right occipito-temporal regions

Conclusion: Visual meaning and integration show right-hemisphere bias

EMOTION AND MUSIC

Affective amusia (late 20th century)

Method: Cognitive neurology and experimental studies

Discovery: Inability to recognise emotional tone in music

Brain area: Right temporal and frontal regions

Conclusion: Emotional interpretation of sound is right-hemisphere lateralised

CORE TAKEAWAY

Across language, reading, music, face recognition, spatial awareness, emotion, and self-awareness, damage to homologous regions in the left and right hemispheres produces different outcomes. This asymmetry provides converging evidence that many higher cognitive functions are hemispherically lateralised, not merely localised.

EVALUATION

RESEARCH EVALUATION FOR HEMISPHERIC LATERALISATION

Research into hemispheric lateralisation examines whether higher cognitive functions exhibit a systematic bias toward one hemisphere rather than being evenly distributed across the brain. Importantly, this question has been addressed using multiple independent research methods, most of which involve neurologically typical individuals.

A large body of evidence comes from experimental studies with healthy participants, particularly using divided-field paradigms and dichotic listening. These techniques were designed to examine hemispheric processing in intact brains, where information typically transfers rapidly between hemispheres via the corpus callosum. By presenting competing stimuli briefly and simultaneously to each visual hemifield or auditory ear, researchers revealed consistent processing biases. Although these effects are subtle, they are highly reliable across large samples, indicating that lateralisation operates as a bias in information processing rather than an absolute division of labour.

Further support comes from neuroimaging studies, including fMRI and PET. These methods enable direct measurement of brain activity in large, representative samples. Across thousands of studies, language tasks consistently show greater activation in left-hemisphere networks, while visuospatial, facial, and emotional processing show greater right-hemisphere involvement. In the majority of individuals, typically reported as over 95%, this left-language/right-visuospatial pattern is observed. This provides strong evidence that lateralisation characterises the neurotypical brain, rather than being an artefact of rare neurological cases.

Additional evidence comes from case studies of focal brain damage resulting from strokes, tumours, head injuries, and neurological disease. Across many unrelated cases, damage to the left hemisphere disproportionately disrupts language functions, while damage to the right hemisphere more commonly affects visuospatial processing, emotional prosody, and face recognition. The recurrence of these patterns across different causes of injury strengthens the case for hemispheric specialisation of higher cognitive functions.

At the same time, lateralisation is not universal. A minority of individuals exhibit atypical patterns, including left-handers with reversed hemispheric dominance and individuals with bilateral language representation. These findings indicate that lateralisation reflects population-level tendencies rather than fixed rules, and that developmental, genetic, and hormonal factors influence hemispheric organisation.

Overall, the research evidence supports the conclusion that the human brain is functionally lateralised for higher cognitive processes, particularly language and visuospatial processing. This conclusion does not rest on a single method or population, but on converging findings from experimental psychology, neuroimaging, and neurological case studies. While lateralisation is probabilistic rather than absolute, the consistency of results across methods provides substantial grounds for accepting hemispheric specialisation as a core feature of human brain organisation.

MISAPPLICATION AND OVERSIMPLIFICATION

The idea that individuals can be categorised as “left-brained” or “right-brained” is a widely recognised oversimplification of hemispheric lateralisation. Although specific functions show reliable hemispheric bias, neuroimaging research demonstrates that both hemispheres are active during most cognitive tasks, and lateralisation is rarely absolute. Functions are distributed across networks, with one hemisphere often contributing more strongly than the other, rather than operating in isolation.

Early interpretations of lateralisation sometimes portrayed hemispheric differences as rigid and mutually exclusive, a view that has since been revised. Contemporary evidence shows that hemispheric involvement is task-dependent and context-sensitive, with the degree of lateralisation varying across individuals and situations. For example, while language processing typically shows a left-hemisphere bias and visuospatial processing a right-hemisphere bias, both hemispheres contribute to each domain.

Psychologist Terence Hines has argued that while research on hemispheric lateralisation is scientifically robust, it has been repeatedly misapplied outside academic contexts. Popular and commercial claims linking lateralisation to personality types, learning styles, management ability, or psychological therapies extend far beyond the evidence base and are not supported by neuroscience.

SEX DIFFERENCES AND HEMISPHERIC LATERALISATION

Early theories of hemispheric lateralisation were heavily shaped by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century gender ideology. The left hemisphere was associated with rationality, logic, and control. It was therefore labelled as masculine, whereas the right hemisphere, associated with emotion, intuition, and creativity, was labelled as feminine. These claims were not based on neuroscientific evidence. They were frequently used to justify sexist and discriminatory views, portraying the right hemisphere as inferior and associating it with women, children, criminals, and the mentally ill. Such assumptions appeared not only in early psychology but also in literature, including works such as The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. These interpretations are now recognised as cultural projections rather than scientific findings.

There are reliable average sex differences in cognitive abilities that relate to hemispheric lateralisation. These differences are statistical rather than absolute and arise from biological factors, particularly prenatal androgen exposure, interacting with developmental processes.

On average, females perform better in language-related abilities. This includes earlier language acquisition, larger active vocabularies, greater verbal fluency, and more efficient word retrieval. Females also tend to show greater bilateral language representation, with both hemispheres contributing to language processing. This reduced lateralisation is associated with greater resilience to unilateral brain damage and supports more nuanced verbal and social communication.

Females also, on average, perform better in recognising non-verbal communication (NVC). Non-verbal communication is right-hemisphere lateralised, relying particularly on the right temporal lobe and right frontal regions, which are involved in emotional prosody, facial expression recognition, and the interpretation of social cues. This includes sensitivity to tone of voice, facial emotion, gesture, and body language. Stronger engagement of these right-hemisphere systems, alongside left-hemisphere language networks, supports more accurate decoding of social and emotional information. Higher average empathy scores in females are consistent with behavioural findings and neuroimaging evidence showing greater activation in right-lateralised networks for emotional and social cognition.

In contrast, males perform, on average, better on visuospatial tasks, including mental rotation, spatial navigation, and three-dimensional manipulation. These abilities are strongly associated with right-hemisphere processing, particularly in the parietal and occipitotemporal regions involved in spatial integration and global visual processing. Males also tend to show stronger hemispheric lateralisation overall, especially for language, meaning that functions are more clearly biased to one hemisphere.

Biological explanations for these patterns focus on the role of androgens, particularly testosterone, during prenatal development. Exposure to higher levels of testosterone in utero influences neuronal migration, synaptic pruning, and the timing of hemispheric development. The Geschwind–Galaburda framework proposes that elevated prenatal testosterone delays left-hemisphere maturation, thereby allowing the right hemisphere to attain greater functional dominance. While the original model has been refined, substantial evidence supports the role of prenatal hormones in shaping hemispheric organisation and cognitive bias.

From an evolutionary perspective, these differences are consistent with division of cognitive specialisation rather than superiority. Enhanced language, social sensitivity, and emotional communication would have supported cooperative childcare and social cohesion, while enhanced spatial processing would have supported navigation, hunting, and tool use. These pressures would favour average differences rather than categorical separation.

Crucially, variation within each sex is significant, and distributions overlap considerably. Many females outperform males on visuospatial tasks, and many males outperform females on verbal tasks. Handedness, genetics, early experience, education, bilingualism, and neural plasticity all influence lateralisation. Sex predicts tendencies, not individual capacity.

HANDEDNESS, ATYPICAL LATERALISATION, AND BRAIN ORGANISATION

Handedness is one of the most visible indicators of hemispheric organisation, but it is an imperfect proxy for lateralisation. While the majority of right-handed individuals show a typical pattern of hemispheric specialisation—left-hemisphere dominance for language and right-hemisphere dominance for visuospatial processing—this pattern is less consistent in left-handed individuals. Research shows that left-handed people are more likely to display atypical lateralisation, including bilateral language representation, mirror-reversed organisation, or mixed patterns of dominance across different functions.

Mirror-reversed organisation refers to individuals who show the opposite of the typical pattern, such as right-hemisphere language dominance and left-hemisphere visuospatial bias. Bilateral organisation involves functions such as language being distributed across both hemispheres rather than being strongly lateralised. Mixed organisation refers to crossed dominance across systems—for example, left-handedness combined with right-eye dominance or left-ear dominance for language. These patterns demonstrate that hemispheric organisation is not binary but exists along a continuum.

One implication of bilateral or mixed organisation is that functional efficiency may be reduced for tasks that benefit from strong lateralisation. Neurotypical organisation allows the two hemispheres to specialise and process information in parallel, thereby reducing cognitive load and interference. In contrast, bilateral language representation may lead to competition between hemispheres, increasing processing time and reducing fluency under demanding conditions. This has been proposed as one reason why some left-handed individuals show higher rates of language-based difficulties, such as dyslexia or stuttering. However, these outcomes are probabilistic rather than inevitable.

However, an atypical organisation can also confer advantages, particularly with respect to resilience to brain injury. Individuals with bilateral language representation are often less severely affected by unilateral stroke or trauma, as the intact hemisphere can support language functions. This highlights an essential trade-off between efficiency and redundancy in brain organisation.

Extreme cases illustrate both the costs and consequences of atypical organisation. Kim Peek, often cited as a savant case, had agenesis of the corpus callosum, resulting in minimal interhemispheric communication. Rather than showing typical lateralisation, Peek demonstrated functional independence of the hemispheres, with exceptional memory abilities but profound impairments in everyday functioning, motor coordination, and abstraction. His case illustrates that hemispheric specialisation and interhemispheric integration are both critical: lateralisation without integration, or integration without specialisation, is insufficient for everyday cognition.

Overall, handedness and hemispheric organisation complicate simple models of lateralisation. While neurotypical patterns appear to maximise processing efficiency through functional separation, atypical patterns such as bilateral, mirror-reversed, or mixed organisation demonstrate that the brain can develop in multiple viable configurations. These findings challenge rigid localisation models and support a more nuanced view in which lateralisation reflects probabilistic developmental biases, shaped by genetics, hormones, and experience rather than fixed rules.

t

KIM PEEK.

CASE STUDY: KIM PEEK AND ATYPICAL BRAIN ORGANISATION

Kim Peek (1951–2009) is a well-documented case illustrating the importance of hemispheric organisation and interhemispheric communication. Neuroimaging revealed that Peek was born with agenesis of the corpus callosum, meaning the primary structure connecting the two hemispheres was absent. As a result, the left and right hemispheres were unable to integrate information.

Peek did not show standard hemispheric lateralisation. Instead, his brain functioned in a highly atypical and fragmented manner, with each hemisphere operating relatively independently. He demonstrated extraordinary abilities in specific domains, particularly memory, memorising entire books with remarkable accuracy, often reading one page with each eye simultaneously. However, despite these exceptional skills, he showed profound impairments in everyday functioning, including poor motor coordination, limited abstract reasoning, and difficulties with social understanding.

Peek’s case highlights that normal cognition depends not only on lateralisation but also on effective integration between hemispheres. While some degree of specialisation enables efficient processing, this must be balanced against interhemispheric communication. In Peek’s case, reduced integration prevented the coordination of specialised functions, resulting in pronounced cognitive unevenness: isolated strengths alongside significant deficits.

As an AO3 point, Kim Peek’s case demonstrates that atypical brain organisation can produce both exceptional abilities and serious functional costs. It challenges simplistic assumptions that more or less lateralisation is inherently better and instead supports the view that neurotypical patterns of hemispheric specialisation, combined with interhemispheric integration, optimise cognitive efficiency.

PLASTICITY AND HEMISPHERIC LATERALISATION

Hemispheric lateralisation is not fixed at birth. While there are strong developmental biases for certain functions to become lateralised to one hemisphere, the brain retains a capacity for functional plasticity, particularly during childhood. Functional plasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganise functions, either by recruiting alternative neural circuits within the same hemisphere or by shifting processing to the opposite hemisphere following damage.

Evidence for plasticity comes most clearly from early brain injury. When damage to a left-hemisphere language area occurs in early childhood, language functions can sometimes reorganise to the right hemisphere, resulting in relatively normal language development despite significant left-hemisphere damage. This reorganisation is far less likely in adults, indicating that plasticity is age-dependent. As development progresses, lateralisation becomes more entrenched and functional reassignment becomes increasingly limited.

This does not mean that lateralisation disappears. Instead, plasticity operates within constraints. Strongly lateralised functions, such as language, can shift hemispheres early in development, but the reorganised system is often less efficient than the typical arrangement. Individuals with right-hemisphere language following early left-hemisphere damage frequently show subtle deficits in fluency, processing speed, or higher-level language use. This supports the idea that neurotypical lateralisation reflects an optimised configuration rather than an arbitrary one.

Plasticity also helps explain individual differences in lateralisation. Bilateral language representation, more common in left-handed individuals, may reflect developmental plasticity in response to genetic or hormonal factors that weaken early hemispheric bias. While this bilateral organisation can provide resilience to unilateral injury, it may also increase interhemispheric competition, reducing processing efficiency for tasks that benefit from strong lateralisation.

Importantly, plasticity does not imply that “any part of the brain can do any job”. Sensory and motor cortices show limited functional reassignment, and higher-order functions can only relocate to regions with compatible circuitry. Plasticity, therefore, modifies lateralisation but does not erase it.

In adulthood, plasticity is more limited and typically involves compensation rather than reassignment. Following stroke or injury, intact regions may increase activity to support impaired functions, but the original hemispheric bias usually remains evident. Neuroimaging studies indicate that recovery often involves increased bilateral activation, reflecting compensatory recruitment rather than accurate functional transfer.

Overall, functional plasticity and lateralisation are not opposing principles. Lateralisation reflects developmental specialisation, while plasticity reflects adaptive flexibility. Together, they explain why hemispheric biases are reliable at the population level, yet variable and modifiable at the individual level, particularly during early development.

CONSCIOUSNESS IS LATERALIZED

SPLIT-BRAIN STUDIES

Split-brain patients rapidly regained functional stability after having their corpus callosum severed. Within weeks or months, they were often difficult to distinguish from neurologically typical individuals in everyday life. Importantly, patients also reported a restored sense of personal unity. Subjectively, they experienced themselves as a single, coherent individual, even though experimental testing could still reveal hemispheric dissociations.

This apparent paradox became a central focus of Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga’s work. Sperry and Gazzaniga investigated why split-brain patients continued to experience a unified sense of self despite the physical separation of their hemispheres. His answer was what he termed the “interpreter” function of the left hemisphere.

In a series of experiments, they presented information to the right hemisphere and then asked patients to explain their resulting behaviour verbally, a task typically mediated by the left hemisphere. He found that when the left hemisphere lacked access to the relevant information, it nonetheless produced a plausible post hoc explanation.

In a well-known experiment, a patient was shown a picture of a chicken foot to the left hemisphere and a snowy scene to the right hemisphere. When asked to select related images, the left hemisphere selected a chicken, whereas the right hemisphere selected a shovel. When asked why the shovel had been selected, the patient stated that it was needed to clean out the chicken shed. The explanation was coherent, but incorrect. The left hemisphere was unaware of the snowy scene and instead generated a narrative that made sense of the observed action.

From this and similar findings, Gazzaniga proposed that the left hemisphere contains an interpretive system that continuously constructs explanations for behaviour, even when it lacks complete information. This system contributes to the strong human sense of coherence and agency by weaving actions, perceptions, and outcomes into a single narrative.

Gazzaniga argued that this interpretive process is not unique to patients with split brains. In neurologically typical individuals, the corpus callosum facilitates integration of information from both hemispheres before explanation. However, the explanatory mechanism itself remains the same: the brain generates a unified account of behaviour, whether or not that account fully reflects the underlying neural causes.

Crucially, Gazzaniga did not claim that humans are composed of multiple independent consciousnesses, nor that the sense of unity is simply an illusion. Instead, he argued that the feeling of unity is an active construction of the brain, arising from the coordination of specialised systems and the narrative functions of the left hemisphere. The interpreter does not invent behaviour, but it does organise experience into a form that feels continuous, intentional, and self-directed.

In this way, split-brain research did not undermine the concept of a unified self. Instead, it revealed how that unity is achieved. The sense of being a single person is not evidence that the brain is a single, undifferentiated system, but evidence that it possesses powerful mechanisms for integration, explanation, and self-representation.

EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATIONS FOR HEMISPHERIC LATERALISATION

From an evolutionary perspective, hemispheric lateralisation is understood as an adaptation that improves efficiency, speed, and survival. A brain in which both hemispheres attempt to perform the same tasks simultaneously would be slower, more metabolically costly, and more prone to interference. Dividing cognitive labour between hemispheres allows organisms to process different types of information in parallel, increasing behavioural flexibility in complex environments.

Clear examples of this can be seen in non-human animals, particularly birds. Many bird species show strong lateralisation of visual processing. Typically, the right hemisphere is specialised for detecting predators, monitoring the wider environment, and responding to threats. In contrast, the left hemisphere is specialised for acceptable visual discrimination involved in feeding, such as pecking seeds or manipulating food. This division allows a bird to eat while simultaneously remaining vigilant. A non-lateralised bird would be forced to alternate between these tasks, reducing its chances of survival. Importantly, this pattern is consistent across species, suggesting that lateralisation is not a cultural artefact but an evolved biological solution.

Human lateralisation can be understood as an extension of this principle to more complex cognitive demands. The right hemisphere remains specialised for processing global patterns, environmental context, emotional tone, and biologically salient signals. For humans, this includes detecting sudden sounds, recognising threat-related cues, interpreting facial expressions, and responding rapidly to environmental changes. Hearing an animal growl, a sudden noise in the dark, or thunder signalling danger requires fast, holistic processing rather than detailed analysis.

At the same time, humans evolved increasingly complex social structures and communication systems. This placed intense selective pressure on the left hemisphere to specialise in sequential, symbolic processing. Language allows humans not only to respond to danger but also to name and describe it, and to coordinate group responses. A warning shout, a hunting strategy, or a shared plan depends on ordered sounds, syntax, and meaning. Left-hemisphere specialisation for language, therefore, complements right-hemisphere threat detection by transforming raw perception into coordinated social action.

Crucially, lateralisation allows these processes to operate simultaneously. A human can monitor the environment for danger using right-hemisphere systems while engaging in language-based planning and communication using left-hemisphere systems. This parallel processing would have been a significant evolutionary advantage in hunting, defence, and social cooperation. Without lateralisation, these competing demands would interfere with one another, slowing response times and increasing error.

The evolutionary value of lateralisation is further supported by its presence across species and sensory modalities. It appears in vision, audition, emotion, and motor control, long before the emergence of human language. In humans, language did not create lateralisation; instead, language colonised an already lateralised brain, exploiting left-hemisphere capacities for sequence and symbol manipulation that had evolved earlier for other purposes.

In this sense, hemispheric lateralisation reflects a general evolutionary principle: complex organisms benefit when different neural systems specialise in different kinds of processing, provided those systems can still be integrated when needed. The corpus callosum allows that integration in humans, enabling specialised hemispheres to produce coherent behaviour and unified experience