SPLIT BRAIN RESEARCH

SPECIFICATION: Hemispheric Lateralisation & Split Brain Research: Lateralisation is the idea that the two hemispheres of the brain are functionally different and that each hemisphere has functional specialisations, e.g., the left hemisphere is dominant for language, and the right hemisphere excels at visuomotor tasks.

BRAIN TERMINOLOGY RELATED TO LATERALISATION

LATERAL AND MEDIAL

Lateral (from Latin lateralis, meaning “to the side”) refers to the sides of an animal, as in “left lateral” and “right lateral”. The term medial (from Latin medius, meaning “middle”) refers to structures near the centre of an organism, the median plane. For example, in a fish, the gills are medial to the operculum but lateral to the heart.CONTRALATERAL

(from Latin contra, meaning “against”): on the side opposite to another structure. For example, the left arm is contralateral to the right arm, or the right leg.IPSILATERAL

(from Latin ipse, meaning “same”): on the same side as another structure. For example, the left arm is ipsilateral to the left leg.BILATERAL

(from Latin bi, meaning “two”): on both sides of the body. For example, bilateral orchiectomy (removal of testes on both sides of the body’s axis) is surgical castration.UNILATERAL

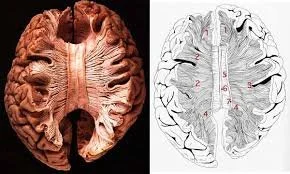

(from Latin uni, meaning “one”): on one side of the body. For example, unilateral paresis is hemiparesis.CORPUS CALLOSUM

A massive bundle of nerve fibres (axons) which connects the two cerebral hemispheres. There are over 200 million axons, as many as ten times more than the spinal cord.COMMISSUROTOMY

Surgically cutting nerve fibre tracts which connect the two hemispheres

CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES AND LATERALISATION OF FUNCTION

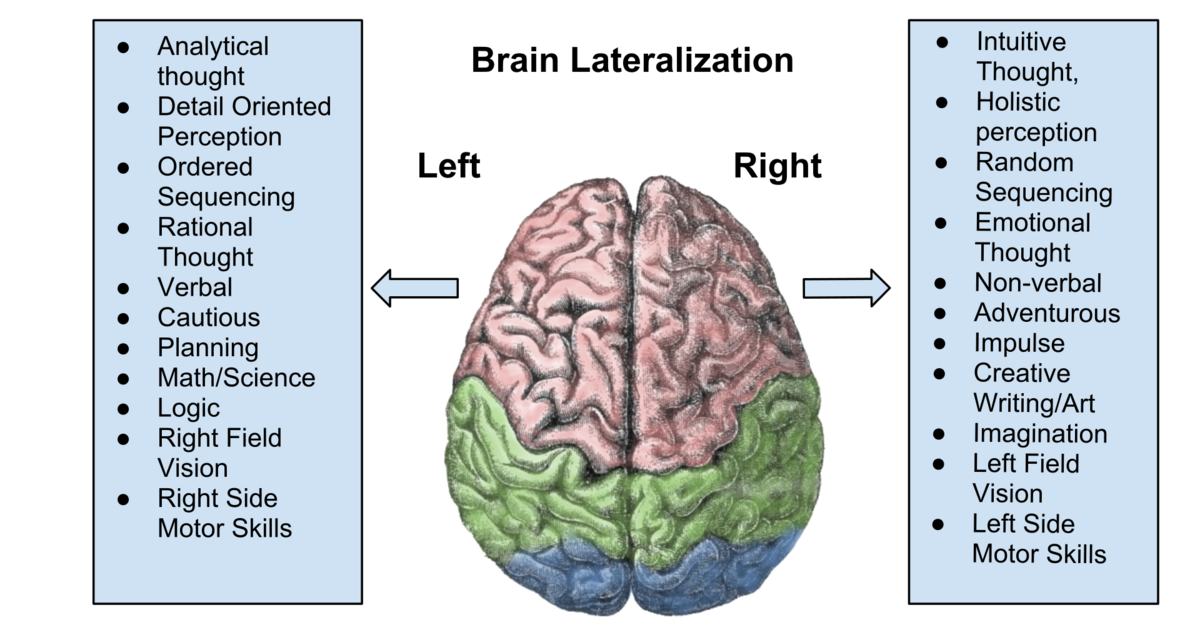

The cerebrum is divided into two hemispheres, the left and the right, separated by the longitudinal fissure. Although the hemispheres appear broadly symmetrical in structure, they are not functionally identical. Specific cognitive and perceptual functions are lateralised, meaning they are primarily controlled by one hemisphere rather than the other.

This has sometimes led to the misleading idea of “left-brained” or “right-brained” people. This way of thinking is incorrect. Lateralisation does not describe different types of people or personalities, and it does not mean that the hemispheres operate as separate brains. Instead, it refers to the fact that specific functions are mainly located in one hemisphere.

For example, language structure, including grammar and syntax, is typically controlled by the left hemisphere. In contrast, the right hemisphere primarily controls visuospatial processing, face recognition, and specific aspects of music perception. These functions are genuinely one-sided with respect to the location of their core neural mechanisms. Damage to the relevant hemisphere can therefore selectively impair these abilities.

At the same time, many complex behaviours require complementary contributions from both hemispheres. This does not mean that the two hemispheres perform the same function; instead, they handle different aspects of the same task. For instance, in vision, the left hemisphere is more involved in processing fine detail and local features. In contrast, the right hemisphere is more involved in processing overall shape, spatial relationships and global patterns. In language, the left hemisphere controls grammatical structure and literal meaning, while the right hemisphere contributes to intonation, emotional tone and pragmatic context.

Under normal conditions, these lateralised and complementary processes are integrated through continuous communication between the hemispheres via the corpus callosum, a large bundle of approximately 200–250 million nerve fibres. This communication allows information processed in one hemisphere to influence behaviour and perception as a whole. A smaller pathway, the anterior commissure, also connects parts of the hemispheres, but the corpus callosum is the main route of interhemispheric transfer.

Evidence from studies of neurological damage and split-brain patients shows that when this communication is disrupted, lateralised functions remain one-sided, but their separation becomes more pronounced. Under typical conditions, however, the hemispheres work together to produce a unified experience.

In summary, lateralisation refers to the organisation of specific functions in one hemisphere, whereas many everyday tasks depend on complementary processing across both hemispheres, coordinated through constant communication.

CONTRALATERAL ORGANISATION, HANDEDNESS AND HEMISPHERIC DOMINANCE

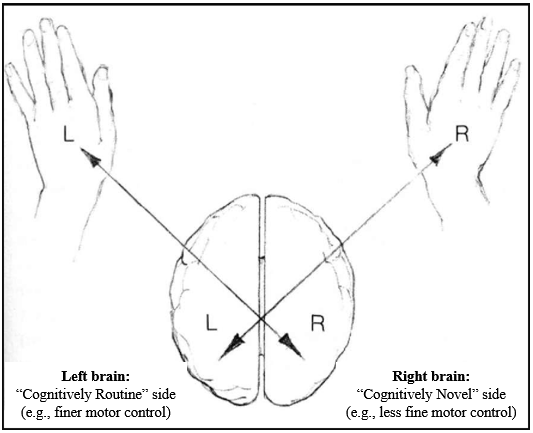

The human brain is organised contralaterally, meaning that each cerebral hemisphere primarily controls movement and processes sensory information from the opposite side of the body and sensory space. In most people, the left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and receives information mainly from the right visual field and right ear. In contrast, the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body and receives information mainly from the left visual field and left ear. This contralateral organisation applies to motor control and to major sensory systems, including vision and hearing.

Accordingly, handedness is not a superficial preference. The fact that most people are right-handed reflects that, in most individuals, the left hemisphere controls fine motor output and is also dominant for language. This means that, for most right-handed people, language processing and motor output for tasks such as speaking or writing are primarily processed in the left hemisphere. This alignment is neurologically efficient because it minimises the need for information to cross between hemispheres.

Contralateral organisation also applies to sensory input. In vision, information from the right visual hemifield of both eyes is processed by the left hemisphere, whereas the right hemisphere processes information from the left visual hemifield. In hearing, although both ears project to both hemispheres, auditory pathways are predominantly contralateral, such that sounds entering the right ear are processed mainly by the left hemisphere, and sounds entering the left ear are processed mainly by the right hemisphere. This organisation underlies the use of dichotic listening tasks to assess hemispheric dominance for auditory and language processing.

Importantly, lateralisation does not develop as a single global switch. Different systems lateralise independently; as a result, individuals may exhibit cross-dominance, such as being right-handed but left-eyed, left-handed but right-footed, or having mismatched motor and sensory dominance. This variability reflects normal developmental variation, not abnormality. Sensory dominance can also be shaped by experience or constraint, for example, when one sensory channel is consistently relied upon more than another.

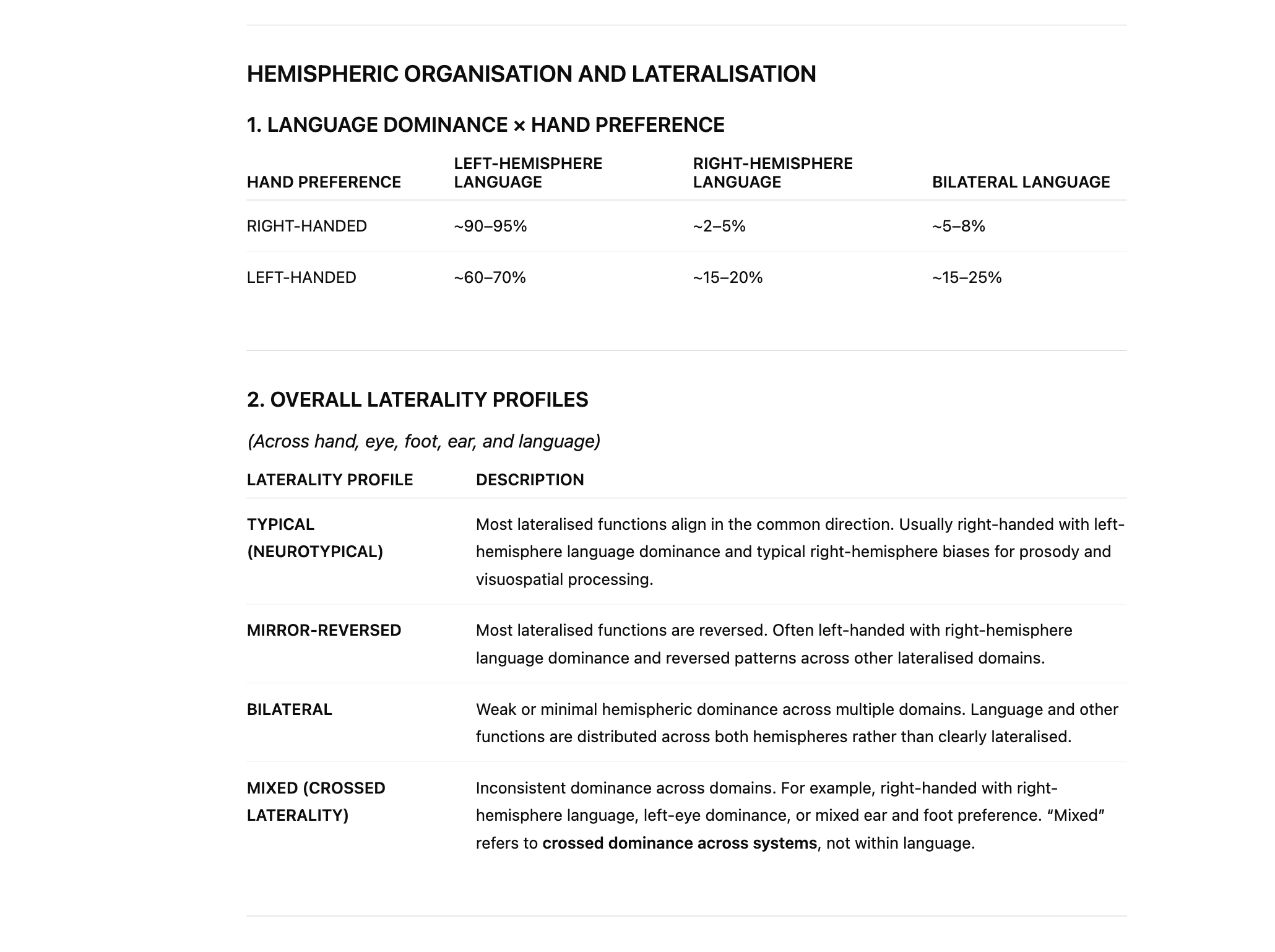

Because of contralateral organisation, handedness is closely related to—but does not rigidly determine—hemispheric dominance for language. In most right-handed individuals, language is left-hemisphere dominant. The same is true for a substantial proportion of left-handed individuals; however, overall brain organisation is more variable in left-handers. Some left- and right-handed individuals show a mirror-reversed pattern, with language-dominant processing in the right hemisphere and visuospatial processing in the left hemisphere. In this arrangement, language processing and motor control of the dominant hand remain aligned within the same hemisphere, and no additional interhemispheric transfer is required.

However, the most common pattern in left-handers is not mirror reversal. Around 60–70% of left-handed individuals still show left-hemisphere language dominance, as in right-handers. In these individuals, language is processed in the left hemisphere, while the right hemisphere governs control of the left hand. As a result, language-related information must cross the corpus callosum more frequently to guide motor output. This increased reliance on interhemispheric transfer is what is meant here by double wiring. Language processing occurs in one hemisphere, whereas motor execution occurs in the other, necessitating additional interhemispheric communication.

This arrangement functions well for most everyday activities. Still, it places greater demands on interhemispheric communication, particularly for tasks requiring rapid and precise symbol manipulation, such as reading, spelling, writing and arithmetic. This helps explain why language- and number-based learning difficulties, such as dyslexia and dyscalculia, are more prevalent in populations with atypical or less efficient hemispheric alignment. This relationship is probabilistic rather than causal: most left-handed individuals do not have dyslexia or dyscalculia, and most individuals with these difficulties are right-handed. The increased vulnerability reflects wiring efficiency and developmental load, not brain damage.

Some individuals exhibit bilateral organisation of functions, such as language, meaning that both hemispheres contribute substantially rather than one hemisphere being clearly dominant. This pattern is more common in left-handers but also occurs in a minority of right-handers. Bilateral organisation can sometimes confer resilience following brain injury, but it may also reduce the efficiency associated with strong hemispheric specialisation.

Older claims that left-handedness reflects brain damage are incorrect and outdated. These ideas arose from early observations of individuals who developed atypical lateralisation following early brain injury and were wrongly generalised. Modern evidence shows that left-handedness reflects normal variation in developmental wiring, not pathology. Mirror twins provide further evidence for this, demonstrating that left–right asymmetries, including handedness and language dominance, can be developmentally reversed without impairment.

Current large-scale research indicates that left-handedness is more common than once thought, but estimates vary depending on how handedness is defined. Using strict definitions of consistent left-hand dominance, around 10–11% of the population is left-handed. When broader definitions that include mixed or task-dependent handedness are used, the prevalence rises to 15–18%, with some recent Western cohorts approaching 20%. Left-handedness is slightly more common in males, and true ambidexterity remains rare, typically occurring in fewer than 1%.

In summary, contralateral organisation explains why handedness matters, why most people show left-hemisphere language dominance, and why left-handedness is associated with greater variability in hemispheric organisation. In particular, patterns involving double wiring increase reliance on interhemispheric transfer, helping to explain both the strengths and vulnerabilities observed across individuals, including increased susceptibility to dyslexia and dyscalculia in some developmental trajectories.

EEG READINGS

EPILEPSY

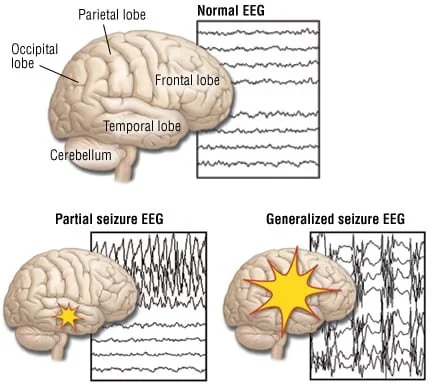

Roger Sperry’s split-brain research emerged from the clinical treatment of patients with severe, intractable epilepsy. Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterised by abnormal patterns of electrical activity in the brain, most commonly originating from a focal area of dysfunction. This dysfunction may arise from identifiable damage such as head injury, stroke, tumours or infections, but epilepsy may also be linked to genetic vulnerability, epigenetic influences or neurodevelopmental abnormalities. In many cases, however, no single definitive cause can be identified.

Whatever its origin, epilepsy reflects disrupted brain structure or signalling. Structural abnormalities and damaged neural pathways disrupt everyday communication between neuronal networks, leading to unstable, poorly regulated activity. In effect, the brain loses its ability to control the timing and coordination of neural firing. This breakdown in regulation allows electrical activity to escalate uncontrollably, producing recurrent seizures.

At the neuronal level, seizures involve uncontrolled action potentials (electrical firing) spreading across neuronal networks, creating widespread, synchronised electrical activity. Instead of neurons firing in a regulated, task-specific manner, large populations of neurons fire simultaneously, overwhelming multiple brain functions.

In mild epilepsy, this abnormal activity may remain localised and brief, producing momentary lapses in awareness or minor motor disturbances. For example, absence seizures involve brief periods of staring and loss of awareness, often lasting only a few seconds. In contrast, focal seizures originate in a specific brain region and may cause localised motor movements, sensory disturbances, or altered consciousness without full loss of awareness. In severe cases, however, the abnormal electrical activity can spread rapidly across the cortex, leading to generalised seizures that involve multiple brain regions, such as tonic-clonic seizures. These seizures often involve loss of consciousness, convulsions, physical injury and significant cognitive disruption. For many patients, seizures were frequent, unpredictable and largely untreatable at the time, making epilepsy profoundly disabling and, in some cases, life-threatening.

CORPUS CALLOSUM

COMMISUROTOMY

Before the development of modern anti epileptic drugs, clinicians observed that seizures often begin in a localised region of the brain, known as a seizure focus, but can rapidly propagate beyond this area. Abnormal electrical activity is not confined to a single pathway or hemisphere; instead, it can spread across multiple cortical and subcortical regions, including the motor cortex, sensory cortex, temporal lobes, thalamus and associated brainstem networks. This widespread propagation results in large-scale disruption of brain function and the emergence of generalised seizures. One of the significant anatomical structures facilitating this spread is the corpus callosum, a dense bundle of over 200 million axons that connects the left and right cerebral hemispheres and enables rapid synchronisation of neural activity between them. In layman’s terms, the Corpus callosum allows the hemispheres to speak to each other. To limit this propagation (spread) of epilepsy from one hemisphere to the other, neurosurgeons developed commissurotomy as a last resort intervention. By surgically severing the corpus callosum, interhemispheric transmission of abnormal electrical activity is reduced, decreasing the likelihood that seizures escalate into fully generalised events. This procedure does not cure epilepsy, but it significantly reduces seizure severity by limiting large-scale cortical synchronisation.

Between the 1940s and early 1970s, commissurotomy was performed on a small number of patients worldwide, with estimates suggesting fewer than 200 cases in total, most of them performed in the United States. The best documented research samples, including those later studied by Sperry and Gazzaniga, involved fewer than 50 patients. The procedure was reserved for individuals with extremely severe epilepsy, typically involving frequent generalised seizures occurring daily or several times per week, often accompanied by loss of consciousness, violent convulsions and repeated physical injury. At the time, there were no effective medical treatments capable of controlling this level of epilepsy. Because the operation was invasive and irreversible, it was used only as a last resort. As anti epileptic drugs became more effective from the late 1960s onwards, the clinical need for surgical separation of the hemispheres declined, and commissurotomy fell out of routine clinical use, remaining primarily of historical and research significance.

ROGER SPERRY.

ROGER SPERRY

Sperry observed that patients who had undergone commissurotomy showed surprisingly few overt impairments in everyday behaviour. In routine social interaction, they could hold conversations, follow instructions, recognise familiar people, walk, dress themselves and navigate their physical environment without apparent difficulty. Their intelligence, personality and general emotional responsiveness appeared largely intact, and there was no immediate impression of confusion or disorganisation. This apparent normality was striking because the operation had severed the corpus callosum, the brain's most significant and most crucial commissure. Containing over 200 million axons, the corpus callosum enables the typical continuous integration of sensory, motor and cognitive information between the left and right hemispheres. The fact that patients could function so competently in daily life despite the loss of this massive interhemispheric connection raised fundamental questions about how much the hemispheres typically share information, and whether unified behaviour and consciousness depend on constant communication between them

Some textbook accounts misleadingly suggest that Sperry’s primary discovery was the function of the right hemisphere. This is not accurate. By the time Sperry began his work, the general roles of the left and right hemispheres were already primarily understood through lesion, ablation and neuropsychological studies.

Thus, psychologists and neurologists already accepted the principle of hemispheric lateralisation, also described as functional asymmetry, e.g/, the idea that some cognitive and perceptual functions are lateralised, meaning they are predominantly controlled by either the left or the right cerebral hemisphere, rather than being bilaterally organised, where both hemispheres contribute equally to the same function. Lesion and ablation studies from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries played a central role in establishing this distinction. When damage occurred to specific regions of the left or right hemisphere, predictable and selective deficits were observed, indicating that the hemispheres were not functionally identical.

These studies showed that some functions, such as basic sensory processing and motor control, are largely bilateral, with both hemispheres contributing in parallel. In contrast, higher-order cognitive functions often showed explicit hemispheric specialisation. Damage to the left hemisphere was associated with impairments in language production and comprehension, while damage to the right hemisphere more commonly disrupted visuospatial processing, spatial attention and the organisation of visual information. Later experimental and neuropsychological work, including early research that informed models of working memory in the 1960s and 1970s, reinforced this view by demonstrating that verbal and visuospatial information are processed differently and rely on partially distinct neural systems, with verbal working memory showing a left hemisphere bias and visuospatial working memory showing a right hemisphere bias.

Together, these findings established that the brain is neither fully bilateral nor fully specialised, but asymmetrically organised, with specific functions distributed across both hemispheres and others showing clear lateralisation. This existing framework of hemispheric asymmetry provided the essential background for Sperry’s investigation into what happens when communication between the two hemispheres is physically severed.

To summarise, Sperry’s contribution was not the discovery of proper hemisphere function per se, but the demonstration of how the two hemispheres operate when interhemispheric communication is removed. Because what remained unknown was the extent to which the hemispheres depend on one another to produce a unified conscious experience. Specifically, it was unclear whether severing the corpus callosum would result in independent streams of consciousness, such as a visual stream associated with the right hemisphere and a verbal stream associated with the left hemisphere, operating in parallel but without integration. Alternatively, consciousness might remain centralised or unified despite the physical separation of the hemispheres.

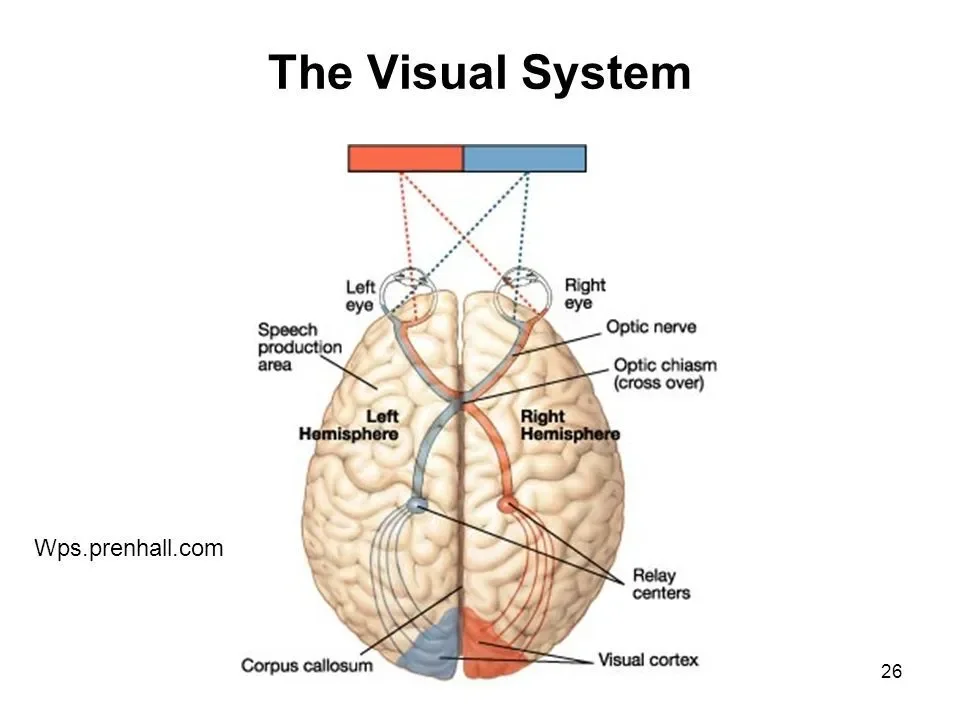

PERCEPTION IS LATERALISED, BUT VISION ISN’T

Sperry aimed to test interhemispheric communication. However, severing the internal connections between the hemispheres did not mean that sensory information from the eyes or ears was automatically segregated before entering the brain. The problem Sperry faced was that, even in split-brain patients, sensory input itself remains intact and shared across hemispheres.

Vision illustrates this clearly. Visual input is organised by visual fields rather than by the eyes. Each eye receives information from both the left and right sides of the visual environment. The left eye does not see only the left side of space, nor does the right eye see only the right side. Instead, each eye receives a partially overlapping view of the environment. This means that presenting a stimulus to one eye would not isolate hemispheric processing, because both hemispheres could still receive the information at the input stage.

This is because the eyes are described as ipsilateral: each eye receives information from both sides of the visual environment rather than from only one.

This is because visual space is divided into left and right visual fields, not left and right eyes. Each visual field is projected onto both eyes simultaneously, but onto different halves of the retina. Light from the left visual field falls on the right side of the retina in each eye, while light from the right visual field falls on the left side of the retina in each eye. As a result, neither eye corresponds to a single hemisphere or a single side of space.

In practical terms, this means that the left eye does not see only the left side of the visual field, and the right eye does not see only the right side. Instead, both eyes receive partially overlapping information from both visual fields. This ipsilateral organisation at the level of the eyes enables binocular vision, depth perception, and a unified visual scene. Still, it also means that presenting a stimulus to one eye alone does not isolate processing to one hemisphere.

Only after visual information leaves the retina does hemispheric separation occur. At the optic chiasm, fibres from the nasal half of each retina cross to the opposite hemisphere, while fibres from the temporal half remain on the same side. This is why hemispheric isolation depends on controlling visual-field location, not on the eye of presentation.

THE DIVIDED FIELD TECHNIQUE

This created a methodological problem for Sperry. If both hemispheres typically receive the same sensory information, then differences in response cannot be attributed to differences in hemispheric processing. To overcome this, Sperry needed a way to deliver sensory information to one hemisphere only, despite intact sensory organs.

He solved this problem by developing experimental techniques that exploited the organisation of sensory pathways after sensory input but before cortical integration. In vision, this took the form of the divided field technique. Participants were instructed to fixate on a central point and not move their eyes, while visual stimuli were flashed briefly to the left or right of the fixation point, typically for less than 0.1 s. This brief presentation prevented eye movements that would otherwise allow the stimulus to fall across both visual fields.

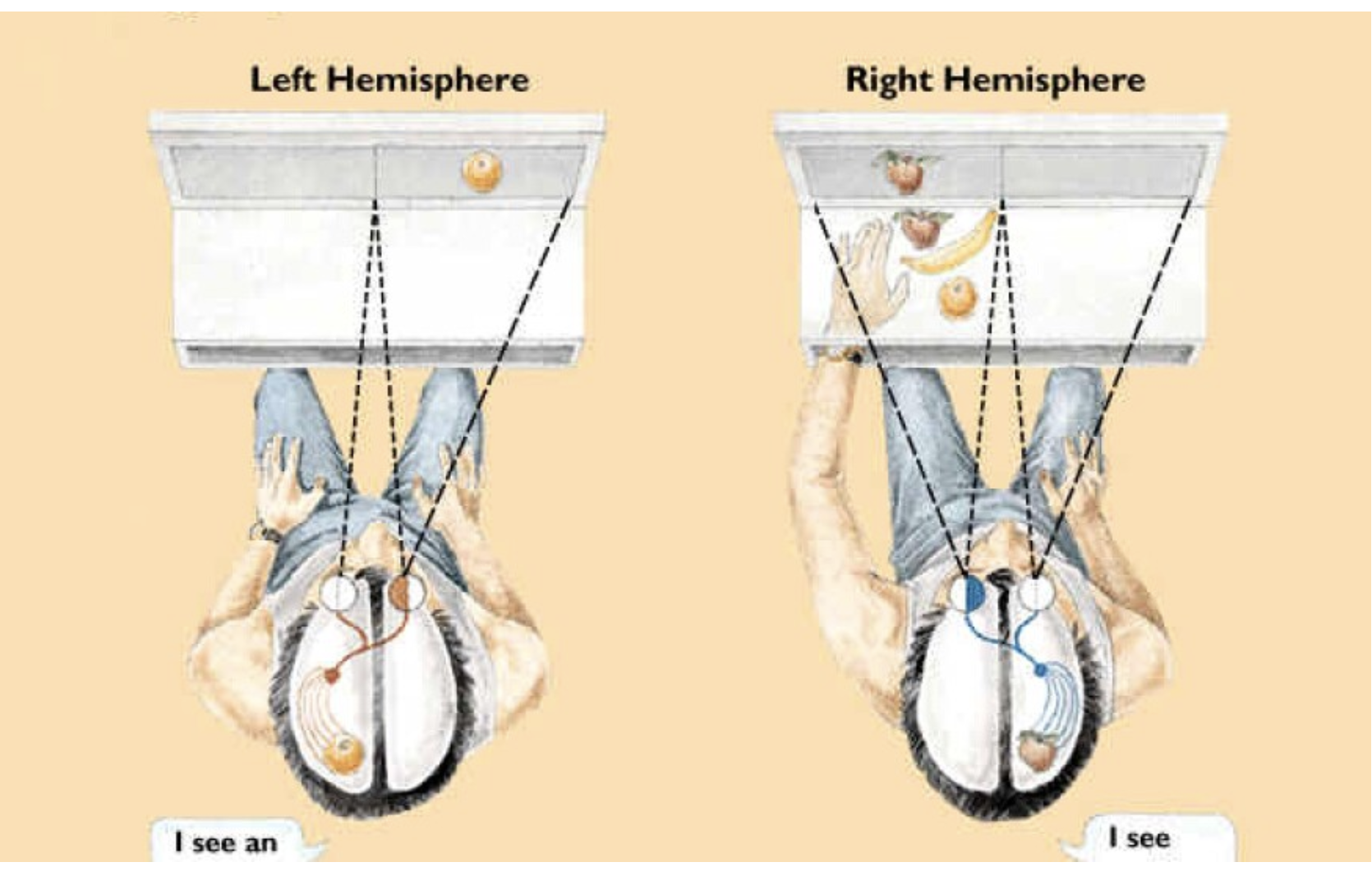

Because visual pathways are organised by visual field rather than by eye, a stimulus presented to the right visual field of the environment is projected to the left hemisphere of the brain, and a stimulus presented to the left visual field is projected to the right hemisphere. Importantly, this occurs even when both eyes are open and functioning normally, because each eye receives information from both hemispheres of visual space. By controlling the stimulus's position relative to fixation, Sperry could determine which hemisphere initially received the visual information. In split-brain patients, where the corpus callosum had been severed, this information could not be transferred to the opposite hemisphere, meaning that processing was confined to the hemisphere that first received the input.

SPERRY’S CONTROLLED OBSERVATIONS

n the period immediately following surgery, some patients showed striking behavioural conflicts. There are reports of patients attempting to perform incompatible actions simultaneously, such as pulling clothing up with one hand while pulling it down with the other, or one hand acting aggressively while the other intervened. These episodes reflected a temporary loss of coordination between hemispheres rather than stable dual control, and they typically diminished over time.

Despite this initial disruption, most split-brain patients rapidly regained functional stability. Within weeks or months, they were often difficult to distinguish from neurologically typical individuals in everyday life. Importantly, patients also reported a restored sense of personal unity. Subjectively, they experienced themselves as a single, coherent individual, even though experimental testing could still reveal hemispheric dissociations.

Working with his graduate student, Michael Gazzaniga, Sperry invited several of the "split-brain" patients to participate in his study to determine whether the surgery affected their functioning. These tests were designed to test the patients' language, vision, and motor skills.

The divided field technique refers solely to the method Sperry used to control which hemisphere initially received visual information. It involved presenting stimuli for a very brief duration to either the left or right visual hemifield while the participant fixated on a central point, thereby preventing eye movements. Because of the organisation of the visual pathways, the left hemisphere processed stimuli presented to the right visual field, and the right hemisphere processed stimuli presented to the left visual field. In split-brain patients, where the corpus callosum had been severed, information delivered to one hemisphere could not be transferred to the other. The technique itself does nothing more than deliver sensory input to a single hemisphere.

Sperry intended to present the same types of sensory material to both hemispheres, to observe how each hemisphere processed that material when it could not be shared across the corpus callosum. Using the divided-field technique, he presented words to the left and right visual fields and likewise presented pictures and objects to both visual fields. This ensured that each hemisphere received identical input categories under controlled conditions, allowing direct comparison of hemispheric processing rather than confounding differences in stimulus type.

For example, when a word was presented to the right visual field, it was processed by the left hemisphere, which contains the neural systems necessary for language production. When the same word was presented to the left visual field, it was processed by the right hemisphere. At the time, it was not known whether the right hemisphere could recognise words in any meaningful way, or whether word perception itself depended on access to left hemisphere language systems. Presenting the same verbal material to both hemispheres allowed Sperry to test this directly.

The same logic applies to pictorial and spatial material. Pictures and objects were presented to both visual hemifields for processing by either the left or the right hemisphere. While it was already suspected that visuospatial processing was biased toward the right hemisphere, Sperry’s design allowed him to examine whether the left hemisphere could process pictorial material when isolated, and whether any differences emerged depending on which hemisphere initially received the stimulus.

Crucially, Sperry recognised that responses to sensory stimuli are themselves lateralised. The left hemisphere primarily controls speech, whereas actions such as drawing, pointing, or picking up an object by touch are primarily controlled by the hemisphere opposite the hand used for the action. This meant that how participants were asked to respond was as important as what they were shown. A failure to produce a verbal response did not necessarily indicate a failure of perception. Still, it could instead reflect a mismatch between the hemisphere that perceived the stimulus and the hemisphere responsible for speech production.

By requiring different response forms, such as speaking, drawing, or selecting an object by touch, Sperry could determine whether information processed by one hemisphere could be expressed through the output systems available to that hemisphere. In this way, he revealed dissociations among perception, comprehension, and response, and identified cases in which sensory information was clearly processed but could not be expressed verbally. This approach allowed Sperry to uncover not only hemispheric differences in processing but also the limits of interhemispheric integration when the cerebral hemispheres were functionally disconnected.

Sperry applied the same principle to audition, using dichotic listening techniques in which different auditory stimuli were presented to each ear simultaneously. Because auditory pathways are predominantly contralateral, sounds presented to the right ear were processed mainly by the left hemisphere. In contrast, sounds presented to the left ear were processed mainly by the right hemisphere. In patients with split-brain, the absence of interhemispheric transfer meant that each hemisphere processed auditory input independently. By comparing verbal reports and behavioural responses, Sperry examined hemispheric differences in auditory perception using the same logic of controlled sensory entry.

Together, these techniques enabled Sperry to isolate hemispheric processing without interfering with the sensory organs themselves, thereby allowing direct testing of hemispheric independence and interhemispheric communication under controlled experimental conditions.

Make it stand out

,

RESULTS OF SPERRY’S SPLIT-BRAIN STUDIES

When words were presented to the right visual field, they were processed by the left hemisphere. Under these conditions, split-brain patients were able to report seeing the word, reading it aloud, or describing it accurately. This was expected, as the left hemisphere contains the primary language centres responsible for speech production.

However, when the exact words were presented to the left visual field, they were processed by the right hemisphere. In this case, patients typically reported that they had not observed anything. The verbal report alone suggested that the right hemisphere could not process written language. Based on these early findings, Sperry initially concluded that only the left hemisphere was capable of language, at least in terms of speech.

Crucially, Sperry subsequently demonstrated that this conclusion was incomplete. In a follow-up experiment, he tested whether the right hemisphere could understand words without being able to articulate them. Patients were asked to place their left hand (controlled by the right hemisphere) into a tray of objects hidden from view by a screen. A word was then presented to the left visual field, thereby processing it only by the right hemisphere. The word referred to one of the objects in the tray.

Although patients again verbally denied having seen any word, their left hand reliably selected the correct object from the tray. This demonstrated that the right hemisphere had recognised and understood the word, even though the patient could not say so. When asked why they were holding the object, patients were unable to explain their rationale, often expressing confusion or surprise.

These findings showed an apparent dissociation between verbal report and non-verbal behaviour. The right hemisphere processed written language at a basic level and used this information to guide action, but it lacked the capacity to produce speech. At the same time, the left hemisphere, which could speak, had not received the information and therefore could not explain the behaviour.

Overall, Sperry’s results demonstrated that the two hemispheres can process information independently, and that the ability to verbalise experience depends on which hemisphere receives the information. The findings also showed that a lack of verbal report does not necessarily indicate a lack of perception or understanding, fundamentally challenging the assumption that consciousness and awareness are always unified and accessible through language.

SPERRY'S SPLIT-BRAIN RESEARCH

APFC AIMS:

Sperry realised that ‘split-brain’ patients offered researchers an opportunity to study the functions of the two hemispheres in ways that would not be possible with accurate experimental methods.

To study the psychological effects of hemispheric disconnection in split-brain patients, and to use the results to understand how the right and left hemispheres work in “normal” people. In other words, to demonstrate that hemispheres have different functions/abilities and that each hemisphere may have its own conscious awareness & memory.

METHOD:

DESIGN: A natural experiment.

PARTICIPANTS:

11 male patients who had undergone surgery because of epilepsy.

All had a history of severe epilepsy, which had not responded to drug treatment.

Two had been operated on to sever the corpus callosum long before the experiment.

Nine had undergone surgery recently.

PROCEDURE:

Sperry designed an apparatus that allowed information to be sent to a single hemisphere to assess its capabilities; this is known as the divided field technique. The subject has one eye covered and gazes at a fixation point on an upright translucent screen (tachistoscope).

VISUAL STIMULI TESTS:

Slides have been projected on either side (or both) of the fixation point at a rate of one picture per 1/10 seconds.

PP’S have to say or write what they have seen.

RESULTS:

VISUAL STIMULI:

When an object is displayed in the right visual field (thus processed in the left hemisphere), participants can describe it in speech and writing

When an object is displayed in the left visual field (thus processed in the right hemisphere), Ps can only draw it; if asked to use the left hand to point to a matching object on the table, they can do so while still insisting that nothing was seen.

SPERRY’S CONCLUSIONS:

*Tests imply that two hemispheres have different abilities & functions. Sperry: Results. Images & objects are only recognised when presented to the same eye or hand. When an object is displayed on one half of the screen (i.e., the left) and then on the other, the P has no recollection of having seen it before. Is this evidence for two separate?

TACTILE STIMULI TESTS:

Objects are presented to the left or right hand (or both) behind the screen. PP’S must point, feel, or draw objects (with left hand).

Tests to the Right hemisphere: Range of tests/puzzles.

RESULTS TACTILE STIMULI:

Objects placed in the right hand: PP’s described the object in speech and writing.

Objects placed in the left hand: Ps made wild guesses - seemed unaware of the object in their hand, but could draw, point, or select an object by touch • When objects were placed in one hand, subjects could point to the object with the same hand.

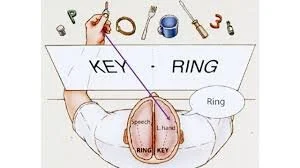

RESULTS WHEN TWO DIFFERENT OBJECTS ARE DISPLAYED SIMULTANEOUSLY: • E.G. KEY & RING

Ps were asked to draw with their left hand what they saw on the left half of the screen (KEY). But said they had drawn what was on the right half of the screen (RING) implies that one side of the brain was unaware of what the other side had.

RESULTS • EXTRA TESTS TO RIGHT HEMISPHERE:

Can carry out simple maths problems.

Can sort objects by size, shape, & texture.

Picture of nude presented amongst geometric shapes produces giggling & blushing, but PP’S have no awareness of seeing pictures.

CONCLUSIONS:

Hemispheres have different functions: only the left can produce language.

The right hemisphere can recall & identify stimuli but cannot verbalise this.

Hemispheres have independent perception, awareness & memory.

SUMMARY The LEFT HEMISPHERE (LH)

In right-handed people and most left-handed people, the left hemisphere specialises in speech and writing and in the organisation of language.

The left hemisphere can process visual information from the right visual hemifield and somatosensory input from the right half of the body.

SUMMARY The RIGHT HEMISPHERE (RH)

The RH is mute and cannot speak or write (aphasic and agraphic. It can understand and read some basic, concrete nouns. It can process visual information and nonverbal communication, including intonation and facial expressions.

But can non-verbally indicate that mental processes centred on the left visual field and the left half of the body are present.

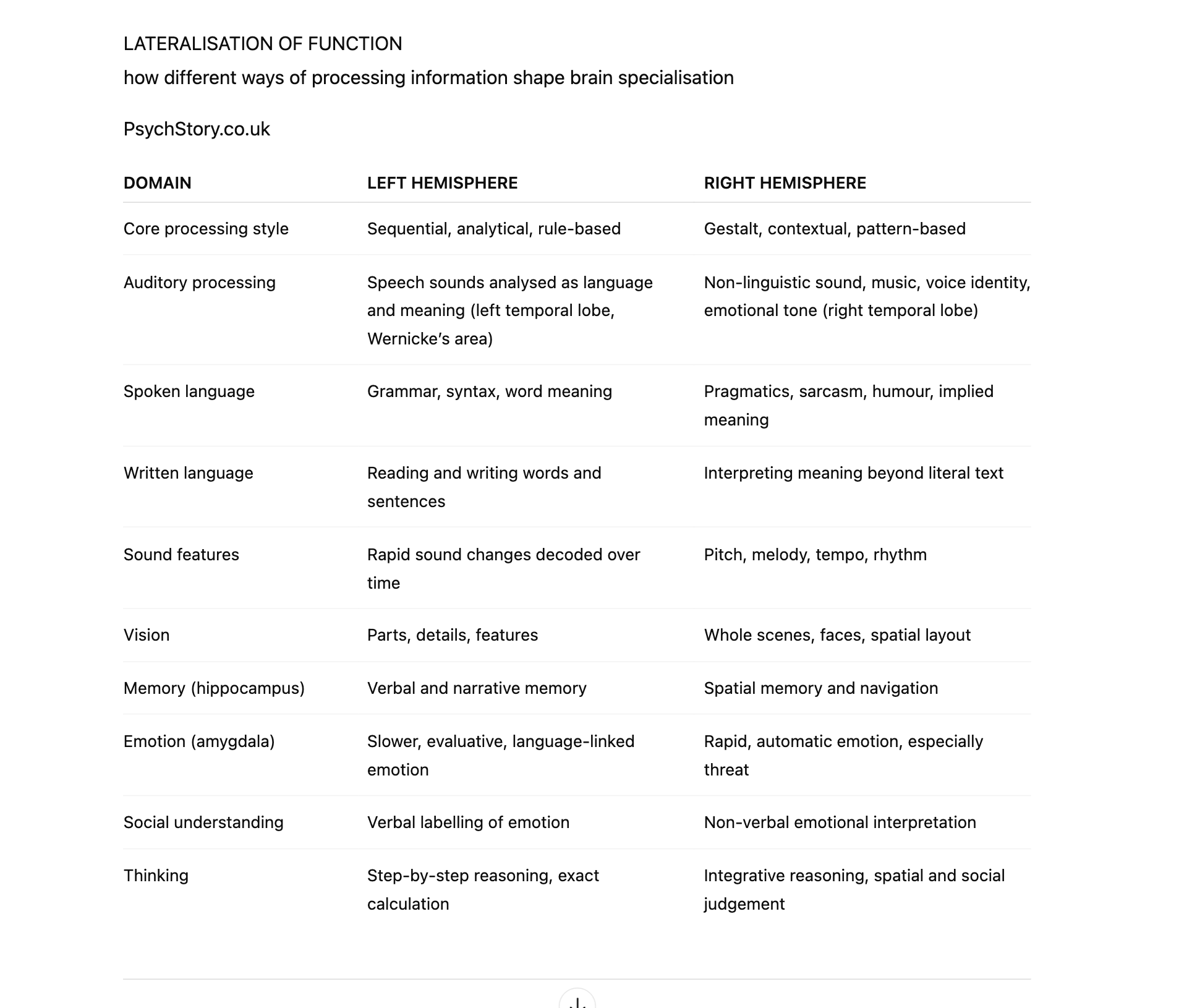

SUGGESTED CHARACTERISTICS OF THE TWO CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES

The two cerebral hemispheres differ in their processing biases, not in intelligence, personality, or ability. These differences reflect a division of labour that improves perceptual and cognitive efficiency. Neither hemisphere works in isolation, and most complex behaviour depends on their interaction.

The left hemisphere shows a bias toward verbal and symbolic processing. It plays a primary role in speech production, reading, and writing, as well as in the use of language as a rule-governed system, including grammar and syntax. Its mode of processing is typically sequential and analytic, breaking information into smaller components and processing them sequentially. This makes the left hemisphere particularly suited to tasks involving logic, mathematics, and formal reasoning, where order and precision are essential. In visual processing, the left hemisphere is biased toward fine detail and local features, contributing to object recognition that relies on identifying specific parts rather than overall form.

The right hemisphere shows a bias toward global, holistic (gestalt) processing. It integrates information across space and time to form coherent wholes, rather than analysing elements in isolation. This makes it especially important for visuospatial processing, including spatial awareness, mental rotation, and face recognition, which rely on the configuration of features rather than on individual details (supported by areas such as the fusiform face area). The right hemisphere is also more involved in processing the emotional and prosodic aspects of language, such as intonation, rhythm, and emphasis, as well as nonverbal communication, such as facial expressions and gestures.

In terms of thinking style, the left hemisphere tends toward convergent processing, narrowing possibilities to arrive at a single correct answer, as is typical in arithmetic or logical problem-solving. The right hemisphere is more associated with divergent processing, generating multiple possibilities and interpretations, which supports creativity, metaphor, and insight. This does not mean that the left hemisphere is “scientific” and the right hemisphere “artistic” in any absolute sense; instead, scientific reasoning often relies on left-hemisphere analytical structure, while artistic expression often relies on right-hemisphere holistic and emotional integration. In practice, both science and art require contributions from both hemispheres.

Overall, the hemispheres differ not in what they are capable of, but in how they process information. The left hemisphere prioritises detail, order, and symbolic structure, while the right hemisphere prioritises form, context, and meaning. Normal cognition depends on the continuous interaction between these complementary processing styles.

LEFT-HEMISPHERE

Verbal/ language-based: speech, reading and writing.

Visual-spatial, face recognition (Fusiform facial area), pattern and object recognition

Sequential processing

Simultaneous, parallel processing

Analytical

RIGHT-HEMISPHERE

Gestalt and Holistic

Rational

Emotional

Divergent

Intuitive, creative

Convergent Thought

Divergent thought.

Scientific

Artistic

EVALUATION OF SPERRY’S SPLIT BRAIN EXPERIMENTS

LIMITATIONS

SMALL AND UNREPRESENTATIVE SAMPLE

Commissurotomy is an extreme and now rarely performed procedure, resulting in a very limited available sample. Fewer than 80 individuals have undergone the operation, and only a small subset—often fewer than 20—have been studied in controlled psychological experiments, with much of the evidence based on fewer than 10 patients who were extensively tested. This makes it challenging to generalise findings from split-brain research to the broader population, as the results may reflect the unique neurological and clinical characteristics of these individuals rather than typical hemispheric organisation.

NORMALITY OF PARTICIPANTS?

Split-brain patients cannot be considered neurologically typical before surgery. Severe epilepsy is itself associated with abnormal neural activity and long-term changes in brain organisation, and patients often live with the condition for many years before commissurotomy is considered. In addition, most patients were receiving prolonged drug therapy, which may also have affected brain function. It is therefore difficult to separate the effects of hemisphere disconnection from pre-existing neurological abnormalities.

There is also evidence that some split-brain patients showed atypical hemispheric organisation even before surgery. For example, a minority exhibited right-hemisphere language, as indicated by left-hand writing, whereas others showed bilateral language representation, with language processing distributed across both hemispheres. These atypical patterns suggest that the brains of patients with split-brain may not reflect the organisation observed in the majority of the population.

As a result, findings from split-brain research are difficult to generalise to neurotypical individuals, particularly those with the typical pattern of left-hemisphere language dominance, which is present in over 95% of the population.

UNCONTROLLABLE VARIABLES

The split-brain sample cannot be treated as a homogeneous group because substantial uncontrolled differences existed among participants. Patients varied widely in age, gender, age of onset of epilepsy, underlying causes of epilepsy, age at which commissurotomy was performed, and age at which they were tested. Each of these factors could independently affect brain organisation and cognitive performance, making it difficult to attribute observed differences solely to hemispheric disconnection.

In addition, evidence indicates that the human corpus callosum exhibits sex-related anatomical variation. Some studies suggest that the posterior region of the corpus callosum (the splenium) is proportionally larger in females. At the same time, earlier postmortem data indicate that males, on average, have larger brains and larger corpus callosa. These anatomical differences introduce further variability into the sample and complicate the interpretation of findings.

Taken together, this level of uncontrolled variation weakens the reliability of split-brain findings. It limits the extent to which conclusions about hemispheric lateralisation can be generalised to the broader population.

EVALUATION OF RESEARCH

For the reasons outlined earlier, findings from patients with split-brain alone cannot be used to construct models of the neurotypical brain. However, evidence for hemispheric lateralisation does not rest solely on commissurotomy research.

Alongside split-brain studies, a large body of research has examined neurologically typical participants, primarily using divided-field paradigms and dichotic listening. These methods were explicitly designed to investigate hemispheric processing in intact brains, where interhemispheric transfer via the corpus callosum is rapid. By presenting competing stimuli briefly and simultaneously to each visual hemifield or auditory ear, researchers demonstrated consistent hemispheric biases without surgical intervention. Although the observed effects are weaker than those observed in patients with split-brain, they are reliable across large samples, thereby increasing external validity.

More recently, neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI and PET have provided converging evidence for hemispheric lateralisation. These studies consistently show left-hemisphere dominance for language processing and right-hemisphere dominance for visuospatial processing in the majority of the population, typically over 95%. Unlike case studies, neuroimaging enables examination of lateralisation in large, representative samples, thereby strengthening generalisability.

Additional support comes from case studies of focal brain damage caused by strokes, tumours, head injuries, and neurological disease. Across many unrelated cases, damage to the left hemisphere disproportionately affects language, while damage to the right hemisphere more often disrupts visuospatial processing, emotional prosody, and face recognition. The consistency of these patterns across different causes of damage supports hemispheric specialisation beyond split-brain research.

However, lateralisation is not universal. A minority of individuals exhibit atypical organisation, including left-handers with reversed hemispheric dominance and individuals with bilateral language representation. These variations indicate that lateralisation reflects population-level tendencies rather than fixed rules, and they may influence aspects of cognition, including self-awareness and resilience to brain injury.

Overall, while split-brain studies were methodologically limited, evidence from experimental studies in healthy participants, neuroimaging, and focal brain damage provides strong, converging support for hemispheric lateralisation in the neurotypical brain.

STRENGTHS

DISCOVERIES ABOUT COGNITIVE FUNCTIONS OF THE RIGHT HEMISPHERE

Sperry’s split-brain research demonstrated that the right hemisphere possesses distinct and essential cognitive functions, rather than being a passive or inferior counterpart to the left hemisphere. Before this work, dominant models of brain function placed disproportionate emphasis on the left hemisphere, largely because of its role in language, analytical reasoning, and learned motor skills. As a result, the right hemisphere was often regarded as limited in cognitive capacity.

Sperry’s findings challenged this view. Although the right hemisphere lacks fluent speech production, it is highly specialised for visuospatial processing, including face recognition, spatial relationships, and complex visual patterns. It can also comprehend visual information, respond appropriately to environmental cues, and guide behaviour in meaningful ways, even when it cannot articulate those responses verbally.

Importantly, Sperry showed that the absence of speech does not imply an absence of understanding or awareness. The right hemisphere is capable of processing information, forming representations, and supporting conscious experience, even when that experience cannot be expressed in words. His work, therefore, shifted scientific understanding away from a hierarchy of hemispheres toward a model of complementary specialisation, in which each hemisphere contributes different but equally important forms of cognition.

THE ROLE OF LANGUAGE AND CONSCIOUSNESS

The inability of these participants to verbalise a thought or feeling that is represented elsewhere in the brain suggests that consciousness is not required for task performance.

Valid criticism is that this interrupts signals to the language centres, which are not necessarily conscious. However, there is an implicit assumption that our sense of consciousness is perceived internally through language. This raises the difficult question of what constitutes consciousness. Can there be consciousness without language?

We are used to interpreting consciousness with language, but can we say that communicating through a drawn image indicates consciousness? Alternatively, is the ability to draw a picture based on a visual cue something that can happen unconsciously, without the need for consciousness? Perhaps even language perception and vocalisation occur primarily at an unconscious level, despite our sense that they are intimately tied to consciousness.

Sperry’s split-brain research had its most significant implications for the nature of conscious awareness, specifically for the roles that language and interhemispheric integration play in making mental content consciously available to the individual.

In split-brain patients, a consistent asymmetry emerged when participants were asked to reflect on their own mental states. Verbal reports of awareness came exclusively from the left hemisphere. When patients were asked how they felt, what they thought, or what they had perceived, their answers reflected only information available to the left hemisphere. Although the right hemisphere could process visual information, recognise patterns, and guide behaviour, these processes were not experienced by the person as conscious mental content.

This finding does not imply that the right hemisphere is “conscious in its own way” in any equivalent sense. Sperry did not argue for two parallel, equally valid consciousnesses. Instead, his findings showed that conscious awareness, as humans experience it, depends on integration with language-mediated systems, which are typically left-lateralised. Without access to these systems, right-hemisphere activity does not enter conscious awareness, even though it can influence behaviour.

The critical structure here is the corpus callosum. In the intact brain, the corpus callosum enables information processed in the right hemisphere to be transferred to the left hemisphere, where it can be labelled, reflected upon, and incorporated into conscious experience. This is why we can be aware of our own visual-spatial abilities, emotional responses, and intuitions. When the corpus callosum is severed, this mechanism fails. Right-hemisphere activity remains functionally effective but phenomenologically inaccessible. It operates outside awareness rather than alongside it.

This places right-hemisphere processing closer to what would properly be described as subconscious or pre-conscious, rather than conscious in its own right. The right hemisphere can detect patterns, complete visual information, and generate responses without those processes being experienced consciously by the individual. For example, a patient with a split brain may draw an image correctly using right-hemisphere processing without knowing why. The act is purposeful, but the purpose is not consciously known.

This interpretation avoids the misleading conclusion that split-brain patients possess two independent consciousnesses. Instead, it shows that conscious awareness requires a specific neural architecture, one in which information is not only processed but also made available to the systems that support reflection, self-report, and narrative identity. The corpus callosum is therefore not merely a communication pathway, but a realisation mechanism for consciousness.

A common criticism of this position appeals to individuals who lack spoken language, such as congenitally deaf people, suggesting that if consciousness depends on language, such individuals would lack awareness. This objection misunderstands the role of language in Sperry’s framework. Language need not be auditory or spoken to support consciousness. It is a symbolic coding system rather than a sound-based one.

Neuroimaging studies show that sign language is processed predominantly in the left hemisphere, using the same language networks as spoken and written language. Although sign language is visual in form, it is linguistic in structure. Deaf individuals, therefore, still engage left-hemisphere language systems to label, organise, and reflect upon experience. Their conscious awareness is not diminished; it is supported by a different sensory modality mapped onto the same symbolic architecture.

This distinction reinforces Sperry’s point rather than undermining it. Conscious awareness depends on the integration of perceptual processing with symbolic systems that allow reflection and self-reference. Right-hemisphere visual-spatial processing alone is insufficient. It must be integrated with left-hemisphere language systems to become part of the conscious self.

Sperry’s broader theoretical claim followed directly from these findings. He rejected the idea that consciousness is a passive by-product of neural activity, but he also rejected the idea that all neural processing is conscious. Instead, he argued that consciousness emerges when neural activity reaches a level of organised integration. Once present, it exerts a directive influence on behaviour by shaping attention, intention, and choice.

In this sense, Sperry’s work does not elevate right-hemisphere processing to equal conscious status, nor does it deny its importance. Rather, it clarifies the conditions under which mental activity becomes consciously realised. Consciousness is not everywhere in the brain, nor is it reducible to raw processing. It is an emergent property of integrated neural systems, and the corpus callosum is central to that integration

MIND OVER MATTER

The implications of split-brain research extend far beyond hemispheric specialisation and reach directly into the long-standing debate about the relationship between mind and brain. For much of the twentieth century, the dominant position in neuroscience and psychology was that the brain operates according to purely physical laws and that mental states such as thoughts, intentions, and conscious awareness are secondary by-products of neural activity. Under this view, behaviour can in principle be explained entirely by neural mechanisms, with consciousness playing little or no causal role.

Some scientists interpreted Sperry’s findings as supporting this mechanistic picture. If behaviour can be initiated, guided, and completed by neural processes that never enter conscious awareness, then consciousness might appear redundant. Reasoning, decision-making, and even complex actions could be understood as outputs of neural circuitry, with conscious experience merely accompanying these processes rather than influencing them.

Sperry rejected this conclusion. He argued that although neural activity is necessary for consciousness, it is not sufficient to explain behaviour at the level at which humans actually act. Conscious awareness, in his view, is not an epiphenomenon that floats passively above brain activity, nor is it an illusion produced by neural machinery. Instead, it is an emergent property of organised brain activity that plays a functional role in directing behaviour.

Sperry’s position was that conscious mental states operate at a higher level of organisation than individual neurons or synapses. While they do not violate physical laws or intervene in neural processes from outside the system, they exert influence by shaping the overall pattern of neural activity. In this sense, consciousness constrains and guides what the brain does next, rather than merely reflecting what it has already done.

This view challenged both strict reductionism and classical dualism. Sperry did not claim that the mind exists independently of the brain, nor that it acts as a separate substance. At the same time, he denied that mental events can be eliminated from scientific explanation. For Sperry, conscious intentions, values, and goals are real features of brain organisation that influence behaviour precisely because they arise from the coordinated activity of large neural systems.

The phrase “mind over matter”, therefore, does not imply that consciousness overrides or dominates the brain. Instead, it captures Sperry’s claim that mental states have causal relevance within the brain's physical system. Just as higher-level properties in biological systems can influence the behaviour of their components, conscious awareness can influence the direction and organisation of neural activity without breaking the rules of neurophysiology.

This position had essential implications for concepts such as free will, responsibility, and human values. If consciousness can shape behaviour, then human actions cannot be fully explained by neural mechanisms alone. Sperry argued that ignoring conscious experience yields an incomplete account of behaviour, failing to capture how humans plan, deliberate, and act with purpose.

In this way, Sperry’s work reopened questions that many scientists had set aside as unscientific. Rather than treating consciousness as a philosophical afterthought, he insisted that it must be incorporated into explanations of brain function. His contribution was not to provide a final solution to the mind–body problem, but to show that any adequate account of human behaviour must take conscious awareness seriously as part of the causal story

SPERRY’S DIVIDED-FIELD TECHNIQUE

Sperry’s divided-field technique was vital because it provided a controlled method for exposing hemispheric differences without causing brain damage. By selectively routing information to one hemisphere, it showed that processing, awareness, and verbal report can dissociate, and that hemispheric specialisation is revealed by limits on access rather than by loss of ability. The technique became foundational because it allowed lateralisation to be studied as a property of information flow and integration, rather than crude localisation.