SELF DISCLOSURE

FACTORS AFFECTING ATTRACTION IN ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS:

SPECIFICATION: SELF-DISCLOSURE

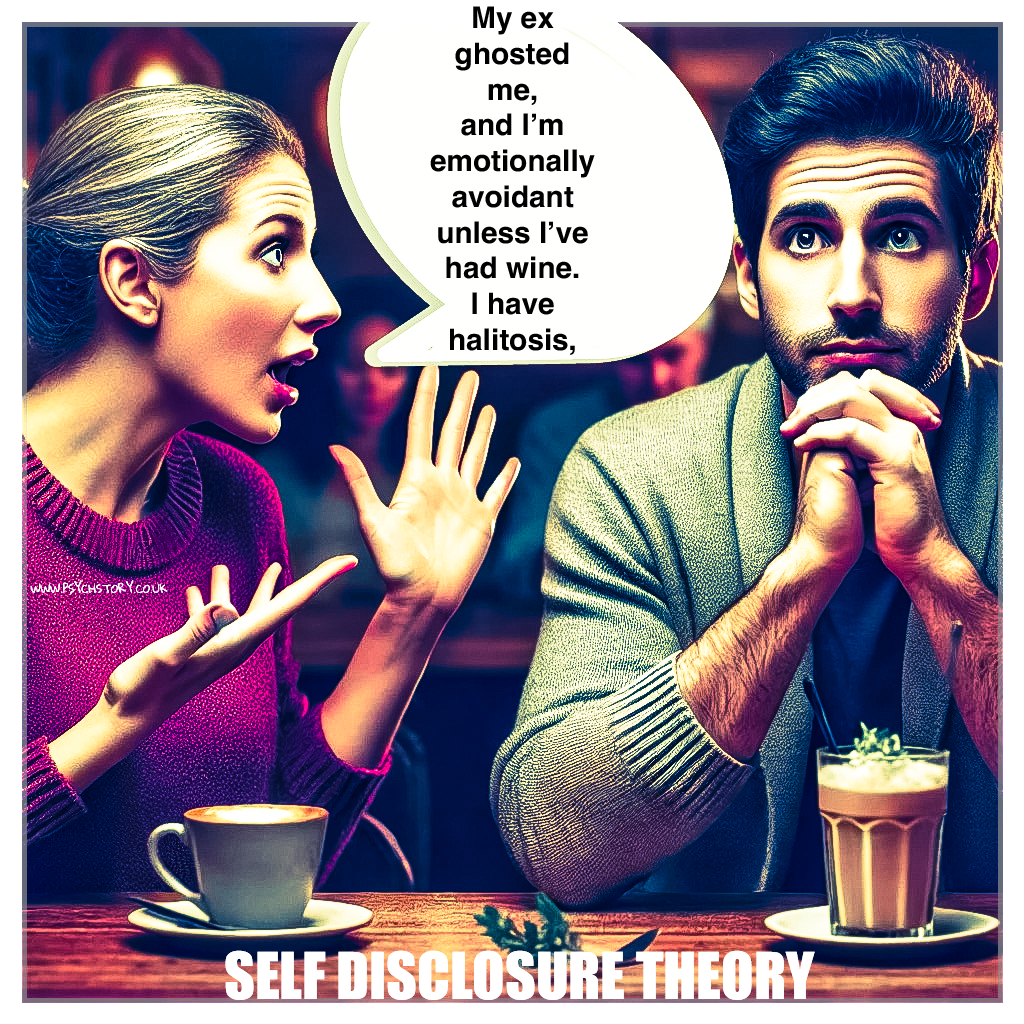

The importance of sharing personal information and feelings in building intimacy and attraction.

Self-disclosure refers to revealing personal information about yourself. Romantic partners share more about their authentic selves as their relationship develops. When used appropriately, self-disclosures about one’s deepest thoughts and feelings can help strengthen a romantic bond.

MAIN IDEA

In the early stages of a relationship, people are naturally curious about their partner. The more they learn, the closer they often feel. Individuals open a window into their inner world by sharing personal thoughts, emotions, and experiences. This process allows partners to understand each other better, strengthening their emotional connection.

Self-disclosure plays a crucial role beyond the initial stages of attraction. It fosters trust and intimacy, helping relationships develop and endure. However, people are often cautious about what they reveal, especially at the beginning. When used wisely and reciprocated appropriately, self-disclosure can strengthen relationships and make them more fulfilling.

SOCIAL PENETRATION THEORY

Social Penetration Theory (Altman and Taylor, 1973) formally explains how self-disclosure operates as the primary mechanism through which intimacy develops in romantic relationships. It proposes that closeness is achieved through gradual “penetration” into each other’s inner lives, facilitated by increasingly personal and emotionally significant disclosures.

This theory views self-disclosure as unfolding across two dimensions: breadth (the range of topics discussed) and depth (the level of intimacy or emotional sensitivity within those topics). Early interactions typically involve broad but shallow disclosures—topics like hobbies, daily routines, or surface-level opinions. As the relationship progresses, the disclosure deepens, encompassing more vulnerable areas such as values, fears, aspirations, and emotional insecurities.

Altman and Taylor use the metaphor of an onion to describe this layering of the self. Each layer peeled back represents a new level of psychological intimacy. Trust is built gradually as each partner reveals and receives information. Crucially, this process is reciprocal—mutual disclosure is necessary to maintain balance and promote emotional safety. When one partner opens up, the other is expected to respond in kind, reinforcing a cycle of vulnerability and trust.

In this framework, self-disclosure is not just a sign of intimacy but a driver of it. The theory argues that meaningful closeness cannot develop without this progressive exchange. Therefore, romantic partners are expected to occupy the most central layers of the “onion”—the parts of the self that are hidden from most others. The more deeply one is known—and accepted—the more secure and emotionally bonded the relationship becomes.

KEY CONCEPTS IN SOCIAL PENETRATION THEORY

BREADTH AND DEPTH OF SELF-DISCLOSURE

Altman and Taylor identified two key dimensions of self-disclosure that drive the development of intimacy: breadth and depth.

Breadth refers to the range of topics a person is willing to discuss—such as work, hobbies, family, or daily routines. Depth, on the other hand, concerns how personal or emotionally revealing that information is. While someone might mention that they enjoy reading, a deeper disclosure would involve discussing how certain books shaped their worldview or helped them through a difficult time.

In the early stages of a romantic relationship, conversations usually cover a wide range of topics, but only at surface level. These exchanges are safe and non-threatening, similar to small talk—pleasant but not yet emotionally revealing. This is comparable to the outer layers of the onion in Social Penetration Theory: broad but shallow.

As trust builds and emotional safety is established, couples share more profound disclosures—childhood memories, regrets, fears, hopes, or insecurities. This inward movement through the "layers" reflects growing emotional closeness and vulnerability.

However, depth needs to be carefully paced. Revealing too much too soon—without a foundation of mutual trust or reciprocity—can make the other person feel uncomfortable or pressured, potentially damaging the relationship. When done gradually and reciprocally, though, deep self-disclosure helps strengthen the emotional bond between partners, reinforcing trust, empathy, and commitment.

RECIPROCITY OF SELF-DISCLOSURE

Self-disclosure must be mutual for a relationship to strengthen. Harry Reis and Philip Shaver (1988) emphasised that disclosure should be a balanced process in which both partners contribute equally.

When someone reveals personal thoughts or experiences, they expect their partner to respond with empathy, understanding, and self-disclosure. This reciprocal process reinforces trust and emotional security. If only one partner engages in self-disclosure while the other remains closed off, it may create emotional distance or a sense of disconnection.

A healthy self-disclosure relationship makes both partners feel heard, valued, and emotionally supported. When disclosure is reciprocated, it strengthens intimacy and deepens the emotional bond, helping relationships thrive.

RESEARCH STUDIES ON SELF-DISCLOSURE

Jourard (1971):

Conducted foundational work on the link between self-disclosure and psychological well-being. Found that open self-disclosure led to increased self-acceptance, lower anxiety, and improved interpersonal functioning.

Supports SPT by showing that deeper self-disclosure is psychologically beneficial and reinforces emotional connection.

Altman and Taylor (1973):

Developed Social Penetration Theory. Their studies showed that relationships progress through layers of increasingly personal self-disclosure, following a gradual trajectory from superficial to intimate information.

This is the foundational theory on which SPT is built. It describes the structured, layered process of intimacy formation.

Derlega and Chaikin (1976):

Explored self-disclosure in friendships. Reciprocal self-disclosure led to greater intimacy and relational satisfaction than non-reciprocal disclosure.

Supports SPT by highlighting the importance of mutual exchange in deepening emotional intimacy.

Reis and Shaver (1988):

Highlighted that self-disclosure is a key predictor of intimacy and commitment in romantic relationships, emphasizing mutual, responsive sharing as essential to deepening emotional bonds.

Reinforces SPT’s idea that disclosure must be mutual and emotionally responsive for closeness to develop.

Collins and Miller (1994):

Found that individuals who engage in more self-disclosure are liked more by their partners and are more likely to be attracted to partners who disclose to them. Mutual self-disclosure was positively correlated with satisfaction and longevity.

It supports SPT by showing that disclosure deepens liking and is tied to relationship longevity—both central tenets of the theory.

Laurenceau et al. (1998):

Used diary methods to examine disclosure during periods of relationship stress. Found that open emotional disclosure led to greater cohesion and more adaptive coping within couples.

This study demonstrates that deeper disclosure strengthens bonds during vulnerable times, which aligns with SPT's ‘depth’ principle.

Hass and Stafford (1998) found that 57% of gay men and women in their study cited open and honest self-disclosure as the primary factor in maintaining a committed relationship. This suggests that transparent communication plays a key role in fostering long-term intimacy, regardless of sexual orientation.

Sprecher and Hendrick (2004):

Investigated gender differences. Found that women disclosed more and that mutual disclosure was associated with greater satisfaction for both sexes in romantic relationships.

It supports the reciprocal nature of SPT and highlights how mutual sharing enhances satisfaction.

Tamir and Mitchell (2012):

Using fMRI brain imaging, this study found that self-disclosure activates reward centres in the brain (specifically the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area). This suggests that people may disclose to build intimacy and because it feels inherently rewarding.

This adds a neurological basis to SPT’s view that self-disclosure is socially and emotionally rewarding.

Forest and Wood (2012):

Investigated online self-disclosure on Facebook. People who shared positive updates received more social support, but those who disclosed negative emotions were sometimes perceived as attention-seeking.

Supports SPT by showing that disclosure outcomes are context-dependent—depth and timing matter.

Park et al. (2013):

Analysed the effect of language style matching and depth of disclosure in online dating profiles. Profiles that included emotionally expressive content were rated more authentic and trustworthy.

Reinforces SPT’s claim that deeper emotional content fosters trust and perceived closeness, even digitally.

Frison and Eggermont (2015):

Studied self-disclosure among adolescents on social media. Found that emotional self-disclosure on platforms like Instagram was associated with higher perceived intimacy but also higher vulnerability.

Echoes SPT’s dual-sided nature of depth—greater intimacy but increased emotional risk.

Kahn et al. (2022):

Used experience sampling methodology (real-time smartphone prompts) to track disclosure in daily life. Found that state-level fluctuations in emotional self-disclosure predicted increases in perceived closeness later that same day.

Provides ecological validity for SPT by showing a real-time, daily link between disclosure and intimacy.

EVALUATION OF SELF-DISCLOSURE IN ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS

Several studies support self-disclosure theory and show a strong link between disclosure and relationship satisfaction. For instance, Sprecher and Hendrick (2004) found that dating couples who engaged in mutual self-disclosure reported significantly higher satisfaction levels. Likewise, using a diary method, Laurenceau et al. (2005) found that greater emotional disclosure predicted increased intimacy over time in long-term relationships. These findings suggest that self-disclosure is key to deepening emotional bonds and may contribute to long-term relational maintenance.

However, while the association between self-disclosure and intimacy appears consistent, several methodological issues limit the scientific strength of this research base.

CHALLENGES IN OPERATIONALISING SELF-DISCLOSURE

A major theoretical and methodological issue concerns how self-disclosure is defined and measured. The concept is inherently broad, subjective, and difficult to operationalise. Most studies rely on self-report questionnaires, asking participants to reflect on how much they share with their partner. However, these are vulnerable to subjective bias—what one person views as intimate disclosure (e.g., revealing a childhood trauma), another may see as everyday conversation.

Moreover, self-disclosure is not a uniform construct. The theory tends to treat it as a single measurable behaviour, but in practice, it varies in type (superficial vs. emotional), intent (honest vs. tactical), and context (public vs. private). Some people may disclose trivial facts frequently, while others share significant content more selectively. Others may use disclosure strategically to manipulate or present themselves in a particular light. Without a standardised, objective measure of what constitutes meaningful disclosure, it becomes difficult to assess the reliability of research findings or make comparisons between studies.

This lack of clarity undermines internal validity (what is being measured?) and the theory's scientific testability.

TEMPORAL DYNAMICS OF SELF-DISCLOSURE

Self-disclosure theory often describes disclosure as a gradual and linear process, where intimacy develops steadily as individuals share more personal information. However, disclosure is fluid and context-dependent, influenced by life events, relationship stages, and situational pressures.

Major life transitions, such as marriage, parenthood, or trauma, can either increase or decrease self-disclosure. Similarly, disclosure patterns shift across different relationship stages. New relationships often involve high levels of early disclosure, but as relationships progress, disclosure may fluctuate or stabilise. In long-term relationships, increased openness may be followed by periods of reduced disclosure, where familiarity leads to less frequent deep conversations.

Situational factors, such as stress, conflict, or external demands, can also disrupt disclosure patterns. Some people withdraw from communication during difficult times, while others may increase self-disclosure to seek support. This suggests that disclosure is not a fixed or predictable process but changes over time depending on personal circumstances. The theory could be expanded to account for these shifting dynamics rather than assuming a steady progression of openness leading to greater intimacy.

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH AND ITS LIMITATIONS

Some researchers have used experimental methods, such as the “fast friends” procedure, to improve scientific rigour. In this paradigm, two strangers are instructed to ask and answer increasingly personal questions to simulate rapid intimacy-building. While such studies offer insight into how disclosure affects initial bonding, their ecological validity is limited. These artificial settings lack the complexity, emotional history, and risk of genuine relationships.

In real life, disclosure unfolds over time and is shaped by trust, emotional investment, and social norms. Temporary closeness generated in a lab between strangers cannot be assumed to reflect long-term emotional intimacy in genuine romantic partnerships. As such, while experimental designs offer control, they sacrifice external validity, making it unclear how applicable the findings are to actual relationships.

PREDICTIVE VALIDITY OF SELF-DISCLOSURE

Although research consistently links self-disclosure with higher relationship satisfaction, its ability to predict long-term relationship stability remains unclear.

Other factors that influence relationship longevity include:

Conflict resolution skills – A couple may disclose openly but struggle with managing disagreements.

External stressors – Work, financial stress, or family obligations may weaken a relationship regardless of disclosure levels.

Attachment styles – Securely attached individuals may benefit more from self-disclosure, while avoidant individuals may not rely on it as much.

Thus, while self-disclosure enhances intimacy, it is not the sole determinant of relationship success. The theory would benefit from integrating additional relational factors to improve its predictive power.

CORRELATIONAL AND LONGITUDINAL RESEARCH

Most of the evidence for self-disclosure theory comes from correlational or longitudinal studies, such as those by Sprecher and Hendrick (2004) and Laurenceau et al. (2005). While these studies show that disclosure and satisfaction often occur together, they cannot establish causation. It is equally plausible that people in satisfying relationships are more comfortable disclosing or that other factors—such as personality traits (e.g., extraversion), communication skills, or shared values—account for the observed effects.

The theory cannot predict which couples will remain close or which disclosures will have long-term benefits. Without establishing cause and effect, the claim that disclosure leads to intimacy remains speculative.

SELF-REPORT LIMITATIONS AND SOCIAL DESIRABILITY

The widespread use of self-report methods introduces additional concerns. Participants may overstate their level of disclosure, especially in romantic relationships, due to social desirability bias. Since emotional openness is often viewed as a positive trait, individuals may portray themselves as more disclosive or emotionally connected than they are. This raises questions about the accuracy and authenticity of the data.

In addition, individuals may struggle to recall or assess their disclosure accurately. What feels like “deep sharing” now may not be viewed that way in retrospect, and vice versa. These discrepancies further compromise reliability across studies.

ETHICAL AND PRACTICAL CONSTRAINTS

Ethical and practical limitations also constrain research on self-disclosure. Because self-disclosure often involves emotionally sensitive or private material, participants may filter what they report to researchers. For example, someone may not wish to disclose past trauma or conflict—even anonymously—making it impossible to capture the full range of disclosures occurring in relationships.

Additionally, due to these sensitivities, observational methods are rarely used. Researchers cannot ethically record or intrude upon intimate conversations between partners in real-time. As a result, most research relies on second-hand reports or simulated disclosure rather than actual relational data. This limits both the depth and accuracy of the evidence base.

LIMITED SAMPLE DIVERSITY AND CONTEXTUAL SCOPE

Another problem is the limited scope of the research base. Most studies focus on romantic relationships between young, heterosexual couples in Western contexts. Little research explores how self-disclosure operates in relationships such as therapist-client, workplace, or online dynamics. For example, self-disclosure in digital settings (e.g., social media or dating apps) may be curated, exaggerated, or strategic and follow entirely different norms.

Similarly, research into how disclosure functions in non-Western or collectivist cultures is sparse. In many societies, verbal openness may be discouraged, and emotional support may be communicated non-verbally or indirectly. This suggests that the theory may lack cross-cultural validity and risks imposing Western assumptions onto all relational behaviour..

OVEREMPHASIS ON RECIPROCITY

Reciprocity is a central assumption of self-disclosure theory—suggesting that when one person shares, the other is expected to respond with equal openness. However, in authentic relationships, self-disclosure is often asymmetrical.

Factors that affect reciprocity include:

Power dynamics – One partner may disclose more due to personality differences, emotional needs, or control within the relationship.

Personal comfort levels – Some individuals are naturally more private and may feel uncomfortable reciprocating intimate disclosures.

Social and cultural influences – Some cultures discourage full reciprocity, particularly in intergenerational or professional relationships.

Sometimes, an imbalance in self-disclosure does not indicate a weak relationship; it is simply a result of different communication styles. Thus, the theory may need to account for healthy, non-reciprocal disclosure patterns rather than assuming symmetry as the ideal model.

LACK OF CAUSAL EXPLANATION IN SOCIAL PENETRATION THEORY

While Social Penetration Theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973) offers a compelling description of how intimacy progresses through increasing levels of self-disclosure, it fails to explain why this process occurs in the first place. The theory outlines how emotional closeness develops but provides no underlying framework for whether self-disclosure is a product of biological instinct (nature), social learning (nurture), or both. This limits the theory's psychological depth, as it does not address whether disclosure is an innate human drive or a culturally conditioned behaviour.

NATURAL SELECTION

From an evolutionary perspective, self-disclosure may serve an adaptive function in mate selection and pair bonding. Revealing vulnerabilities and personal truths could act as a trust test, allowing individuals to assess a partner’s loyalty, empathy, and long-term suitability—traits crucial for raising offspring in cooperative pairings. In this sense, self-disclosure may operate like grooming behaviour in primates, strengthening social bonds and reinforcing group cohesion. The emotional risks involved in disclosure make it a reliable signal of sincerity and investment, promoting mutual commitment and reducing the likelihood of infidelity.

CULTURE?

Alternatively, from a socio-cultural or learning theory perspective, patterns of self-disclosure may be shaped by upbringing, media, and social norms. For example, people raised in open, expressive households may be more comfortable sharing feelings, while collectivist cultures may discourage direct emotional exposure in favour of group harmony. However, this explanation struggles to account for universal trends across diverse populations.

One such trend is the consistent finding that women disclose more than men, especially on emotional topics.

If self-disclosure were purely the result of social norms, we would expect more significant variation across cultures. Yet, research shows that women disclose more than men across almost all societies. While cultural expectations may amplify gender differences in disclosure, they are unlikely to be the root cause. Instead, they build upon an already existing biological predisposition.

GENDER DIFFERENCES

Another limitation of the cultural perspective is that even when men and women are socialised in similar ways, gender differences in disclosure persist. Studies have found that in same-sex friendships, women engage in more emotional sharing and verbal communication, whereas men focus on shared activities and problem-solving. This suggests that societal roles do not entirely shape disclosure differences but reflect underlying psychological and neurological differences. This gender difference is robust across most cultures (Sprecher & Hendrick, 2004), raising the question: is this disparity due to socialisation, or does it reflect an evolutionary adaptation?

While cultural factors (e.g. gender role norms) undoubtedly shape communication styles, the fact that women disclose more, even in societies with minimal mass media or Western influence, suggests that biological predispositions may be at play. Women’s greater emotional expressiveness may have evolved to support social bonding, child-rearing cooperation, and maintaining interdependent social networks.

Therefore, although SPT helps map the process of relational development, its lack of a causal or evolutionary foundation weakens its explanatory power. A more robust theory would integrate psychological, biological, and cultural factors to explain why humans are motivated to self-disclose, especially when doing so involves emotional risk.

THE INFLUENCE OF ZEITGEIST ON SELF-DISCLOSURE

While self-disclosure is often treated as a universal, stable process in relationships, it is shaped by the time's prevailing social norms and values—the zeitgeist. The emotional landscape in which people form relationships evolves, meaning what was once considered private or inappropriate to share may now be seen as open and encouraged. This challenges the idea that self-disclosure functions similarly across time or culture.

In earlier generations, particularly in Western societies, emotional restraint was often considered a virtue. Personal struggles were kept within the private sphere, and intimate disclosures were typically reserved for those closest to us. However, in today’s cultural climate—especially among Gen Z and millennials—there is a much greater emphasis on emotional transparency. Conversations around mental health, trauma, and personal growth are normalised, and platforms like Instagram, TikTok, or Reddit have made it routine to disclose vulnerable experiences publicly.

This shift raises essential questions about the validity of older theories, like Social Penetration Theory, which assumes that self-disclosure develops gradually and reciprocally as intimacy deepens. In modern contexts, this pattern is often disrupted. People might share deeply personal experiences with acquaintances, online audiences, or even strangers—sometimes before any real intimacy has formed. In these cases, disclosure may not function as a trust-building exercise but rather as a performance, a therapeutic outlet, or a way to gain validation and connection in a world where public vulnerability is celebrated.

Additionally, one-sided or non-reciprocal disclosure—particularly online—challenges the theory’s assumption that self-disclosure always occurs in balanced exchanges. "Trauma dumping," for instance, or sharing deeply emotional content without an invitation or emotional exchange, may serve different purposes, such as venting or soliciting support, rather than fostering closeness in a dyadic relationship.

These changing norms suggest that self-disclosure is not only relational but also cultural and generational. As a result, foundational research—much of it conducted in the mid-to-late 20th century—may no longer reflect how disclosure functions in modern romantic relationships. This points to a broader issue in relationship psychology: the risk of treating historically contingent behaviour as timeless.

Finally, while increased openness has many benefits—such as reducing stigma and encouraging emotional honesty—it can also lead to social fatigue, blurred boundaries, or feelings of pressure to be vulnerable before one is ready. When disclosure becomes an expectation rather than a choice, its authenticity and effectiveness as a relational tool may be undermined.

In short, the meaning, purpose, and process of self-disclosure are fluid. They shift with the cultural moment, making it essential for theories like Social Penetration to be re-evaluated within a contemporary framework.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN SELF-DISCLOSURE

Self-disclosure theory often assumes that individuals progress through disclosure at a relatively predictable pace as trust builds. However, this overlooks significant individual variation in how, when, and why people share personal information. Personality, attachment style, neurodiversity, lifestyle, and life experience all shape disclosure habits, challenging the idea that more disclosure always leads to greater intimacy.

Personality traits are a key influence. Extroverts tend to disclose more frequently and quickly, especially in social situations, using verbal sharing to bond. Introverts, by contrast, may find frequent disclosure emotionally taxing. This doesn’t mean they form weaker relationships—introverts may share less often but with greater depth and sincerity. Relationship satisfaction, therefore, may depend more on emotional quality than on the quantity of disclosure.

Attachment style also plays a role. People with an avoidant attachment may be less comfortable with deep emotional disclosure yet maintain long-term, committed relationships. Conversely, those with an anxious attachment may disclose too quickly or intensely, seeking reassurance but sometimes overwhelming their partner. These differences suggest healthy intimacy does not always require symmetrical or frequent disclosure.

Neurodiversity complicates things further. For example, some autistic individuals may either avoid disclosure due to communication barriers or disclose highly personal information without following typical social pacing. These patterns may not align with traditional ideas of how disclosure "should" unfold, highlighting the need to reassess how intimacy is defined and measured across different populations.

Lifestyle and external factors can also influence disclosure. Substances like cannabis, for instance, have been linked to both increased openness and emotional dampening, depending on context and frequency of use. Some individuals may become more expressive, while others disengage emotionally. These variations further demonstrate that self-disclosure is not a fixed trait but a dynamic process shaped by context and state of mind.

Importantly, not everyone has something "deep" to disclose. Some people live relatively stable, trauma-free lives and may not possess a store of emotionally significant content to reveal. Their relationships may thrive on emotional honesty and mutual understanding rather than confessions or revelations. This challenges the assumption—implicit in theories like Social Penetration—that all people possess layers of hidden content that must be peeled back over time.

Ultimately, this raises a key critique: Is intimacy about revealing secrets—or simply feeling seen and understood? Some couples build closeness through similarity, shared values, or wordless connection, not through extensive disclosure. Others require active verbal sharing to feel secure. Therefore, the theory's assumption that all relationships follow the same disclosure pathway is overly narrow.

In light of this, self-disclosure theory risks becoming too rigid or prescriptive, failing to account for the complexity of human variation. Future models of intimacy would benefit from incorporating a more flexible, person-centred approach that reflects how different people connect—verbally, emotionally, or even non-verbally.

SELF-DISCLOSURE CAN SOMETIMES DAMAGE RELATIONSHIPS

Social Penetration Theory (SPT) presents self-disclosure as a gradual, reciprocal process that deepens intimacy. However, this linear and idealised model does not fully account for situations where self-disclosure may have negative or unintended consequences.

One major criticism is that SPT assumes disclosure will naturally lead to closeness when, in reality, the outcome of disclosure depends heavily on timing, mutual readiness, and content. Sharing too much personal or emotionally intense information early in a relationship—known as premature disclosure—can have the opposite effect of what the theory predicts. Rather than fostering intimacy, it may overwhelm or alienate a partner, mainly when trust has not yet been established. This challenges the theory's assumption that disclosure and intimacy rise in tandem.

Similarly, SPT overlooks the issue of asymmetrical disclosure, where one partner reveals significantly more than the other. Rather than reinforcing emotional reciprocity, such imbalance can create discomfort or pressure, disrupting the mutual progression the theory describes. It assumes a level of synchrony in relational development that does not always reflect real-life experience.

Moreover, SPT treats disclosure as inherently beneficial, yet not all self-disclosures are constructive. Disclosure of trauma, deep insecurities, or personal regrets—mainly when excessive or poorly timed—can place an emotional burden on the listener or provoke unintended reactions, such as pity, discomfort, or even judgment. In contemporary terms, this is often referred to as “trauma dumping”, where one person offloads distressing information without regard for the emotional impact on the other. In such cases, disclosure may feel more cathartic for the speaker than connective for the recipient.

In addition, pessimistic or self-focused disclosure, where individuals consistently centre conversations around personal problems, insecurities, or unresolved grievances, may erode relational warmth over time. Rather than deepening closeness, repeated negative disclosure can contribute to emotional fatigue or relational imbalance—especially if it is not met with mutual openness or emotional responsiveness.

Finally, SPT offers little clarity on how much disclosure is appropriate or at what stage. How “deep” is deep enough? At what point does emotional honesty become emotional overload? The theory leaves these questions unanswered, implying a uniform progression without considering the nuanced, sometimes nonlinear paths relationships can take. It also does not clearly distinguish between disclosure that builds trust and disclosure that inadvertently tests, threatens, or destabilises it.

CULTURAL LIMITATIONS OF SOCIAL PENETRATION THEORY

One of the key criticisms of Social Penetration Theory (SPT) is its assumption that verbal self-disclosure is the universal pathway to emotional intimacy. Developed within a Western, individualistic context, SPT reflects cultural values emphasising openness, autonomy, and emotional transparency. Within this framework, intimacy is seen as something that unfolds through the gradual exchange of personal information—what Altman and Taylor described as “peeling back layers” to reach deeper levels of the self.

However, this assumption does not necessarily apply across cultures. In collectivist societies, such as those in East Asia, the Middle East, or parts of Africa and Latin America, values like harmony, indirect communication, and family obligation often precede personal disclosure. Maintaining social cohesion and avoiding embarrassment or shame in these cultures can mean that emotional restraint is more appropriate than verbal openness. As a result, low levels of self-disclosure do not necessarily indicate low intimacy—relationships may be very close but expressed through non-verbal acts of care, loyalty, or shared duty rather than spoken vulnerability.

SPT also does not adequately account for cultural scripts around modesty, privacy, and emotional control, which shape how much people disclose and when and to whom. For example, individuals raised in traditional or religious communities may be socialised to avoid discussing personal feelings, trauma, or relationships, even with close partners. The idea that intimacy naturally grows through increasingly deeper disclosure may not reflect lived relational experience in these contexts.

Furthermore, in many cultures, emotional intimacy is earned over long periods through shared experiences, not necessarily by revealing private information early on. SPT’s intimacy model may, therefore, appear too rapid, individualised, or emotionally explicit for certain cultural norms. The theory does not address these alternate relational timelines or styles.

This raises concerns about SPT's ethnocentrism—it reflects the norms of the culture in which it was developed but may not translate well across the globe. While self-disclosure might be a reliable predictor of relationship development in the West, its role and interpretation vary significantly elsewhere. As such, applying SPT universally risks imposing Western ideals of openness and directness onto cultures that value subtlety, restraint, or communal responsibility over personal expression.

In summary, SPT’s emphasis on verbal, reciprocal disclosure as the core mechanism of intimacy may not hold in all cultural contexts. A more culturally sensitive approach would recognise that intimacy is not one-size-fits-all and that different societies foster closeness through verbal, experiential, behavioural, or symbolic means.

THE ROLE OF SELF-DISCLOSURE IN RELATIONSHIPS

According to social penetration theory, romantic relationships develop as partners engage in more profound and broader self-disclosures. When individuals share personal thoughts, emotions, and experiences over time, intimacy and trust strengthen, reinforcing relationship satisfaction.

However, the onion metaphor used in this theory also suggests that self-disclosure decreases when relationships deteriorate. As conflicts arise or emotional distance grows, partners may start withholding personal thoughts and feelings, creating barriers to intimacy. This withdrawal can contribute to further emotional detachment, making relationship repair increasingly tricky.

Other theories of relationship breakdown, such as Duck’s Phase Model, highlight that couples often engage in intense discussions and negotiation efforts when their relationship is in jeopardy. These discussions typically involve deep emotional self-disclosures, where partners express frustrations, doubts, or unspoken concerns to restore closeness or redefine the relationship.

Interestingly, while self-disclosure is generally beneficial, in some cases, excessive disclosure during conflict can intensify tensions rather than resolve them. Discussions focusing too much on past grievances or emotional dissatisfaction might reinforce negativity rather than rebuild trust. This suggests that self-disclosure alone does not guarantee relationship success—it must be constructive, reciprocal, and occur in a supportive environment.

Does the onion metaphor fully explain these patterns of self-disclosure in relationships? Are there limitations to this model, and could a more flexible approach better describe how self-disclosure changes over time?

THE CHANGING ROLE OF SELF-DISCLOSURE ACROSS RELATIONSHIP STAGES

Social Penetration Theory (SPT) suggests that romantic relationships develop and deepen through reciprocal, layered self-disclosure. As individuals share personal thoughts, emotions, and experiences, intimacy and trust build—reinforcing emotional closeness and relationship satisfaction. In this model, self-disclosure is the vehicle through which partners move from superficial to profound emotional connection.

However, the same “onion metaphor” that symbolises emotional depth in SPT also implies that the process can reverse. When relationships begin to deteriorate, self-disclosure may decrease, not just in frequency but in-depth and authenticity. As conflicts emerge or emotional distance grows, partners may withdraw, becoming less open and emotionally available. This creates a feedback loop: reduced disclosure leads to greater distance, making further disclosure less likely. Intimacy erodes not through active conflict alone but through the gradual silence of withheld vulnerability.

Yet, not all forms of disclosure during relationship strain are helpful. Duck’s Phase Model of relationship breakdown notes that couples often engage in intensified communication as the relationship nears its end. This may be emotional confrontations, “clear-the-air” conversations, or efforts to renegotiate the relationship. These disclosures are not necessarily bonding moments; they often emerge from frustration, disillusionment, or a desire for closure rather than connection.

In these cases, emotional self-disclosure during conflict may not foster closeness but exacerbate tensions. Repeated focus on unresolved grievances, past mistakes, or unmet emotional needs can deepen hurt rather than heal it. What matters is that disclosure happens and how, when, and why it occurs. If disclosure is one-sided, emotionally charged, or lacking in empathy, it may serve more as a cathartic release than a mutual pathway to understanding.

This introduces a limitation in SPT’s framework. While the theory offers a compelling model of how intimacy builds, it does not fully account for disclosure's volatile, strategic, or destructive nature in times of relational distress. SPT frames self-disclosure as a generally linear and positive force—but relationships are rarely linear, and not all sharing is healing.

Moreover, disclosure does not always recede in a neat reversal of growth. Some individuals may disclose more as a relationship falters—not to build closeness but to assert blame, demand validation, or test emotional responses. Others may shut down altogether, replacing words with avoidance. These behaviours suggest that the “onion” metaphor may be too rigid to capture the complex, dynamic, and sometimes chaotic communication patterns in deteriorating relationships.

A more nuanced understanding would acknowledge that the meaning and impact of disclosure change across relational contexts. In the early stages, disclosure signals openness and trust. In later stages, it can be a means of repair—or rupture. The exact words, shared in a different emotional climate, can either draw partners closer or push them further apart.

In conclusion, while Social Penetration Theory captures the early growth of intimacy well, it does not sufficiently explain how disclosure functions during relational decline or repair. A more flexible model would account for the motivations, timing, and emotional tone behind disclosure—recognising that what draws people together in one moment may drive them apart in another.

.

APPLY IT:

SCENARIO

After ten years of marriage, Daniel and Sophia realised that their busy schedules were causing them to drift apart. Sophia, a surgeon, often worked long hours, while Daniel, a freelance writer, spent most of his time at home. Although they loved each other, their conversations had become transactional—focused on household responsibilities rather than their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

Determined to reconnect, they introduced a weekly self-disclosure night. Every Sunday evening, they sat together with no distractions—no phones, no television—and took turns sharing their week, emotions, and personal struggles or victories.

Daniel shared the challenges of working alone, his excitement about a new writing project, and his frustrations with creative blocks. Sophia opened up about the emotional toll of working in a high-pressure hospital environment, the cases that stuck with her, and her fears about balancing her career and family life.

Over time, this intentional self-disclosure strengthened their emotional connection. They began to understand each other’s stressors, appreciate each other’s efforts, and anticipate each other’s needs more effectively. As a result, their marriage felt more profound, more supportive, and more fulfilling.

QUESTIONS:

Explain how research into self-disclosure supports Daniel and Sophia’s satisfying relationship experience.

What sort of things would you disclose to strengthen emotional intimacy?

Why do you think self-disclosure needs to be a two-way process to be effective?