NEURAL CORRELATES AND THE DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS

WHAT ARE NEURAL CORRELATES?

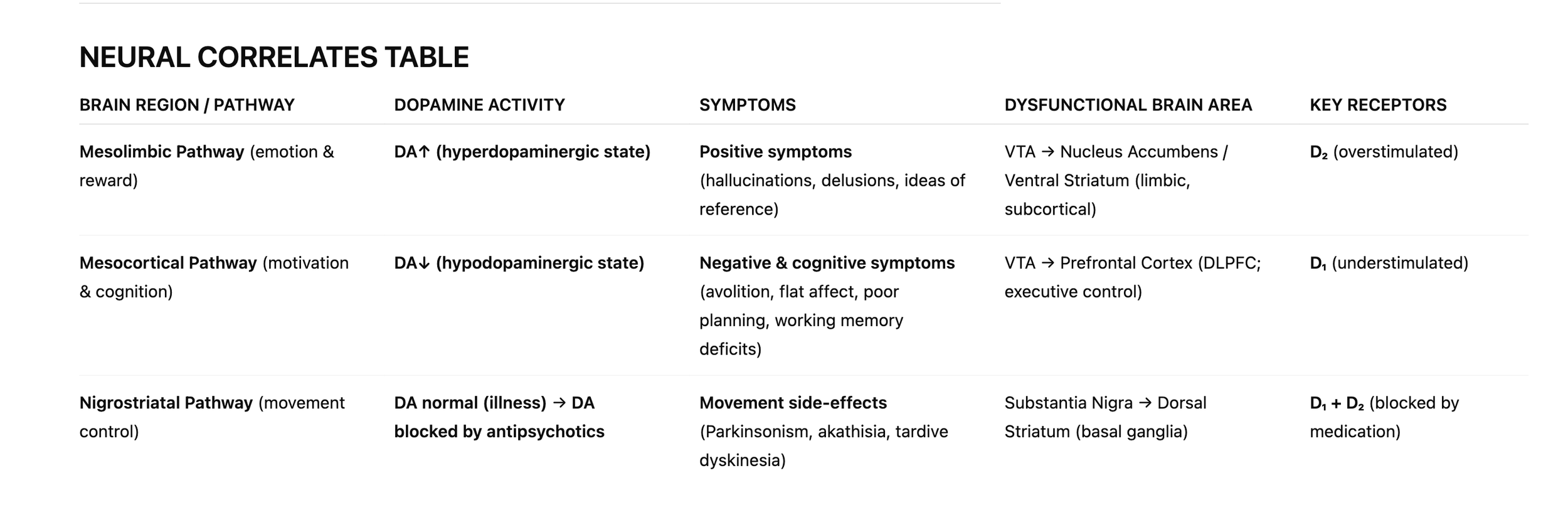

A neural correlate is a change in brain activity, function, or structure that is consistently linked to a specific behaviour or mental state. Genes, disease, epigenetic factors, or environmental influences may cause these differences. For example, people who have difficulty producing speech often show damage to a region in the left frontal lobe known as Broca’s area. This suggests a strong relationship between that brain region and speech output. In clinical psychology, neural correlates are used to identify biological features of mental illness by linking brain abnormalities with patterns of symptoms. While correlations alone do not prove cause and effect, in many cases — especially where brain damage leads to an apparent behavioural change — a causal relationship is strongly supported by converging evidence. A neural correlate for schizophrenia is a physical difference in the brain that is linked to the symptoms of the disorder. It refers to specific, observable features in brain structure or activity that consistently occur in people with schizophrenia. Research has identified many neural correlates for schizophrenia, meaning areas of brain damage or differences that correspond with schizophrenic behaviour. However, because this is a large area, AQA requires you to focus on the dopamine hypothesis as the neural correlate to discuss in your essay. The best-established neural correlate of positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions) is excess dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway that overstimulates D2 receptors. At the same time, too little dopamine reaching the prefrontal cortex (mesocortical hypo-dopaminergia) is the main biological driver of negative and cognitive symptoms such as avolition, flat affect, and speech poverty. Together, these opposite imbalances in different brain pathways form the modern dopamine hypothesis and remain the single most crucial biochemical explanation for schizophrenia.

PLEASE NOTE:

Biochemical theories do not compete with genetic theories. They can be complementary; for example, genes could cause a person to have hypodopaminergic or hyperdopaminergic systems.

This topic focuses on the dopamine hypothesis as the primary example of neural correlates. That said, it is vital to be aware that dopamine is not the only neural correlate of schizophrenia. For example, research has found that people with schizophrenia often have enlarged brain ventricles. These are fluid-filled spaces in the brain, and their enlargement suggests a loss of brain tissue linked to negative symptoms and cognitive impairment. While this is a well-documented neural correlate, neither this nor other neural correlates are discussed at length in this thread.

BACKGROUND TO THE DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS

BACKGROUND TO THE DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS: PHENOTHIAZINE, ANTIHISTAMINES AND SURGICAL SHOCK (1940s–1950s)In the late 1940s, French surgeon Henri Laborit was testing drugs to prevent surgical shock. He tried a new antihistamine called promethazine. Promethazine belongs to a chemical family known as phenothiazines – a group of synthetic compounds built around a three-ring structure containing sulphur and nitrogen. At the time, chemists were using this phenothiazine “scaffold” only to make antihistamines for allergies and nausea; nobody suspected it could affect the brain. Laborit gave promethazine to stabilise blood pressure during operations. It worked, but he noticed something completely unexpected: patients became unusually calm and emotionally detached, yet remained fully awake and able to answer questions typically.

No existing drug had ever produced this kind of mental tranquillity without causing drowsiness or dullness. This accidental discovery led the pharmaceutical company Rhône-Poulenc to make a closely related phenothiazine compound in 1950. They called it RP-4560 and later renamed it chlorpromazine. Laborit used it first in anaesthesia and saw that the calming effects were even more potent than with promethazine. Word quickly reached psychiatrists Jean Delay and Pierre Deniker in Paris, who were searching for a way to control extreme psychotic agitation without heavy sedation. In early 1952, they gave chlorpromazine to their most severely disturbed patients at Sainte-Anne Hospital. Hallucinations, delusions, and violent behaviour improved dramatically within days, and patients remained alert – an entirely new phenomenon.

It is worth noting that reserpine was also used during this period in an attempt to calm psychiatric patients. Although clinically unreliable, it became scientifically pivotal: Arvid Carlsson later proved that reserpine worked by depleting dopamine stores, a finding that transformed dopamine from a simple metabolic intermediate into a recognised neurotransmitter and helped shape the later dopamine hypothesis.

Chlorpromazine was launched in May 1952 (Largactil in France, soon Thorazine in the United States) and is universally recognised as the world’s first actual antipsychotic drug. The fact that it came from the same phenothiazine family as a simple antihistamine remains one of medicine’s most significant pieces of serendipity.(Everything before 1952 – barbiturates, bromides, opium derivatives, and the newly introduced reserpine – could only sedate or quiet patients, but none reliably reduced the core psychotic symptoms of hallucinations and delusions while leaving the person awake and reachable. That is why chlorpromazine was immediately seen as revolutionary.)

PSYCHIATRIC TESTING OF CHLORPROMAZINE (1951-1952)

In 1951, preliminary testing began on agitated psychiatric patients using chlorpromazine.

1952: Delay and Deniker expanded trials to schizophrenia patients at Sainte-Anne Hospital in Paris.

This discovery marked the beginning of modern pharmacological treatment for schizophrenia and established chlorpromazine as the first typical antipsychotic drug.

SUPPORT PSYCHSTORY

〰️

SUPPORT PSYCHSTORY 〰️

LINKING CHLORPROMAZINE TO SCHIZOPHENIA

When chlorpromazine (later marketed as Thorazine) was introduced in the early 1950s, it was immediately clear that it produced effects unlike traditional sedatives. Barbiturates suppressed consciousness and induced sleep, whereas chlorpromazine reduced hallucinations, delusions, and agitation while leaving patients alert. Clinicians recognised that it worked differently, that it was doing something more specific than just calming or sedating, but they had no understanding of how.At the time, the mechanisms of psychiatric drugs were a mystery. The concept of neurotransmitters was only emerging, and the role of brain chemistry in mental illness was not yet part of scientific thinking. Terms like “calming the nerves” or “reducing stimulation” were placeholders for processes no one could yet describe. Neuroscience was only emerging, and with no clear theory of the brain, observations remained disconnected from explanation.

THE DISCOVERY OF NEUROTRANSMITTERS

For most of the early 20th century, scientists believed that neurons communicated only electrically. The idea that they might also use chemical messengers was met with heavy scepticism. The first real proof came from the German pharmacologist Otto Loewi in 1921. In his famous experiment, Loewi stimulated the vagus nerve of one frog heart, collected the fluid around it, and poured that fluid onto a second heart. The second heart slowed down in the same way. He called the unknown substance “Vagusstoff”; it was soon identified as acetylcholine, the first neurotransmitter to be proven. Even after this discovery, progress was painfully slow. For the next thirty years, acetylcholine remained almost the only accepted neurotransmitter. Dopamine itself had been artificially created in the laboratory (synthesised) as early as 1910. Still, for decades, it was regarded as nothing more than a minor, biologically unimportant stepping-stone on the pathway to noradrenaline and adrenaline. Everything changed in the late 1950s with the Swedish pharmacologist Arvid Carlsson. Carlsson was studying reserpine, an ancient Indian plant remedy that Western doctors were using in the early 1950s to lower high blood pressure and to calm severely agitated psychiatric patients. Doctors had noticed that reserpine often caused profound stiffness and immobility – exactly like Parkinson’s disease. Carlsson suspected reserpine was removing a vital chemical from the brain. He gave rabbits reserpine; they became frozen entirely. He then killed the animals, removed their brains, and used a new chemical technique (fluorescence spectrophotometry) to measure the three known monoamines: noradrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine. He found that dopamine had almost completely disappeared (in some brain areas by more than 95 %), while the other two chemicals were only slightly reduced. He then injected the frozen rabbits with L-DOPA – the natural substance the body converts into dopamine. Within minutes, the animals woke up and moved perfectly normally again. Carlsson’s experiments proved once and for all that dopamine was not just a useless intermediate. It was a true neurotransmitter in its own right and essential for voluntary movement.

THE BIRTH OF THE ORIGINAL DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS

By the early 1960s, the evidence was now coming from several independent directions, all pointing to the same neurotransmitter that Arvid Carlsson had only recently proven existed: dopamine.

First, every drug that reliably reduced psychotic symptoms – chlorpromazine and the other phenothiazines, haloperidol (a completely different chemical class, synthesised in 1958), and even reserpine (the ancient Indian plant remedy that had been used since the early 1950s to calm severely agitated psychiatric patients) – shared one crucial action: they all reduced dopamine transmission in the brain.

Phenothiazines and haloperidol directly blocked dopamine receptors.

Reserpine emptied dopamine from nerve terminals (exactly what Carlsson had shown in his rabbit experiments).

The stronger the dopamine-reducing effect, the better the drug worked against hallucinations and delusions – and the more likely it was to cause the same Parkinson-like side-effects Carlsson had linked to dopamine depletion.

Second, the opposite situation was also becoming clear. Heavy amphetamine users were turning up with intense paranoia, hallucinations, and delusions that were often indistinguishable from acute paranoid schizophrenia. In the 1950s and early 1960s, researchers deliberately gave large doses of amphetamines to healthy volunteers in controlled studies; many developed a temporary but full-blown psychotic state that cleared when the drug wore off. Amphetamines were already known to work by massively increasing dopamine release and blocking its reuptake. The pattern was now unmistakable:

Increase dopamine dramatically → psychosis appears.

Reduce dopamine transmission → psychosis disappears

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia was formally proposed by Jacques van Rossum in 1966–1967, who suggested that schizophrenia was caused by dopamine dysregulation. This proposal marked a turning point in psychiatry and led to decades of research into dopamine’s role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia.

HOW DOPAMINE CONTRIBUTES TO SCHIZOPHRENIA

HOW DOPAMINE CONTRIBUTES TO SCHIZOPHRENIA

Dopamine is the brain’s primary chemical signal for salience — it flags what matters in the environment and motivates us to pay attention to it. Usually, it helps us focus on goal-relevant stimuli (food, danger, social cues) while filtering out background noise. In schizophrenia, this filtering system fails, mainly due to dopamine dysregulation, especially excess activity in the mesolimbic pathway. This excess leads to aberrant salience: neutral or trivial stimuli suddenly feel profoundly important. Random sensory input, fleeting thoughts, or coincidental events are tagged with emotional and motivational significance they do not objectively possess. The brain’s relevance detector is overactive and miscalibrated; everything competes for attention at once.

WHY DOES TOO MUCH DOPAMINE IN THE MESOLIMBIC SYSTEM CAUSE POSITIVE SYMPTOMS?

Usually, the brain has a built-in “volume knob” that keeps dopamine from getting too loud. In schizophrenia, that volume knob is broken. Too much dopamine pours out and stays in the system. All that extra dopamine lands on D2 receptors in the reward/salience parts of the brain (nucleus accumbens and limbic areas) and turns the volume up to maximum. Suddenly, everyday things — a stranger’s glance, a word on the radio, a random number plate — feel incredibly important, threatening, or personally meant for you. The brain isn’t making things up out of thin air; it’s just cranking the “THIS MATTERS!” signal way too high on completely ordinary stuff. That flood of false importance is called aberrant salience, and it’s the biological spark that lights the fire of delusions and hallucinations.

EFFECTS ON THINKING AND LANGUAGE

When the brain can no longer rank or suppress irrelevant information, thought becomes fragmented and derailed:

Loose associations (derailment): Ideas shift abruptly because a word, sound, or image momentarily hijacks attention. A conversation about the weather might suddenly veer to cats because “rain” sounded like “reign.”

Knight’s move thinking: Even less connected leaps occur — from one topic to something apparently unrelated — because multiple competing ideas feel equally urgent.

Clang associations: Speech is guided by phonology rather than meaning (rhymes, alliteration, rhythm): “The train goes insane in the rain on the plain.”

Pressure of speech and poverty of content: Rapid, tangled speech emerges as the mind tries to express everything that feels salient at once, often resulting in vague or empty phrases despite high volume.

At a deeper level, semantic integration collapses. Instead of processing language as coherent wholes, single words or syllables become hyper-significant islands of meaning, while context and logical connections fade.

HOW ABERRANT SALIENCE GIVES RISE TO DELUSIONS AND HALLUCINATIONS

The brain is a meaning-making organ. When irrelevant stimuli are flooded with significance, it attempts to explain why they feel so important. This explanatory effort produces delusions.

Delusions of reference: A song on the radio, a license plate, or a stranger’s gesture is interpreted as carrying a personal message.

Persecutory or grandiose delusions: Random events are woven into a narrative of being specially targeted, controlled, followed, or chosen.

Hallucinations, especially auditory ones, arise from a related but distinct failure: impaired source monitoring. Usually, we tag our own inner speech and spontaneous thoughts as self-generated. Excess mesolimbic dopamine, combined with reduced prefrontal control, disrupts this tagging. An idea that pops up unbidden — already made salient by dopamine — is no longer recognised as internal. It is attributed to an external agent: voices commenting, commanding, or discussing the person. If the thought feels inserted or withdrawn, it may be experienced as mind control or thought broadcasting. In essence, schizophrenia can be understood as a disorder of salience and source attribution driven by dopamine dysregulation. The world becomes overloaded with false importance, and the boundary between self and non-self breaks down. What begins as a biochemical misassignment of relevance ends as a profound restructuring of reality itself.

THE DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS AND COGNITIVE INFLAMMATION

According to psychiatrist Shitij Kapur, dopamine is a biochemical fuel that amplifies specific ways of thinking. He argues that people who develop schizophrenia tend to jump to conclusions or interpret events in extreme ways. Excess dopamine inflames these cognitive patterns, pushing them into full psychosis.

Kapur explains:

“If you could test patients before they were psychotic, you’d probably find they tend to jump to conclusions or choose extreme explanations. When you add to this a biochemical fuel – excess dopamine – you inflame this way of thinking; that is what dopamine does.”

This suggests that dopamine dysregulation does not create new ways of thinking but amplifies existing tendencies, making them far more extreme and more challenging to control.

SUMMARY

Dopamine regulates attention and motivation, helping to filter what is essential from what is not.

Excess dopamine makes everything seem meaningful, making it hard to ignore irrelevant details.

This breakdown in filtering leads to psychotic symptoms such as delusions of reference, paranoia, and auditory hallucinations.

Kapur argues that dopamine fuels pre-existing cognitive tendencies, exaggerating them rather than creating them anew.

RESEARCH FOR THE ORIGINAL DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS

If a dopamine imbalance causes schizophrenia, there should be evidence of unusual dopamine activity in the brains of individuals with the disorder. Early and contemporary studies provide both support and critique for this hypothesis. Below is a summary of the key research evidence, from historical methods to modern imaging techniques.

ANTI PSYCHOTIC DRUGS

As mentioned above, antipsychotics were discovered before the dopamine connection was made. However, once it was found that anti psychotics reduced the availability of dopamine, the primary evidence used to support the dopamine hypothesis was the success of these antipsychotic drugs; if they reduced dopamine firing, then schizophrenia must be caused by excess dopamine activity. Moreover, not only do anti-psychotic drugs (dopamine antagonists) reduce positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions) in type one schizophrenics, but when the same individuals are given drugs with a dopamine agonist, e.g., medications such as L-DOPA that increase dopamine availability, then their symptoms become much worse.

Also adding support to the drug theme is research on Parkinson’s sufferers and dopamine agonists. A lack of dopamine causes Parkinson's disease. As a result, Parkinson’s patients are treated with synthetic legal agonists to increase their dopamine availability (e.g., L-DOPA). However, if Parkinson’s patients are given high levels of L-DOPA, they can suffer from positive symptoms, e.g., they can experience psychotic side effects which mimic the symptoms of schizophrenia. Conversely, Type 1 schizophrenics can suffer from Parkinson’s symptoms when on antipsychotic drugs.

RESEARCH ILLEGAL STREET DRUGS

This conclusion is further supported by the research of drug addicts who use street drugs with dopamine agonist properties, such as cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine and other similar substances, as all illegal drugs dramatically increase the levels of dopamine in the brain. Indeed, drug addicts often have symptoms that resemble those present in psychosis, particularly after large doses or prolonged use. This type of addiction is usually referred to as "amphetamine psychosis" or "cocaine psychosis," which may produce experiences virtually indistinguishable from the positive symptoms associated with schizophrenia. In the early 1970s, several studies experimentally induced amphetamine psychosis in ordinary participants to better document the clinical pattern of schizophrenia.

It is also worth noting that when schizophrenics abuse street drugs (it should be noted that schizophrenia is comorbid with drug addiction), positive symptoms become much worse. For example, up to 75% of patients with schizophrenia have increased signs and symptoms of their psychosis when given moderate doses of amphetamine or other dopamine-like compounds/drugs, all given at doses that neurotypical volunteers do not experience any psychologically disturbing effects. Lastly, repeated exposure to high doses of antipsychotics (dopamine antagonists gradually reduced paranoid psychosis in these neurotypical participants. There are ethical issues with the above studies.

RESEARCH ANALYSIS ILLEGAL DRUGS

However, this type of research has also fallen out of favour with the scientific research community, as drug-induced psychosis is now thought to be qualitatively different from schizophrenia psychosis. Differences between the drug-induced states and the typical presentation of schizophrenia have now become more apparent, e.g., euphoria, alertness, and overconfidence. Some researchers believe these symptoms are more reminiscent of mania (manic side of bipolar depression) than schizophrenia.

POST-MORTEM STUDIES AND EARLY FINDINGS

Early studies often relied on post-mortem examinations to investigate dopamine receptors in the brains of individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia. Many of these studies reported increased dopamine receptor density, particularly in the striatum. However, this method is highly problematic for several reasons:

Real-Time Limitations: Post-mortem studies cannot measure dopamine activity in real time, a crucial requirement for understanding neurotransmitter function.

Medication Effects: Many individuals studied had taken antipsychotic drugs, which affect brain chemistry and receptor density. As a result, changes observed in post-mortem brains may reflect medication effects rather than the underlying biology of schizophrenia.

Generalisability Issues: Case studies from post-mortems often lack generalisability, as the brains studied may not represent the broader population of individuals with schizophrenia.

Diagnostic Ambiguity: Before the introduction of the DSM-5, schizophrenia samples often included individuals with bipolar disorder, catatonia, or a mix of negative and positive symptoms, which could skew findings.

These methodological issues explain why historical research findings on dopamine activity in schizophrenia were often inconsistent.

RESEARCH ON RATS

Chemical stimulation in rats is thought to support the dopamine hypothesis. In brief, rats are given dopamine antagonists (e.g., antipsychotic drugs such as chlorpromazine) and dopamine agonists (e.g., L-DOPA, PCP and amphetamines). The behaviour that rats show when given agonists is thought to be like the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia in humans. For example, several animal models of schizophrenia are based on the experimental observation that phencyclidine (PCP) and amphetamines can induce behavioural changes that include locomotor hyperactivity, stereotyped behaviour, and social withdrawal (Murray and Horita 1979).

RESEARCH ANALYSIS RATS

Rats are not comparable to humans; not only do they not have a language, which is one of the key problem areas in schizophrenia, but psychologists do not have a viable way of assessing how disorganised or hallucinogenic a rat’s thoughts are whilst on L-DOPA, as they can’t ask a rat if it is hallucinating or delusional. Moreover, as the clinical interview is the only valid way of assessing schizophrenia in humans, one wonders how the researchers got over that problem when determining the rats ‘supposedly’ positive schizophrenic symptoms; schizophrenia may be unique only to humans.

On the other hand, rats and humans share many similarities, including comparable hormonal and nervous systems. Plus, we have almost identical hind, mid-, and forebrains. More importantly, rats and humans share similar mesolimbic systems, the pathways through which dopamine is processed, so the research would be valuable for assessing how antagonists and agonists affect dopamine receptors.

COMMENTARY

ANALYSIS SPECIFIC TO THE ORIGINAL DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS.

Another major weakness of the original dopamine hypothesis is that it is not specific to schizophrenia at all. If schizophrenia were truly caused by excess dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway, this biochemical signature should be essentially unique to the disorder. It is not. The same pattern of striatal dopamine hyperactivity and increased D2/D3 receptor availability appears in psychotic bipolar mania, schizoaffective disorder, drug-induced psychosis (amphetamine, cocaine, L-DOPA), PTSD with psychotic features, and acute transient psychotic disorders. At the other end of the spectrum, low prefrontal dopamine is implicated in ADHD and some depressive states, yet antipsychotics are not used for those conditions. Every clinically effective antipsychotic works primarily by blocking dopamine D2 receptors and is routinely prescribed for acute mania and other non-schizophrenic psychotic states. Amphetamine psychosis, driven by massive dopamine release, can be virtually indistinguishable from paranoid schizophrenia while the drug is active, yet it clears completely once dopamine levels return to normal. In short, excess mesolimbic dopamine is strongly associated with psychosis in general, not with schizophrenia in particular. It represents a final common pathway for positive symptoms that many different illnesses, substances, and transient states can trigger. The original dopamine hypothesis, therefore, explains psychosis extremely well. Still, it cannot explain why one person develops the chronic, multifaceted illness we call schizophrenia while another experiences only a brief manic or drug-induced episode. Dopamine hyperactivity is real and essential, but it is only a partial and non-specific part of the story of schizophrenia itself.

TREATMENT-RESISTANT SCHIZOPHRENIA

A further issue is treatment resistance. Around one-third of people with schizophrenia show full D2-receptor occupancy on scans yet do not improve on dopamine-blocking medication. They meet the biochemical criteria of the original dopamine hypothesis, but reducing dopamine transmission does not reduce their positive symptoms. This challenges the claim that mesolimbic hyperdopaminergia is the fundamental cause of psychosis. Some clinicians argue this non-response may occur when antipsychotics are started long after symptom onset, but delayed treatment cannot account for all cases, indicating a distinct treatment-resistant subgroup.

NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS

More importantly, a large subset of schizophrenics do not suffer from positive symptoms and instead present with “negative” symptoms. In these cases, antipsychotics do not affect type-two negative symptoms whatsoever. Interestingly, if dopamine agonists, such as L-DOPA, are administered, these symptoms can improve. Thus, a significant problem with the original dopamine hypothesis is that dopamine is not implicated in type 2 schizophrenia, where negative symptoms predominate.

Over the years, researchers recognised that the original dopamine hypothesis, which explained positive symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, delusions) as a result of increased dopamine activity, failed to account for negative symptoms(e.g., apathy, flattened affect, and social withdrawal) and cognitive deficits (e.g., poor working memory, attention problems). But why did it take so long for researchers to recognise negative symptoms as a core feature of schizophrenia? And why did they initially assume blocking dopamine would improve all symptoms?

WHY WERE NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS INITIALLY IGNORED

For much of the 20th century, schizophrenia was primarily understood in terms of its positive symptoms, as these were the most obvious and disruptive. Early psychiatrists did recognise that some patients exhibited a form of progressive mental decline, including apathy and withdrawal. In 1899, Emil Kraepelin compared these symptoms to dementia, describing how specific individuals with schizophrenia seemed to deteriorate over time. In 1911, Eugen Bleuler introduced the term schizophrenia and identified features such as affective flattening, poverty of speech, and anhedonia as core symptoms of the disorder.

Despite these early observations, negative symptoms were largely ignored. They were not as dramatic as hallucinations and delusions, making them harder to study. Clinicians often assumed they were simply a reaction to psychosis rather than a distinct issue, believing that symptoms such as withdrawal and reduced speech were a byproduct of delusions or hallucinations. The focus of treatment was primarily on psychotic agitation, as this was considered the most pressing issue in hospitalised patients. As a result, positive symptoms took priority in both research and treatment. It was not until the 1970s and 1980s that negative symptoms were recognised as a distinct feature of schizophrenia, requiring separate investigation.

When antipsychotics were introduced in the 1950s, researchers initially believed they would improve all symptoms of schizophrenia, including negative ones. However, even as positive symptoms responded to treatment, many patients remained withdrawn and unmotivated, suggesting that negative symptoms were not merely a consequence of psychosis but an independent aspect of the disorder.

ALL ABOUT DOPAMINE

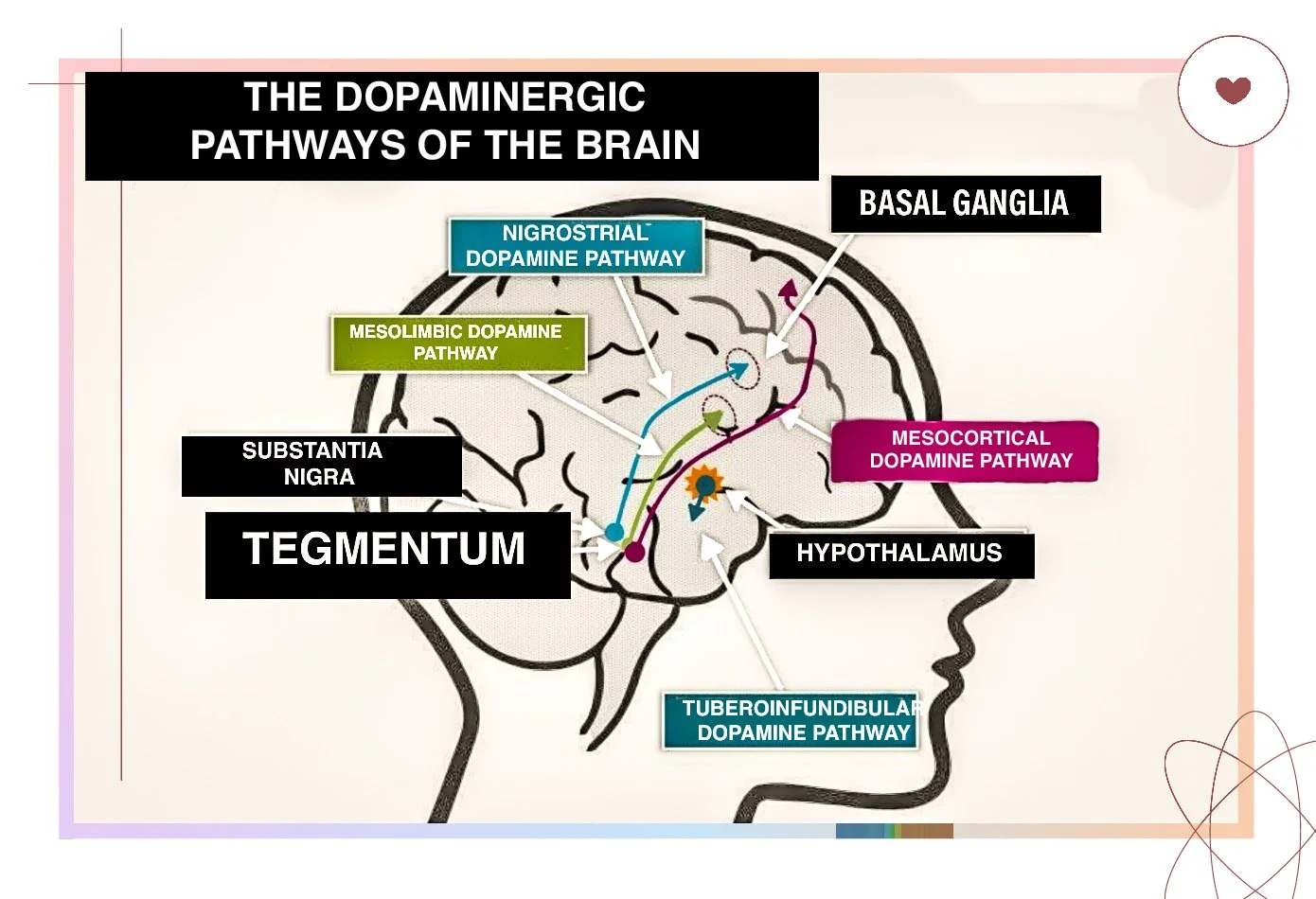

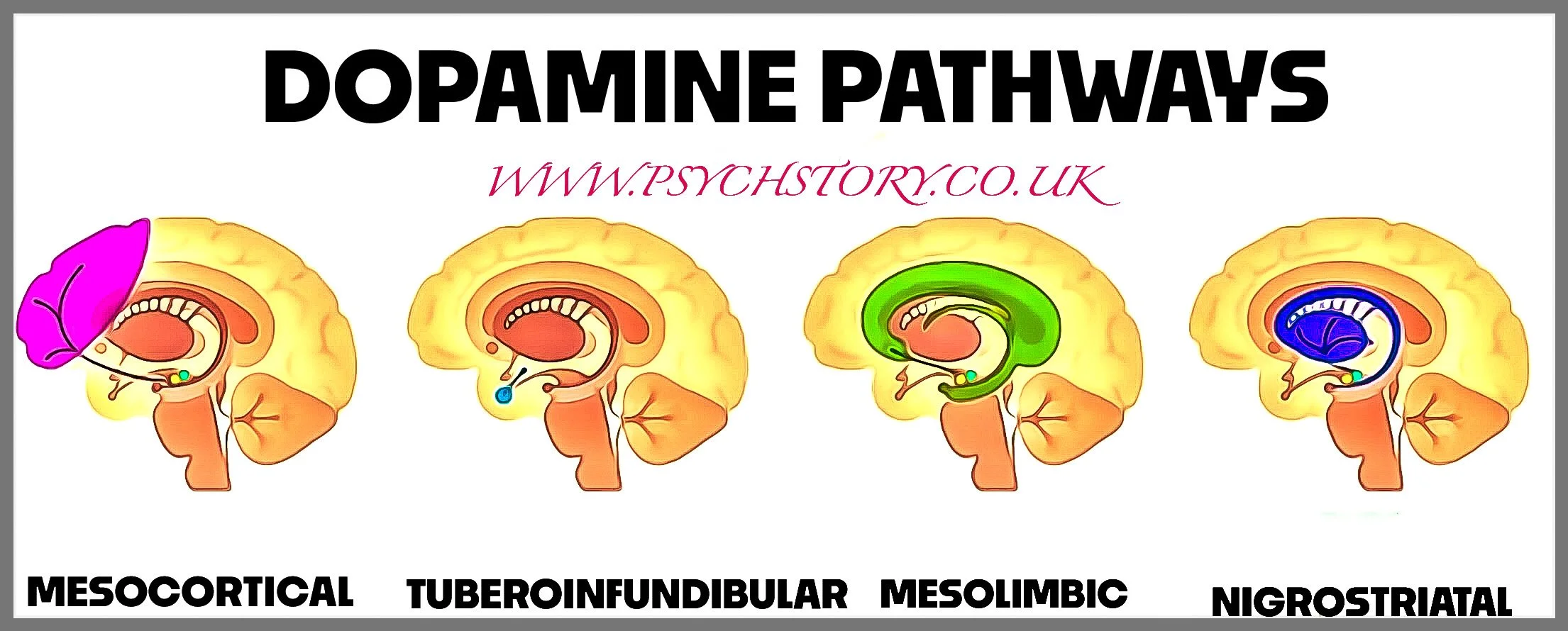

Schizophrenia is caused by too much dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway and too little in the mesocortical pathway; the other dopamine pathways (nigrostriatal and tuberoinfundibular) are only affected by treatment, not by the disorder itself.

THE DOPAMINE PATHWAYS IN DETAIL

NIGROSTRIATAL PATHWAY (D1 + D2) – VOLUNTARY MOVEMENT (NOT IMPLICATED IN SZ)

Dopamine’s earliest role is the control of voluntary movement. In evolutionary terms, this function arose because, unlike plants, animals need to move to survive. Trees absorb nutrients through the soil, but animals must move to obtain food and escape danger. Dopamine evolved as the chemical signal that enables voluntary movement—deciding when a movement should begin, how forceful it should be, and whether it should continue. In the brain, this system runs through the basal ganglia, a group of structures deep beneath the cortex that regulate movement initiation and control. A key component of this circuit, the striatum, receives dopamine signals that effectively “unlock” a movement so it can be carried out. When dopamine in this pathway decreases, movements become slow and rigid; when the dopamine system fails, voluntary movement becomes impossible. Parkinson’s disease illustrates this clearly because it involves the degeneration of the dopamine-producing neurons that supply this pathway, resulting in the progressive inability to initiate voluntary movement.

MESOLIMBIC DOPAMINE PATHWAY (D2) – REWARD AND SALIENCE ( IMPLICATED IN SZ)

From this foundation, dopamine became integrated into broader behavioural systems. Once an organism’s actions can lead to success or failure, it is adaptive for those outcomes to influence future behaviour. Natural selection, therefore, linked learning, motivation, and goal-directed behaviour to the same dopaminergic system that controls voluntary action. Because all deliberate behaviours involve dopamine, actions that lead to good outcomes naturally become stronger: the organism experiences an increased dopamine response, reinforcing the behaviour. Dopamine, therefore, came to regulate motivation by marking specific actions or stimuli as significant and generating the drive to pursue them. This system is known as the mesolimbic pathway, in which dopamine acts heavily on D2 receptors in areas such as the nucleus accumbens and the amygdala. Under normal conditions, this pathway flags important or rewarding events so the organism learns what is worth repeating. It is part of the same reward and salience system that later becomes relevant in psychosis when dopamine levels become excessive. These principles are evident in real behaviour. A pigeon that pecks a button and unexpectedly receives grain will continue pecking because dopamine spikes have taught it that “this action works.” A rat that presses a lever and receives nothing will quickly stop because a drop in dopamine signals that the action is ineffective. The exact process appears in humans: a student who revises and then sees an improved grade is more likely to revise again; someone who feels better after exercise is more likely to return to the gym; someone who posts on social media and receives a burst of likes is more likely to post again. These are dopamine-driven learning loops. The brain uses rises and falls in dopamine to link an action with its consequence and to judge whether the outcome was better or worse than expected. Over time, this system expands into salience detection, goal-directed behaviour, and the regulation of approach and persistence. Dopamine’s reinforcement system can also malfunction.

MESOLIMBIC PATHWAY (D2) AND ADDICTION

Addictive substances produce dopamine spikes far larger than anything found in natural rewards, artificially teaching the brain that the drug is the highest-priority behaviour available. This distorts learning and motivation. Similar distortions occur in compulsive behaviours such as gambling or binge-eating, where unpredictable rewards or emotional relief generate exaggerated dopamine responses that reinforce the behaviour even when it is harmful.

MESOLIMBIC PATHWAY THE VENTRAL STRIATUM (D2) AND PSYCHOSIS

The same mesolimbic pathway that supports reinforcement typically becomes pathological when dopamine signalling—primarily through D2 receptors—is too strong. Excess D2 activation in the Mesolimbic system does four things relevant to schizophrenia: it inflates the motivational relevance of neutral stimuli, it amplifies emotional responses to trivial events, it destabilises discrimination between internal/external signals, and it reinforces delusional conclusions once formed. Together, these distortions generate the positive symptoms — hallucinations, delusions, and ideas of reference.

*Note on the Associative Striatum: Contemporary neuroimaging (e.g., Howes et al., 2012) shows elevated dopamine synthesis in the associative striatum, a region involved in cognitive processing. This finding is relevant to advanced models of schizophrenia but does not replace the core mesolimbic–mesocortical explanation. It is considered an extension detail, not essential A-level content.

THE MESOCORTICAL DOPAMINE SYSTEM

WHY DOES TOO LITTLE DOPAMINE IN THE MESOCORTICAL SYSTEM CAUSE NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS?

In contrast, the mesocortical pathway, which connects the VTA to the prefrontal cortex, is underactive in schizophrenia. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-order thinking, planning, motivation, and emotional regulation.

Dopamine in the prefrontal cortex primarily binds to D1 receptors, which are excitatory—meaning they increase neuronal activity and help maintain cognitive and motivational processes. When dopamine levels in this region are too low, D1 receptors receive insufficient stimulation, reducing neural activity and leading to:

Avolition (lack of motivation): Individuals struggle to initiate and sustain essential self-care activities.

Affective flattening: Emotional expression becomes diminished, leading to reduced facial expressions, a monotone voice, and social withdrawal.

Cognitive impairments: Attention, planning, and decision-making deficits make complex tasks challenging.

SUMMARY: THE FOUR DOPAMINE PATHWAYS

NIGROSTRIATAL PATHWAY

Route: Substantia nigra → Dorsal striatum

Function: Motor control, voluntary movement

In schizophrenia:

Not diseased in the illness itself.

BUT affected by medication.

D2 blockade →

Parkinsonism

akathisia

tremor

tardive dyskinesia

This is the iatrogenic pathway: side effects, not symptoms.

MESOLIMBIC PATHWAY

Route: VTA → Nucleus accumbens (ventral striatum), amygdala

Function: Reward, salience, motivation, emotion

In schizophrenia:

Hyperdopaminergic (too much dopamine)

→ Positive symptoms:

hallucinations

delusions

ideas of reference

thought disorder (via striatal D2 overstimulation)

This is the core “excess dopamine” pathway.

MESOCORTICAL PATHWAY

Route: VTA → Prefrontal cortex (especially dorsolateral PFC)

Function: Executive function, working memory, motivation, planning

In schizophrenia:

Hypodopaminergic (too little dopamine)

→ Negative and cognitive symptoms:

avolition

flat affect

poor attention

impaired planning

working memory deficits

This is the part that the original dopamine hypothesis missed; it is central in the reformulated version.

TUBEROINFUNDIBULAR PATHWAY

Route: Hypothalamus → Pituitary gland

Function: Hormone regulation (prolactin control)

In schizophrenia:

Not part of the disorder,

BUT affected by antipsychotics.

D2 blockade →

raised prolactin

sexual dysfunction

menstrual disruption

galactorrhoea

SUMMARY: WHICH PATHWAYS ARE IMPLEMENTED IN SCHIZOPHRENIA?

DOPAMINE PATHWAYS DIRECTLY AFFECTED BY SCHIZOPHRENIA

Mesolimbic (↑ dopamine) → positive symptoms

Mesocortical (↓ dopamine) → negative and cognitive symptoms

DOPAMINE PATHWAYS AFFECTED BY ANTI PSYCHOTIC

Nigrostriatal → motor side effects

Tuberoinfundibular → prolactin side effects

DOPAMINE RECEPTORS (WHY THERE ARE FIVE)

Students usually learn “dopamine” as if it were one

In reality, dopamine has several different “docking sites” in the brain, called receptors.

These receptors are slightly different shapes, so dopamine produces different effects depending on which one it binds to.

There are five dopamine receptors — D1, D2, D3, D4, D5. They are named in the order they were discovered:

They are not five different kind of dopamine. they are five ways different parts of the brain can read the same dopamine signal.

DOPAMINE RECEPTORS ARE DIVIDED INTO TWO PROMINENT FAMILIES

Scientists then group them based on how they behave:

D1-LIKE RECEPTORS (D1, D5): Generally stimulate neuron activity (excitatory effects).

D2-LIKE RECEPTORS (D2, D3, D4): Generally inhibit neuron activity (inhibitory effects).

These effects vary depending on brain region and neural pathway.

THE ONLY TWO RECEPTORS RELEVANT TO SCHIZOPHRENIA

For schizophrenia, only two of these receptors matter: D1 and d2

MESOLIMBIC PATHWAY

(↑ D2 → positive symptoms (lack of salience → hallucination and delusions ).MESOCORTICAL PATHWAY

(↓ D1 → negative symptoms (cognitive deficits → poverty of speech, thought and lack of motivation).

Students are actually confused because hallucinations are caused by too much D2 activity even though D2 is described as inhibitory, and the opposite seems true for D1. The key is that “inhibitory” and “excitatory” describe what happens inside a single neuron, not what happens to the whole pathway.

D2 is inhibitory at the cell level, but when there is too much dopamine stimulating D2 receptors in the mesolimbic pathway, the entire circuit becomes overactive, not calmer. This overactivity disrupts salience (the ability to know what is important), which produces hallucinations and delusions.

D1 is excitatory at the cell level, but when there is too little dopamine acting on D1 receptors in the mesocortical pathway, the circuit becomes underactive. This underactivity leads to cognitive problems and negative symptoms such as poverty of speech, reduced thought, and lack of motivation.

So:

D2 RECEPTORS – POSITIVE SYMPTOMS

• Highly concentrated in the mesolimbic pathway

• Overstimulation → hallucinations, delusions, ideas of reference

• All antipsychotics work by blocking D2

D2 = inhibitory, but overstimulation in the mesolimbic pathway → positive symptoms

D1 RECEPTORS – NEGATIVE AND COGNITIVE SYMPTOMS

• Found in the prefrontal cortex

• Understimulation → apathy, poor planning, flat affect, impaired working memory

D1 = excitatory, but understimulation in the mesocortical pathway → negative symptoms

THE OTHER THREE D RECEPTORS AND WHY THEY AREN’T IMPORTANT IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

D3 – reward/motivation, addiction

D4 – novelty seeking, attention

D5 – learning/memory, weakly expressed

They exist, but they do not drive schizophrenia’s core symptoms, so they remain peripheral in modern models.

SUMMARY

“Dopamine has five receptors, but schizophrenia is almost entirely about D2 being too active and D1 being too inactive.”

THE REFORMULATED DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS

Dopamine remains central in schizophrenia, but the reformulated hypothesis specifies where it is abnormal and in which direction, instead of treating the disorder as a general excess. It identifies three pathways. In the mesolimbic pathway, dopamine is too high, overstimulating D2 receptors, which makes neutral events feel important and drives hallucinations, delusions, and ideas of reference. In the mesocortical pathway, dopamine is too low, particularly at D1 receptors in the prefrontal cortex, producing the negative and cognitive symptoms the original hypothesis ignored: apathy, flat affect, impaired planning, and difficulties with attention and working memory. The nigrostriatal pathway, responsible for movement, is usually intact in the illness but becomes affected when antipsychotics block D2 receptors there, causing Parkinsonian side-effects and tardive dyskinesia; these belong to treatment, not to schizophrenia itself.

The advantage of the reformulated model is that it fits the full clinical range. It explains why some individuals present with florid psychosis while others show mainly motivational, emotional, or cognitive deterioration, and why a significant minority do not respond to standard D2-blocking medication. Rather than forcing all cases into a single “excess dopamine” story, it recognises a pattern of hyperactivity in one dopaminergic system and underactivity in another, which accommodates the people the original hypothesis left out.

IN SUMMARY

DOPAMINE RECEPTORS SHAPE HOW WE RESPOND TO REWARDING EXPERIENCES. Imagine you get a message from someone you like. Your phone lights up — dopamine surges. Whether that moment feels good, feels worth doing anything about, or feels bizarrely overloaded with meaning depends on just two receptor families working in two different brain regions.

D2 RECEPTORS – THE “THIS FEELS GOOD” RECEPTOR Mainly in the mesolimbic pathway (nucleus accumbens / ventral striatum)

Normal D2 activity → the message actually feels pleasurable and rewarding.

Too much D2 stimulation (mesolimbic hyperactivity) → ordinary things start feeling unnaturally important or personally significant → aberrant salience → delusions, hallucinations, ideas of reference. This is the core mechanism of positive symptoms in schizophrenia.

Blocking D2 receptors (all antipsychotics do this) → reduces positive symptoms, but as a side-effect can also make everything feel flat and unrewarding (secondary anhedonia).

D1 RECEPTORS – THE “THIS IS WORTH DOING SOMETHING ABOUT” RECEPTOR, mainly in the prefrontal cortex.

Normal D1 activity → you feel motivated to reply, can plan what to say, and the reward still feels worth the effort.

Too little D1 stimulation in the prefrontal cortex (prefrontal hypodopaminergia) → even when something is objectively rewarding, it doesn’t feel worth the effort. Motivation collapses, thinking feels sluggish, emotions go flat. This is the primary mechanism of negative and cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia (avolition, anhedonia-as-inability-to-pursue-reward, blunted affect, poor executive function).

DIFFERENT TRAJECTORIES OF POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS

One key distinction between positive and negative symptoms is their progression over time. The difference in how these symptoms emerge, and progress is due to how dopamine dysfunction unfolds in different brain pathways.

WHY POSITIVE SYMPTOMS ARE ACUTE AND EPISODIC

Positive symptoms suddenly fluctuate because they are linked to dopamine surges in the mesolimbic system. Dopamine release in this region is influenced by external and internal triggers, such as stress, drug use, and even normal brain activity fluctuations. These factors can cause dopamine spikes, leading to episodes of psychosis that seem to appear rapidly.

This explains why hallucinations and delusions can be episodic—they often emerge during acute psychotic episodes, sometimes triggered by environmental factors or stress. Positive symptoms usually show rapid improvement with treatment because the mesolimbic pathway can be temporarily stabilised with dopamine-blocking medication.

WHY NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS DEVELOP SLOWLY AND ARE CHRONIC

In contrast, negative symptoms progress slowly and persist over time because they are associated with a gradual decline in dopamine function in the mesocortical pathway. Unlike the mesolimbic system, which reacts dynamically to changes in dopamine, the mesocortical system declines progressively, much like neurodegenerative diseases affect brain function over time.

This gradual decline in dopamine transmission to the prefrontal cortex means that motivational and cognitive impairments worsen over time rather than appearing suddenly. Since dopamine surges or episodic spikes do not drive this process, negative symptoms tend to be persistent and resistant to change, making them more long-lasting and difficult to treat compared to positive symptoms.

SUMMARY

The original dopamine hypothesis only explained positive symptoms, assuming all schizophrenia symptoms resulted from too much dopamine.

Negative symptoms were initially ignored or assumed to be a reaction to psychosis, not a separate dysfunction.

Early researchers did not yet understand that dopamine affects different brain regions differently, leading to false assumptions about treatment.

By the 1970s, it became clear that positive symptoms were caused by too much dopamine, while negative symptoms were linked to too little dopamine.

The reformulated dopamine hypothesis recognised that schizophrenia involves both hyperdopaminergic and hypodopaminergic activity, leading to a broader understanding of the disorder.

This updated model paved the way for research into cognition, motivation, and other neurotransmitters, moving beyond dopamine alone as the cause of schizophrenia.

RESEARCH ANALYSIS OF THE REFORMULATED DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS

ADVANCES IN BRAIN IMAGING AND NEURAL CORRELATES

Modern techniques, such as PET (positron emission tomography) and fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), have revolutionised the study of dopamine activity in living brains. These imaging methods provide real-time evidence of neurotransmitter function and structural changes in the brains of individuals with schizophrenia.

BRAIN IMAGING EVIDENCE FOR POSITIVE SYMPTOMS

Positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, have been linked to hyperdopaminergic activity in subcortical regions, particularly the mesolimbic system. Key findings include:

Increased Dopamine Receptors: Studies consistently show excess dopamine D2 receptors in the striatum, caudate nucleus, and amygdala.

Faster Dopamine Metabolism: Individuals with schizophrenia often exhibit increased dopamine turnover, reflecting faster synthesis and breakdown of dopamine in the brain.

Enhanced Dopamine Release: After taking amphetamines, which increase dopamine availability, individuals with schizophrenia release significantly more dopamine (particularly in the striatum) compared to neurotypical controls. This supports the link between dopamine overactivity and psychotic symptoms.

Auditory Hallucinations: Reduced activity in the superior temporal and anterior cingulate gyrus has been directly associated with auditory hallucinations. Patients with these symptoms exhibit lower activation in these brain areas than healthy individuals.

RESEARCH STUDIES

Lindström et al. (1999) used PET scans to measure dopamine synthesis in people with schizophrenia and found increased dopamine production in the striatum compared to controls. This supports the idea that hyperdopaminergic activity in the striatum contributes to positive symptoms like hallucinations and delusions.

Howes et al. (2012) also used PET imaging. They found that people at high risk of developing schizophrenia had elevated dopamine synthesis in the striatum, suggesting that dopamine overactivity occurs before the onset of symptoms, supporting its role in causing psychosis rather than being a result of the disorder.

Amphetamine challenge studies (e.g., Laruelle et al., 1996) found that individuals with schizophrenia released more dopamine in response to amphetamines than control participants. Since amphetamines increase dopamine levels, this suggests that people with schizophrenia already have excess dopamine activity in the striatum, reinforcing the link between hyperdopaminergic and positive symptoms.

These findings suggest that hyperactivity in dopamine pathways and reduced activity in specific cortical areas act as neural correlates of positive symptoms.

BRAIN IMAGING EVIDENCE FOR NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS

Negative symptoms, such as avolition (loss of motivation) and social withdrawal, have been linked to hypodopaminergic activity in cortical regions. Key findings include:

Reduced Activity in the Ventral Striatum: The ventral striatum plays a key role in anticipating rewards and driving motivation. Abnormalities in this area are strongly linked to avolition.

Prefrontal Cortex and D1 Receptors: Underfunctioning of D1 receptors in the prefrontal cortex correlates with cognitive and motivational impairments observed in schizophrenia. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-order functions, including planning, problem-solving, and emotional regulation.

Neuroimaging Evidence: Patients with negative symptoms exhibit significantly lower prefrontal cortex activation during executive function tasks, further supporting the role of dopamine hypoactivity in these symptoms.

These findings underscore the significance of dopamine hypoactivity in cortical areas as a neural correlate of negative symptoms.

RESEARCH STUDIES

Davis et al. (1991) proposed the reformulated dopamine hypothesis, arguing that while positive symptoms are linked to excess dopamine in the striatum, negative symptoms are caused by dopamine underactivity in the prefrontal cortex.

Juckel et al. (2006) found that individuals with schizophrenia showed reduced dopamine activity in the prefrontal cortex, which was correlated with negative symptoms such as avolition and emotional flattening.

Weinberger et al. (1986) found that patients with prefrontal cortex damage displayed negative cognitive symptoms similar to those seen in schizophrenia. This suggests that dopamine underactivity in the prefrontal cortex plays a key role in these symptom clusters.

Goldman-Rakic et al. (2004) found that lower D1 receptor density in the prefrontal cortex was associated with cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, supporting the idea that hypodopaminergic in the prefrontal cortex contributes to working memory and decision-making impairments.

Patel et al. (2010) found that dopamine dysfunction in both the striatum and prefrontal cortex was present in patients with schizophrenia, confirming the dual role of hyperdopaminergic and hypodopaminergic activity in different pathways.

Takahashi et al. (2006) used MRI and PET scans to show that prefrontal cortex dysfunction was linked to reduced dopamine receptor availability and impaired cognitive function, further supporting the role of hypodopaminergic activity in negative symptoms.

OTHER EVIDENCE:

The new class of antipsychotics known as Atypicals, which were developed in the 1990s, support the reformulated dopamine hypothesis as they show that blocking serotonin in addition to dopamine does alleviate negative symptoms.

Atypical antipsychotics receptors, specifically block:

Dopamine D2 receptors

Serotonin 5-HT₂A receptors

This dual action is a key feature of atypical (second-generation) antipsychotics, which distinguish themselves from typical antipsychotics by:

Reducing positive symptoms (via D2 antagonism in the mesolimbic pathway)

Improving negative/cognitive symptoms and reducing side effects (via 5-HT₂A antagonism, especially in the prefrontal cortex)

At first glance, it seems illogical that blocking serotonin receptors could help with symptoms of schizophrenia that are thought to be caused by too little dopamine. If adverse symptoms are linked to hyperdopaminergic activity in the mesocortical pathway, and drugs like risperidone and clozapine are dopamine antagonists, how do they avoid worsening this deficiency?

The answer lies in the dual mechanism of certain atypical antipsychotics. These drugs block D2 dopamine receptors — particularly in the mesolimbic pathway — to reduce positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. However, they also block 5-HT₂A serotonin receptors, especially in the prefrontal cortex. This is not because serotonin itself causes schizophrenia symptoms, but because 5-HT₂A activation inhibits the typical dopamine release. By blocking serotonin receptors, atypical antipsychotics remove that inhibition, enhancing dopamine release in mesocortical areas where it is abnormally low.

So it's not that serotonin is causing negative symptoms — it's that blocking serotonin allows dopamine to be restored in underactive regions. This selective enhancement is the reason second-generation antipsychotics are often better at treating negative and cognitive symptoms compared to earlier drugs, which suppress dopamine across the board.

THE REFORMULATED DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS: WHAT IT DID NOT ADDRESS

The reformulated dopamine hypothesis was a significant improvement over the original theory. However, despite its advancements, this hypothesis still left key questions unanswered.

OTHER NEURAL CORRELATES BEYOND DOPAMINE

The dopamine hypothesis remains central to understanding positive symptoms, but schizophrenia is biologically heterogeneous. Neuroimaging and post-mortem studies have identified several additional neural correlates that help explain the full spectrum of the illness, particularly negative and cognitive symptoms.

ENLARGED CEREBRAL VENTRICLES AND SYMPTOM SUBTYPES

One of the most replicated structural findings is ventricular enlargement — an increase in the size of the fluid-filled spaces within the brain, reflecting a loss of surrounding brain tissue. Meta-analyses show that, on average, individuals with schizophrenia have lateral ventricles 20–40 % larger than healthy controls. This enlargement is clinically meaningful:

Patients with markedly enlarged ventricles tend to show more prominent negative symptoms (poverty of speech, flat affect, avolition, anhedonia) and cognitive deficits.

Those with relatively normal ventricle size are more likely to present with positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, disorganised behaviour).

Classic studies (e.g., the “Crow subtypes”) initially led to the proposal of Type I (dopamine-driven, positive symptoms, standard structure) versus Type II (structural brain changes, negative symptoms, poorer outcome) schizophrenia. Although the dichotomy is now seen as oversimplified, ventricular size remains one of the strongest predictors of long-term functional impairment. Important caveat: prolonged exposure to first-generation antipsychotics can contribute to ventricular enlargement over time, so some of the observed differences may be partly iatrogenic rather than purely neurodevelopmental.

PREFRONTAL CORTEX HYPOFUNCTION

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is consistently underactive in schizophrenia, both at rest and during tasks requiring working memory, executive function, or planning. This hypoprefrontal pattern correlates with:

Disorganised thinking and speech

Impaired attention and concentration

Negative symptoms, especially avolition and reduced goal-directed behaviour

Hypofrontality is thought to arise from a combination of reduced grey-matter volume, disrupted white-matter connectivity, and impaired GABAergic inhibition of pyramidal neurons, deficits that are only partially reversed by current medications.

ADDITIONAL KEY FINDINGS

Reduced hippocampal volume → memory and contextual processing deficits

Thalamic abnormalities → disrupted sensory gating and information filtering

Glutamate dysregulation (NMDA receptor hypofunction) → a leading alternative/complementary hypothesis to dopamine excess, particularly for cognitive and negative symptoms

Widespread reductions in cortical thickness and synaptic density, suggesting a disorder of connectivity rather than a single localised lesion

In summary, while dopamine dysregulation elegantly explains the emergence of aberrant salience and positive symptoms, structural changes (especially ventricular enlargement) and prefrontal hypofunction better account for the chronic cognitive impairments and negative symptoms that often determine long-term disability. Modern models, therefore, view schizophrenia as a disorder of distributed network dysfunction, with dopamine excess as one crucial, but not exclusive, component.

NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS ARE STILL NOT FULLY ADDRESSED

NEGATIVE SYMPTOMS AND COGNITIVE DEFICITS

The reformulated dopamine hypothesis was explicitly developed to address the original theory’s inability to explain negative symptoms and cognitive deficits. By adding prefrontal hypodopaminergia to the established mesolimbic hyperdopaminergia, it aimed to provide a unified dopamine-based account of the full symptom spectrum. It has not succeeded in doing so. Although reduced prefrontal dopamine does contribute to aspects of cognitive impairment and diminished motivation, two significant difficulties remain unresolved:

Negative symptoms show enormous inter-individual variation that is not predicted by the degree of presumed prefrontal dopamine deficit.

Cognitive deficits (working memory, executive function, processing speed) typically persist at premorbid levels even when positive symptoms are fully remitted, and striatal dopamine function has been normalised by antipsychotic treatment.

These persistent gaps demonstrate that, despite the intentions of the reformulated hypothesis, dopamine dysregulation alone cannot adequately account for negative symptoms and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia.

DELAYED THERAPEUTIC RESPONSE

Another significant challenge for a purely dopaminergic explanation is the puzzling time course of antipsychotic treatment.All classical and most atypical antipsychotics block D2 receptors almost immediately — within hours of the first dose, striatal dopamine transmission is sharply reduced. If the positive symptoms of schizophrenia were nothing more than the direct, real-time consequence of excess dopamine signalling, clinical improvement should also appear within hours or days.It does not.Instead, hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder typically take 2–6 weeks to subside significantly, even though receptor occupancy has been near-maximal from the very beginning. This delayed therapeutic response shows that simply turning off the dopamine tap is not enough. Downstream adaptive changes in neuronal circuits — alterations in gene expression, receptor sensitisation or desensitisation, and interactions with other neurotransmitter systems (glutamate, GABA, serotonin) — are required before symptoms actually improve. The lag is robust evidence that dopamine hyperactivity is a crucial trigger, but the persistence of psychosis depends on secondary neuroplastic changes that take weeks to reverse. In other words, dopamine excess may start the fire, but the fire keeps burning through mechanisms that are no longer directly dependent on ongoing dopamine release. This delayed onset is one of the most evident signs that schizophrenia cannot be reduced to a simple, immediate dopamine imbalance.

BEYOND DOPAMINE: MULTIPLE NEUROTRANSMITTERS AND THE ROLE OF GLUTAMATE

The dopamine hypothesis tells us where things go wrong in the brain, but it never answers the most critical question: why does the dopamine system go wrong in the first place? Arvid Carlsson (the scientist who discovered dopamine’s role as a neurotransmitter and won the Nobel Prize for it) believed dopamine was only part of the picture. He kept asking: What is actually causing the dopamine levels to become too high in some areas and too low in others? His answer: glutamate. Glutamate is the brain’s primary “on” switch — the most common excitatory messenger. It usually keeps dopamine under tight control. Special docking stations called NMDA receptors are critical: they act like brakes and accelerators for dopamine neurons. When those NMDA receptors don’t function properly (a condition called NMDA receptor hypofunction), the control system breaks down. The result is precisely what we see in schizophrenia:

Too much dopamine floods the pathways that produce hallucinations and delusions (positive symptoms).

Too little dopamine reaches the front of the brain, leading to poor concentration, lack of motivation, and flat emotions (cognitive deficits and negative symptoms).

This simple idea explains several things that the pure dopamine theory can’t:

Why symptoms take weeks to improve even though medicines block dopamine receptors within hours — you’re treating the flood, not fixing the broken pipe.

Why ordinary antipsychotics help voices and paranoia but do almost nothing for motivation, emotions, or thinking problems — they only target dopamine, not the glutamate fault that’s driving the dopamine chaos.

Why clozapine (still the most effective drug for tough cases) works so much better — on top of gentle dopamine blocking, it helps repair glutamate/NMDA signalling in several ways.

In everyday language:

Dopamine is the smoke.

Glutamate/NMDA problems are the fire. Many researchers now believe the real starting problem in schizophrenia is faulty glutamate signalling, and the dopamine imbalance is just what happens afterwards. That’s why the future of better treatments lies in fixing glutamate, not just keeping mopping up excess dopamine

WHY DOES CLOZAPINE WORK WHEN OTHER DRUGS DON’T?

Traditional antipsychotics block D2 receptors, which help with positive symptoms but do not treat negative symptoms. Clozapine, a drug that works on both dopamine and glutamate, is effective in people who don’t respond to D2 blockers. This suggests that glutamate, not just dopamine, plays a role in schizophrenia.

EVALUATION OF ALL DOPAMINE HYPOTHESES

At this stage, dopamine dysregulation is recognised as a real and essential feature of schizophrenia, but it is no longer considered the primary or initiating abnormality. The glutamate/NMDA receptor hypofunction hypothesis, neurodevelopmental models, and evidence of immune/inflammatory disturbance have all placed dopamine dysregulation downstream in the causal pathway. One fundamental question, however, remains unresolved: Which comes first — the more profound biological disturbance (NMDA receptor hypofunction, faulty synaptic pruning, prenatal insults, early immune activation, genetic risk affecting brain maturation, etc.) or the disorder itself?

In other words, do these early brain changes cause schizophrenia, or could the process of the illness (or its prodromal and chronic phases) feed back and progressively worsen the original biological faults? The majority of researchers now regard the early abnormalities as primary and causal: schizophrenia emerges because critical developmental processes went wrong long before the first psychotic episode. Nevertheless, bidirectional effects cannot be entirely excluded. Chronic psychosis, excitotoxicity, or ongoing inflammation might amplify the initial damage and create a vicious cycle. Thus, although the weight of evidence strongly favours a primary neurodevelopmental origin, the direction of causality is not yet 100 % settled; a residual chicken-and-egg element persists.

ALTERNATIVE BIOLOGICAL EXPLANATIONS

Although the dopamine hypothesis remains influential and continues to guide much of the pharmacological treatment of positive symptoms, most researchers now regard it as overly reductionist. Schizophrenia is increasingly understood as a disorder of much broader neurobiological dysfunction that begins long before the first psychotic episode. Two major complementary frameworks have gained prominence:

Immune and glial dysfunction

Glial cells (astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes), which far outnumber neurons, are frequently abnormal in schizophrenia. Post-mortem studies, PET imaging, and genetic findings show evidence of chronic low-grade neuroinflammation and immune dysregulation. This persistent inflammatory state can damage synapses, impair glutamate clearance, and disrupt dopamine regulation — suggesting that immune activation may be an essential contributor to the illness rather than a simple by-product.Neurodevelopmental models

Schizophrenia is now widely regarded as a disorder of early brain development. Risk factors acting prenatally (maternal infection, malnutrition, stress) or perinatally (birth complications), combined with genetic vulnerability, interfere with neuronal migration, differentiation, and later adolescent synaptic pruning. The result is excessive synapse elimination in some regions and insufficient pruning in others, leading to dysfunctional brain circuits and imbalanced excitatory–inhibitory signalling that only become clinically apparent when the maturing brain is placed under adult-level demands.

These perspectives do not invalidate the dopamine findings; they place dopamine dysregulation within a much longer causal chain. Glutamate/NMDA receptor hypofunction is currently the leading candidate for the core upstream deficit that links many of these early insults, with dopamine hyperactivity, GABAergic interneuron loss, and neuroinflammation emerging as downstream consequences. Together, these lines of evidence portray schizophrenia as a complex, multi-factorial neurodevelopmental disorder rather than a condition that can be fully explained by abnormality in any single neurotransmitter system.

ISSUES AND DEBATES FOR BIOLOGICAL THEORIES - GENETIC AND NEURAL CORRELATES

DETERMINISM

Biological explanations of schizophrenia are inherently deterministic: they propose that genetic risk, early brain insults, and neurochemical imbalances heavily — or even entirely — dictate whether someone develops the disorder. This has both positive and negative implications.ADVANTAGES

Removes blame from parents (no more “refrigerator mother” theories) and from patients themselves.

Strongly reduces stigma: schizophrenia is framed as a brain disease, not a moral failing or weakness of character.

Encourages society to provide medical care and support rather than punishment or exclusion.

DISADVANTAGES

Can lead to fatalism: patients and families may feel “it’s in the genes/brain, so nothing we do matters,” discouraging psychological therapies, lifestyle changes, or personal effort.

May foster hopelessness and depression (“I was doomed from the start”).

Genetic determinism can indirectly increase stigma in other ways — for example, some people may be reluctant to form relationships or have children with someone who has schizophrenia because of perceived hereditary risk.

In short, the deterministic nature of biological models has been hugely valuable in reducing guilt and outdated blame, but it carries the risk of therapeutic nihilism if taken to mean that biology is the only thing that matters.

THERAPEUTIC NIHILISM

Therapeutic nihilism is the belief that, because schizophrenia is a biological brain disease with strong genetic and neurodevelopmental roots, non-biological interventions are essentially pointless. Patients, families, or even clinicians may conclude:

“Why bother with therapy, exercise, social skills training, or family work if the problem is faulty genes and NMDA receptors?”

“Medication is the only thing that can help; everything else is just window dressing.”

This attitude can become self-fulfilling. When people stop trying psychological or social approaches, recovery rates fall, hospital readmissions rise, and the illness often appears more chronic and disabling than it needs to be. In reality, even with a transparent biological substrate, outcomes improve dramatically with early intervention, cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp), family intervention, supported employment, and lifestyle changes. Therapeutic nihilism ignores these evidence-based treatments and risks turning a partially manageable condition into a life sentence.

PHYSIOLOGICAL REDUCTIONISM & NATURE VS. NURTURE

Biological explanations of schizophrenia are physiologically reductionist. They attempt to account for a highly complex and varied disorder entirely in terms of genes, neurotransmitters (most famously dopamine), brain structure, and other measurable physiological processes. The underlying logic is straightforward: humans are biological organisms, so even the most intricate mental experiences and behaviours should, in principle, be reducible to neurochemical and genetic mechanisms.This reductionist stance has undeniable strengths, but it also attracts criticism for overlooking the person as a whole and for failing to acknowledge the constant interaction among biology, psychology, and the social environment. Identical twins share 100 % of their genes, yet concordance for schizophrenia is only around 48 %. Environmental factors such as highly expressed emotion in families, childhood trauma, heavy cannabis use, migration, and urban upbringing dramatically increase the risk of onset or relapse. No single physiological abnormality is ever sufficient on its own. The old nature-versus-nurture debate is therefore regarded as outdated. Biology is indispensable, yet claiming it is the sole cause ignores overwhelming evidence of psychological and social contributions.

THE DIATHESIS-STRESS / BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL

The DSM-5’s decision to rename the condition “schizophrenia spectrum disorder” formally acknowledges that there is no single cause; instead, many different combinations of factors can produce the same broad clinical picture. This recognition has replaced the old nature-nurture argument with a widely accepted integrative framework known as the diathesis-stress model (often called the biopsychosocial model in clinical settings; the two terms refer to essentially the same idea).The diathesis-stress model proposes that schizophrenia develops when a biological vulnerability (the diathesis) — such things as polygenic risk, C4 gene variants that affect synaptic pruning, prenatal infections, birth complications, or glutamate and dopamine dysregulation — is combined with sufficient environmental stress, such as abuse, family conflict, cannabis use, migration, urban living, or significant life events. Neither biological vulnerability nor environmental stress is sufficient on its own; the disorder usually emerges only when both are present in the same person. This interaction neatly explains the 48% twin concordance rate, the wide variation in age of onset, and why some individuals with high genetic risk never become ill. In contrast, others with apparently lower biological loading do. Physiological reductionism captures an essential part of the story, but the complete picture requires the broader, interactive perspective offered by the diathesis-stress / biopsychosocial model..

SUMMARY OF THE DOPAMINE HYPOTHESES

LATE 19th CENTURY – SYNTHETIC DYE ORIGINS

Phenothiazine was first synthesised in the 1880s as part of research into coal-tar-based dyes. Its three-ring structure — containing nitrogen and sulfur — made it chemically stable and capable of binding to fabrics. It was used primarily to produce blue and violet dyes.

EARLY 20th CENTURY – CHEMICAL SIMILARITIES NOTICED

By the 1930s, researchers began to note structural similarities between phenothiazine and biologically active compounds, such as methylene blue (derived from dye research and used to treat malaria and psychosis). This sparked interest in phenothiazine derivatives as potential therapeutic agents.

1937 – PROPAZINE AND OTHER DERIVATIVES

Initial phenothiazine derivatives such as propazine were tested for various medical uses, including antihistamine and antiemetic properties, but none had profound psychiatric effects at this stage.

1940s – RISE OF ANTIHISTAMINES

As the role of histamine in allergic responses became better understood, pharmaceutical companies began exploring phenothiazine derivatives for their antihistaminic properties. This led to the synthesis of promethazine in the mid-1940s by chemists at Rhône-Poulenc.

PROMETHAZINE (1947):

Promethazine was found to have potent sedative and anti-nausea effects in addition to its antihistamine function. It was used for surgical shock, motion sickness, and pre-operative sedation. Its ability to induce calmness and indifference, even in patients who were not anxious, caught the attention of Henri Laborit, a French military surgeon.

1950 – DEVELOPMENT OF CHLORPROMAZINE

Working with Rhône-Poulenc, Laborit tested various modifications of promethazine. One derivative — chlorpromazine(RP4560) — had notably stronger sedative and emotional blunting effects. It was initially marketed as a surgical anaesthetic enhancer, but psychiatrists quickly noted its striking impact on psychotic symptoms. It reduced delusions, hallucinations, and agitation, but its mechanism of action was unknown at the time.

PSYCHIATRIC USE AND RETHINKING THE BRAIN:

By 1952, chlorpromazine was being used as the first true antipsychotic. Its effects revolutionised psychiatry and led to the dopamine hypothesis, as researchers discovered it worked by blocking dopamine receptors — even though it was derived from a dye-based antihistamine

1958–1966: EARLY RESEARCH INTO DOPAMINE AND ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Haloperidol, developed in 1958, provided further evidence that neuroleptics act by blocking dopamine receptors. Researchers found that both Chlorpromazine and Haloperidol were dopamine antagonists, suggesting that dopamine overactivity might play a role in psychosis, particularly positive symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions.

1971–1975: DISCOVERY OF DOPAMINE RECEPTOR SUBTYPES

Scientists identified that dopamine receptors came in different types, including D1 and D2. D2 receptors were found to be particularly important in psychosis. This led to the idea that blocking D2 receptors could reduce positive symptoms of schizophrenia.

1979–1988: THE DOPAMINE HYPOTHESIS REFINED

New research showed that not all patients with schizophrenia had elevated dopamine activity, and not all responded to dopamine-blocking drugs. This led to refinements in the dopamine hypothesis, including the idea that different brain regions may be affected differently.

1990s: A SHIFT TO REGIONAL DOPAMINE IMBALANCES

Studies found that schizophrenia might involve both hyperdopaminergic (too much dopamine) in subcortical areas like the striatum — linked to positive symptoms — and hyperdopaminergic (too little dopamine) in the prefrontal cortex — linked to negative symptoms such as emotional flattening, lack of motivation, and cognitive deficits.

1999–2010: A MORE COMPLEX VIEW OF SCHIZOPHRENIA EMERGES

Researchers began to focus on how dopamine interacts with other neurotransmitters, including glutamate and serotonin. The glutamate hypothesis gained attention after it was found that NMDA antagonists like PCP and ketamine could induce both positive and negative symptoms.

2017–2021: UNDERSTANDING SCHIZOPHRENIA AT THE MOLECULAR LEVEL

Advanced brain imaging revealed the structure and function of dopamine receptors in unprecedented detail. Researchers discovered that receptor sensitivity and distribution varied among patients, explaining differential responses to medication. Theories increasingly emphasised neurodevelopment, circuit dysfunction, and molecular heterogeneity, rather than one-size-fits-all models.

ASSESSMENT

Jay has schizophrenia. His speech is rapid and confusing, constantly shifting from one idea to another. Jay’s father was treated for mental health problems when he was younger. Jay’s mother worries excessively about Jay. She often criticises his behaviour and tells him what to do. Jay’s doctor prescribes medication, which seems to reduce his symptoms.

WRITING ESSAYS

Discuss one or more explanations for schizophrenia. Refer to Jay in your answer. (16 marks: AO1 – 6, A02 - 4, AO3 – 6)

WORD COUNT GUIDELINES FOR AQA A-LEVEL PSYCHOLOGY RESPONSES

6-mark A01 response: ~225 words approx.

3-mark A01 response: ~112 words approx.

SIX-MARK A01 RESPONSE (APPROX. 225 WORDS)

The dopamine hypothesis is a neural correlate of schizophrenia, as it identifies dopamine imbalances in specific brain regions as a cause of symptoms. The original dopamine hypothesis suggested that positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, result from excess dopamine (hyperdopaminergic activity) in the mesolimbic pathway. This pathway connects the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens, a structure involved in reward and motivation. Overactivation of D2 receptors in this system disrupts standard information processing, leading to distorted perceptions and thoughts.

However, this model did not explain negative symptoms, such as apathy and cognitive dysfunction, prompting the reformulation of the dopamine hypothesis. This version proposes that negative symptoms arise due to too little dopamine (hypodopaminergic activity) in the mesocortical pathway. This connects the VTA to the prefrontal cortex, a region responsible for higher-order thinking, planning, and motivation. D1 receptors in the prefrontal cortex are excitatory, meaning they enhance brain activity, but dopamine underactivity in this pathway reduces prefrontal function, leading to persistent negative symptoms.

Since distinct patterns of dopamine dysfunction correspond to different symptom types, the dopamine hypothesis provides a biological explanation for schizophrenia. It is considered a neural correlate because it links specific brain abnormalities to the development of symptoms, helping to explain why schizophrenia presents with both excessive and diminished mental activity.

THREE-MARK A01 RESPONSE (APPROX. 112 WORDS)