RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORIES AND SCHEMAS

Memories are not just records of the past — they are the architecture of the self. They tell us who we are, where we've been, and who we think we’ve become. But these inner archives are far from flawless. Rather than fixed snapshots of truth, memories are fragile reconstructions — fluid, selective, and easily manipulated. We treat them as anchors to our identity, yet they shift subtly with every recollection, shaped by perception, emotion, and time. In trusting them, we risk mistaking stories for facts, and echoes for evidence.

WHAT IS RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY?

Have you ever recalled a vivid memory, only to discover it wasn’t quite how you remembered?

You might be sure you remember the scene perfectly — the weather, what you were wearing, who was there, even what someone said. Maybe you’ve told the story a few times: how you got lost in a crowd, how someone unexpected turned up, how a moment unfolded in an unforgettable way.

But then, years later, someone gently corrects you. They say someone couldn’t have been there — they were away that week. Or it wasn’t winter, it was summer. Or you were much younger than you thought. Suddenly, the memory that felt so solid starts to blur at the edges.

How can something feel so real… and still be wrong?

This is reconstructive memory at work. Our brains don’t store events like perfect video recordings. Instead, memories are actively pieced together during recall, blending accurate details with assumptions, expectations, and prior knowledge. In this case, because Christmas fairs often feature Santa Claus, your brain may have “filled in the blanks,” adding him to your memory even though he wasn’t there. It’s not a flaw—it’s your mind working hard to make sense of the event.

This process helps us organise and interpret experiences, but also means our memories aren’t always reliable. We may add details that didn’t happen or forget ones that did. Reconstructive memory highlights how we blend the real and the imagined, revealing how flexible and fallible our recall can be..

But before we can fully explore how and why memories become reconstructed, we need to understand the cognitive building blocks that underpin them: schemas. These mental frameworks shape how we organise, store, and retrieve information. They are essential for long-term memory and play a crucial role in helping us interpret the world around us.

As we’ll see, schemas are not just passive filing systems—they actively filter experiences, influence perception, and quietly shape how we remember. And that’s where things start to get interesting.

SCHEMAS ARE THE BRAIN'S BEST FRIEND

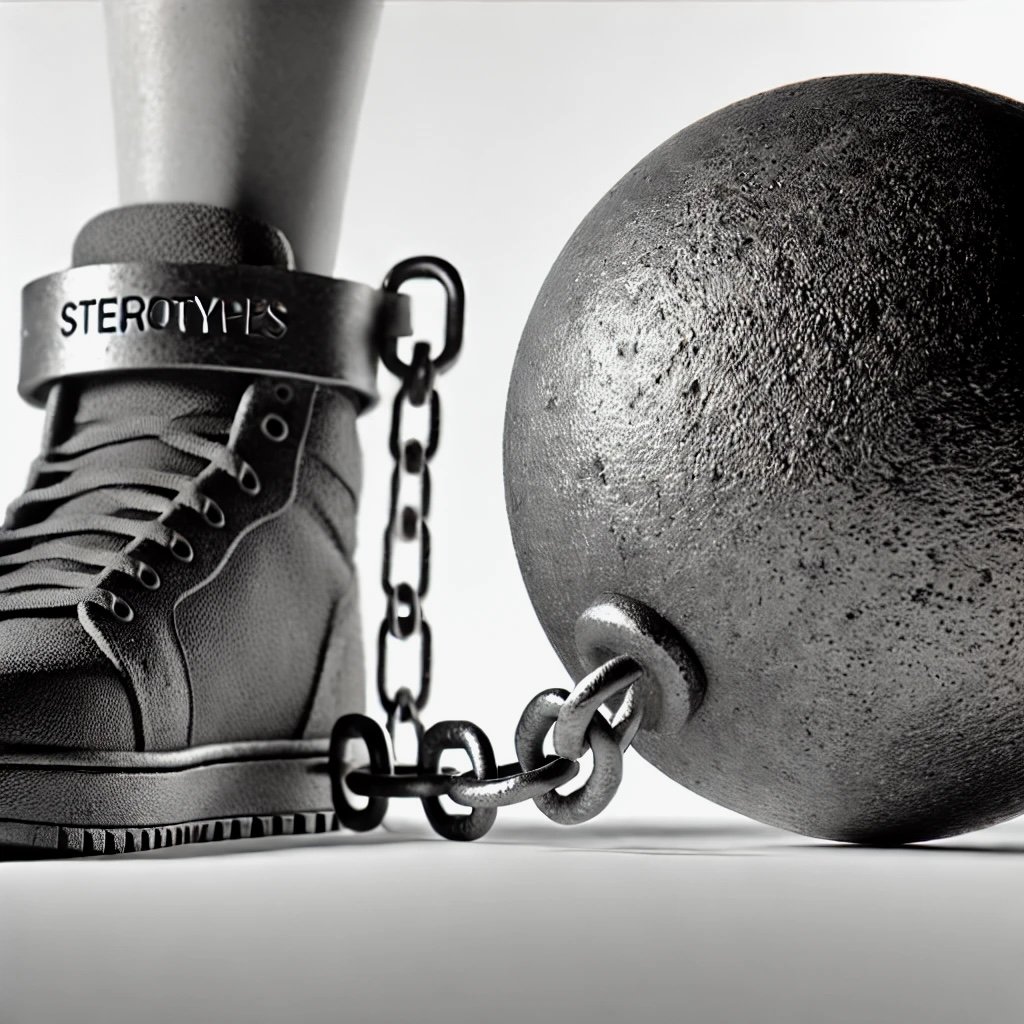

Knowledge is physically expressed in the brain, and stereotypes are one way this knowledge is organised. A stereotype is a sub-category of schemata—or, more commonly, schema. Schemas act as a mental database, categorising everything we encounter into broad groups: for instance, "baby" equals can’t talk, can’t walk, cries, and dribbles. Stereotypes, as specific schemas, allow us to judge people or situations quickly. For example, the stereotype “all old people are frail” helps us decide to offer an elderly lady a seat on the bus without overthinking her physical capabilities. Without stereotypes, we’d waste time assessing every individual—babies, the elderly, or harmless strangers—for potential danger. Stereotypes are mental shortcuts, saving us cognitive effort.

ACTIVITY INSTRUCTIONS:

EXPLORING STEREOTYPES AND ASSUMPTIONS

OBJECTIVE

This activity helps you uncover and reflect on the assumptions we make about people based on their names and countries of origin.

INSTRUCTIONS

Step 1: ASSUMPTIONS (10 minutes)

Below are six individuals from different regions. For each person, write five things you assume about them. Consider their:Appearance (e.g., hair, skin tone, clothing).

Personality traits.

Daily lifestyle or routines.

Hobbies or interests.

Cultural or traditional practices.

THE PEOPLE

Inga is from Sweden.

John is from the USA.

Aarav is from India.

Tariq is from the Cook Islands.

Zenaw is from Kazachnya (a region combining cultural influences from Kazakhstan and Chechnya).

Nokani is from a remote Amazon jungle tribe.

STEP 2: SELF-REFLECTION (10 minutes)

After writing your assumptions, consider the following:IDENTIFY PATTERNS

What do your assumptions reveal about how you view these cultures?

Were your responses influenced by stereotypes or media portrayals?

CHALLENGE YOURSELF

Could these assumptions be incorrect or overly simplistic?

What additional information would you need to understand these individuals and their cultures better?

Whatever your answers were, don’t feel too bad, stereotypes are essential. If you don’t have a stereotype of a person, they can’t exist in your brain. For instance, if someone asked you what kind of person a Kolpat is? You'd have no idea what colour their hair is, what shade their skin is, and what their customs are, etc., because Kolpats don’t exist; I just made them up. Still, your brain likely searched for matches to categorise them. But how can you imagine a person with zero data to go on? Most of our decisions rely on stereotypes. So, if I told you Kolpats were from Western Europe, you might now guess they had dark hair and tanned skin based on your prior experience in other words, some stereotypes would kick in. Similarly, if I told you my elderly parent’s friend from Jamaica was visiting. You’d probably picture an elderly Black person who enjoys reggae based on your cultural knowledge and personal history. But what if this friend turned out to be a 21-year-old, Chinese-looking goth? This mismatch would surprise you because your brain had pre-existing stereotypes.

No harm done—hopefully, you’d update that stereotype accordingly.

EXERCISE 1: PAYING ATTENTION TO YOUR ENVIRONMENT

Tune in to your surroundings by focusing on your senses, one at a time. What can you hear? What can you feel against your skin? What subtle details do you notice that you hadn’t before?

As your attention sharpens, you might pick up on background sounds or sensations that had gone entirely unnoticed — a ticking clock, distant traffic, or the texture of your clothing.

This shift in awareness highlights something remarkable about how your brain works. Until now, those sensations weren’t on your radar because they weren’t necessary. The brain filters and prioritises — it simply can’t process every detail flooding in at every moment. So it chooses what matters, and quiets the rest. This is because vast volumes of sensory information continually bombard the brain during every moment of a human's life. However, our sensory memory can only process a fraction of this sensory information because they have limited capacity.

ATTENTIONAL PROCESSES

This ability to selectively focus enables you to tune into a conversation in a noisy café, recognise a familiar face in a crowd, or instinctively brake when a fox darts across the road. Despite the constant flood of sensory data, your brain efficiently filters the noise to prioritise what matters most in the moment.

Attention functions like a spotlight, casting clarity on significant events while the rest fades into the background. It's a powerful tool that helps us navigate the world, not by processing everything, but by zeroing in on what’s relevant. In doing so, perception becomes our way of engaging with the present, helping us construct a meaningful and manageable version of reality.

THE £5 NOTE CHALLENGE: WHY YOUR BRAIN FAILS AT DETAILS

I want to set you a quick challenge to prove how your brain filters out what it doesn’t think is essential, even if you see it daily.

Take five minutes and try to draw a five-pound note (or whatever currency you use) entirely from memory. Don’t cheat. No peeking. You’ve handled money since childhood — yet most people fail at this task. Why?

Because your brain zones out “noise.” It registers only the essentials: the colour, general layout, maybe a face or number. What are the intricate patterns, specific wording, or exact placement of features? Discarded.

This simple exercise shows how your brain cuts corners to conserve mental energy. You don’t need the full detail to recognise a banknote, so your brain builds a shortcut. It’s efficient, but we've never noticed much of what we “see” daily.

The brain's prioritisation system is designed to prevent overload. It doesn’t waste energy, deeply encoding every aspect of every object you encounter. Instead, it filters out what it deems non-essential, ensuring that attention is reserved for more pressing matters. This is why shortcuts like schemata and stereotypes are so important—they allow us to navigate our environment without becoming paralysed by detail.

This failure to recall the details of something as familiar as money isn’t about memory but efficiency. Your brain doesn’t waste energy storing high-resolution images of things it doesn’t need to recall. Instead, it filters for usefulness and fills in the rest with mental shortcuts.

THE BRAIN AS A COGNITIVE MISER

The brain speculates rapidly to save energy. When you’ve figured out whether a “slippery-looking” character following you in the park is harmless or dangerous, it might be too late — you could be mugged. On the other hand, you might feel guilty for stereotyping them when they turn out to be a park keeper doing litter duty.

We all “jump the gun” at times. Ideally, these blunders help update our mental shortcuts. Staying “street-wise” is essential, but clinging to outdated stereotypes — like imagining all French people wear strings of onions — is irrational.

This reminds me of Martin Vagner’s quote from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo:

“Why don’t people trust their instincts? They sense something is wrong, and someone is walking too close behind them. You knew something was wrong, but you came back into the house. Did I force you, did I drag you in? No. All I had to do was offer you a drink. It’s hard to believe that the fear of offending can be stronger than the fear of pain.”

This quote highlights how instincts — often shaped by schemas and stereotypes — aim to protect us. Yet, stereotypes have gained a bad reputation due to their association with prejudice, leading many to suppress or mistrust them. In truth, they are mental shortcuts — tools our brain uses to navigate uncertainty — and only become harmful when left unexamined or used inflexibly.

SCHEMATA AND STEREOTYPES

Our brains need to organise the flood of sensory information into manageable patterns to avoid overload. To do this, we rely on schemata, biases, and stereotypes — mental shortcuts that help us quickly sense the world.

In psychology, a schema is a structured cluster of knowledge — a cognitive framework that allows us to interpret and respond to new information based on what we already know. These mental templates help us navigate life efficiently, grouping information into categories and defining relationships between them.

Like your sketchy memory of a £5 note, most of our experiences are recorded in shorthand. We store the gist, not the detail. This cognitive economy helps us act fast and lays the foundation for stereotyping. When encountering unfamiliar people or situations, the brain fills in the gaps with generalised assumptions. These may be based on limited exposure, cultural messages, or past experiences.

In short, stereotypes aren’t just social flaws — they’re symptoms of a brain trying to be efficient.

HOW SCHEMATA DEVELOP

Imagine an infant encountering the world for the first time. They wouldn’t know where one object begins and another ends, nor would they know names, smells, or functions. Infants interact with the world by seeing, touching, and mouthing objects. Over time, they form basic schemata—categories based on their experiences. For example, their understanding of soft textures or the structure of their language is influenced by culture, parenting, and media.

The first six months of brain development are critical as infants wire neural connections to everything they encounter. They seek patterns and associations to make sense of their surroundings. As they grow, their schemata evolve and become more refined.

Two key cognitive processes—assimilation and accommodation—are central to the development and function of schemata. These mechanisms help us make sense of new information by fitting it into what we already know or adjusting our existing frameworks when the latest data doesn’t quite fit.

ACCOMMODATION AND ASSIMILATION

Let’s say Mary is a toddler with a golden retriever named Frank. She visits her uncle, who owns a Dachshund. Mary identifies the Dachshund as a dog, even though it looks different from Frank. This is called assimilation—adding new information to an existing schema.

Later, Mary visits her grandma, who owns a rabbit. She calls the rabbit a “dog” because her schema for dogs is too broad; it only contains four legs and fur, for example. When her mother corrected her, Mary adjusted her schema and included her tail, size, and ears in her schemata for rabbits and dogs. This process, called accommodation, refines her understanding by creating a new category for “rabbit.

CULTURAL SCHEMAS AND MEMORY

Schemas don’t form in isolation. They are shaped and reinforced by culture, family, media, and the social environments we grow up in. These mental frameworks help us organise incoming information, predict outcomes, and decide how to respond to situations. Over time, they become the scaffolding through which we filter and understand the world.

For instance, cultural storytelling norms strongly influence how we interpret and remember narratives. In Western societies, stories are expected to follow a particular arc: beginning, middle, climax, and resolution. This shapes a cultural schema that values clarity, closure, and linear logic.

The film Leave the World Behind offers a good example. Its ambiguous, open-ended conclusion left many Western viewers feeling confused or unsatisfied. Their memory of the film may focus less on the plot and more on its "lack of ending." But that frustration comes not from the movie but the schema being violated. Viewers anticipated resolution; when it didn’t arrive, their recollection became skewed by that unmet expectation.

By contrast, other cultures favour circular or morally symbolic stories without a clear resolution. In these contexts, ambiguity is not only accepted but expected. As a result, memory reconstruction may centre on symbolism or moral meaning rather than "what happened." This contrast shows how cultural schemas influence what we pay attention to, what we expect, and ultimately what we remember.

EXPECTATIONS: THE ARCHITECTS OF MEMORY

Expectations lie at the heart of every schema. They guide how we process the present and reconstruct the past. Instead of storing perfect recordings, the brain builds memories by piecing together fragments of real experience with imagined or inferred details, many of which are supplied by what we expect to happen.

Take the example of a child whose schema tells them that dogs are friendly. If they initially meet a dog and feel fear, but the interaction turns out positive, they may reconstruct the memory as entirely pleasant, editing out their hesitation. Their expectation—that dogs are friendly—overwrites the detail.

This becomes especially important in eyewitness testimony, where expectation can lead to severe distortions. A witness might assume that a robbery involves a man in a mask, so even if the criminal’s face was visible, their memory might fill in a mask later. Similarly, suppose they’re told the robber had a weapon or wore gloves. In that case, they might incorporate these false details into their account, especially if they align with existing schemas about how crimes "should" look.

FROM SCHEMAS TO RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY

Schemas and the expectations they create are not just tools for everyday thinking—they shape what we remember, how we remember, and how we misremember. They help us interpret our world efficiently and make our memory vulnerable to distortion. As we’ll see in the next section, memory is not a passive storage system—it’s a dynamic, reconstructive process, one that’s guided as much by what we anticipate as by what we experience. For example, imagine visiting a zoo and later trying to recall the details of the day. Your schema for "zoo visits" might include expectations like seeing various animals, hearing children's excitement, and eating snacks. If you don't clearly remember what you ate, your schema might lead you to fill in this gap with typical zoo food, such as popcorn or ice cream, even if you had something different. This example shows how schemas guide memory recall, helping to reconstruct the day's events by filling in gaps with plausible details based on past experiences and general knowledge of what happens at the zoo.

SIR FREDERIC BARTLETT: THE FATHER OF SCHEMA THEORY

Sir Frederic Bartlett’s groundbreaking research aimed to answer a fundamental question: how do we store and recall information that doesn’t make sense to us? Bartlett’s experiments on memory reconstruction revealed that when faced with ambiguous or meaningless stimuli, the brain relies on existing knowledge and mental frameworks, or schemas, to encode and retrieve information.

One of Bartlett’s most famous experiments involved ambiguous drawings, such as two small circles joined by a line or abstract tribal artefacts. These images were deliberately meaningless—objects for which participants would have no prior schema. The goal was to understand what happens when you try to store and recall something you don’t recognise. How can you encode something when you don’t have a framework to interpret it? It’s like trying to remember a conversation in a language you don’t understand—if the words have no meaning, you can’t recall them because there’s no structure (semantics or gist) to anchor them in memory.

Bartlett found that participants couldn’t reproduce the ambiguous drawings accurately. Instead, they transformed them, interpreting the shapes as recognisable and familiar. For example, two circles joined by a line might be remembered as “glasses” or “dumbbells.” A crescent shape might become a “moon” or “canoe.” This wasn’t a random process—it was the participants’ way of giving the ambiguous stimuli meaning so they could store and recall it. Without a schema to categorise the original drawing, the memory would otherwise have no way to take root.

This experiment demonstrated that memory is not a perfect replica of the past. Instead, it’s a reconstructive process where the brain relies on schemas to interpret and store information. When something doesn’t fit an existing schema, we reshape it to align with what we already know. Bartlett’s work revealed that we don’t store memories word for word (syntax) but by their meaning or the “gist” (semantics). This explains why we can remember general conversations but struggle to recall meaningless strings of words or details we don’t understand.

BARTLETT'S AMBIGUOUS FIGURES (1921)

Can you trust your memory? Let’s find out.

Instructions:

You’ll see a set of simple, abstract shapes below.

📌 You have 1 minute to study them.

Don’t take notes.

Just observe as carefully as you can.

Once the time is up, look away and try to draw them from memory.

When you're finished, compare your version to the original.

❓ WHAT DID YOU NOTICE?

Did you distort the shapes without realising it?

Did you reinterpret them into familiar objects (e.g. glasses, dumbbells, a canoe)?

Were there parts you added, simplified, or replaced?

This process is a perfect example of schema-driven memory reconstruction:

🧠 When faced with ambiguity, the brain fills in the blanks using pre-existing mental frameworks. It doesn’t just store what you saw — it reshapes it to make it meaningful

Bartlett's research on interpreting ambiguous drawings illustrates that when individuals encounter a vague image, they instinctively relate it to familiar schemata.

.

THE WAR OF THE GHOSTS

"The next study that Bartlett (1932) conducted focused on the impact of existing knowledge frameworks on memory recall, aiming to demonstrate how prior knowledge — or schematic knowledge — shapes and influences memory reconstruction

AIMS AND IMPLICATIONS

Bartlett aimed to show how schemas influence memory by forcing participants to engage with a story outside their cultural context

Bartlett carefully chose The War of the Ghosts, a Native American folk tale, for his experiment because it radically differed from the types of stories his English participants were familiar with. Unlike Western narratives, which often follow a linear structure with transparent cause-and-effect relationships, The War of the Ghosts contains fragmented, illogical, or culturally specific elements in the Native American context.

The story’s features posed unique challenges to Bartlett’s participants:

CULTURAL DISSONANCE

The story includes unfamiliar cultural references, such as the supernatural nature of the "ghosts" and the use of canoes. For English participants, these elements lacked the context to make sense of them. Unlike Western stories, which typically feature relatable characters and situations, this tale assumed cultural knowledge that the participants did not have.NON-LINEARITY AND AMBIGUITY

Western stories often follow a clear, linear progression with a beginning, middle, and end. In contrast, the War of the Ghosts includes abrupt shifts, such as the sudden revelation that the warriors are ghosts and the unexplained death of the protagonist. These features made the story feel disjointed and difficult to rationalise within the participants' schemas.LACK OF MORAL OR RESOLUTION

Western stories frequently conclude with a moral or resolution that ties the narrative together. In The War of the Ghosts, the protagonist’s death and the mysterious "black thing" leaving his mouth provided no closure, leaving participants uncertain about the story’s meaning or purpose.

THE STORY

“"One night two young men from Egulac went down to the river to hunt seals, and while they were there it became foggy and calm. Then they heard war-cries, and they thought: "Maybe this is a war-party". They escaped to the shore, and hid behind a log. Now canoes came up, and they heard the noise of paddles, and saw one canoe coming up to them. There were five men in the canoe, and they said: "What do you think ? We wish to take you along. We are going up the river to make war on the people". One of the young men said: "I have no arrows". "Arrows are in the canoe", they said. "I will not go along. I might be killed. My relatives do not know where I have gone. But you", he said, turning to the other, "may go with them." So one of the young men went, but the other returned home. And the warriors went up the river to a town on the other side of Kalama. The people came down to the water, and they began to fight, and many were killed. But presently the young man heard one of the warriors say: "Quick, let us go home: that Indian has been hit". Now he thought: "Oh, they are ghosts". He did not feel sick, but they said he had been shot. So the canoes returned to Egulac, and the young man went ashore to his house, and made a fire. And he told everybody and said: " Behold, I accompanied the ghosts, and we went to fight. Many of our fellows were killed, and many of those who attacked us were killed. They said I was hit, and I did not feel sick". He told it all, and then he became quiet. When the sun rose he fell. Something black came out of his mouth. His face became contorted. The people jumped up and cried. He was dead.“ (p.65)

FINDINGS

Because the story did not align with the participants' schemas—mental frameworks shaped by their cultural knowledge—they struggled to process and recall it accurately. This mismatch forced participants to reconstruct the story in a way that made sense to them, often leading to significant distortions. They replaced unfamiliar details with more culturally familiar ones, like changing “canoe” to “boat” or interpreting the warriors as soldiers. Supernatural elements were downplayed or omitted entirely, as they clashed with Western rationalist perspectives.

This highlights a fundamental aspect of human cognition: people judge and interpret new information through the lens of what they already know. When faced with something unfamiliar, they instinctively try to fit it into their existing frameworks, even if that distorts the original meaning. Bartlett’s choice of this culturally distinct story was deliberate—it exposed how deeply cultural biases shape our memory and understanding.

WHAT THIS REVEALS ABOUT THINKING AND JUDGMENT

Bartlett’s experiment with The War of the Ghosts provides groundbreaking insights into the way we think and remember, fundamentally altering our understanding of memory as a reconstructive process:

COHERENCE AND THE NEED FOR MEANING

Faced with ambiguity, the human mind craves coherence. Bartlett’s participants instinctively restructured the story, eliminating details they couldn’t rationalise and imposing a logical flow in line with Western storytelling conventions. This need for meaning drives us to impose order on the unfamiliar, but it comes at a cost—accuracy. The supernatural, fragmented nature of The War of the Ghosts conflicted with participants’ expectations of narrative structure, forcing them to alter it to make sense of it.

BIAS AND THE LIMITATIONS OF JUDGMENT

Bartlett’s study exposed the biases inherent in human cognition. Participants unconsciously reshaped the story to fit their worldview rather than engaging with the story on its terms. This highlights the limitations of human judgment—how we instinctively evaluate unfamiliar ideas against our cultural expectations, often simplifying or distorting the original. Bartlett’s findings are a stark reminder of how difficult it is to approach new information without bias.

ROLE OF SCHEMAS IN MEMORY

Bartlett’s research laid bare the essential role of schemas in shaping how we interpret, encode, and recall information. Schemas are not just passive knowledge repositories but active frameworks that organise and interpret the world around us. However, they also create blind spots: memory struggles to take hold when no schema exists for unfamiliar or ambiguous stimuli.

COGNITIVE IMPLICATIONS

Bartlett’s work shattered the illusion of memory as a faithful recorder of past events, revealing instead that memory is:

ACTIVE AND CONSTRUCTIVE

Memory is not about retrieving a perfect record but reconstructing a coherent narrative. This reconstruction is guided by pre-existing knowledge and schemas, which aid comprehension and introduce distortion. Bartlett’s participants, for example, restructured the story into a more familiar, Western-style narrative to make it easier to recall.DEPENDENT ON MEANING

Information must have meaning for memory to function effectively. Bartlett’s study revealed that when faced with unfamiliar or ambiguous details, the mind struggles to encode them. Participants omitted or altered such details, highlighting the limitations of memory when it cannot link new information to existing schemas.

A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF MEMORY

Bartlett’s work fundamentally redefined memory, shifting the focus from static recall to dynamic reconstruction. Memory is not an objective playback of the past—it is an interpretative process deeply influenced by personal and cultural contexts. This groundbreaking insight challenged existing theories of memory. It paved the way for modern cognitive psychology, revealing the intricate balance between the utility of schemas and the distortions they inevitably introduce. Bartlett’s findings remain as revolutionary today as they were in the 1930s, providing a lens to understand how we remember, perceive, judge, and make sense of the world.

BRANSFORD AND JOHNSON: CONTEXT AND COMPREHENSION

Bartlett’s work showed that memory is reconstructive, shaped by prior knowledge and schemas. But what happens when we encounter something new, and we don’t have an existing schema? How do we make sense of it? How does new, ambiguous, contextless information get processed? How do we memorise something completely unfamiliar? Where does it go in memory if there’s no framework to attach it to?

Let’s try a quick example.

Take a look at this excerpt: Read it carefully, and try to figure out what the narrator is doing:

GUESS THE TASK

“The procedure is actually quite simple. First you arrange things into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities, that is the next step; otherwise, you are pretty well set. It is important not to overdo things. That is, it is better to do too few things at once than too many. In the short run, this may not seem important, but complications can easily arise. A mistake can be expensive as well. At first, the whole procedure will seem complicated. Soon, however, it will become just another facet of life. It is difficult to foresee any end to the necessity for this task in the immediate future, but then one never can tell. After the procedure is completed, one arranges the materials into different groups again. Then they can be put into their appropriate places. Eventually, they will be used once more, and the whole cycle will then have to be repeated. However, that is part of life.”

What do you think this procedure is describing?

Take a guess — don’t scroll yet. Need a clue?

Clue 1: It’s something ordinary that most people do about once or twice a week, depending on their lifestyle or the size of their family.

Clue 2: It involves sorting, repetitive steps, and organisation.

SPOILER ALERT: THE ANSWER

The passage describes doing the laundry.

Bransford and Johnson (1972) presented this passage to participants under three conditions: one group was told the title before reading, one received no context, and one was told the title after reading.

The results were precise: Those given the context beforehand understood and remembered the passage much better than the other groups. The words felt vague and disconnected without the schema (“doing the laundry”). With the schema in place, participants could make sense of the details and store them meaningfully.

In a similar study, Bransford and Johnson presented participants with the following passage:

“If the balloons popped, the sound wouldn't be able to carry since everything would be too far away from the correct floor. A closed window would also prevent the sound from carrying since most buildings tend to be well-insulated. Since the whole operation depends on a steady flow of electricity, a break in the middle of the wire would also cause problems. Of course, the fellow could shout, but the human voice is not loud enough to carry that far. An additional problem is that a string could break on the instrument. Then, there could be no accompaniment to the message. The best situation would involve less distance. Then there would be fewer potential problems. With face-to-face contact, the least number of things could go wrong. “(p. 719)

Participants were divided into groups. One group was given the picture below, while another received the passage without a picture. A third group was given the picture only after reading the passage.”

The participants who viewed the picture before reading the paragraph found the text more comprehensible, and their memory retention was notably better. However, when the same picture was presented after reading the paragraph or when only a partial view of the image was provided before reading, participants struggled to make sense of the paragraph, leading to reduced memory recall.

In this experimental context, the picture serves as a schema, providing a structure to the information in the paragraph and guiding the selection of what is remembered. Without this guiding structure, participants lacked a framework to identify what data to place, resulting in limited memory retention. Notably, the effectiveness of the picture as a schema was most pronounced when presented before participants read the paragraph, highlighting the crucial role of schemas during the encoding phase—the process of storing new information.

BRANSFORD AND JOHNSON: MAKING SENSE OF MEMORY

Bransford and Johnson’s research expanded on Bartlett’s ideas about memory reconstruction but shifted the focus to the immediate context at the time of encoding. While Bartlett demonstrated how cultural schemas and personal experiences shape memory over time, Bransford and Johnson highlighted how the initial framing of information determines how well it is understood and remembered. They showed that the brain struggles to assign meaning to ambiguous or unclear information, resulting in poor or zero encoding. But when relevant context is provided—whether a title, an explanation, or a mental framework—individuals can better select, file, and encode meaningful details, making the information more accessible.

Their findings revealed that context acts like a mental scaffold, allowing the brain to organise and store information more effectively.

THE SELECTION PRINCIPLE

Bransford and Johnson introduced the selection principle, which explains how individuals focus on the most relevant or meaningful aspects of information when encoding and recalling it. This principle emphasises that memory is not an all-or-nothing process; instead, we filter and prioritise details based on their perceived significance.

For example, imagine reading an instruction manual for assembling furniture. Without a diagram or clear context, the steps might feel overwhelming and disjointed. But with a clear visual or a brief introduction about the goal—“assembling a bookshelf”—you are more likely to focus on the relevant details and ignore extraneous information. This filtering process is the selection principle in action, showing how context helps us make sense of and remember complex information.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

Bransford and Johnson’s work wasn’t just about memory and how we make sense of the world. Their research demonstrated that comprehension and recall are not passive but active, deeply reliant on meaningful context. Without context, information is chaotic and forgettable. With it, the brain can organise and encode information, turning the abstract into the familiar and the confusing into the comprehensible.

Like Bartlett’s, Bransford and Johnson's findings fundamentally challenged the idea of memory as a straightforward storage and retrieval system. Instead, they revealed memory as a dynamic and interpretative process, shaped not only by what we already know but also by the clarity and framing of new information. Bransford and Johnson’s work remains a cornerstone of cognitive psychology, showing us that understanding begins with context.

OTHER FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY

EXPECTATIONS AND BELIEFS

Our beliefs and expectations filter how we interpret and recall events. If you assume a close friend always supports you, you might later remember them agreeing with your ideas, even if they voiced doubts. Your brain reconstructs the event to align with your expectations, shaping your memory to fit what feels consistent with your worldview.

POST-EVENT DISCUSSION

The post-event discussion refers to the information encountered after an initial event, which can become interwoven with the original memory. This phenomenon demonstrates the malleability of human memory, showing how subsequent experiences can reshape or distort recollections.

For example, after witnessing a crime, an individual might engage in discussions with others, read media reports, or participate in interviews. These interactions can introduce new information that merges with their memories, leading them to recall events differently. This “memory contamination” often results in a blend of actual observations and post-event details, significantly affecting the accuracy of recollections.

The implications of post-event information are particularly critical in legal contexts. For example, an eyewitness who encounters misleading post-event details might recall events inaccurately, potentially misidentifying suspects or recalling events that never occurred. This underscores the importance of controlling for post-event influences to ensure the reliability of testimony.

LEADING QUESTIONS

The phrasing of questions during memory retrieval is another crucial factor in memory distortion. Leading questions—suggesting a specific answer or introducing new information—can significantly alter an individual’s recollection of an event.

For instance, asking, “Was the car red when you saw the accident?” assumes the car's presence and its colour, potentially leading a witness to “remember” a red car even if they never noticed or recalled one. Such suggestions become integrated into the memory, distorting its accuracy.

The impact of leading questions in legal settings is profound. Poorly worded questions in police interviews, courtroom testimonies, or depositions can introduce inaccuracies that lead to false confessions, wrongful convictions, or flawed witness identifications. Crafting neutral and non-suggestive questions is vital to preserving the integrity of eyewitness memories.

EMOTIONAL STATE AT THE TIME OF MEMORY

Emotions exert a significant influence on how memories are encoded and reconstructed. Strong emotions during an event, such as fear during a robbery or joy at a wedding, can shape what details are emphasised and which are forgotten.

For example, fear during a traumatic event might heighten focus on a threatening element, like the assailant’s weapon, while obscuring contextual details such as the environment. Conversely, happiness at a celebration might enhance positive recollections, embellishing the memory and making it seem more idyllic than it was.

This interplay between emotion and memory highlights the complexity of recollection. While emotions can enhance vividness, they can also introduce biases, leading to selective or distorted recall.

CONFIRMATION BIAS

Confirmation bias further complicates reconstructive memory. Individuals with strong beliefs or feelings about an event tend to remember details that align with these views while ignoring or misremembering conflicting information. For instance, a person who believes someone acted suspiciously might recall behaviours that confirm this belief, even if those actions were innocuous.

RUMINATION

Repeatedly revisiting or ruminating on an event can also alter how it is remembered. Over time, rumination can amplify or diminish specific aspects of a memory. For example, dwelling on an embarrassing incident might make the memory feel more humiliating than it originally was. Similarly, revisiting a happy event might enhance its positive aspects while downplaying harmful elements.

APPLYING SCHEMAS AND RECONSTRUCTIVE MEMORY TO LONG-TERM MEMORY

By this stage, we’ve seen how schemas shape understanding and how memories are reconstructed rather than replayed. What matters now is how these two concepts — schema and reconstructive memory — work together within long-term memory (LTM).

Long-term memory doesn’t store a perfect copy of our experiences. Instead, it encodes meaning (semantics), not exact wording or order (syntax). When we recall events, the mind reconstructs them based on gist, context, and prior knowledge, not precise detail.

Hearing a story like Goldilocks and the Three Bears. You likely remember that Goldilocks entered a house, tried three bowls of porridge, sat in three chairs, and slept in three beds — each one being either too much or “just right.” But if asked to retell the story word-for-word, most people can’t. They remember the structure, the pattern, and the moral, not the precise phrasing. This shows how long-term memory stores the essence of an experience, not its exact details.

SCHEMAS AND RECONSTRUCTION: HOW THEY INTERACT IN LTM

Schemas help us make sense of new information during encoding — they provide the scaffolding. Later, they’re also used to fill in any gaps during recall. This makes memory efficient, but it also creates room for distortion.

Schema-based assumptions: If someone hears about a dinner party but wasn’t told what food was served, their schema for parties might automatically assume there was a main course and dessert.

Distortions: If real events don’t match a schema, we may unconsciously reshape the memory to fit—for example, assuming a masked robber when there wasn’t one or, as shown in The War of the Ghosts, replacing unfamiliar cultural features with ones that align with our own expectations.

WHY THIS MATTERS TO LONG-TERM MEMORY RESEARCH

Understanding the relationship between schemas and reconstruction is essential for studying long-term memory, because it explains not just what we remember, but why we misremember:

Eyewitness testimony: People often fill in or misinterpret details of crimes to match their schemas of what a robbery “should” look like.

Education: Teachers can support memory by anchoring new material to students’ existing schemata, improving encoding and retrieval.

Therapy: Helping clients reframe traumatic memories shows how schemas and reconstruction can evolve, shaping healthier narratives.

IN SUMMARY

Schemas act as mental frameworks for encoding meaning, and reconstructive memory is the process by which those meanings are retrieved, filled in, filtered, and rebuilt. Long-term memory is not passive or exact; it is interpretative, flexible, and schema-driven.

Our brains prioritise understanding, coherence, and efficiency, not accuracy. As a result, long-term memory is rich in meaning but prone to error. This intersection between schema and reconstruction offers a powerful lens to understand how we record, recall, and reinterpret our past.