CULTURAL BIAS

SPECIFICATION: Culture bias in Psychology: Cultural bias includes ethnocentrism and cultural relativism

IS PSYCHOLOGY CULTURALLY BIASED?

Modern psychology presents itself as a science of universal human behaviour. Yet much of its theoretical foundation has been developed within a narrow cultural context. Historically, the discipline has been dominated by Western, primarily American institutions, and many classic studies have relied heavily on American undergraduate samples. Rosenzweig (1992) estimated that approximately 64% of the world’s psychologists were American at the time. Textbook analyses reinforce this imbalance: Baron and Byrne’s (1991) social psychology text cited 94% of studies from North America. More recent reviews of leading journals such as Psychological Science continue to show that between 80–95% of participants are drawn from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) populations, despite these groups representing only around 12% of the global population.

The issue is not simply demographic imbalance but epistemological limitation. When psychological theories are constructed using culturally specific participants, the assumptions embedded within their social world become normalised and rendered invisible. Concepts such as independence, self-esteem, romantic love, intelligence, attachment, morality, and mental illness may be defined through Western individualistic frameworks and then presented as universal features of human psychology.

This creates a structural risk: psychology may conflate what is culturally typical with what is biologically fundamental. If findings derived from Western individualistic populations are generalised globally, cultural variation can be misinterpreted as deviation. Behaviours that diverge from Western norms may be classified as irrational, maladaptive, or deficient when they may instead reflect alternative social logics.

Cross-cultural research illustrates these differences clearly. In Japan, the meaning of “work” often extends beyond formal labour to include after-hours socialising with colleagues (nomikai), reflecting a collectivist emphasis on relational obligation and group harmony rather than a strict separation between professional and personal life. Research on emotion perception has shown that East Asian participants tend to focus more on the eyes when interpreting facial expressions, whereas Western participants rely more heavily on the mouth. Classic studies on emotional display rules found that Japanese participants masked negative emotions in social contexts to preserve harmony, while American participants were more likely to express them openly. Moral judgement research similarly indicates that collectivist cultures may place greater emphasis on norm conformity and social obligation, whereas individualistic cultures prioritise personal autonomy and rights.

At the same time, cross-cultural comparisons must avoid equating nation with culture. A single country often contains multiple subcultures, and national-level comparisons do not automatically capture cultural variation. Nevertheless, the overwhelming concentration of psychological research within WEIRD contexts remains a significant limitation.

Cultural bias is therefore structural rather than incidental. It shapes the questions psychologists ask, the behaviours they operationalise, the measures they construct, and the interpretations they produce. Without systematic cross-cultural validation, psychology risks presenting one culturally specific worldview as a universal account of human nature.

SO WHAT IS CULTURE?

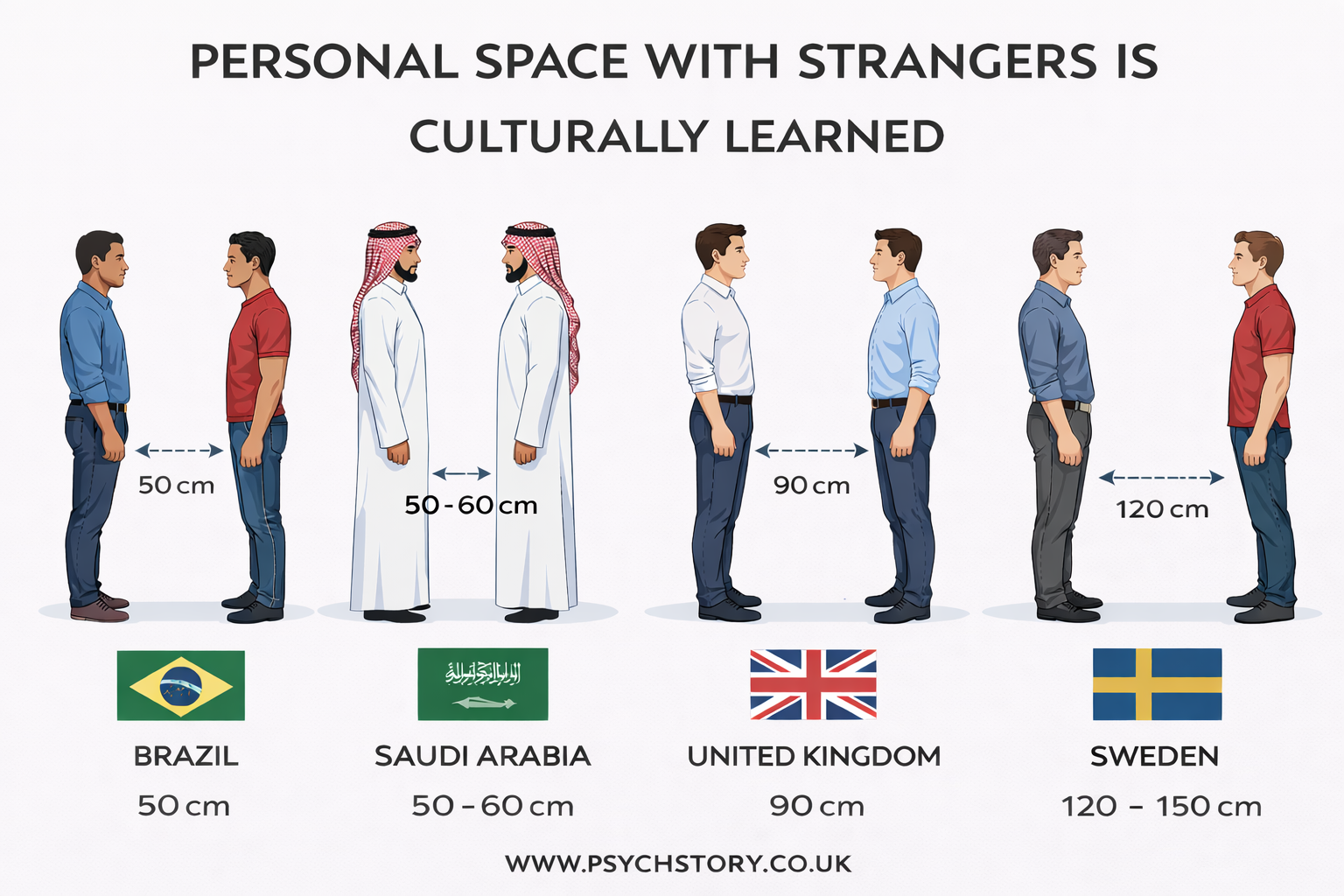

Culture is the shared system of meanings, expectations and rules that a group of people use to organise social life. It shapes how individuals interpret reality, define what is normal, decide what is right or wrong, and understand their roles within a community. Culture is not limited to nationality or ethnicity. It includes patterns of thinking, behaving and valuing that are transmitted across generations through family, education, religion, media and social institutions. It provides the psychological framework through which experience is interpreted.

Several core components make up culture:

VALUES

Values are deeply held beliefs about what is important, desirable or worth striving for. They guide priorities and life decisions. For example, independence and personal achievement are highly valued in many Western societies, whereas loyalty to family and respect for elders are prioritised in many collectivist cultures. Values influence choices about marriage, career, education and moral judgment.NORMS

Norms are the unwritten social rules about how people are expected to behave in everyday situations. They regulate conduct and maintain social order. For example, queuing in Britain is a social norm. Speaking loudly in public may be acceptable in one culture and inappropriate in another. Norms define what attracts approval and what attracts social disapproval.MORES

Mores are strong moral norms that carry greater emotional and ethical significance. They reflect a culture’s core moral standards. Violating a more is not simply unusual; it is regarded as morally wrong. For example, expectations around sexual behaviour, modesty, religious observance or family duty often function as mores. Breaking them can lead to serious social condemnation.BELIEFS

Beliefs are shared assumptions about how the world works. These may include religious beliefs, beliefs about mental illness, beliefs about gender roles, or beliefs about authority. For example, some cultures interpret mental distress through spiritual frameworks, whereas others interpret it through medical or psychological explanations.PRACTICES AND TRADITIONS

Practices are the behavioural expressions of cultural values and norms. These include marriage customs, mourning rituals, parenting styles, educational expectations and dietary rules. Traditions are practices transmitted across generations that reinforce group identity.LANGUAGE

Language structures communication and influences thought. It shapes how emotions are labelled and understood. Some languages contain words for relational or emotional states that do not exist in English, which affects how experience is conceptualised.SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Culture also includes expectations about hierarchy, status and power. Some societies are more egalitarian, while others emphasise authority, age, gender or class distinctions. These structural differences influence autonomy, obedience and identity formation.

WHY THIS MATTERS FOR PSYCHOLOGY

Psychology frequently attempts to define what is normal, rational or disordered behaviour. However, such definitions are filtered through cultural values, norms and mores. Behaviour that violates norms in one culture may be typical in another. Without recognising cultural context, psychological theories risk treating culturally specific behaviour as universal human nature

CULTURES WITHIN CULTURES: SUBCULTURES

Within any dominant culture, there are multiple subcultures. A subculture is a group within a larger society that maintains distinct values, norms, identities or lived experiences, while still existing inside the broader cultural framework. Subcultures may be shaped by ethnicity, region, social class, religion, age, gender, disability, occupation or sexual orientation. They may overlap with the dominant culture in many respects, but they also maintain important psychological and social differences.

For example, within England there are numerous subcultures: Afro-Caribbean communities, Polish communities, Jewish communities, Deaf communities, LGBTQ+ communities, regional identities such as Northerners, as well as groups differentiated by wealth, education or social class. Each of these groups may share aspects of wider British culture, yet differ significantly in values, expectations, communication styles, family structures or attitudes towards authority and mental health.

This distinction is critically important in psychological research. Cultural bias is often discussed as a cross-national problem, but it is equally a within-society problem. Research conducted in a single city, university or social class is frequently presented as representative of an entire nation.

This becomes particularly problematic in cross-cultural research involving countries labelled as “individualistic” or “collectivist”. Nations such as India, Russia or South Africa contain vast internal diversity. If research is conducted in a highly urban, educated, economically developed setting such as Mumbai and then used to represent “India”, the findings may reflect a modern, globalised, middle-class subculture rather than rural or traditional communities. In fact, similarities between urban professionals in Mumbai and those in London or New York may be greater than those between Mumbai and rural villages in India.

The same applies to countries undergoing rapid economic change. As economies develop, urban areas often become more individualistic, while rural areas retain collectivist values. Treating a nation as culturally uniform oversimplifies reality and risks generating misleading conclusions.

For psychology, this has major implications. If studies draw primarily from a single dominant subgroup within a country, conclusions may not generalise to other subgroups within that society. Cultural bias, therefore, operates at two levels:

• Across countries

• Within countries

Understanding subculture prevents psychology from confusing a particular social group with a universal human standard

TEMPORAL VALIDITY AS A FORM OF CULTURAL BIAS

Temporal validity can be understood as a form of cultural bias extended across time rather than across geography. Culture is not only spatial. It is historical. Each era functions almost like a subculture with its own norms, values, technologies, moral assumptions and dominant explanatory frameworks.

Temporal validity refers to whether findings remain accurate as time passes. Cultural bias refers to whether findings are overgeneralised beyond the cultural context in which they were produced. When the culture changes across decades or centuries, the issue becomes temporal cultural bias.

The “culture” of Victorian England is not the same as the culture of 2025 Britain. The culture of 1950s America is not the culture of post internet global society. Each period has:

• Different gender norms

• Different family structures

• Different economic conditions

• Different educational access

• Different moral codes

• Different technologies

• Different dominant scientific paradigms

If research findings are treated as universal despite being rooted in one historical context, that is effectively a failure of temporal validity and a form of cultural bias.

For example:

Freud’s psychosexual theory reflects Victorian repression and patriarchal norms.

Milgram’s obedience findings reflect post war authority structures.

Asch’s conformity levels decline in later replications because individualism increased over time.

Gender role research from the 1950s cannot be assumed to apply to Generation Z.

Zeitgeist captures this idea. The spirit of the age shapes what questions are asked, what is considered deviant, what is morally acceptable, and what behaviours are typical.

In that sense, temporal validity is historical cultural bias. The past is a different culture. Treating it as equivalent to the present is methodologically naïve

CULTURAL MODELS OF SELFHOOD

INDIVIDUALISTIC CULTURES

Individualistic cultures prioritise the self over the group. Decisions about marriage, career, lifestyle and identity are typically based on personal preference, self fulfilment and individual gain. Independence from parents is encouraged, and adulthood is associated with leaving the family home and achieving financial and social autonomy.

However, individualism does not emerge in a vacuum. It is closely linked to economic stability and state infrastructure. Individualistic cultures tend to develop in economically secure, high-GDP nations in which the state provides a robust welfare system. This may include pensions, unemployment benefits, maternity pay, child allowance, subsidised or free healthcare, education grants and reliable transport systems. Because individuals are “buffered” by the state, survival does not depend entirely on extended family support.

In such contexts, people do not need to marry to secure economic survival or family alliances. Women need not remain in marriages to avoid destitution. Career choices can be made on the basis of interest rather than family necessity. Elderly relatives can be supported through pensions rather than relying solely on children. Childcare may be state-subsidised rather than provided exclusively by extended kin.

In relationships, marriage is often based on attraction, compatibility and personal fulfilment. Divorce rates are higher, and serial monogamy is common. Gender equality tends to be more pronounced. Spouses are usually chosen independently and often have no prior family connection.

Geographically, individualistic cultures are more common in parts of Northern Europe, North America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. These regions generally have higher economic development and stronger welfare infrastructures.

Importantly, individualism is not fixed. It shifts with economic conditions. For example, younger generations in economically pressured societies may remain living at home longer due to high housing costs, student debt and unstable employment. In such cases, even historically individualistic societies may display more collectivist features out of economic necessity. Cultural orientation, therefore, fluctuates alongside economic security.

In this sense, individualistic cultures can afford to prioritise the self because survival is not entirely dependent on the family. Where the state assumes responsibility for welfare, healthcare and education, the family becomes less economically central.

COLLECTIVIST CULTURES

Collectivist cultures prioritise the group, particularly the family or community, over the individual. Decisions about marriage, employment, and social roles are often guided by considerations of what benefits the wider group rather than personal desire.

Collectivism is frequently associated with societies where state infrastructure is weaker. In contexts where welfare provision is limited, there is no universal healthcare, pensions are minimal, access to higher education is restricted, and employment protection is limited, individuals rely heavily on family networks for survival. The family functions as the primary economic and social safety net.

Marriage may therefore be arranged or strongly influenced by elders because it consolidates family alliances and resources. Spouses are often selected from similar religious, social or economic backgrounds to maintain stability. Divorce may carry severe economic consequences, particularly for women in contexts where employment opportunities and welfare support are limited.

Sexual behaviour may also be more tightly regulated in collectivist societies, particularly where contraception or abortion access is restricted. The economic and social costs of an unplanned pregnancy are higher when state support is minimal.

Collectivist cultures are more common in parts of Africa, South Asia, East Asia excluding Japan, and Central and South America. However, these categories are broad and contain enormous internal diversity. Urban areas within collectivist nations may display more individualistic traits than rural regions.

As economies develop, collectivist cultures may gradually shift towards individualism. China and India, for example, exhibit increasing individualistic tendencies in economically prosperous urban regions. Culture, therefore, evolves alongside economic and structural change rather than being permanently fixed.

MASCULINE AND FEMININE CULTURES

Hofstede also distinguished between masculine and feminine cultures.

Masculine cultures emphasise achievement, competition, status and independence. Success, ambition and performance are highly valued. Japan and the United States score highly on masculinity indices. In highly competitive systems without universal welfare provision, economic security may strongly influence mate selection and social decision-making.

Feminine cultures emphasise care, cooperation, quality of life and social support. Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands are often cited as examples. These societies tend to provide stronger welfare systems, greater gender equality and more extensive social protections.

WHY THIS MATTERS FOR PSYCHOLOGY

These cultural dimensions are not simply descriptive labels. They influence attitudes towards family, gender roles, mental health, independence, conformity and morality. If psychological theories are developed in highly individualistic, economically secure contexts, they may assume personal choice, autonomy and mobility as universal norms. These assumptions may not hold in collectivist or economically constrained environments.

Culture is therefore inseparable from economic structure, social policy and historical development. Understanding individualism and collectivism requires examining how societies are organised materially, not simply ideologically.

REFERENCES

Hofstede, G. (1987). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1(2), 81–99.

Moghaddam, F. M. (1993). Individualism and collectivism: Social psychological perspectives and applications. In U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, Ç. Kağıtçıbaşı, S. C. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 19–40). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

BIASED WAYS OF VIEWING CULTURE IN PSYCHOLOGY

Cultural frameworks rarely present themselves as local. They are typically experienced as natural. Difficulties arise when one cultural framework becomes the standard against which all others are evaluated. In psychology, this evaluative bias can transform difference into deficiency.

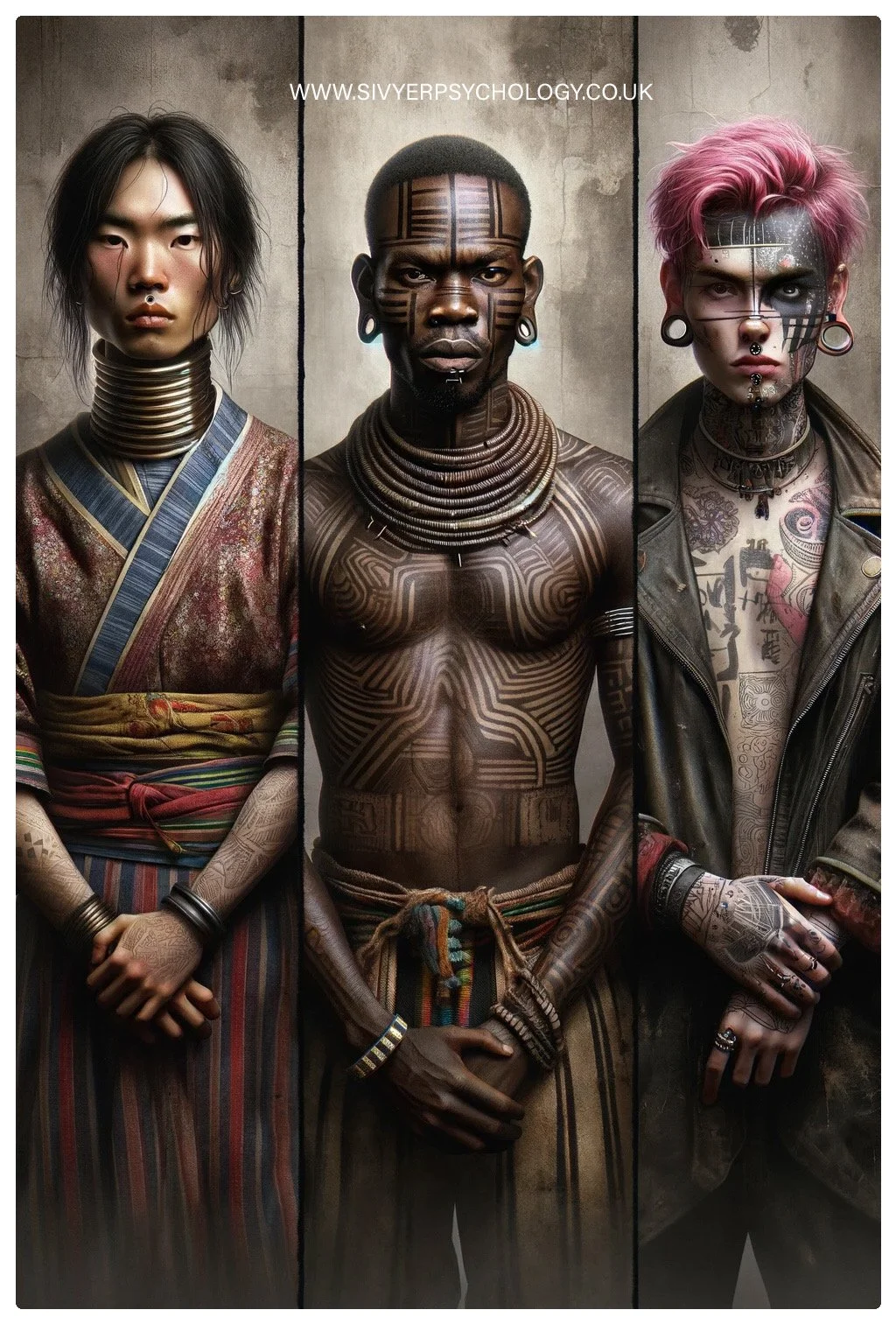

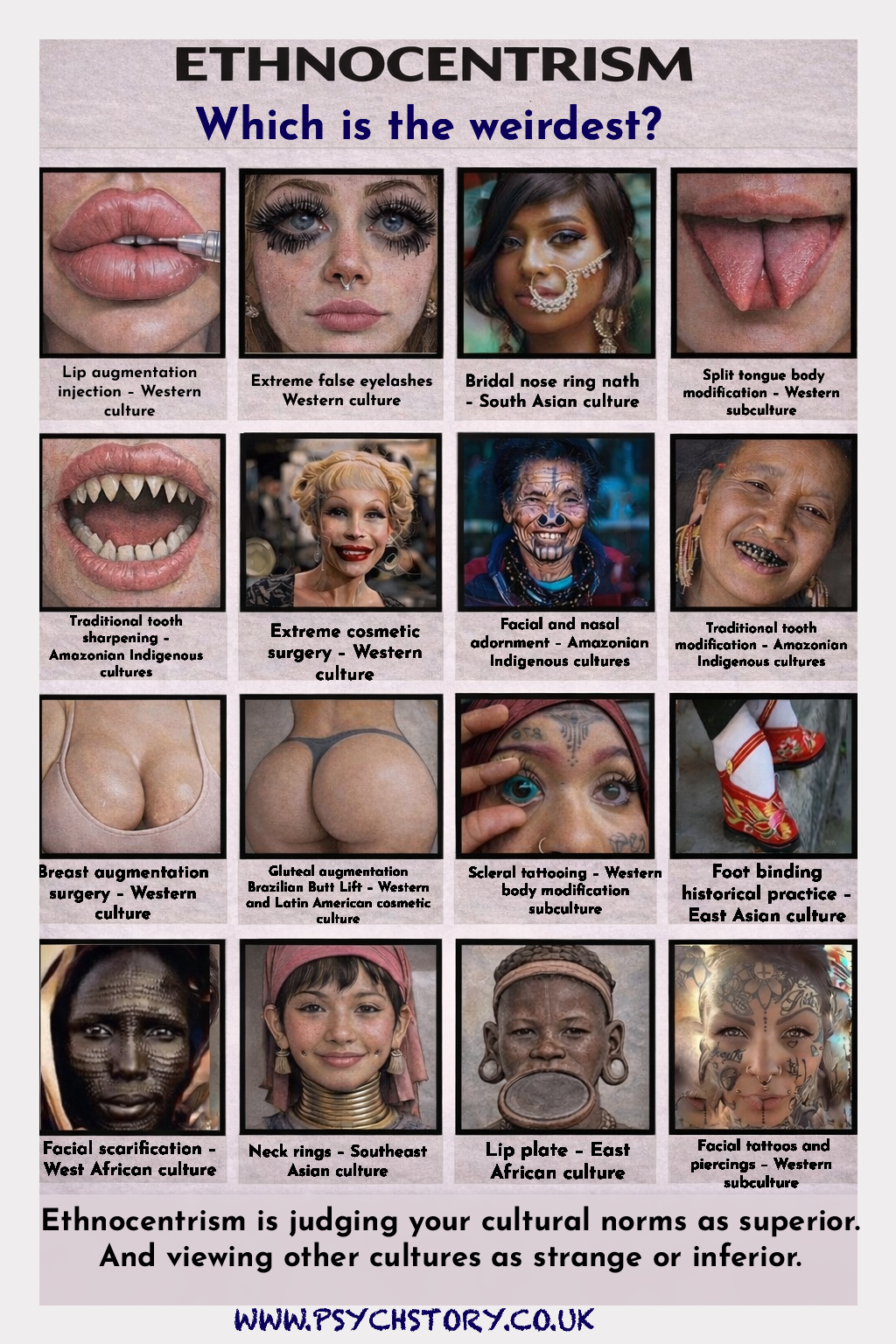

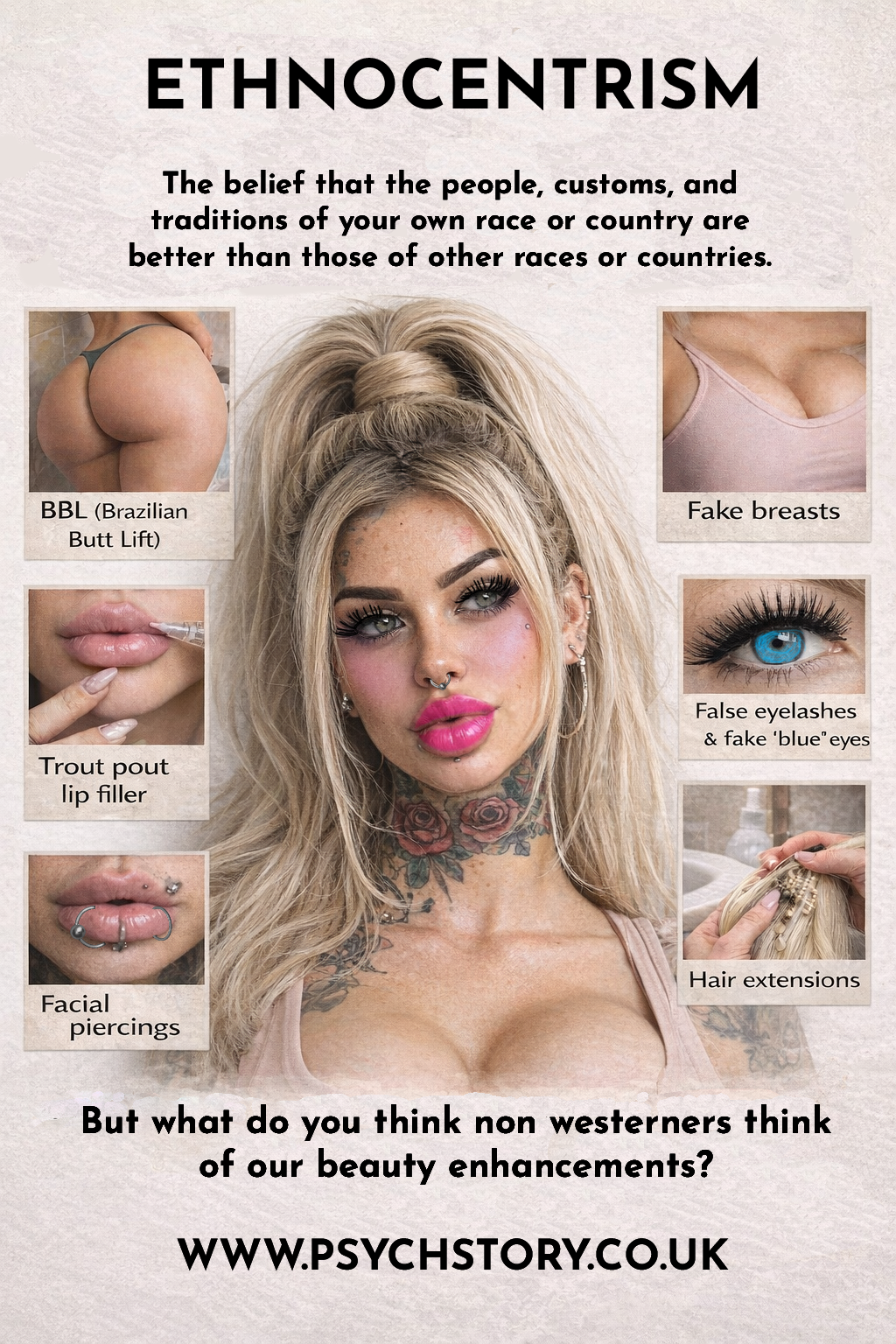

ETHNOCENTRISM

Ethnocentrism refers to the tendency to judge other cultures according to the standards of one’s own culture (Triandis, 1990). It occurs when researchers assume that their own cultural norms reflect human nature rather than local customs.

One form of ethnocentrism is the assumption that other cultures function in the same way as one’s own. For example, theories such as the reward theory and social exchange theory assume that romantic relationships are formed through individual cost–benefit analysis. This reflects Western individualistic and capitalist assumptions about personal gain and choice. In collectivist cultures, relationships may prioritise family obligations, social cohesion, or long-term stability over individual reward. Applying individualistic assumptions universally is, therefore, ethnocentric.

A second form involves judging other cultures against one’s own moral or aesthetic standards. For example, assuming that cosmetic surgery is normal and universally desirable while mocking cultures where women walk topless and are unconcerned about breast size reflects cultural bias. Standards of modesty, beauty and status are socially constructed. When psychologists treat their own cultural preferences as objective norms, they risk misinterpreting cultural differences as psychological abnormalities.

EUROCENTRISM

Eurocentrism is a specific form of ethnocentrism in which European or Western cultural assumptions are positioned as central or superior. Many early psychological theories were developed in Europe and North America, using predominantly white, middle-class samples. As a result, Western norms about family structure, independence, achievement and gender roles shaped theory development.

The term has historically been extended to American research because of its European intellectual roots. However, modern American academia is ethnically diverse. The central issue is not geographical location but whether research assumes a Western industrialised worldview as universally representative.

When ethnocentrism or Eurocentrism operate within psychology, culturally specific patterns of behaviour risk being presented as universal laws of human functioning

AFROCENTRISM

Afrocentrism is a perspective that centres African history, values and worldviews rather than interpreting them through European frameworks. It emerged partly as a corrective response to Eurocentrism, which had historically marginalised or misrepresented African cultures.

In psychology, an Afrocentric approach may emphasise communal identity, spirituality, extended family structures and collective responsibility as normative rather than deviant. It challenges Western individualistic assumptions about autonomy, competition and nuclear family models.

However, Afrocentrism can also become biased if it treats African cultural values as inherently superior or universally applicable. Just as Eurocentrism assumes Western norms are central, Afrocentrism risks replacing one cultural centre with another.

The key issue for psychology is not which cultural lens dominates, but whether any single cultural framework is presented as universally valid. Cultural relativism attempts to prevent this by requiring that behaviour be interpreted within its own cultural context rather than through externally imposed standards

SOLUTIONS TO CULTURAL BIAS

CULTURAL RELATIVISM

Cultural relativism is the position that behaviour, beliefs and values must be understood within the context of the culture in which they occur. A practice should not be judged against external standards, but interpreted according to the internal logic, history and social structure of that cultural group.

In psychological research, cultural relativism challenges universal claims. Concepts such as intelligence, attachment, romantic love, independence, mental illness or morality may not have identical meanings across societies. A behaviour considered normal in one culture may be labelled deviant in another. Cultural relativism, therefore, requires psychologists to ask whether their definitions, measures and interpretations are culturally bounded.

However, strong cultural relativism can complicate cross-cultural comparisons. If every behaviour is entirely culture-specific, it becomes challenging to identify universal processes. Psychology, therefore, operates in tension between universalism and cultural specificity.

WAYS OF RESEARCHING CULTURE: IMPOSED ETIC, DERIVED ETIC AND EMIC

In anthropology and psychology, the distinction among imposed etic, derived etic, and emic refers to three perspectives used to study human behaviour across cultures. The terms originate from the linguist Kenneth Pike (1954), who adapted them from phonetics (universal sounds across languages) and phonemics (language-specific sound systems).

Broadly, these approaches differ in how they treat universality and cultural specificity.

An etic perspective examines behaviour from an outsider standpoint. It looks for general principles that apply across cultures. However, there are two forms of etic research.

An imposed etic assumes universality from the outset. It applies existing theories or measurement tools developed in one culture to another culture without substantial adaptation.

A derived etic, by contrast, investigates behaviour within each culture first and only then identifies universal patterns. Universality is established through cultural comparison rather than being assumed a priori.

An emic approach adopts an insider perspective. It assumes that behaviour can be understood only within its cultural context and does not automatically attempt cross-cultural generalisation.

The distinction is important because it determines whether research respects cultural meaning or risks imposing external assumptions

ORIGINS OF THE TERMS

The terms etic and emic were introduced by the linguist Kenneth Pike (1954). They were derived from two concepts in linguistics: phonetics and phonemics.

Phonetics refers to the study of speech sounds that are physically possible across all human languages. These sounds are universal. All infants are born with the capacity to hear and discriminate a wide range of phonetic contrasts. For example, babies can initially distinguish between sounds used in many different languages, even those not spoken in their home environment. In this sense, phonetics represents what is potentially universal in human capacity.

Phonemics, by contrast, refers to the sound system within a particular language. As infants are exposed to one linguistic environment, they gradually become specialised in detecting and producing the sounds that are meaningful in that language. Sounds that are not used in their linguistic environment become harder to discriminate. This narrowing occurs during a sensitive or critical period in early development. After that period, learning new phonemic distinctions becomes significantly more difficult.

Pike used this distinction metaphorically.

Etic parallels phonetics. It refers to behavioural features that may be universal across human groups. An etic approach looks for patterns that transcend local meaning systems.

Emic parallels phonemics. It refers to culturally specific meanings and structures that are understood from within a group. An emic approach examines how behaviour is organised and interpreted inside that cultural system.

The analogy is precise: phonetics identifies what humans can do universally; phonemics identifies how that universal capacity is structured differently within particular systems. Likewise, etic approaches seek universal behavioural processes, whereas emic approaches examine how those processes are patterned and interpreted locally.

This linguistic origin is important because it clarifies that the distinction was never meant to imply that one approach is correct and the other incorrect. Instead, it highlights the tension between universal human capacity and culturally specific expression

WAYS OF RESEARCHING CULTURE: WAYS OF RESEARCHING CULTURE:

In anthropology and psychology, the distinction among imposed etic, derived etic, and emic refers to three perspectives used to study human behaviour across cultures. The terms originate from the linguist Kenneth Pike (1954), who adapted them from phonetics (universal sounds across languages) and phonemics (language-specific sound systems). Broadly, these approaches differ in how they treat universality and cultural specificity. An etic perspective examines behaviour from an outsider standpoint. It looks for general principles that apply across cultures. However, there are two forms of etic research. An imposed etic assumes universality from the outset. It applies existing theories or measurement tools developed in one culture to another culture without substantial adaptation. A derived etic, by contrast, investigates behaviour within each culture first and only then identifies universal patterns. Universality is established through cultural comparison rather than being assumed a priori. An emic approach adopts an insider perspective. It assumes that behaviour can be understood only within its cultural context and does not automatically attempt cross-cultural generalisation. The distinction is important because it determines whether research respects cultural meaning or risks imposing external assumptions.

EMIC, DERIVED ETIC AND IMPOSED ETIC

This is one of the most confusing areas in cultural psychology because textbooks do not always cleanly separate the approaches, and some teachers describe them in slightly different ways. However, the conceptual differences matter because they determine whether research respects cultural context or imposes assumptions. The core issue is whether universality is assumed at the outset or tested and concluded only after culturally sensitive work.

IMPOSED ETIC

Imposed etic assumes that human behaviour is universal and that culture is largely irrelevant to the underlying construct. One set of psychological concepts and one set of measurement tools are applied across cultures with minimal adaptation. This is often framed as scientific objectivity, but it is effectively a hard nature position: if behaviour is the same everywhere, then variation is treated as noise, error, or deficit. Imposed etic commonly involves exporting Western constructs and instruments globally. Examples include IQ tests, the MMPI, the Global Assessment of Functioning, the Eating Attitudes Test, the Body Shape Questionnaire, standardised attitude scales, and procedures such as the Strange Situation, which are used cross-culturally as if the construct and its behavioural indicators have identical meaning everywhere. This approach assumes universality in advance. It does not wait to discover whether the construct travels well.

CRITIQUE OF IMPOSED ETIC:

WHY THE NATURE ASSUMPTION FAILS

Imposed etic often smuggles in a biological assumption: that the construct is biologically fixed and therefore measurable in the same way across contexts. That is increasingly difficult to defend. Human development is plastic. Cognition and behaviour are shaped by schooling, nutrition, disease burden, stress exposure, language environment, parenting practices, ecological demands, and social roles. Epigenetic mechanisms exist precisely because environments regulate gene expression across development. If development is plastic, then measured differences between groups cannot be treated as direct readouts of biology. Temporal validity also matters. Even within the same country, behaviour varies across cohorts as economies, technology, schooling, family structures, and norms evolve. A tool developed over one decade may not measure the same thing in the next, even before culture is taken into account. Assuming cultural stability while ignoring temporal change is methodologically incoherent.

CRITIQUE OF IMPOSED ETIC: THE IQ EXAMPLE IQ

Testing clearly demonstrates the imposed etic problem. Intelligence tests are presented as measuring general cognitive ability, yet many tasks reflect Western schooling and cultural capital. It takes roughly eleven years of formal education to develop the literacy, numeracy, and abstract reasoning routinely assessed in standard IQ tests. Comparing individuals from regions affected by poverty, interrupted schooling, malnutrition, chronic illness such as malaria, and different linguistic environments with Western samples is not a clean test of biology. Lower scores are easily produced by deprivation and limited schooling. Treating them as genetic deficits is methodologically flawed. Even tasks that appear neutral contain cultural knowledge. Consider an odd one out task, such as which of the following items does not belong: violin, viola, drums, guitar. The expected answer is drums, as it is a percussion instrument rather than a stringed instrument. Yet a person unfamiliar with orchestral categories may choose viola on the grounds that they do not know it is an instrument. That is a logically defensible deduction from their knowledge base. Marking it as low intelligence is essentially a sign of unfamiliarity with middle-class Western cultural reference points. Similarly, anagrams that depend on cultural knowledge, specific vocabulary, and measures of exposure and education as much as on reasoning. The same critique extends beyond IQ. Eating disorder measures may assume thinness anxiety as pathological, yet body ideals differ across societies. Personality inventories assume Western trait structures.

THE STRANGE SITUATION

Attachment classifications may reflect middle-class Western norms about separation, independence, and stranger contact. For example, "The Strange Situation" was developed within a Western cultural framework, in which independence and exploration are associated with secure attachment. However, this assumption may not apply across all societies, making the study ethnocentric. The procedure is an etic tool, meaning it applies a research method developed in one culture (Western societies) to others without considering cultural differences. It assumes that securely attached infants should feel comfortable exploring their surroundings while using their mother as a safe base. However, exploration may not be encouraged in many non-Western cultures due to environmental risks. For example, in ancestral environments or regions where predators and poisonous plants pose a threat, remaining close to a caregiver would be a more adaptive survival strategy. In such cultures, the most appropriate response may be an attachment style classified as resistant in a strange situation, where the child clings to the caregiver and shows distress when separated. Another Western assumption in the study is that it is normal for babies to sleep separately from their parents. In contrast, many cultures practice co-sleeping for extended periods. Historically, leaving a baby alone in a separate space would have been extremely dangerous, as it could have resulted in an attack by animals or abandonment. The idea that a secure attachment is linked to a child’s ability to tolerate brief separations may be a cultural construct rather than a universal measure of attachment security. Because the study was designed around Western parenting norms, its findings may lack population validity when applied to societies in which different caregiving practices are the norm. The assumption that independent exploration is always a sign of security overlooks the reality that, in some cultures, remaining close to a caregiver is not an indicator of insecurity but an adaptive survival strategy. Therefore, attachment research should consider cultural context rather than treating Western norms as the universal standard.

DERIVED ETIC

Derived etic is often described as mostly nature with some nurture. It assumes there may be universal underlying processes but accepts that culture alters how those processes are expressed and observed. The crucial distinction from imposed etic is methodological. Universality is not assumed at the start. Instead, behaviour is studied within each culture first, using culturally sensitive methods or adapted tools, and only then are comparisons made to identify shared patterns. Attachment is a standard example. Attachment may exist across societies, but the behaviours that signal security and insecurity may differ depending on norms of proximity, separation and caregiving. This is where the Strange Situation becomes a useful critique. The procedure classifies resistant attachment as characterised by intense distress during separation and difficulty being soothed during reunion. Yet what does that behaviour represent? It could reflect inconsistent caregiving. It could reflect overprotective caregiving. Or it could reflect a culture where separation is rare and therefore unusually distressing. The Strange Situation does not cleanly separate these possibilities, which weakens interpretation. Takahashi’s work in Japan illustrates this. Many infants were classified as resistant, yet Japanese caregiving often involves close physical proximity, and separation is culturally uncommon. Distress may therefore reflect the unnaturalness of the situation rather than insecure attachment. Reports that some sessions were halted due to severe distress underline that the procedure itself may not travel across cultures as a neutral test. Germany raises a parallel issue. High avoidant classifications have been linked to cultural values emphasising early independence and emotional self-control. Again, what appears to be insecurity in one context may be adaptive behaviour in another. A significant nuance lies beneath these examples. Sometimes researchers reinterpret Japanese distress as culturally normal, yet leave Western subcultures or lower-income groups with similar behaviours classified as insecure. That selective cultural adjustment undermines objectivity. Either the categories are universal and should apply consistently, or they are culture-bound and should not be treated as universal benchmarks. Derived etic is preferable to imposed etic, but it still struggles to determine whether conclusions about universality are genuinely warranted or merely assumed.

EMIC APPROACH

Emic is culture-specific and aligns strongly with a nurture perspective. It assumes that behaviour and mental life can be understood properly only within the culture that produces them. Concepts, meanings and norms are defined from the inside, by members of the culture. Research tools are developed within that cultural framework, and findings are not assumed to generalise. This approach can be pushed further. It can be argued that some cultural practices and meanings are not fully intelligible to outsiders, and that only people embedded in that culture can interpret them without distortion. Beauty standards make this intuitive. Teeth sharpening in some Amazonian groups, scarification or body modification practices in some African communities, and cosmetic surgery norms in Western societies are all treated as attractive within their own meaning systems. If an outsider experiences immediate disgust or incomprehension, that may reveal ethnocentrism rather than irrationality in the target culture. Emic, therefore, protects meaning and context, but it limits cross-cultural comparison. It prioritises validity within a culture over generalisation across cultures.

CRITIQUE OF THE EMIC APPROACH

Although the emic approach protects cultural meaning and avoids imposing external categories, it is not without serious limitations.

First, it restricts generalisation. If behaviour can only be understood within its own cultural framework, then comparison across cultures becomes impossible. Psychology, however, seeks broader explanatory principles. A purely emic position fragments knowledge into isolated cultural case studies. It becomes difficult to determine whether any psychological process is universal or whether all behaviour is entirely culture-bound.

Second, it risks relativism. If every belief, norm or practice must be understood solely within its cultural context, it becomes difficult to evaluate practices that may be harmful. For example, extreme gender restrictions, corporal punishment, or rigid honour-based systems may be defended as “culturally meaningful.” An uncritical emic stance can blur the boundary between understanding and justification. Cultural relativism must not become moral relativism.

Third, emic research can lack objectivity. By prioritising insider perspectives, it may privilege subjective interpretation over systematic measurement. Researchers embedded within a culture may struggle to question taken-for-granted assumptions. Complete immersion does not guarantee neutrality. Cultural insiders may normalise practices that an external perspective would interrogate.

Fourth, emic approaches can be methodologically weak. Because they often rely on qualitative data, interviews, and participant observation, they may lack reliability and replicability. Findings may be difficult to compare across studies because constructs are defined differently across cultural contexts.

Fifth, emic research does not eliminate bias; it relocates it. An insider researcher may still hold class, gender, political or religious biases within their own culture. Cultural membership does not automatically ensure interpretative accuracy. Cultures are not homogeneous, and internal disagreement is common.

Finally, a strictly emic approach may overstate differences. While cultures vary, there is strong evidence for biological and cognitive universals, such as attachment systems, emotional expressions, language acquisition capacity, and certain perceptual processes. Denying all universality risks ignoring the evolutionary and neurobiological foundations of behaviour.

In summary, the emic approach maximises cultural sensitivity and protects against ethnocentrism, but at the cost of generalisability, objectivity, and theoretical integration. It is strongest when combined with a cautious derived etic approach, rather than adopted as an absolute methodological position

EVALUATIVE SUMMARY: THE ORIGINAL SEQUENCE

The imposed etic, emic and derived etic distinctions were never meant to function as isolated positions. They describe stages of enquiry.

You cannot properly research behaviour by adopting only one approach.

If you begin and end with an imposed etic, you assume universality before testing it. Constructs are applied immediately and differences are interpreted within a pre-existing framework. That short-circuits the investigation.

If you remain purely emic, you generate detailed, internally valid accounts of behaviour within a group, but you cannot determine whether what you have observed is specific to that group or general across humans. You stop at the description.

The intended logic is sequential.

Etic-1: Begin with a provisional framework or hypothesis.

Emic phase: Investigate how the construct operates in the group under study. Allow definitions, meanings and behavioural indicators to adjust.

Etic-2 (derived etic): Return to comparison only after that grounding. Universality is then concluded, revised or rejected based on evidence.

The critical distinction is not a matter of preference. It is about order.

The imposed etic assumes universality first and measures immediately.

Derived etic tests universality after investigation.

Emic provides the grounding that makes the final comparison meaningful.

Proper scientific enquiry requires movement through the sequence. Skipping stages produces either premature generalisation or isolated description.