THE EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

SPECIFICATION:

Students should demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the following research methods, scientific processes, and techniques for data handling and analysis; be familiar with their use; and be aware of their strengths and limitations.

THE EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

Types of experiments: laboratory

Types of experiments: field experiments

Types of experiments: Natural experiments

Types of experiments: Quasi-experiments.

Experimental designs: repeated measures, independent groups, matched pairs.

THE NON-EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

Observational techniques. Types of observation: naturalistic and controlled observation, covert and overt observation, and participant and non-participant observation. Observational design: behavioural categories, event sampling, time sampling

Self-report techniques, questionnaires, and interviews, both structured and unstructured. Questionnaire construction, including open and closed questions; interview design.

Correlations. Analysis of the relationship between co-variables. The difference between correlations and experiments.

Discourse analysis

Thematic analysis

Content analysis: analysis and coding.

Case studies

WHY DOES PSYCHOLOGY NEED RESEARCH METHODS?

Research serves as the foundational pillar for both the social sciences and sciences. Through research, theories and hypotheses can be tested and verified. In psychology, relying solely on personal arguments, beliefs, and observations is insufficient, as these are inherently biased and subjective, and often based on unrepresentative samples. Additionally, personal opinions are frequently influenced by individuals' desire to affirm preexisting political, religious, and moral agendas. Psychologists, therefore, are expected to approach their work without preconceived expectations or preferences, embracing the insights and conclusions drawn from empirical research. This objective stance enables the field to advance based on evidence and scientific inquiry rather than personal bias

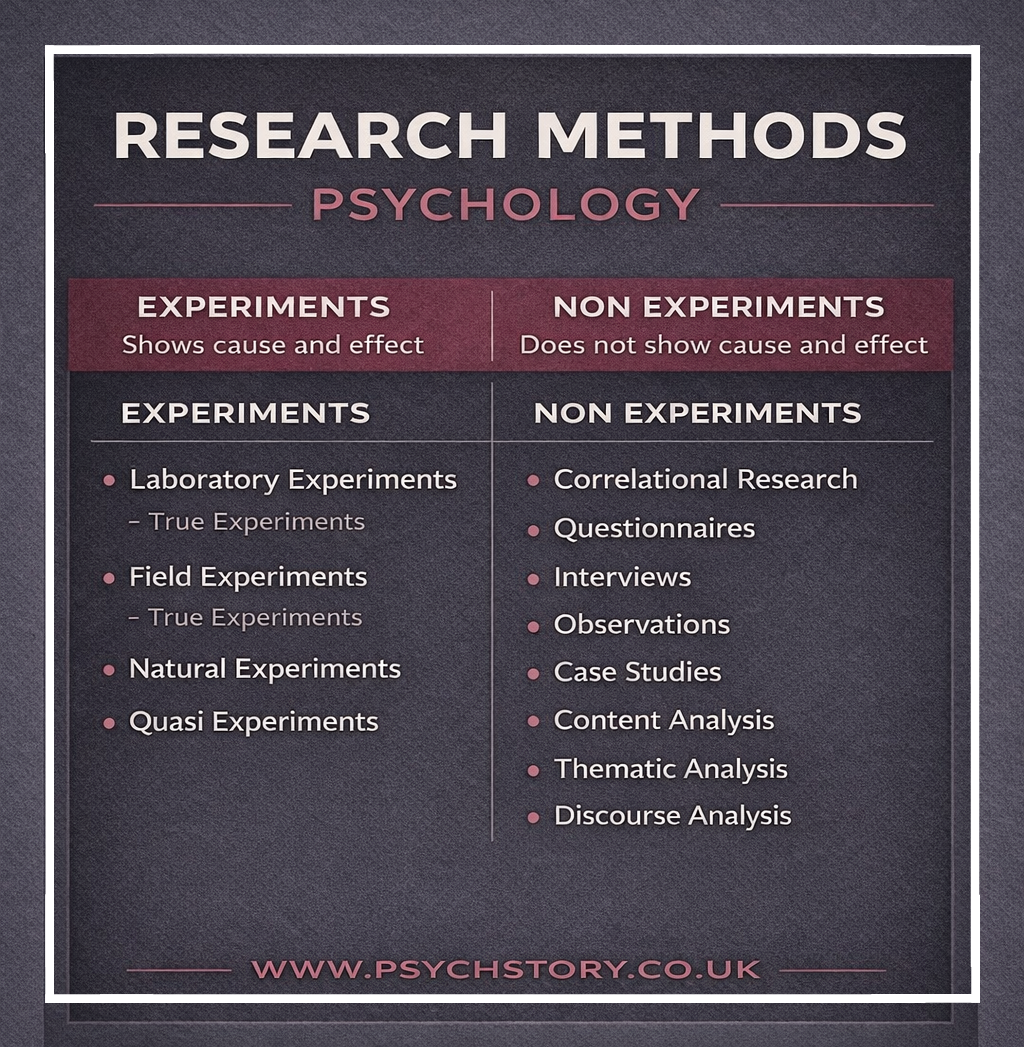

THE EXPERIMENT IS THE BEST RESEARCH METHOD

Research is divided into two categories: experimental and non-experimental, but experimentation is by far the most robust method.

.

ARE PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES ALL ABOUT COMMON SENSE?

In everyday life, people constantly try to make sense of others’ behaviour using what is often described as common sense. However, psychology differs from everyday explanations in important ways. Psychologists do not rely on intuition or anecdote. Instead, they study behaviour systematically, using the scientific method to collect objective, measurable data. Findings are tested through replication, and psychological theories must be open to being challenged or disproved. This distinguishes psychology as a science rather than a collection of personal opinions.

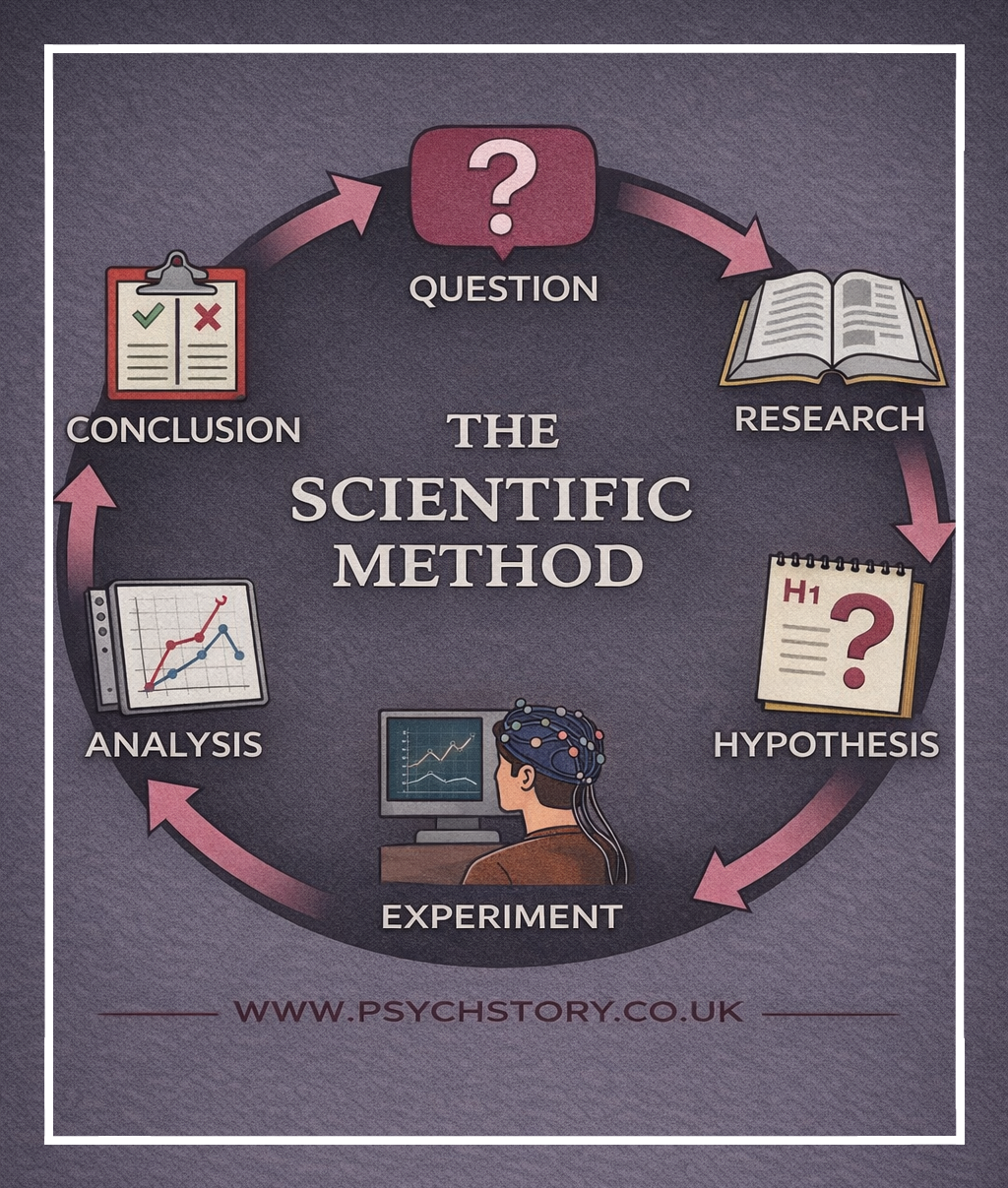

THE CYCLICAL NATURE OF THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Scientific research in psychology follows what is known as the research process. This process is cyclical, meaning it does not have a clear end point.

The stages of the research process typically include:

Review previous research and theories

→ Form a hypothesis

→ Design a study

→ Conduct the research

→ Analyse and report findings

→ Add to, revise, or reject existing theories

As new findings are produced, they contribute to the existing body of knowledge. This may lead to theories being refined, expanded, or replaced. The process then begins again as new questions are generated

EXPERIMENTS

The experiment is pivotal in the psychologist's arsenal, distinguished as the sole scientific method capable of uncovering causal relationships—the underlying causes of behaviours. To achieve this, an experiment requires manipulating the independent variable while meticulously controlling for extraneous variables in a controlled setting. This methodological rigour ensures that any observed changes in the dependent variable can be directly attributed to the manipulation of the independent variable, thereby providing concrete insights into cause-and-effect dynamics in psychological research.

WHAT IS A TRUE EXPERIMENT?

In experimental research, there are various types of experiments: Laboratory, Field, Natural, and quasi-experimental. However, only laboratory and Field experiments are commonly recognised as "true experiments" due to their rigorous design and ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships. The following rules characterise these true experiments:

RULE ONE:

Conducting a “true experiment” stipulates the necessity of having at least two conditions, meaning that participants must engage in distinctly different activities. A scenario in which all participants are subjected to the same condition, such as being asked to lend money on a high street, does not qualify as an experiment because it lacks experimental variability (there is only one condition). To transform this scenario into a genuine experiment, one could introduce variation by asking one group of participants to lend money during rainy weather and another during sunny weather. This variation creates two distinct conditions: solicitation under sunny and rainy conditions. The introduction of this second condition is crucial to the foundation of experimental research, as it enables essential comparisons for drawing cause-and-effect conclusions. Without this comparative basis, the experimental design is incomplete and cannot adequately explore the causal relationships between variables.

In more technical terms, social scientists refer to different conditions in an experiment as independent variables (IVs). Therefore, it's crucial to articulate the foundational rule of experimental design with the appropriate terminology for clarity and precision. An experiment must include at least one independent variable (IV) and a control condition, ensuring that participants engage in at least two distinct activities.

This requirement can manifest in several forms, including:

There are at least two independent variables (IVs); for example, participants might listen to music by Mozart or Bach while completing an IQ test (the dependent variable or DV).

A scenario with one IV and a control condition, such as participants listening to Mozart or experiencing silence while completing an IQ test (the DV).

In a design incorporating multiple IVs and a control condition, participants might listen to Mozart, Bach, Beethoven, or no music while completing an IQ test (the DV).

Crucially, every experiment must also identify a dependent variable (DV), the outcome or effect measured to assess the impact of the independent variable(s). This structure allows for a precise examination of how variations in the IV(s) influence changes in the DV, facilitating a robust analysis of cause-and-effect relationships

RULE TWO:

In experimental research, the dependent variable (DV) is the outcome measured to assess the impact of the independent variable(s) (IVs). It is the outcome or effect that researchers are interested in examining, specifically how it changes in response to manipulations of the IV. This relationship allows for a precise investigation of cause-and-effect dynamics within the study.

For example, consider a hypothesis stating that consuming cheese before bedtime leads to nightmares. In this scenario, the IV would be the consumption of cheese, and the DV—the measured result—would be the occurrence of nightmares. Researchers would manipulate the IV by having some participants consume cheese before sleep. In contrast, others do not and then measure the DV by recording the frequency or intensity of nightmares experienced by participants. This structure highlights how variations in the IV (cheese consumption) directly influence changes in the DV (nightmares), facilitating a robust analysis of the hypothesised cause-and-effect relationship.

RULE THREE:

To accurately infer a cause-and-effect relationship in experimental research, it is crucial to control or eliminate all variables other than the independent variable (IV). Failure to do so can lead to results being influenced by extraneous variables (EVs) or confounding variables, compromising the study's validity.

Take, for example, a scenario in which a research student conducts a study in which participants rate the attractiveness of photographs of the opposite sex. If the student overlooks the need for uniformity in the photographs, resulting in some images featuring smiling individuals while others depict bored or unfriendly expressions, the study's outcomes could be skewed. Instead of measuring facial attractiveness, the ratings may inadvertently reflect perceptions of friendliness or approachability because of variation in expressions. This oversight demonstrates how uncontrolled extraneous variables, such as the presence or absence of a smile, can invalidate research findings, as the observed effect might not be due to the intended IV but instead to these unaccounted-for factors.

RULE FOUR

For an investigation to qualify as a “true experiment”, the researcher must actively manipulate the independent variable (IV)—that is, they must introduce or modify the IV to observe its effect on the dependent variable (DV). In contrast, if the IV occurs naturally without the researcher's intervention, the study is classified as a 'natural experiment.' Natural experiments leverage real-world events, such as natural disasters, to study their impact on individuals or communities.

A prime example of a natural experiment is the examination of panic attack prevalence among New Yorkers before and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The 9/11 event, serving as the IV, was not orchestrated by researchers; it was an unforeseen tragedy that occurred independently of any scientific study. Because it is impossible to reproduce such events for research purposes and because researchers cannot control extraneous variables or participant assignment in the context of natural disasters, natural experiments offer less certainty in establishing cause-and-effect relationships than true experiments. The inherent lack of control over the IV and other confounding factors means that, while natural experiments can provide valuable insights, they are not classified as true experiments because of these limitations.

RULE FIVE

In a “true experiment”, participants (PPs) must be randomly allocated to different conditions. This random allocation ensures that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any of the study's conditions, thereby safeguarding against selection bias and ensuring group comparability. Without random allocation, the study might be categorised as a quasi-experiment, which, while still valuable, lacks the random assignment feature that helps establish stronger causal relationships.

The Stanford prison experiment conducted by Philip Zimbardo serves as a prominent example to illustrate the importance of random allocation in experimental design. In this study, participants were randomly assigned to either the role of a prisoner or a prison guard. This methodological choice was crucial for the experiment's integrity, as it ensured that any participant could end up in either role, independent of their physical size, personality, or other characteristics. This randomisation process eliminates potential selection bias, allowing for more credible conclusions. The absence of bias in the allocation process means that the observed differences between the prisoner and guard groups can be more confidently attributed to the effects of the experimental conditions rather than to pre-existing group differences. Hence, the random allocation in Zimbardo's study is a key factor contributing to the believability and validity of the results.

TYPES OF EXPERIMENT

LABORATORY, FIELD EXPERIMENTS, NATURAL AND QUASI-EXPERIMENTS

Laboratory, field, natural and quasi-experiments all investigate relationships between variables by comparing groups of scores. Still, there are significant differences among types of experiments, such as their perceived respectability.

Laboratory experiments fulfil all the criteria of an actual experiment but have problems with external validity.

Field experiments are true but don't occur in a controlled environment or have random allocation of participants.

Natural and quasi-experiments cannot establish causation with the same confidence as a lab experiment.

Natural experiments don't manipulate the IV; they observe changes in a naturally occurring IV.

Quasi-experiments don't randomly allocate participants to conditions.

LABORATORY EXPERIMENT

Definition: Experiments conducted in controlled, artificial settings where researchers manipulate an independent variable (IV) and measure its effect on a dependent variable (DV).

Advantages:

Control over extraneous variables: The controlled environment enables researchers to isolate variables and ensure that changes in the DV are attributable solely to the IV.

Easy replication: Standardised procedures ensure that other researchers can repeat the study to verify reliability.

Precision: Technical equipment and controlled conditions enable accurate measurement of variables.

Causal relationships: High control helps establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Disadvantages:Internal validity threats: demand characteristics (participants anticipate the aim and alter behaviour), social desirability bias (participants respond favourably), the Hawthorne effect (behaviour changes due to being observed), and investigator effects (researcher influence on outcomes).

External validity threats: Low ecological validity (does not reflect real-life settings), low mundane realism (tasks are artificial), and limited generalisability to real-world contexts.

Ethics: Ethical considerations typically include obtaining informed consent, providing debriefing, and ensuring the right to withdraw. Some studies may involve deception, which must be justified and addressed during debriefing. Vulnerable populations require extra safeguards.

Examples: Milgram’s study on obedience to authority; Loftus and Palmer’s research on eyewitness testimony; Stroop effect studies investigating reaction times to congruent and incongruent word-colour pairings.

FIELD EXPERIMENT

Definition: Experiments conducted in real-world settings where researchers manipulate the IV and measure the DV in participants' natural environment.

Advantages:

High ecological validity: Behaviour is observed in a real-life context, thereby increasing the generalisability of the findings.

Reduced demand characteristics: Participants may be unaware they are part of an experiment, leading to more authentic behaviour.

Insight into natural behaviour: Captures how people behave outside artificial conditions.

Disadvantages:Lack of control: Extraneous variables are harder to manage, making it difficult to isolate the effect of the IV.

Replication challenges: Real-world settings are dynamic and hard to replicate.

Uncontrolled participant variables: Differences among participants can confound results.

Ethical issues: Participants may not be aware of their involvement, raising concerns about consent and deception.

Ethics: Deception and lack of informed consent are common in field settings. Debriefing is essential when participants are unaware of their participation. Researchers must avoid harm and ensure confidentiality.

Examples: Studying helping behaviour in a public setting, inspired by the bystander effect; investigating productivity changes in an office when lighting conditions are altered.

QUASI-EXPERIMENTS

Definition: Experiments where participants are not randomly assigned to conditions, and the independent variable (IV) is a pre-existing characteristic of the participants (e.g., gender, socioeconomic status).

Advantages:

Practical application: Allows researchers to study variables that cannot be manipulated ethically or practically (e.g., natural disasters, age, or education).

High ecological validity: Often conducted in real-world settings.

Natural comparisons: Enables research into pre-existing groups, providing valuable insights into naturally occurring differences.

Disadvantages:Causality issues: The lack of random assignment makes it harder to establish causal relationships.

Bias risks: Pre-existing differences between groups may confound results.

Limited control: Real-world settings often introduce extraneous variables that cannot be controlled.

Ethics: Typically ethical, as researchers do not manipulate groups. Informed consent may still be required depending on the context. Studies involving vulnerable groups or sensitive topics require special ethical consideration.

Examples: Investigating the effects of government policy changes on public health; studying differences in mental health outcomes between survivors of a natural disaster and unaffected populations.

NATURAL EXPERIMENT

Definition: Observational experiments where researchers take advantage of naturally occurring IVs without manipulation.

Advantages:

Ecological validity: Observations occur in real-life settings, making findings highly generalisable.

Unethical variables: Allows study of topics that would be unethical to manipulate (e.g., trauma, disasters).

Unobtrusive observation: Reduces demand characteristics and provides authentic behavioural insights.

Disadvantages:No control over variables: Researchers cannot manipulate the IV, making it difficult to isolate its effect.

Replication challenges: Natural settings are unique and often non-replicable.

Causality issues: Correlation rather than causation is often inferred due to a lack of control.

Unpredictable occurrence: Events of interest may be rare or happen unexpectedly, limiting research opportunities.

Ethics: Ethical if non-intrusive and informed consent is obtained where possible. Observational studies must avoid harm and respect confidentiality. Consent is not always feasible in emergencies, but it requires justification.

Examples: Studying the psychological effects of a natural disaster on survivors; investigating the societal impact of legislative changes, such as the introduction of a public smoking ban.