MEMORY A’LEVEL

THE TOPIC OF MEMORY IS PART OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

Many students are confused because the AQA A-level specification states that Paper 1 begins with the four core topics (Social, Memory, Attachment, Psychopathology). In contrast, Paper 2 introduces the Approaches (cognitive, biological, psychodynamic, behaviourist, etc.). Edexcel is better here.

So when you first study Memory in Year 12, the word “cognitive approach” hasn’t been officially taught yet (unless, of course, your teacher taught you approaches first).

Not knowing that memory is part of the cognitive approach means that you don’t recognise its core features, assumptions, treatments and methods of research. As with any approach, understanding it thoroughly means you can apply it across any topic, not only AQA topics, but any cognitive topic. This means you don’t have to learn each topic by rote, but rather clarify the logic and apply it across disciplines.

WHY YOU NEED TO KNOW THIS FROM THE OFFSET

Every single approach in psychology has its own:

Core assumptions about human behaviour

Particular research methods

Typical strengths & weaknesses (evaluation points)

Links to issues & debates (e.g. reductionism, determinism, nature/nurture)

Once you learn the “template” for the cognitive approach, you can reuse the same evaluation points in many different topics across the two years: Memory, Attachment (cognitive explanations, internal working models), Psychopathology (cognitive explanations of depression, OCD, phobias), Schizophrenia (cognitive explanations), Forensic (cognitive interview, cognitive explanations of offending)

INTRODUCTION TO PSYCHOLOGY AND ITS APPROACHES

Psychology is not a single belief system but a collection of approaches that explain human behaviour in different ways. Each offers a distinct perspective on what drives our thoughts, emotions and actions.

The earliest major approach was the psychodynamic perspective, which argued that unconscious processes shaped by early experience influence behaviour. It highlighted the depth and complexity of human motivation, but was criticised for lacking scientific testability.

Behaviourism followed as a deliberate rejection of psychoanalytic ideas. By focusing only on observable behaviour, it introduced rigorous experimental methods and helped establish psychology as an empirical discipline. However, its insistence on studying only what can be measured created two key limitations: it overlooked internal mental processes and could not fully explain human cognition, language or reasoning:

BIRTH OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

While behaviourism remains relevant—especially for understanding how reinforcement, punishment and associative learning shape behaviour—it accounts for only part of human experience. Its focus on the environment cannot explain the higher cognitive capacities that distinguish human thought.

The limits of behaviourism led directly to the rise of the cognitive approach. This perspective set out to examine the processes behaviourism ignored: how we attend to information, store it, retrieve it, use language, recognise faces, make decisions and remain conscious of our own thinking. The cognitive approach investigates the mechanisms underlying behaviour, asking what we do, why we do it and how mental activity is generated.

THEORETICAL MODELS

In cognitive psychology, a theoretical model is simply a way of explaining how the mind works by breaking complex processes—such as memory—into smaller, understandable parts. Because psychologists cannot open the brain and observe thinking or memory unfold in real time, they construct models to determine what the “components” of a system might be and how they function.

For example, a central question in memory research is whether memory is a unitary system (a single store with no distinction between short-term and long-term memory) or a multi-component system in which STM and LTM are separate and function differently. Models help to answer questions such as:

• How do the components interact?

• What happens to the system if one part is damaged?

• How does one cognitive system—such as memory—interact with others, such as language, attention, or perception?

These models are not literal pictures of the brain. They are simplified diagrams or descriptions that illustrate what occurs within the mind and in what order. For students, they serve as a map, clarifying processes that would otherwise be invisible.

HOW COGNITIVE SYSTEMS WORK TOGETHER

Cognitive systems function as networks and never operate in isolation. , with each component interacting with others to perform complex tasks. For example:

Memory and language interact when a person answers a question or explains an idea. Information must first be retrieved from long-term memory, then organised and expressed through the language system. The response appears fluent only because both processes are operating in coordination.

Attention and perception combine when someone recognises a familiar face in a crowd. Attention directs the mental spotlight toward relevant features, while perceptual processes interpret shapes, colours and spatial relationships to identify the person.

Decision-making and problem-solving rely on stored knowledge and present awareness. When choosing the best route to a destination or deciding how to tackle a practical task, the individual draws on memory, focuses attention on relevant details, and evaluates available options.

Although these interactions seem automatic, theoretical models slow them down, decompose the components, and show how they fit together. This helps psychologists investigate the processes scientifically and clarifies what the mind is doing “behind the scenes” during even the simplest behaviours.

THE MIND-AS-COMPUTER METAPHOR

The mind-as-computer metaphor is a central idea within cognitive psychology. It frames the mind as an information-processing system whose operations can be understood by analogy with a computer. Importantly, not all cognitive psychologists accept the metaphor literally. Some treat it simply as a modelling tool that helps explain mental processes, whereas others argue that, in functional terms, human cognition is computational.

According to this view, both humans and computers rely on structured, rule-governed systems. They encode information, store it, manipulate it, and generate output. Both use networks of associations to organise knowledge: computers through data structures and algorithms, humans through semantic networks. The point is not that computers “think like humans”, but that many operations humans perform are computational in nature.

The metaphor emphasises that cognition follows fixed procedures rather than free-floating intuition. Human behaviour depends on the state of the underlying system. If memory circuits are damaged, memory fails. If perceptual mechanisms are disrupted, perception fails. In that sense, humans behave like “wet robots”: biological organisms whose thoughts and actions are determined by the functioning of their physical architecture.

Of course, computers lack emotions, but this is a matter of evolutionary design, not a conceptual impossibility. Emotions evolved to support survival and sexual reproduction; a machine that was never shaped by natural selection would not possess such mechanisms. The metaphor, therefore, remains helpful in highlighting the structural similarities between computational systems and human cognition, without claiming that the two are identical in every respect.

The mind-as-computer metaphor does not explain everything — especially the social, emotional and embodied aspects of human experience — but it remains one of the most influential frameworks for understanding how information is processed, stored and used in the human mind.

COGNITIVE RESEARCH METHODS

COGNITIVE RESEARCH METHODS

Cognitive psychologists employ four primary research methods to investigate how the brain processes mental functions such as memory and language. The choice of methods often depends on the technological advances of the time. For instance, in 1968, when scanning technologies such as fMRI and PET did not exist, Atkinson and Shiffrin had to rely on less advanced techniques to explore how memory might be organised in the brain.

To understand why these methods became central, it is helpful to consider the context in which cognitive psychology developed.

Behaviourism had insisted that the mind could not be studied because it could not be observed. The brain was treated as a black box: psychologists could only measure what went in and what came out (i.e., stimuli and responses). Psychoanalysis made the opposite claim: the workings of the mind could be accessed, but only through the therapist’s interpretation of the unconscious. Neither approach provided a scientific means of examining the internal processes underlying thinking, memory, or language.

Cognitive psychologists in the 1960s sought to understand what the brain was doing between input and output, but they faced a practical obstacle: they could not observe the living brain. As a result, they had to rely on the tools available at the time – experiments, behavioural tasks, case studies of brain injury, memory errors, and laboratory manipulations that allowed them to infer the structure of mental processes indirectly.

As technology advanced, the discipline advanced with it. Developments in computer science have introduced new ways of modelling how information is processed, stored, and retrieved. Later, medical imaging techniques (such as CT, PET and eventually fMRI) made it possible to observe the activity of healthy and damaged brains in real time, giving psychologists a biological window into systems that previously had to be inferred.

Against this background, the four core research methods of cognitive psychology developed and remain central today. They reflect the historical progression from “we cannot see inside the brain” to “we can now measure its activity”, while preserving the original aim of understanding the internal processes that produce human behaviour.

The four methods commonly used to investigate inner mental processes are:

COGNITIVE RESEARCH METHODS

Experimental cognitive psychology: essentially testing cognitive processes by doing laboratory experiments and, to a lesser extent, field and natural experiments. Cognitive psychologists mostly conduct controlled lab experiments to study mental processes scientifically. These "fair tests" manipulate an Independent Variable (IV) to observe its effect on a Dependent Variable (DV). A famous example is Baddeley's encoding experiment, which investigated how STM and LTM encode information differently. Laboratory experiments are essential for testing hypotheses about how cognitive processes work under controlled conditions.

Cognitive neuropsychology.Postmortem Studies and functional imaging of Brain-Damaged Individuals: Cognitive neuropsychologists examine the brains of individuals who sustained brain damage during their lifetimes to understand how specific cognitive functions are affected. Post-mortems were the only method before imaging techniques. A classic example is Paul Broca's study of Tan, in which postmortem analysis revealed damage to Broca’s area, which is associated with speech production. This early form of investigation laid the groundwork for understanding the relationship between brain areas and behaviour. Over time, as technology improved, brain scans provided more dynamic and real-time insights, leading to the development of cognitive neuropsychology.

Cognitive neuroscience (fMRI, PET, EEG): This method involves scanning the brains of healthy individuals while they engage in specific cognitive tasks. Advanced techniques such as fMRI and PET scans enable researchers to identify which brain regions are active during processes such as memory recall, language comprehension, or problem-solving. For instance, imaging studies indicate that Short-Term Memory (STM) and Long-Term Memory (LTM) are processed in different brain regions.

Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence (AI) Models: Building computer models of mental processes. The aim is to simulate human cognitive processes by developing AI models that replicate brain function. Cognitive scientists can learn more about how the brain functions by replicating processes like memory storage, problem-solving, and language use. This approach helps bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and practical application by providing insights into how cognitive processes might be structured and work together.

KEY ISSUES AND DEBATES

DETERMINISM VERSUS FREE WILL: soft determinism (we have some conscious control over thinking)

NATURE VERSUS NURTURE: leans towards the nature side (schemas can be innate), but experience builds them

IS THE COGNITIVE APPROACH SCIENTIFIC? Yes – it uses laboratory experiments, scans and replicable methods.

IS THE COGNITIVE APPROACH REDUCTIONIST: Yes – it reduces complex behaviour to simple cognitive processes.

EXAM TIP

Whenever a question asks you to evaluate a memory study (or any cognitive explanation), you can use points from the mental approach template above, and the examiner will love you for it.

ASSESSMENT

Which approach rejects the idea that internal mental processes can be studied because they cannot be directly observed?

a. Behaviourist

b. Cognitive

c. Psychodynamic

d. HumanisticWhich development directly contributed to the rise of the cognitive approach?

a. Advances in psychoanalytic therapy

b. Computer science and information-processing models

c. Increased use of naturalistic observation

d. The decline of laboratory researchThe cognitive approach primarily argues that human behaviour is understood by studying:

a. Reinforcement histories

b. Unconscious conflict

c. Internal mental processes

d. Genetic inheritanceIn the Multi-Store Model, which question reflects the move away from a unitary view of memory?

a. Memory is located in one area of the brain.

b. STM and LTM operate as separate systems?

c. There are no different types of memory.

d. Damage to memory results in total memory loss.Which statement best describes a theoretical model in cognitive psychology?

a. A literal map of the brain

b. A diagram/model that breaks a mental process into its component parts and shows how they interact with other cognitive systems.

c. An explanation for internal processes.

d. A summary of case studiesWhich pair shows two cognitive systems working together?

a. Conditioning and imitation

b. Memory retrieval and language production

c. Genetics and evolution

d. Unconscious and conscious conflictWhich example best fits the mind-as-computer metaphor?

a. Random emotional responses

b. Dreams reflecting hidden wishes

c. Information input, processing, storage and output

d. Behaviour shaped only by punishmentWhich method did cognitive psychologists rely on before brain-imaging technology existed?

a. PET scanning

b. fMRI tasks

c. Case studies of brain injury

d. Event-related potentialsWhich development allowed psychologists to observe cognitive processes in real time?

a. Introspection

b. Operant conditioning chambers

c. fMRI and PET

d. HypnosisOdd one out:

Which option does not belong with the four primary methods used in cognitive psychology?

a. Cognitive neuroscience

b. Cognitive neuropsychology

c. Laboratory experiments

d. Dream interpretation

KEY WORDS FOR MEMORY

SENSORY REGISTER/MEMORY (ICONIC, ECHOIC, HAPTIC, OLFACTORY, GUSTATORY):

The Sensory Register is the initial stage of memory that captures sensory information from the environment for a brief period. It includes:

Iconic Memory: Visual sensory memory (images and visual stimuli).

Echoic Memory: Auditory sensory memory (sounds).

Haptic Memory: Tactile sensory memory (touch).

Olfactory Memory: Memory for smells.

Gustatory Memory: Memory for tastes.

SHORT-TERM MEMORY (STM): Short-term memory refers to the temporary storage of information that is actively being processed. It typically holds a limited amount of information (around seven items) for a short duration (approximately 18-30 seconds).

LONG-TERM MEMORY (LTM): Long-term memory (LTM) is the continuous storage of information that can last from a few minutes to an entire lifetime. It has a much larger capacity than STM and can store various types of information (e.g., declarative, procedural).

TRANSFER OF STM TO LTM: The process through which information moves from Short-Term Memory to Long-Term Memory. This typically requires rehearsal and encoding, where information is processed deeply enough to be stored for the long term.

FORGETTING THROUGH RETRIEVAL FAILURE: A forgetting that occurs when information is stored in Long-Term Memory but cannot be accessed. Retrieval failure often occurs due to a lack of retrieval cues or context.

LINEAR DIRECTION: In the context of memory models, a linear direction refers to the sequential process by which information moves through different memory stores—first to the sensory register, then to STM, and finally to LTM.

FORGETTING THROUGH DISPLACEMENT: Forgetting Through Displacement occurs when new information pushes out older information from Short-Term Memory due to its limited capacity.

UNITARY STORE: A Unitary Store is a memory model that posits a single, undifferentiated store rather than separate types (e.g., no division between STM and LTM).

MULTIPLE STORES: In contrast to a unitary store, Multiple Stores refer to models of memory that suggest distinct types of memory storage (e.g., Sensory Memory, Short-Term Memory, and Long-Term Memory), each with different characteristics.

REHEARSAL LOOP: The Rehearsal Loop is the process of repeatedly mentally repeating or verbalising information to keep it in Short-Term Memory or to transfer it to Long-Term Memory.

ENCODING: Encoding is the process of transforming sensory input into a form that can be stored in memory. It is how information is prepared for storage in either Short-Term or Long-Term Memory.

CAPACITY: Capacity refers to the amount of information that can be held in a particular memory store. For instance, STM has a limited capacity (around 7 items), whereas LTM is thought to have a virtually unlimited capacity.

DURATION: Duration is the length of time information can be stored in a memory system. For example, STM has a short duration of around 18-30 seconds, whereas LTM can retain information for a much longer time, potentially a lifetime.

ACOUSTIC ENCODING: Acoustic Encoding is the process of converting information into sound patterns for storage in memory, often used in STM.

SEMANTIC ENCODING: Semantic Encoding is the encoding of information by its meaning, thereby facilitating recall. This type of encoding is more common in LTM.

VISUAL ENCODING: Visual Encoding is the process of converting visual information (e.g., images, colours) into a memory trace for storage. This type of encoding is often used in both sensory memory and STM.

AMNESIA: Amnesia is a condition characterised by a significant loss of memory, often affecting one’s ability to remember past events (Retrograde Amnesia) or form new memories Retrograde Amnesia).

Causes:

Brain injury Anterograde Amnesia (e.g., concussion).

Neurological conditions (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease).

Psychological events (e.g., extreme stress or trauma).

ANTEROGRADE AMNESIA: Anterograde Amnesia is the inability to form new memories after the onset of an amnesia-causing event. While a person can still recall past events, they struggle to retain new information.

Causes:

Damage to the hippocampus or related brain areas (often due to traumatic brain injury, stroke, or certain drugs/alcohol abuse).

Diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease affect the brain's memory system.

RETROGRADE AMNESIA: Retrograde Amnesia is the loss of access to memories that were formed before the onset of the amnesia-causing event. It can affect recent memories or even older ones, depending.

Causmemories:

Traumatic brain injury (e.g., concussion, surgery).

Psychological trauma or events leading to memory repression.

Neurological damage (from conditions like encephalitis or Alzheimer’s disease).

MEMORY FAILURES AND CAUSES

DISPLACEMENT: The process where new information pushes out older information from Short-Term Memory (STM) because of its limited capacity.

Cause: Occurs frequently when attempting to memorise many items simultaneously, leading to forgetting earlier items.

TRACE DECAY: The loss of memory if it is not accessed or rehearsed. Trace Decay is a theory of forgetting in which memory traces (the physical changes in the brain that represent memories) fade and weaken over time when they are not actively rehearsed or used.

Cause: Natural degradation of memory traces in both Short-Term and Long-Term Memory.

RETRIEVAL FAILURE: The inability to access a memory that is stored in Long-Term Memory (LTM), often due to insufficient cues or lack of context.

Cause: Sometimes known as the "tip-of-the-tongue" phenomenon, it can occur due to insufficient rehearsal or improper encoding, making the memory hard to retrieve when needed

AQA MEMORY SPECIFICATION:

TYPES OF MEMORY: Sensory Register, Short-Term Memory and Long-Term Memory.

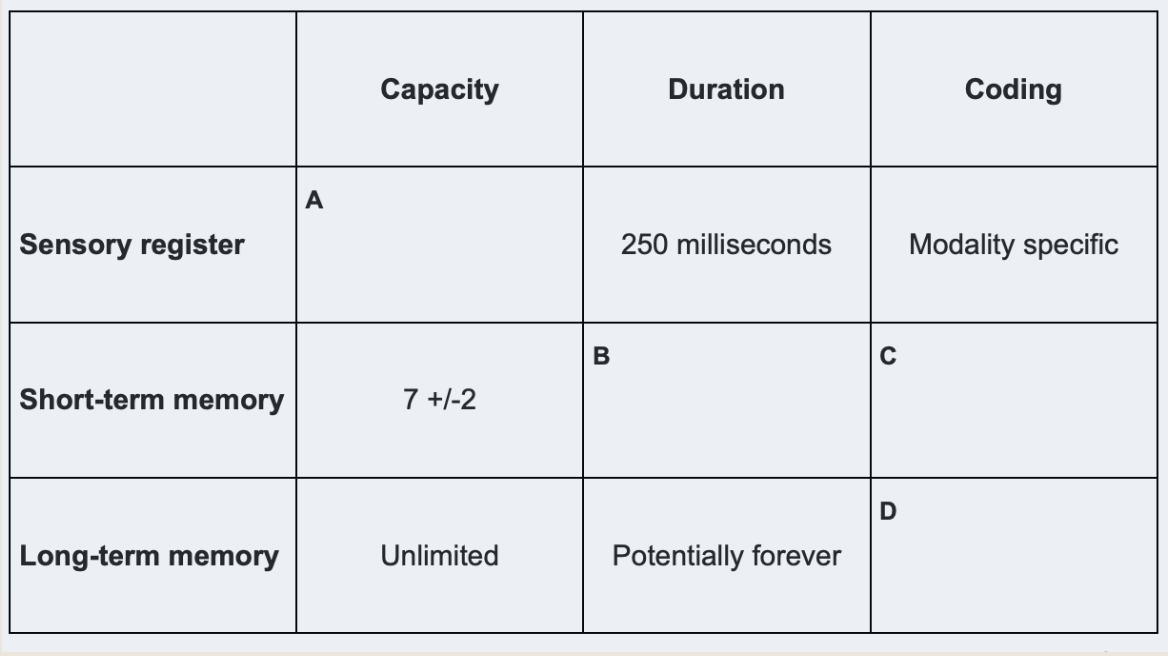

FEATURES OF EACH MEMORY STORE: Coding, Capacity and Duration.

MODELS OF MEMORY: The Multi-Store Model of Memory

TYPES OF LONG-TERM MEMORY: Episodic, Semantic, Procedural.

MODELS OF MEMORY: The Working Memory Model – including The Central Executive, Phonological Loop, Visuo-Spatial Sketchpad and Episodic Buffer. Features of the model: coding and capacity.

EXPLANATIONS FOR FORGETTING: Proactive and Retroactive Interference and Retrieval Failure due to the absence of cues.

FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY: Misleading Information, including Leading Questions and Post-Event Discussion

FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY: Anxiety.

IMPROVING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY: The Cognitive Interview

INTRODUCTION TO THE TOPIC OF MEMORY

A key focus in introductory courses in cognitive psychology is the study of memory, with many courses and specifications examining the Multi-Store Model (MSM) of memory proposed by Atkinson and Shiffrin. The MSM is often studied because it was the first comprehensive model to describe how memory operates, providing students with ample opportunity for positive and negative critiques.

Before Atkinson and Shiffrin's work, memory was primarily seen as a singular, unitary system. However, they hypothesised that memory is not a single entity but comprises three distinct stores: the Sensory Register, Short-Term Memory (STM), and Long-Term Memory (LTM). This idea revolutionised our understanding of how we encode, store, and retrieve information, laying the foundation for modern memory research.

With this background, we will begin our exploration of memory research by examining how theories such as the Multi-Store Model challenged traditional views of memory and paved the way for new approaches to understanding cognition and the brain. But first, we need to have some subject-specific terminology:

TYPES OF MEMORY: SENSORY REGISTER, SHORT-TERM MEMORY AND LONG-TERM MEMORY

ATKINSON AND SHIFFRIN’S THREE TYPES OF MEMORY STORES

According to Atkinson and Shiffrin’s Multi-Store Model, memory comprises three distinct stores: the Sensory Register, Short-Term Memory (STM), and Long-Term Memory (LTM). Each store plays a unique role in processing and storing information.

SENSORY REGISTER

SM: The Sensory Register is an unconscious memory store that briefly holds sensory information from the environment, creating an unconscious representation of our world. It constantly receives input from all our senses (e.g., sight, sound, touch).

You are typically unaware of this information unless you pay attention. For instance, you may not notice how your foot feels until you suddenly step on a pin. This sensation captures your attention, moving the information from the sensory register to STM, where it becomes conscious.

SHORT-TERM MEMORY (STM)

STM is the period during which information that has received attention is brought to conscious awareness and actively processed. At this stage, the stimuli become something we can think about or temporarily hold in our minds.

LONG-TERM MEMORY (LTM)

LTM stores information over extended periods, sometimes for a lifetime. It encodes information based on meaning—a process known as semantic encoding—which allows for deeper processing and long-term retention.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE STORES: FEATURES OF EACH MEMORY STORE.

To support their theory—that memory is not one store but three—Atkinson and Shiffrin had to demonstrate that STM, sensory memory (SM), and LTM differ fundamentally, including in their brain locations. The most common way to explain these differences is to compare them with respect to duration, capacity, and encoding. Understanding these distinctions reinforces the idea that memory comprises three distinct, interconnected stores.

CAPACITY IN MEMORY STORES

Capacity refers to the amount of information that each memory store can hold. STM has a limited capacity, whereas LTM is thought to have far greater capacity, potentially unlimited.

STM Capacity - Miller’s Study (1956): George Miller investigated STM capacity and found that people can generally hold approximately 7 ± 2 items at a time (often referred to as "the magic number seven"). This suggests that STM has limited capacity, necessitating techniques such as chunking (grouping information) to maximise storage.

MEMORY SPAN/DIGIT SPAN: Memory span, often assessed through digit span tasks, is the capacity of working memory to hold a sequence of items, typically numbers, in the correct order for a short period. A classic digit span task involves a person listening to or reading a series of numbers and then repeating them in the same order. The number of items that can be correctly recalled without mistakes is considered their "digit span."

Typical Span:

Research, like that of George Miller, suggests that the average person’s memory span is about 7 ± 2 items (between 5 and 9), meaning this is the usual limit for the number of discrete units or chunks one can hold in short-term memory (STM).

CHUNKING AND STM CAPACITY: Chunking is a strategy for overcoming the limited capacity of STM by grouping individual bits of information into larger, meaningful units, or "chunks." This allows for more efficient use of memory resources, enabling one to remember more items than by storing each item separately.

Example: Instead of trying to remember the digits "1, 9, 4, 5," which could be four separate items, one might chunk them into the year "1945." This transformation reduces the number of items from four to one.

Significance: Chunking extends STM capacity by grouping information into meaningful units. A well-known example is how people often remember phone numbers in chunks (e.g., 123-456-7890).

DURATION IN MEMORY STORES

Duration refers to the period during which information can be retained in a memory store without being lost or forgotten.

STM Duration - Peterson and Peterson (1959): Peterson and Peterson studied the duration of STM by presenting participants with trigrams (nonsense sequences of three consonants, such as "JRG") to remember while counting backwards to prevent rehearsal. They found that STM was unable to retain the information after just 18-30 seconds, showing that STM duration is very short without rehearsal.

LTM Duration - Bahrick et al. (1975): Bahrick and colleagues examined the duration of LTM by asking participants to recall names and faces from their high school yearbooks. They found that even years later—up to 50 years—people could remember about 70% of their classmates' names and faces, suggesting that LTM has a long duration, potentially lasting a lifetime.

UNDERSTANDING ENCODING IN STM AND LTM

Many students find the concept of encoding challenging. Put, encoding is how information is transformed and stored in our memory systems—Short-Term Memory (STM) and Long-Term Memory (LTM). However, the way we encode information in each system differs:

STM encodes acoustically and visually, meaning it primarily stores sounds and images. For instance, if you're trying to remember a phone number briefly, you might repeat it aloud (acoustic encoding) or visualise the digits (visual encoding).

LTM, however, encodes information semantically, meaning it stores the meaning rather than the exact details.

SEMANTIC VS. SYNTAX EXAMPLE

To understand semantic encoding, let's compare it with syntax.

Syntax refers to the exact structure of words and sentences—the specific word-for-word phrasing of something. For example, memorising every word of the story "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" would be remembering the syntax.

Semantic memory, however, is remembering the gist or meaning of the story—essentially, understanding that "Goldilocks enters the bears’ house, eats their food, sits in their chairs, and falls asleep in their bed." The exact words are not retained, but the main idea or meaning is.

Encoding information semantically in LTM means that our memory is not an exact replication of the actual event but rather an interpretation of it. Our intelligence, attention, biases, and personal understanding influence this interpretation. So, when we recall an event, we remember what it meant to us rather than every detail.

BADDELEY’S STUDY ON DIFFERENT TYPES OF ENCODING

Baddeley conducted a study examining the recall of acoustically and semantically similar and dissimilar words to test how STM and LTM encode differently.

Acoustically Similar and Dissimilar Words:

Acoustically Similar words sound similar (e.g., man, map, mat, mad).

Acoustically Dissimilar Words do not sound alike (e.g., pen, tree, sun, shoe).

In the experiment, when participants were asked to recall acoustically similar words immediately (using STM), they struggled more than dissimilar words, suggesting that STM relies heavily on acoustic encoding and that similar-sounding words can cause confusion.

Semantically Similar and Dissimilar Words:

Semantically Similar Words have similar meanings (e.g., big, large, huge, enormous).

Semantically Dissimilar Words have different meanings (e.g., small, red, tree, walk).

When participants were asked to recall semantically similar words after a delay (using LTM), they found it more difficult than recalling semantically dissimilar words. This indicates that LTM relies on semantic encoding and that words with similar meanings can be easily confused in LTM.

ASSESSMENT

SENSORY MEMORY

ONE MARK QUESTIONS

ODD ONE OUT

Iconic / Echoic / ProceduralODD ONE OUT

Taste / Smell / Balance

(Odd one out is not part of the standard sensory memory stores.)Which option is NOT a type of sensory memory?

A. Iconic

B. Procedural

C. Echoic

D. OlfactoryWhich of these describes the sensory register?

A. The long-term store for episodic memories

B. The initial store for raw, unprocessed sensory data

C. The part of memory used for problem solvingWhat happens to sensory information that is not attended to?

A. It is transferred to short-term memory

B. It decays almost immediately

C. It is processed for meaning

D. It is stored for later retrieval.Which store briefly holds visual information?

A. Echoic memory

B. Iconic memory

C. Haptic memory

D. Olfactory memoryWhich sensory memory lasts the longest?

A. Iconic

B. Echoic

C. Gustatory

D. HapticWhich statement best describes the relationship between sensory memory and consciousness?

A. Sensory memory operates outside conscious awareness

B. Sensory memory contains the information you are actively thinking about

C. Sensory memory is a form of deliberate storage

D. Sensory memory involves meaning-based processingSensory memory has which key feature?

A. Long duration, low detail

B. Short duration, high detail

C. Unlimited duration

D. Mainly verbal informationTRUE OR FALSE (

Sensory memory receives all sensory input, even if you are not paying attention.

Most information in sensory memory is lost unless attention selects it.

Sensory memory has unlimited duration.Which store briefly holds visual information?

A. Echoic memory

B. Iconic memory

C. Haptic memory

D. Olfactory memoryWhich sensory memory lasts the longest?

A. Iconic

B. Echoic

C. Gustatory

D. HapticWhich option is NOT a type of sensory memory?

A. Iconic

B. Procedural

C. Echoic

D. OlfactorySensory memory has which key feature?

A. Long duration, low detail

B. Short duration, high detail

C. Unlimited duration

D. Mainly verbal informationWhich store briefly holds visual information?

A. Echoic memory

B. Iconic memory

C. Haptic memory

D. Olfactory memoryWhich of these describes the sensory register?

A. The long-term store for episodic memories

B. The initial store for raw, unprocessed sensory data

C. The part of memory used for problem solvingWhich option is NOT a type of sensory memory?

A. Iconic

B. Procedural

C. Echoic

D. OlfactorySensory memory has which key feature?

A. Long duration, low detail

B. Short duration, high detail

C. Unlimited duration

D. Mainly verbal informationWhy don’t humans consciously perceive all sensory input? (3 marks).

Explain why sensory memory is described as high-resolution but brief (3 marks).

Outline sensory memory (3 marks).

SHORT-TERM MEMORY

TRUE OR FALSE

a. Information in sensory memory fades in 1–2 seconds, while short-term memories last several hours.

b. Short-term memories can be described, while sensory memories cannot.

c. The quality and detail of sensory memory are far superior to those of short-term memory.

d. Sensory memory stores auditory information, while short-term memory stores visual information.One key difference between sensory and short-term memory is that:

The most straightforward way to maintain information in short-term memory is to repeat the information in a process called:

a. Chunking

b. Rehearsal

c. Revision

d. RecallAn instructor gives her students a list of terms to memorise for their biology exam and immediately asks one student to recite them. Which terms will the student most likely recall?

a. The student won’t recall any terms because they have not used rehearsal to encode them.

b. Since there was no delay, the student will remember the terms at the end of the list.

c. Since there was no delay, the student will remember the terms at the beginning of the list.

d. The student will recall only those items to which they have attached some meaning.What is the function of short-term memory, and how does it differ from sensory memory?

What is the average capacity of short-term memory, and how much information can it hold?

Explain two ways information can be lost from short-term memory.

In your own words, describe how attention plays a role in transferring sensory memory into short-term memory.

How does rehearsal help maintain information in short-term memory? Provide an example.

Which of the following would be the easiest to chunk and therefore encode, and why?

a. 1982LOL

b. IEKFES

c. 278392

d. XYZZYXJamie wanted to contact his doctor. He looked up the number in his telephone directory. Before he dialled the number, he talked briefly with his friend. Jamie was about to phone his doctor, but had forgotten the number. Explain why Jamie forgot the number.

A mathematics teacher gives her students the following number to memorise for their geometry exam and immediately asks one student to recite it. The number is: 3.141592653589793. According to the primacy and recency effect, which numbers will the student most likely recall?

a. The student won’t recall any numbers because they have not used rehearsal to encode them.

b. Since there was no delay, the student will remember numbers at the end of the list.

c. Since there was no delay, the student will remember numbers at the beginning of the list.

d. The student will recall only those numbers to which they have attached some meaning.

e. The student will remember numbers at the beginning because they are now in long-term memory, and numbers at the end because they are still in short-term memory. The numbers in the middle would have been displaced

LONG-TERM MEMORY

12. What is the main difference between short-term and long-term memory?

13. Explain what happens to short-term memories that are not transferred to long-term memory.

14. In your own words, describe the role long-term memory plays in shaping who we are. Why is it considered the "record of the self"?

15. Why would the inability to transfer short-term memories to long-term memory result in conditions such as dementia?

What did George Miller (1956) discover about the capacity of Short-Term Memory? (2 marks)

Why is the capacity of LTM considered difficult to measure empirically? (2 marks)

What are the four primary research methods cognitive psychologists use to investigate mental processes and brain functioning? (4 marks)

What led to the rise of the Cognitive approach in psychology, and how did it differ from Behaviourism? (4 marks)

How did Atkinson and Shiffrin’s Multi-Store Model challenge earlier views of memory? (4 marks)

Explain how information is transferred from the Sensory Register to Short-Term Memory (STM). Provide an example. (4 marks)

What are the three key differences between STM and LTM in terms of encoding, based on Baddeley’s study? (6 marks)

What did Peterson and Peterson (1959) demonstrate about the duration of STM? (2 marks)

How did Bahrick et al. (1975) study the duration of Long-Term Memory (LTM), and what did they find? (4 marks)

What is semantic encoding, and how does it differ from remembering syntax? Give an example from a well-known story. (6 marks)

According to Baddeley’s study, how do acoustically similar and semantically similar words affect recall in STM and LTM? (6 marks)

How do laboratory experiments contribute to understanding cognitive processes, and what is an example of such an experiment? (2 marks)

What limitations of Behaviourism led to the development of the Cognitive approach? (4 marks)

How do Cognitive Science and the development of AI models help us understand human memory processes? (4 marks)

What were the main aims of Baddeley’s study, and what aspect of memory was he trying to investigate? (2 marks)

How did the procedure of Baddeley’s study differ when testing Short-Term Memory (STM) versus Long-Term Memory (LTM)? (2 marks)

According to Baddeley’s findings, what were the key differences in how STM and LTM encode information, and what conclusion did he draw from this? (2 marks)

What are the three distinct stores in Atkinson and Shiffrin’s Multi-Store Model of memory, and what role does each play? (6 marks)

FEATURES OF EACH MEMORY STORE: CODING, CAPACITY AND DURATION.

ENCODING QUESTIONS

1..Identify the primary type of coding used in each of the following components of the multi-store model of memory. 2 marks

Short-term memory

Long-term memory

2 Explain what is meant by encoding. 2 marks

Research has suggested that the encoding and capacity of short-term memory differ from encoding and capacity of long-term memory.

In an investigation into memory, participants were presented with two different lists of words

After seeing the lists, participants were tested on their ability to recall the words.

When tested immediately, participants found recalling the words from List A in the correct order more difficult.

When tested after 30 minutes, participants found recalling the words from List B in the correct order more difficult..

4. Using your knowledge of coding in memory, explain these findings. 4 Marks

5. Complete the missing parts of the table A, B, C and D about features of the multi-store memory model. 4 Marks

The following are all concepts relating to memory:

A Duration

B Capacity

C Encoding

D Retrieval.

6.In the table below, write which one of the concepts listed above (A, B, C or D) matches each definition. 2 marks

A researcher investigated coding in short-term memory using the same participants in both conditions.

In the first condition, he read out a list of 10 different sounding words.

In the second condition, he read out a list of 10 similar sounding words.

The researcher recorded how many words participants recalled correctly in each condition.

The table below shows the results of his study.

7. What do the mean values in the table suggest about coding in short-term memory? Justify your answer. 2 marks

PRACTICE QUIZ

1. The most straightforward way to maintain information in short-term memory is to repeat the information in a process called

a. chunking.

b. rehearsal.

c. Revisión.

d. recall. (1 mark)

2. Short-term memory is sometimes referred to as working memory because

a. To hold information in short-term memory, we must use it.

b. It takes effort to move information from sensory memory to short-term memory.

c. It is the only part of the memory system we must actively engage to retrieve previously learned information.

d. Creating short-term memories is a difficult task requiring a lot of practice. (1 mark)

3. An instructor gives her students a list of terms to memorise and immediately asks one student to recite them. Which terms will he most likely recall?

a. The end of the list (recency effect) and the middle of the list.

b. Beginning of the list (primacy effect) and the end of the list (recency effect).

c. Beginning of the list (primacy effect)

d. Only items with attached meaning (1 mark)

4. Which information is easiest to chunk?

a. 198274

b. KFCEEG

c. 278392

d. XYZZYX (2 marks)

5. Two key differences between sensory and short-term memory are that

a. The information in sensory memory fades in milliseconds, while short-term memories last for up to 30 seconds.

b. Short-term memories can be described, while sensory memories cannot.

c. The quality and detail of sensory memory are far superior to those of short-term memory.

d. Sensory memory stores auditory information, while short-term memory stores visual information. (2 marks)

6. Which situation best describes using hierarchies to memorise information?

a. Repeating each term

b. Organising notes into three themes

c. Writing definitions and reading them

d. Using flashcards (1 mark)

7. Memory researchers define forgetting as the

a. inability to retain information in working memory long enough to use it.

b. sudden loss of information after head trauma.

c. inability to retrieve information from long-term memory.

d. loss of information during transfer from short-term to long-term memory. (1 mark)

9. Which situation describes retroactive interference?

a. Samantha cannot recall her old postcode.

b. James keeps entering his old PIN.

c. Darnell travels to his old workplace on the train.

d. Fredrika calls her old boyfriend by her new boyfriend’s name (1 mark)

10. Naming as many state capitals as possible requires

a. cued recall

b. priming

c. spreading activation

d. free recall (1 mark)

11. Which pair is acoustically similar?

a. Man – Con

b. Nurse – Doctor

c. Weigh – Way

d. Apple – Radio (1 mark)

12. Priming is used when

a. He recalls only some items

b. He imagines a story linking all items

c. He is asked to name a dessert and says “cake”

d. He recalls only the first three (1 mark)

13. The inclusion of false details in memory is called the

a. priming effect

b. interference effect

c. tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon

d. misinformation effect (1 mark)

14. The method of loci involves

a. rhyming

b. acronyms

c. placing items in an imagined environment

d. pairing items with memorised cues (1 mark)

15. The tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon is

a. believing you experienced something when you have not

b. knowing something but unable to articulate it

c. hearing something you did not

d. knowing how to do something when you cannot (1 mark)

16. Patient H.M. suffered from

a. anterograde amnesia

b. confabulation

c. retrograde amnesia

d. Korsakoff’s syndrome (1 mark)

17. A tumour impairing new LTM formation most likely affects the

a. thalamus

b. hypothalamus

c. cerebellum

d. hippocampus (1 mark)

18. Declarative memory is _______ while task memory is _______.

a. declarative; non-declarative

b. non-declarative; episodic

c. episodic; semantic

d. non-declarative; declarative (1 mark)

19. Which situation uses episodic memory?

a. Giving a date of birth

b. Recalling your birthday party

c. Asking for a capital city

d. Recalling a historical fact (1 mark)

20. Semantic memories differ from episodic memories because they

a. are personal or emotional

b. contain no word meanings

c. lacks details about how information was learned

d. include procedural skills (1 mark)

21. Korsakoff’s syndrome involves cell loss in the

a. hippocampus

b. basal ganglia

c. mammillary bodies

d. pons (1 mark)

22. Non-declarative memory associations are learned via

a. conditioning

b. habituation

c. observational learning

d. procedural learning (1 mark)

23. The physical memory trace is called the

a. engram

b. hippocampus

c. hypothalamus

d. Hebbian synapse (1 mark)

24. A Hebbian synapse is strengthened when

a. The presynaptic neuron receives information

b. stimulation can be extinguished

c. the presynaptic neuron often makes the postsynaptic neuron fire

d. the postsynaptic neuron inhibits the presynaptic neuron (1 mark)

25. Long-term potentiation refers to long-lasting

a. memory deficits

b. mnemonic potential

c. synaptic inhibition

d. strengthening of synaptic transmission (1 mark)

26. Which pair is semantically similar?

a. mad – sad

b. hammer – sandwich

c. light – height

d. book – river

TYPES OF MEMORY: Sensory Register, Short-Term Memory and Long-Term Memory.

FEATURES OF EACH MEMORY STORE: Coding, Capacity and Duration.

TYPES OF LONG-TERM MEMORY: Episodic, Semantic, Procedural.

MODELS OF MEMORY:

The Working Memory Model – including The Central Executive, Phonological Loop, Visuo-Spatial Sketchpad and Episodic Buffer. Features of the model: coding and capacity.

MULTIPLE CHOICE (1 mark each)

The phonological loop mainly uses:

a. Acoustic coding

b. Visual coding

c. Semantic coding

d. Procedural codingThe articulatory control process performs:

a. Visual pattern storage

b. Subvocal rehearsal

c. Binding across modalities

d. Spatial rotationThe phonological store retains:

a. Visual detail

b. Raw speech sounds

c. Scent information

d. Long-term knowledgeThe visuospatial sketchpad processes:

a. Spoken words

b. Smell and taste

c. Visual and spatial information

d. Semantic categoriesThe visual cache is responsible for:

a. Colour and form

b. Inner speech

c. Task switching

d. Acoustic similarityThe inner scribe is responsible for:

a. Spatial layout and movement

b. Recognising familiar words

c. Visual colour recognition

d. Semantic processingSlave systems are “slave” because they:

a. Operate without attention

b. Are directed by the central executive

c. Store information permanently

d. Are part of long-term memoryThe episodic buffer allows the WMM to:

a. Maintain a visual store only

b. Rehearse speech

c. Integrate information from multiple modalities

d. Replace the phonological loopThe phonological loop’s capacity is:

a. Unlimited

b. Two seconds of sound

c. Seven visual chunks

d. Controlled by long-term memoryThe central executive is responsible for:

a. Storing verbal material

b. Controlling attention and switching tasks

c. Holding images indefinitely

d. Rehearsing soundsThe visuospatial sketchpad’s capacity is:

a. Unlimited

b. A small number of visual–spatial chunks

c. Determined by rehearsal speed

d. Equivalent to verbal spanThe episodic buffer differs from slave systems because it:

a. Stores only visual information

b. Integrates codes into coherent episodes

c. Has no capacity limit

d. Provides subvocal rehearsalArticulatory suppression disrupts performance because it:

a. Blocks the visual cache

b. Prevents the articulatory control process from refreshing material

c. Activates semantic memory

d. Overloads the central executiveThe phonological store is most disrupted by:

a. Bright colours

b. Spatial rotation

c. Similar sounding items

d. Semantic primingThe visuospatial sketchpad must be separate from the phonological loop because:

a. They handle incompatible coding systems

b. They share identical duration

c. Both store verbal material

d. They operate without the central executiveThe component that allocates attention and manages switching between tasks is the:

a. Phonological store

b. Visual cache

c. Central executive

d. Episodic bufferA person mentally rehearsing a phone number while imagining a route is using:

a. The visual cache for both tasks

b. The phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad separately

c. The episodic buffer only

d. The phonological loop onlyThe episodic buffer supports tasks such as mental reasoning because it:

a. Performs long-term retrieval

b. Merges verbal, visual and long-term information

c. Stores all information acoustically

d. Controls the allocation of attentionThe Working Memory Model is primarily:

a. A model of long-term memory

b. A model of short-term memory

c. A model of sensory memory

d. A model of autobiographical memoryIn Baddeley and Hitch’s original (1974) version, the Working Memory Model contained:

a. One STM store and one LTM store

b. The central executive, phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad

c. The central executive, episodic buffer and semantic system

d. Only a phonological loop and a visuospatial sketchpadWhich component was added approximately 25 years later to address integration and LTM interface problems?

a. Phonological loop

b. Visuospatial sketchpad

c. Episodic buffer

d. Sensory registerThe main reason Baddeley introduced the term “working memory” was to emphasise that STM is:

a. A permanent storage box

b. A passive container for 5–9 items

c. An active system involved in thinking and problem solving

d. Identical to long-term memoryCase studies such as KF suggested that STM:

a. Is a single, undivided system

b. Can transfer visual but not verbal information to LTM

c. Has unlimited capacity for verbal information

d. Is not involved in everyday cognitionWhich everyday situation best illustrates separate visual–spatial and verbal systems in STM?

a. Reading silently in a quiet room

b. Repeating a phone number to yourself

c. Navigating a busy street while talking on the phone

d. Sleeping after revisionThe phonological loop is specialised for:

a. Storing shapes and colours

b. Storing autobiographical events

c. Processing and rehearsing verbal and auditory information

d. Storing semantic knowledge from LTMThe visuospatial sketchpad is specialised for:

a. Storing smells and tastes

b. Visual and spatial information such as layouts and locations

c. Episodic memories from childhood

d. Rehearsing speech-based materialThe visuospatial sketchpad’s capacity is approximately:

a. 20 objects

b. 3–4 objects or chunks of visual–spatial information

c. 7 plus or minus 2 items

d. Unlimited if colour is simpleThe phonological loop primarily encodes information:

a. Visually

b. Semantically

c. Acoustically (by sound)

d. ProcedurallyThe visuospatial sketchpad primarily encodes information:

a. By meaning alone

b. In visual and spatial formats (appearance and location)

c. As inner speech

d. As emotionally charged episodesThe phonological store (“inner ear”) is best described as:

a. An active rehearsal mechanism

b. A passive store holding sounds for 1–2 seconds

c. A long term store for speech

d. A visual pattern recogniserThe articulatory control process (“inner voice”) is best described as:

a. A buffer for multimodal information

b. An automatic store for semantic knowledge

c. A system that refreshes sounds by silent repetition

d. A system that encodes colour and shapeThe central executive mainly:

a. Stores detailed visual and verbal information

b. Controls attention and allocates resources between systems

c. Stores personal episodes from the past

d. Converts STM into LTMThe episodic buffer was introduced because the original model:

a. Had no verbal store

b. Could not explain how information from different systems was bound into a single episode

c. Overestimated STM capacity

d. Already explained the link to LTM in detailThe episodic buffer is described as:

a. A processor of sound only

b. A processor of images only

c. A limited capacity store that binds verbal, visual and LTM information into coherent episodes

d. A permanent store for autobiographical memories.

SHORT QUESTIONS

State what the Working Memory Model is a model of. 1 mark

State the original three components of the Working Memory Model proposed by Baddeley and Hitch. 1 mark

Name the fourth component later added to the model and state roughly when it was introduced. 2 marks

Explain why case studies such as KF suggest that short-term memory is not a single, unitary store. 2 marks

Explain why Baddeley and Hitch preferred the term “working memory” instead of “short-term memory”. 2 marks

Outline what is meant by a “slave system” in the Working Memory Model. 2 marks

Close your eyes and picture your home. Now count the number of windows it has. Don’t say anything out loud — do it silently in your head.

How did you work out the number of windows? 1 mark

What does this show about how your memory handles visual and spatial information? 1 mark

Explain why the phonological loop cannot maintain verbal material for long without rehearsal. 2 marks

Describe how the visuospatial sketchpad supports tasks such as imagining layouts or navigating a route. 2 marks

Explain why the central executive is capacity-limited. 2 marks

Describe how the episodic buffer links working memory with long-term memory. 2 marks

Explain why the Working Memory Model requires separate systems for verbal and visuospatial information. 2 marks

Describe the two components of the phonological loop and explain how they work together. 3 marks

Describe the roles of the phonological store and articulatory control process within the phonological loop. 3 marks

Describe the roles of the visual cache and inner scribe within the visuospatial sketchpad. 3 marks

Explain the difference between the visual cache and inner scribe and give an example of each. 3 marks

Explain how the episodic buffer integrates verbal, visuospatial and long-term memory inputs. 3 marks

Explain how the episodic buffer allows working memory to combine verbal, visual and long-term information. 3 marks

Explain how capacity and duration are described for the phonological loop, including how speech rate affects them. 3 marks

Explain the capacity and duration of the visuospatial sketchpad, and how task complexity influences what can be held. 3 marks

Describe how differences in coding between the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad support the claim that working memory has multiple specialised subsystems. 3 marks

Explain why the central executive is essential for coordinating complex behaviour, using one example. 3 marks

Describe what is meant by a “slave system” and explain why the model includes more than one. 4 marks

Explain the coding and capacity differences between the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad. 4 marks

Describe two limitations of the central executive and how these affect complex cognitive tasks. 4 marks

Explain the interactive roles of the phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad, central executive and episodic buffer in a task such as reading or mental arithmetic. 4 marks

APPLIED QUESTIONS QUESTIONS FOR THE WORKING MEMORY MODEL INCLUDE:

SCENARIO-BASED QUESTION

Read the four scenarios below. Each one involves attempting two tasks simultaneously.

A. Solving a complex algebra equation while learning a new dance routine.

B. Reciting a poem from memory while cycling.

C. Driving down a narrow mountain road while debating climate change.

D. Swimming the butterfly stroke while counting backwards in twos.

Answer the following questions:

For each scenario, is it realistically possible to carry out both tasks simultaneously without one impairing the other? Explain briefly. (2 marks)

For each scenario, identify which task relies mainly on phonological processing and which relies primarily on visuospatial processing. (2 marks)

For each scenario, classify the dual-task combination as:

• Both tasks are easy

• Both tasks are difficult

• One task is complex, and one is easierDescribe four strengths of the working memory model. (8 marks)

Describe the weaknesses of the working memory model (4).

Identify and explain one weakness of the working memory model (4 marks).

Identify and explain one strength of the working memory model (4 marks).

Outline the working memory model (6 marks).

·Outline and evaluate The Working Model of Memory (16 Marks).

·Discuss The Working Model (16 Marks).

FULL A01 MARK QUESTIONS

Describe how the central executive manages the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad when a person is driving on a challenging road while talking to a passenger. 4 marks.

Please explain how the episodic buffer solves the integration problem in the original Working Memory Model and how it links working memory with long-term memory. 4 marks

Discuss the role of the articulatory control process in maintaining and manipulating verbal information in the phonological loop. 4 marks

Explain how the visuospatial sketchpad contributes to reasoning tasks that require mental rotation or spatial comparison. 4 marks

Describe how the episodic buffer resolves the limitations of the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad when information needs to be integrated into coherent episodes. 4 marks

Explain how the Working Memory Model accounts for the simultaneous manipulation and storage of different types of information. 5 marks

Using an example such as watching a film or baking a cake from a video recipe, explain how all four components of the Working Memory Model (central executive, phonological loop, visuospatial sketchpad and episodic buffer) operate together. 5 marks

Discuss how the articulatory process, phonological store, visual cache, inner scribe and episodic buffer support complex reasoning, comprehension and spatial planning. 5 marks

Analyse how each component of the Working Memory Model contributes to the active processing required for planning, problem-solving or decision-making. 5 marks

Explain, with reference to coding, capacity and function, why the Working Memory Model requires multiple controlled subsystems rather than one general-purpose short-term store. 5 marks

Evaluate the Working Memory Model with reference to coding, capacity and function in each subsystem, showing how these demonstrate a fractionated temporary memory system. 6 marks.

Describe, in detail, how all components of the WMM function together during tasks involving language, imagery, navigation and decision making. 6 marks

“Short-term memory is not a passive box for 5–9 items; it is an active, multi-component system involved in thinking.” Using the Working Memory Model, explain this statement with reference to coding, capacity and the functions of at least two slave systems and the central executive. 6 marks

Evaluate the Working Memory Model as an explanation of short-term memory, referring to evidence from neuropsychological case studies, the introduction of the episodic buffer, and the existence of separate capacity-limited slave systems. 6 marks

Describe how the Working Memory Model accounts for real-world cognition by explaining the distinct contribution of each subsystem to tasks such as comprehension, navigation, mental imagery and verbal retention. 6 mark.

MARK SCHEME: WORKING MEMORY MODEL A01

·Identification of components of the model and a brief outline of their function:

Likely Features are the three main components: the central executive, which coordinates the other two slave systems and is involved in attention and higher mental processes. It has a limited capacity and can process information in any mode.

The phonological loop is involved in holding speech-based information and articulatory control processes of inner speech.

The visuospatial scratchpad processes visual-spatial information and is involved in pattern recognition and the perception of movement.

Four statements/descriptions of different components of the working memory model:

Stores acoustically coded items for a short period.

Stores and deals with what items look like and their physical relationship.

Encodes data in terms of its meaning.

It acts as a form of attention and controls slave systems.

Components of the working memory model: phonological store, visuospatial sketch pad, articulatory process, and central executive.

SIX-MARK ANSWER: THE WORKING MEMORY MODEL

The Working Memory Model (WMM) was proposed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974) to address limitations in the Multi-Store Model’s (MSM) description of Short-Term Memory (STM) as a passive and unitary store. The WMM describes STM as an active system with multiple components that temporarily store and manipulate information.

The model includes the Central Executive, which acts as a "boss" by allocating attention and resources to two slave systems: the Phonological Loop and the Visuospatial Sketchpad. The Phonological Loop processes verbal and auditory information and has two components: the Phonological Store, which holds sound-based information, and the Articulatory Process, which rehearses verbal information. The Visuospatial Sketchpad processes visual and spatial data and comprises the Visual Cache, which stores visual details, and the Inner Scribe, which handles spatial information and movement.

In 2000, Baddeley added the Episodic Buffer to address criticisms of the original model. The Episodic Buffer integrates information from the slave systems and Long-Term Memory (LTM), creating unified episodes and supporting tasks like problem-solving and narrative comprehension.

The WMM provides a more detailed and dynamic explanation of STM than the MSM, highlighting how different types of information are processed simultaneously.

This version meets the requirements for a six-mark A-Level question by explaining the WMM’s components, addressing the addition of the Episodic Buffer, and contrasting it with the MSM for evaluation.

EVALUATION QUESTIONS

STUDENT ACTIVITY: RUN YOUR OWN DUAL-TASK EXPERIMENT

Instructions

Choose two tasks:

Pick one verbal task and one visual–spatial task.

Examples:

• Verbal: remember a short list of words, rehearse a phone number, spell words backwards

• Visual–spatial: track a moving shape on screen, draw a simple pattern from memory, count how many squares are shaded in a gridDo each task on its own first:

Complete the verbal task by itself and record how well you perform.

Then complete the visual–spatial task by itself and record your performance.Now perform both tasks at the same time:

Try to do the verbal task while doing the visual–spatial task.

Record how performance changes (speed/accuracy / how difficult it felt).Swap your tasks with a partner:

Let them choose their own verbal and visual–spatial tasks.

Compare your results.

Questions for students to answer

Was your performance worse when you did two tasks at once?

Did the verbal task interfere with the visual–spatial one, or could you do both fairly well?

What does this suggest about how the phonological loop and visuospatial sketchpad work?

Extension (optional)

Repeat the experiment but use two verbal tasks at the same time (e.g., remembering digits while spelling words backwards).

Compare the difficulty with doing one verbal and one visual–spatial tas

ANSWERS

A complex algebra problem and learning a new dance simultaneously? It's unlikely. Both tasks demand significant attention, meaning the Central Executive must decide which task to focus on to avoid failing both.

Reciting a poem from memory while cycling? This might be manageable, as both tasks might not require excessive additional attention, allowing the Central Executive to distribute resources evenly.

Driving on a perilous mountain path while debating vigorously about climate change? Again, probably not. The complexity of both tasks means the Central Executive would have to prioritise, likely focusing more on driving to ensure safety.

Could a professional footballer execute a tackle while counting backwards in twos? In this case, the tasks could be managed with uneven attention. The physical task might not hamper the simple mental task of counting, suggesting the Central Executive can allocate resources differently based on task demands.

EXPLANATIONS FOR FORGETTING: Proactive and Retroactive Interference and Retrieval Failure due to the absence of cues.

FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY: Misleading Information, including Leading Questions and Post-Event Discussion

FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY: Anxiety.

IMPROVING THE ACCURACY OF EYEWITNESS TESTIMONY: The Cognitive Interview

MODELS OF MEMORY: THE MULTI-STORE MODEL OF MEMORY

POSSIBLE EXAM QUESTIONS FOR THE MULTI-STORE MEMORY MODEL INCLUDE:

Patient X: difficulty forming new long-term memories after a car accident, but intact short-term memory and intact memories from before the accident. Briefly explain how the experiences of Patient X could be interpreted as supporting the multi-store memory model. (2 marks)

What do you understand by the following terms:

(a) short-term memory

(b) long-term memory?

List three differences between STM and LTM.

According to Miller, how does ‘chunking’ increase the capacity of STM?

Identify two factors that affect the duration of STM.

Outline the procedures and findings of the Peterson and Peterson study of duration in STM.

What is the preferred method of encoding in

(a) STM

(b) LTM?

Outline the findings of the study by Bahrick et al. (1975) into very long-term memory. Identify one criticism of this study.

Outline the main features of the working memory model.

Outline findings of research investigating the levels-of-processing model.

To what extent does the multi-store model explain how memory works?

The multi-store model of memory has been criticised in many ways. The following example illustrates a possible criticism.

“Some students read their revision notes many times before an examination, but still find it challenging to remember the information. However, the same students can remember information from a celebrity magazine even though they read it only once.”

Explain why this can be used as a criticism of the multi-store model of memory. (3 marks)

Outline what psychological research has shown about short-term memory according to the multi-store memory model. (4 marks)

A researcher investigating the multi-store memory model tested short-term memory by having participants read aloud sequences of numbers, which they had to repeat immediately after presentation. The first sequence consisted of three numbers, for example, 8, 5, 2. Each participant was tested several times, and each time the sequence length was increased by adding another number.

Use your knowledge of the multi-store memory model to explain the purpose of this research and the likely outcome. (4 marks)

After the study was completed, the researcher decided to modify the test by using letter sequences rather than numbers. Suggest one 4-letter sequence and one 5-letter sequence that the researcher could use. For each sequence, give a different rationale. (4 marks)

Evaluate the use of case studies, such as that of Patient X, in psychological research. (5 marks)

Patient X: severe amnesia after accident, cannot form new long-term memories, short-term memory intact.Outline the multi-store model of memory. (6 marks)

Outline and evaluate the multi-store memory model. (8 marks)

Evaluate the multi-store memory model. (10 marks)

Outline and evaluate the multi-store memory model. (16 marks A-level

MEMORY RESOURCES

MEMORY TEST:https://memtrax.com/test/

FURTHER READING:

“The Universe Within” by Morton Hunt (Simon & Schuster, 1982)

“The 3-Pound Universe” by Judith Hooper and Dick Teresi (Dell Publishing Co, 1986)

“The Britannica Guide to the Brain” by Cordelia Fine (Robinson, 2008)

“Your Brain: The Missing Manual” by Matthew MacDonald (Pogue Press/O’Reilly, 2008)

https://writemypaperhub.com is a professional research paper writing website for ordering a unique academic project on human memory topics.

MEMORY WEBSITES:

(Wikipedia): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memory (plus other links from there)

https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/memory/

How Human Memory Works (HowStuffWorks): http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/life/human-biology/human-memory.htm

How Amnesia Works (HowStuffWorks): http://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/life/human-biology/amnesia.htm

Memory (Sceptic’s Dictionary): http://www.skepdic.com/memory.html

The Brain From Top To Bottom (McGill University): http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/

How Does Your Memory Work (BBC TV): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxVb6M8UPTQ

Memory–Structures and Functions (State University): http://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2222/Memory-STRUCTURES-FUNCTIONS.html

FILMS:

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), Michel Gondry

Three Colors: Blue (1993), Krzysztof Kieślowski

Memento (2000), Christopher Nolan

FIFTY-FIRST DATES

The Father [2021]

Still Alice (2014)

Away From Her (2007)

The Savages (2007)

The Notebook (2004)

A Song for Martin (2001)

Age Old Friends (1989)

Firefly Dreams (2001)

Iris: A Memoir of Iris Murdoch (2001