RELIABILITY

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY

Reliability and validity underpin everything that psychologists do – without them, research would be worthless

The principles of validity and reliability are fundamental cornerstones of the scientific method.

Together, they are at the core of what is accepted as scientific proof by scientists and philosophers alike. By following a few basic principles, any experimental design will withstand rigorous questioning and scepticism.

SPECIFICATION:

Reliability across all methods of investigation. Ways of assessing reliability: test-retest and inter-observer; improving reliability.

WHAT IS RELIABILITY?

Does a driving test measure your competence to drive on the road or is it a measure of your ability to pass the driving test? Would you be able to pass it again in six months’ time? Would you do better? Is it a reliable and valid test?

The idea behind reliability is that any significant results must be more than a one-off finding and be repeatable. Other researchers must be able to perform exactly the same experiment, under the same conditions and generate the same results. This will reinforce the findings and ensure that the wider scientific community will accept the hypothesis. Without this replication of statistically significant results, the experiment and the research have not met all the requirements for testability.

Reliability essential for research to be accepted as scientific. For example, if you are performing an experiment where time is a factor, you will be using some type of stopwatch. Generally, it is reasonable to assume that the instruments are reliable and will keep true and accurate time. Psychologists take measurements repeatedly to minimise the risk of error and maintain validity and reliability.

Any experiment that relies on human judgment is always going to come under scrutiny.

In a nutshell ……

If a measurement is not reliable, then research cannot be valid or ‘true.

We need to be able to measure or observe something time after time and produce the same or similar results

For example, you want to measure intelligence in a 16-year-old boy, so you give him an IQ test. If that same boy sits the test on several occasions and the results don’t change each time, then that test has reliability

If you test the same boy several months later and his score remains consistent, you can say the test is reliable. Incidentally, it might still lack validity. The second score might just be measuring what a person has learned since taking the first test.

THERE ARE TWO TYPES OF RELIABILITY

INTERNAL RELIABILITY

Internal reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. It asks whether different parts of a test or questionnaire produce similar results. For example, items designed to measure the same trait should give consistent responses rather than contradict each other.

EXTERNAL RELIABILITY

External reliability refers to the consistency of results across time, researchers or situations. It asks whether the same study or measure would yield similar results if repeated, retested later, or conducted by different investigators.

INTERNAL RELIABILITY

Internal reliability refers to consistency within the same measure or instrument. It asks whether different parts of the same test or measurement produce similar results. If the components of a measure are all assessing the same thing, the results should agree with each other.

A depression questionnaire is a clear example. A test designed to measure depression contains several questions about mood, sleep, motivation and enjoyment. If a person reports severe sadness, loss of pleasure and low energy across most items, the responses are internally consistent and the test shows good internal reliability. However, if the same person scores very high on some depression items but very low on others that measure the same construct, the test lacks internal reliability because its items are not producing consistent outcomes within the measure itself.

An IQ test also demonstrates internal reliability. IQ is not measured by a single question but rather through multiple subtests, such as reasoning, vocabulary, and pattern recognition. These parts are intended to reflect general cognitive ability. If a person scores similarly across subtests, the test shows strong internal reliability because different parts of the same instrument agree. If scores vary wildly without explanation, internal reliability is weakened because the components are not producing consistent results.

Weighing yourself provides a simpler analogy. Imagine standing on the same weighing scale several times in succession. If the scale gives nearly identical readings each time, the measurement is internally consistent. The device is producing stable results within the same measurement process. If the weight changes dramatically each time without a reason, the measurement lacks reliability.

All three examples show the same principle: internal reliability concerns whether the measure itself behaves consistently, not whether it is correct or meaningful

IMPROVING INTERNAL RELIABILITY

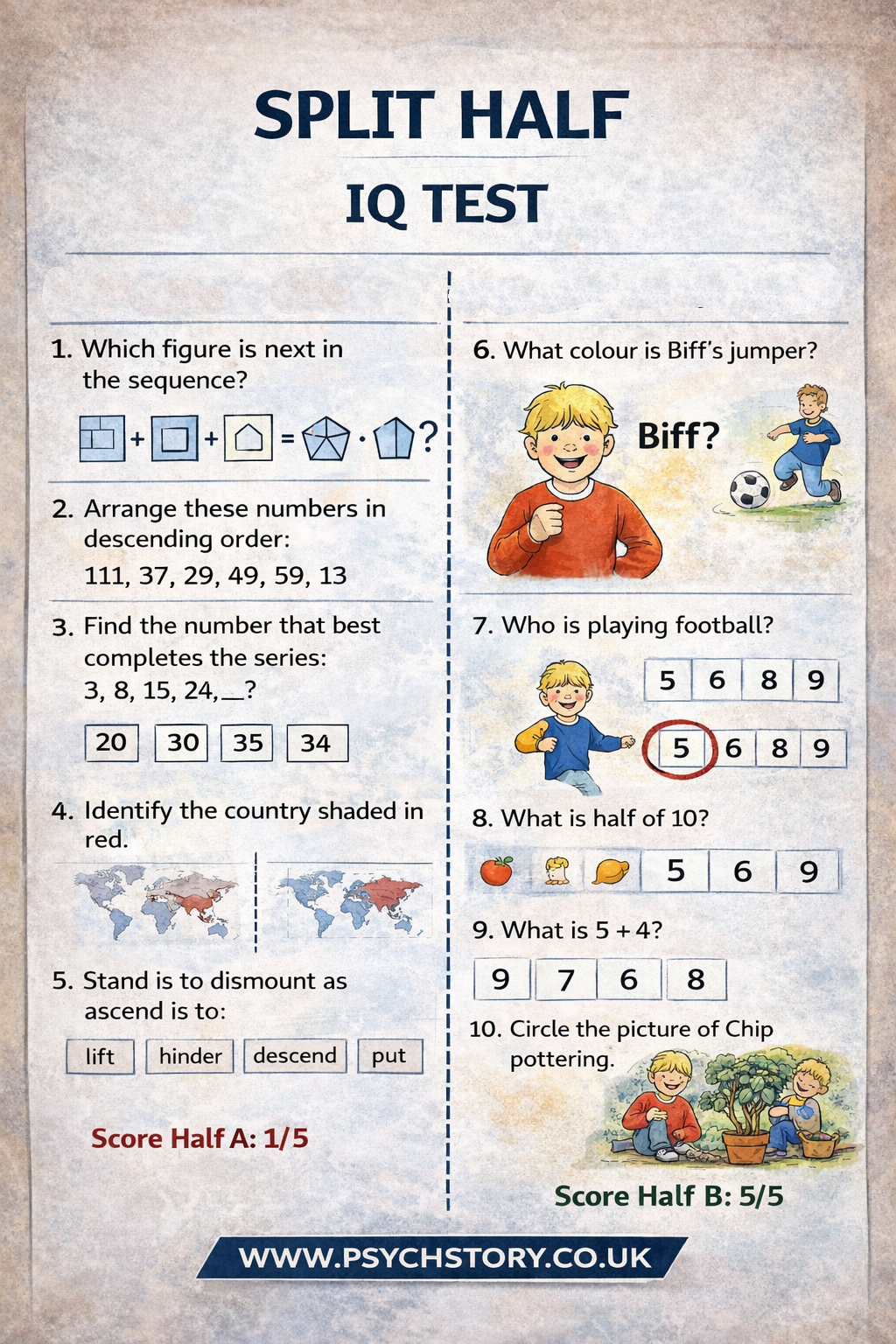

SPLIT-HALF METHOD

A test or questionnaire is divided into two halves (for example, odd versus even items), and the scores from each half are correlated. If both halves produce similar results, the measure shows good internal reliability because different parts of the same instrument are producing consistent outcomes.

CRONBACH’S ALPHA

Cronbach’s alpha assesses internal consistency by examining how closely related all items within a scale are. A high alpha value indicates that items are measuring the same underlying construct. Items that weaken consistency can be revised or removed.

INCREASING THE NUMBER OF RELEVANT ITEMS

Using multiple items that assess the same construct improves internal reliability because random errors affecting individual questions are reduced when responses are combined across a scale.

CLEAR AND UNAMBIGUOUS QUESTIONS OR CODING CATEGORIES

Items or categories must be clearly worded and interpreted consistently. Ambiguous questions or vague coding categories lead to inconsistent responses or classifications, lowering internal reliability.

STANDARDISED SCORING OR CODING PROCEDURES

Responses must be scored or coded using identical rules for all data. Clear scoring criteria ensure that variation reflects participant responses rather than inconsistent interpretation.

EXTERNAL RELIABILITY

External reliability refers to the extent to which a measure or study produces consistent results when repeated. It asks whether the same findings would be obtained on another occasion, with another researcher, or in another setting, provided the procedures remain the same.

It is fundamental to science because scientific knowledge must be reproducible. A finding that only appears once, in one laboratory, with one researcher, cannot be treated as reliable evidence. Science progresses by building cumulative knowledge, and that is only possible if results are stable when repeated.

External reliability is demonstrated in several ways. Test-retest reliability occurs when the same participants complete the same measure on two occasions and obtain similar scores. For example, if a person takes an IQ test twice within a short period and their scores are similar, the test shows external reliability across time.

Inter-rater reliability occurs when different researchers or clinicians independently assess the same behaviour or diagnosis and reach similar conclusions. If two psychiatrists diagnose the same patient with schizophrenia using the same criteria and agree, reliability across raters is demonstrated.

Replication at the level of whole studies also reflects external reliability. When independent researchers repeat an experiment using the same procedures and obtain similar results, the original findings are considered reliable.

The distinction is important. Replication is the act of repeating a study. External reliability is the consistency shown when that repetition occurs. Without external reliability, research findings are unstable, cannot be trusted, and cannot contribute to scientific understanding

IMPROVING EXTERNAL RELIABILITY

External reliability is improved by ensuring that results remain consistent when measurement or research is repeated across time, researchers and studies. Because science depends on reproducibility, researchers must show that findings are not one-off outcomes produced by chance, timing or individual researchers.

TEST RETEST RELIABILITY

Participants complete the same test on different occasions, and the two sets of scores are correlated. A strong positive correlation indicates good external reliability, as the measure yields stable results over time.

Timing is crucial. The interval must be long enough to prevent participants from simply remembering previous answers, but short enough that the trait being measured has not genuinely changed. For example, intelligence should remain relatively stable over short periods, whereas mood or anxiety may naturally fluctuate, lowering reliability even when the test itself is sound.

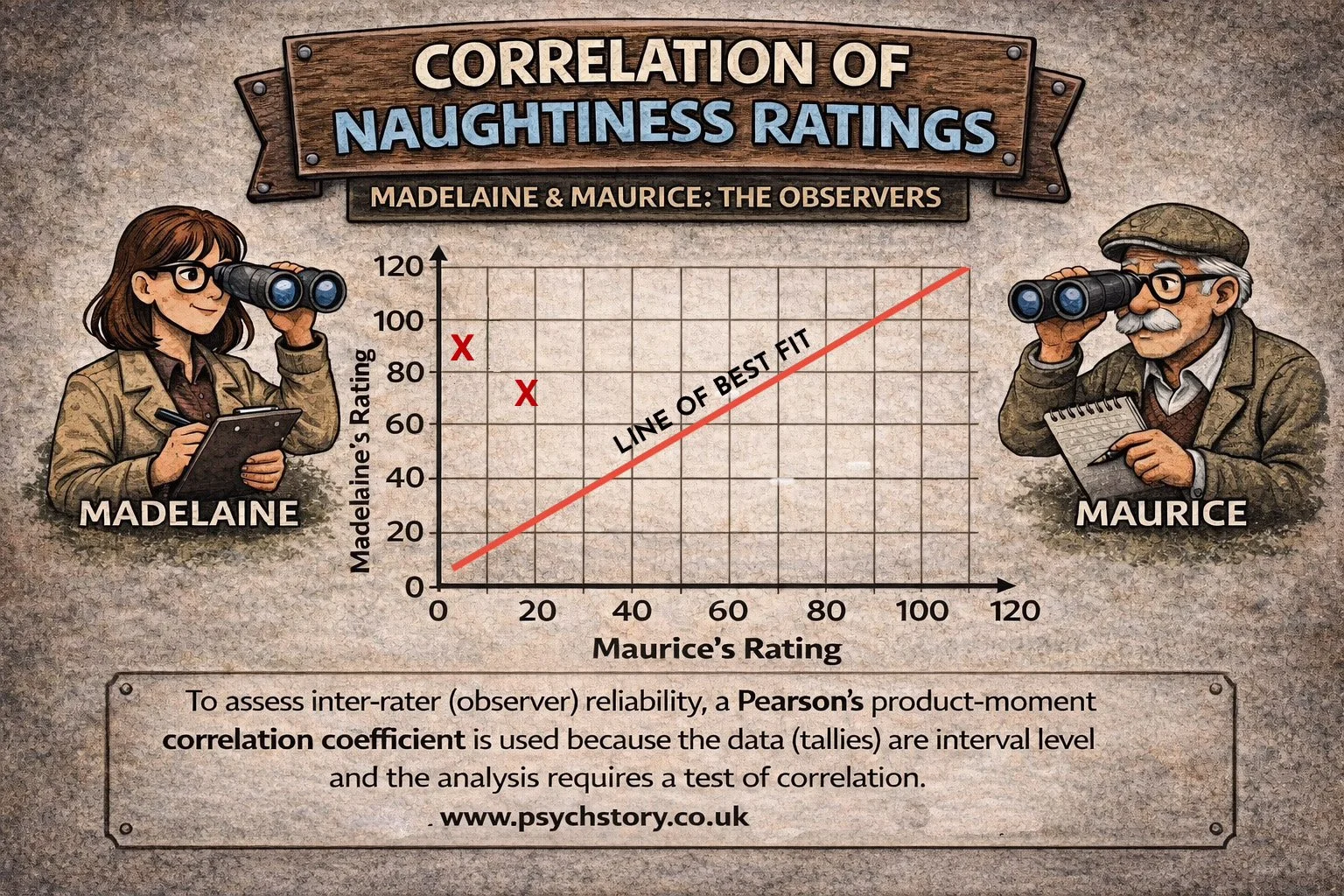

INTER RATER RELIABILITY

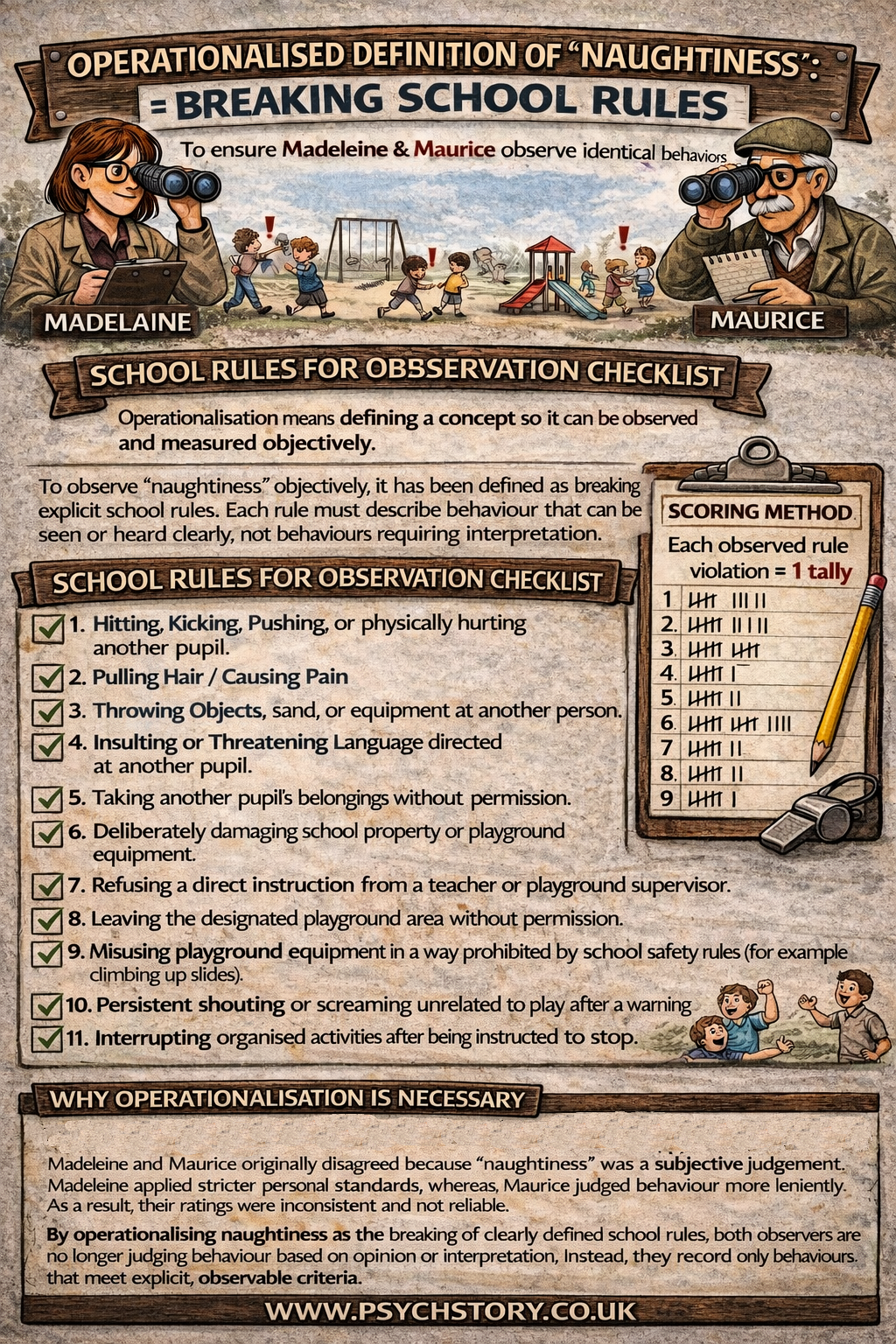

External reliability improves when different researchers or clinicians produce the same results using the same procedures. Clear operationalised categories, structured interview schedules and observer training help ensure that behaviour or responses are interpreted consistently. For example, two psychiatrists using the same diagnostic criteria should reach the same diagnosis when assessing the same patient.

STANDARDISED PROCEDURES

Studies should use identical instructions, testing conditions and scoring rules so that repetition does not introduce variation. If procedures change between occasions or researchers, differences in results may reflect methodological variation rather than genuine inconsistency.

REPLICATION

Repeating a study using the same method allows researchers to determine whether findings are reproducible. If independent researchers obtain similar results, external reliability is strengthened. Replication demonstrates that outcomes are not dependent on a single researcher, a single sample, or a single occasion.

META ANALYSIS

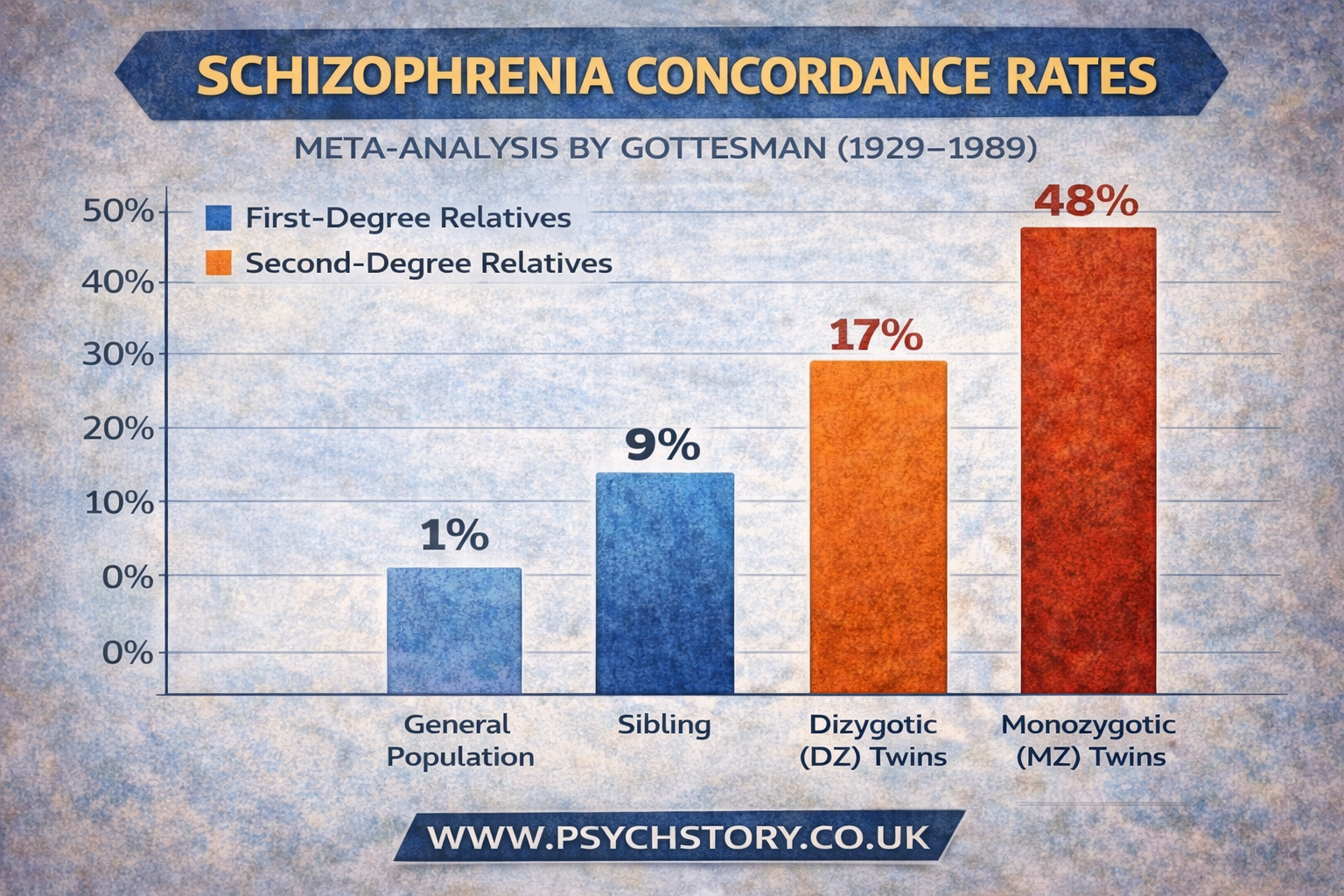

Meta-analysis strengthens external reliability by examining results across many replications. By statistically combining findings from multiple studies conducted in different locations, with different researchers and participants, psychologists can determine whether an effect appears consistently across research. Consistent patterns across studies indicate that findings are reliable beyond a single investigation.

External reliability, therefore, rests on repeatability across time, raters and independent studies. When results remain stable under repetition, they form a dependable basis for scientific knowledge

IMPROVING RELIABILITY IN RESEARCH OVERALL

Good research aims to maximise reliability by ensuring that procedures, measurements and interpretations are consistent and repeatable. Reliability improves when studies are conducted in a stable, standardised and systematic manner so that similar results would be obtained if the research were repeated.

Standardising instructions ensures that every participant receives the same explanation and guidance. If instructions vary, differences in results may reflect misunderstanding rather than genuine differences in behaviour. Clear, identical instructions improve consistency among participants and among researchers who may later replicate the study.

Operationalising variables strengthens reliability by clearly defining what is being measured. Behaviours must be specified in observable and measurable terms. For example, defining aggression as “hitting, pushing or shouting above a specified volume” reduces subjective interpretation. This improves inter-rater reliability because different observers are more likely to classify behaviour similarly.

Standardising data collection through well-trained observers also increases reliability. When researchers are trained to follow the same procedures and apply the same coding rules, variation caused by individual judgment is reduced.

Taking multiple measurements per participant and calculating an average helps reduce the influence of random error. A single score may be affected by temporary factors such as fatigue or distraction, whereas averaged scores are more stable.

Pilot studies allow researchers to identify unclear instructions, ambiguous questions or procedural weaknesses before the main study begins. Refining materials and procedures at this stage improves the consistency of the final research design.

Carefully checking data recording and interpretation prevents errors that could reduce reliability. Inconsistent scoring or recording can create artificial variation in results.

Finally, thorough training of researchers in the use of materials and procedures ensures that the study can be repeated accurately by others. When methods are clear, standardised and consistently applied, reliability is strengthened and findings become scientifically dependable