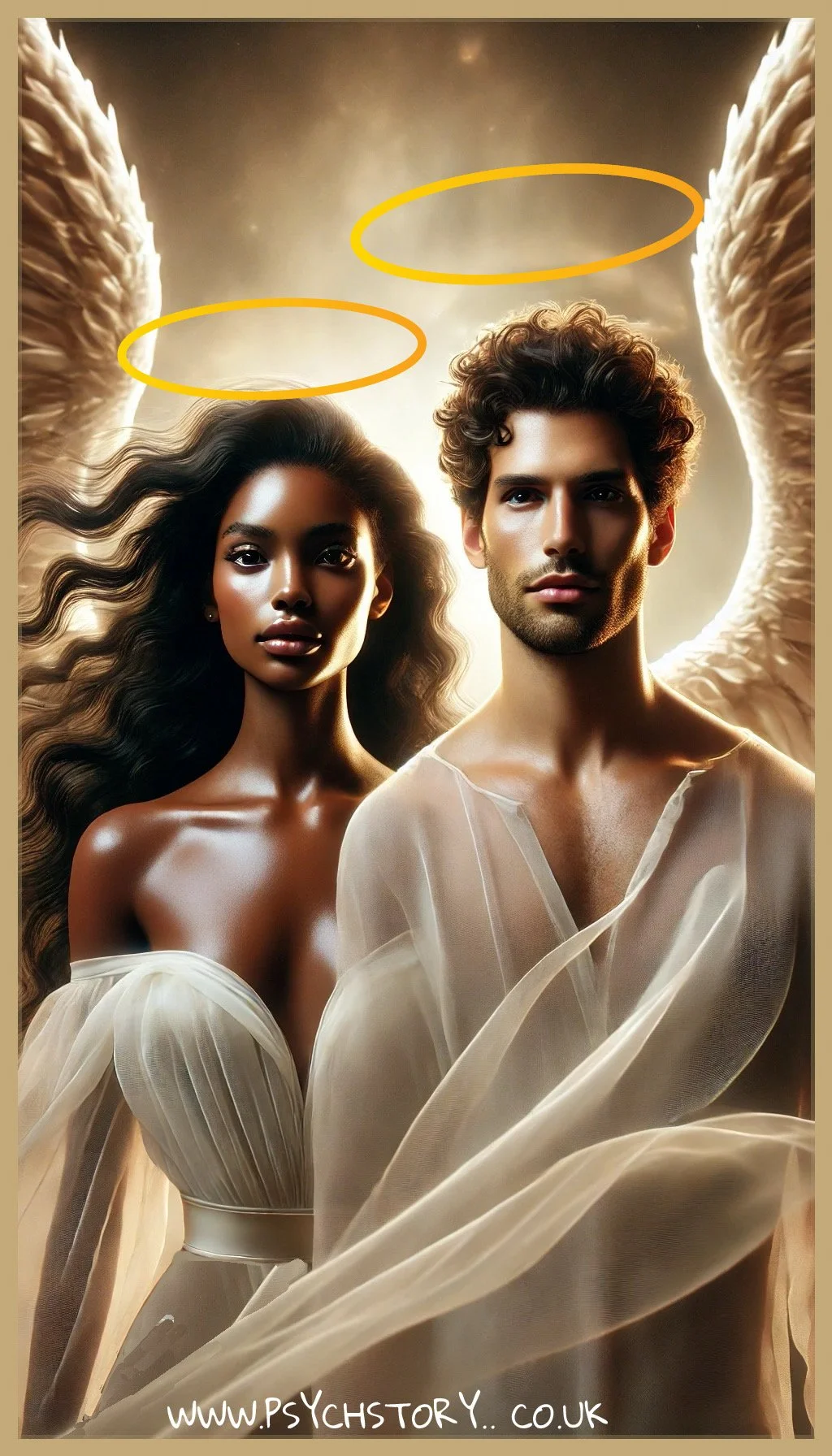

THE HALO EFFECT

THE HALO EFFECT

DEFINITION AND ORIGIN

The halo effect is a cognitive bias in which one positive characteristic—most often physical attractiveness—leads us to assume a person has other unrelated positive traits, such as intelligence, kindness, confidence, sociability, and success. This mental shortcut causes us to make quick, often unconscious, judgements based on appearance alone.

The term was first introduced by Edward Thorndike in 1920, who found that military officers rated soldiers more favourably across multiple traits if they had a good impression of just one quality.

In the context of romantic attraction, the halo effect plays a major role in how we form first impressions. When someone is physically attractive, we believe they must also be a better person overall. For example, someone might assume an attractive person is more fun, trustworthy, or emotionally stable—even before speaking to them. This bias can make appearance seem more critical than it is, and can lead people to overlook deeper compatibility issues in favour of surface-level traits

This bias can cause distorted judgment in various contexts, including personal relationships, business, marketing, education, and the legal system. A classic example of the halo effect occurs when someone perceives a physically attractive person as more intelligent, competent, and trustworthy, even without any evidence for these qualities.

HOW THE HALO EFFECT WORKS

The halo effect operates through a mental shortcut: People fill in missing information about an individual or entity based on a single known trait. This simplifies decision-making but often leads to errors in judgment. It is an unconscious bias in which one positive characteristic, such as attractiveness or charisma, shapes a person's perception of various unrelated traits.

FOR EXAMPLE:

If someone sees a well-dressed, physically attractive individual, they may assume that the person is intelligent, kind, and successful.

Conversely, if someone looks dishevelled or unkempt, they might be perceived as lazy or untrustworthy, even if such assumptions are unfounded.

This mental shortcut reflects an individual’s preferences, prejudices, ideology, and social perception, making the halo effect a powerful yet often inaccurate tool in human judgment.

SUPPORTING RESEARCH

The halo effect helps explain initial attraction in personal relationships. People often assume that someone physically attractive also possesses deeper positive qualities, such as warmth, trustworthiness, or emotional intelligence.

DION, BERSCHEID, AND WALSTER (1972) – ORIGINAL STUDY ON THE HALO EFFECT

AIM

To investigate whether physical attractiveness influences perceptions of personality traits and social competence.

PROCEDURE

Participants were shown photographs of three individuals (strangers) and asked to rate them across various categories, including personality traits such as happiness, career success, and intelligence.

The ratings were compared to an attractiveness rating assigned to each photograph based on evaluations from 100 students.

FINDINGS

Individuals rated as more physically attractive were also perceived as possessing more positive traits, including higher intelligence, greater social competence, and increased overall happiness.

The less attractive individuals were rated lower on these positive characteristics despite no factual basis for this judgement.

CONCLUSION

The study provided strong evidence for the halo effect, demonstrating that people unconsciously attribute positive personality traits to individuals based solely on their physical appearance.

This cognitive bias suggests that attractiveness can influence social perception, potentially affecting job recruitment, legal judgments, and romantic attraction.

FEINGOLD (1988) – META-ANALYSIS OF THE HALO EFFECT IN RELATIONSHIPS

Feingold conducted a meta-analysis of 17 studies examining the link between attractiveness and perceived personality traits in real-life relationships. He found that the halo effect persisted across various settings, reinforcing that physical appearance significantly influences how people are evaluated in personal and professional interactions.

This bias has been widely observed across various settings:

Research suggests that teachers may assume attractive students are more capable in education, leading to inflated grades and favourable treatment, even when academic performance is equal.

In the workplace, attractive applicants are more likely to be hired or promoted, as they are perceived as more competent and socially skilled.

Studies in legal contexts show that attractive defendants often receive lighter sentences, while less attractive individuals are judged more harshly (Efran, 1974).

LANDY AND ARONSON (1969) – THE HALO EFFECT IN A LEGAL CONTEXT

Landy and Aronson found that attractiveness affects legal outcomes, particularly in criminal trials. Their study showed that more attractive victims led to harsher punishments for defendants, whereas attractive defendants were treated more leniently by mock jurors. This suggests that the halo effect extends beyond social and romantic contexts, influencing legal judgments and moral perceptions.In marketing, attractive celebrities and sleek branding create positive associations that lead consumers to assume higher-quality products.

These findings have important implications. The halo effect distorts social perception and can lead to unfair advantages in real-life situations. In relationships, it may lead to idealisation, where negative traits are ignored due to someone's appearance. In legal and professional settings can result in systemic bias, with judgments based more on looks than on evidence or competence. This highlights how much social judgement is shaped by unconscious bias, undermining fairness and objectivity.

THE HORN EFFECT – THE OPPOSITE OF THE HALO EFFECT

The horn effect is the negative counterpart to the halo effect. While the halo effect causes individuals to overestimate someone's positive traits, the horn effect leads people to assume negative qualities based on a single undesirable characteristic.

FOR EXAMPLE:

People with messy hair and poor posture may be perceived as lazy or incompetent, even if they are highly skilled.

If a company releases a single flawed product, consumers may lose trust in the entire brand, even if their other products are high quality.

Both the halo and horn effects demonstrate how cognitive biases shape our perceptions, leading us to make snap judgments rather than evaluating situations objectively.

CRITICISMS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE HALO EFFECT

HORN EFFECT — THE NEGATIVE HALO

While the halo effect explains how one positive trait can influence the overall perception of a person, it does not account for the reverse phenomenon: the horn effect. This occurs when a single negative characteristic—such as unattractiveness, poor hygiene, or social awkwardness—leads to broad negative assumptions about a person’s intelligence, competence, or moral character. For example, an individual judged as physically unattractive might unfairly be assumed to be lazy or less socially capable. The existence of the horn effect challenges the completeness of the halo effect as a theory of impression formation, suggesting it may be just one part of a wider pattern of trait-based cognitive bias. While the halo effect focuses on positive distortions, true social perception likely involves a spectrum of biased judgements, both positive and negative.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

Not everyone is equally susceptible to the halo effect. Some individuals make more objective assessments. People vary in their importance on appearance; not all individuals are equally affected.

SITUATIONAL FACTORS The halo effect is not absolute and can be overridden by substantial evidence. For instance, if a beautiful individual is repeatedly caught cheating or lying, their positive image may eventually be reversed.

SCIENTIFIC LIMITATIONS

A key issue with evaluating the halo effect—particularly in the context of attraction—is the difficulty of studying it scientifically. Because attraction involves a complex mix of personal preferences, cultural influences, and emotional reactions, it is nearly impossible to isolate variables in a controlled way. Most research into the halo effect relies on correlational data or questionnaires using photographs (e.g. Dion et al., 1972). While these methods can demonstrate general trends, they cannot establish causality or accurately reflect real-world interactions, where personality, context, and behaviour also shape impressions. Additionally, questionnaire-based studies are subject to demand characteristics and social desirability bias—participants may not accurately report how much appearance influences their judgements, especially in areas like dating. These methodological constraints make it difficult to thoroughly test the halo effect in naturalistic romantic settings, meaning conclusions must be drawn cautiously.

Many studies rely on artificial and oversimplified stimuli, such as static photographs or profile descriptions. These don’t capture the dynamic nature of real-life interactions, where people form impressions based on voice, behaviour, humour, and emotional responses—not just looks. For example, someone attractive in a photo might seem arrogant or dull in conversation, but static images fail to capture this. This reliance on visual-only data may overstate the strength of the halo effect, particularly in attraction. Future research would benefit from using multi-sensory or behavioural data, including longitudinal observations of real interactions, to assess how and when the halo effect emerges or fades over time.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES?

Although individual and cultural differences exist in how attractiveness is defined, Anderson et al. (1992) found that higher body weight is associated with health and attractiveness in some non-Western cultures where food is scarce. In contrast, in many Western cultures, thinness is ideal. Despite these differences in preference, this does not mean physical appearance is irrelevant to romantic attraction. Langlois et al. (2000) conducted a meta-analysis. They found that facial attractiveness is consistently valued across cultures, suggesting that physical appearance remains an essential factor globally. There is no known culture where physical attractiveness is completely unvalued. While different societies may favour different traits—such as body size, skin tone, or grooming—some form of aesthetic preference appears to exist universally. This implies that while the specific traits considered attractive may vary, the halo effect and other appearance-based biases remain relevant. By local standards, attractive individuals are still more likely to be judged positively in unrelated areas, such as intelligence or sociability. Therefore, cultural variation in beauty standards does not invalidate the role of physical attractiveness in attraction but instead supports the idea that the bias toward attractive people is culturally widespread, even if what counts as “attractive” changes.

LONG-TERM RELATIONSHIPS AND THE HALO EFFECT

While the halo effect can strongly influence initial attraction, its relevance may decrease as individuals build deeper relationships. First impressions, primarily based on appearance, may create an early bias, but as people get to know each other, personal traits, behaviours, and shared experiences become more important. Research suggests that initial stereotypes based on appearance can fade once interpersonal knowledge increases, particularly in close relationships, where deeper compatibility becomes the focus (Sprecher & Regan, 2002). In long-term romantic relationships, the novelty of physical attractiveness may diminish—a phenomenon sometimes described in behavioural economics as diminishing returns, where repeated exposure to the same stimulus leads to reduced emotional impact. While looks may initially carry significant weight, they often become less central as emotional intimacy, personality, and commitment take precedence. However, the process can sometimes be reversed. When a partner’s appearance changes over time—such as weight gain, ageing, or reduced grooming—this may activate a horn effect, the opposite of the halo effect. Negative changes in physical appearance can be unfairly linked to traits like laziness, selfishness, or a lack of self-control, even when such assumptions are unfounded. In some cases, perceived physical decline is cited in relationship dissatisfaction or breakups, mainly

if one partner interprets it as a sign of emotional withdrawal or reduced effort in the relationship. This suggests that while the halo effect plays a decisive role in the early stages of attraction, its influence on relationship maintenance is more complex. Physical appearance can remain symbolically important, especially when tied to respect, care, or effort—but it is rarely the sole factor in long-term relationship success. As relationships deepen, psychological and emotional compatibility override early appearance-based judgements, although traces of the halo and horn effects can still shape ongoing perception.

IS THE HALO EFFECT EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY IN DIGUISE?

The halo effect is generally described as a cognitive bias, suggesting it is learned through nurture—a mental shortcut developed from social experiences, media exposure, and cultural values that lead people to generalise positive traits from appearance. However, it can be argued that the halo effect may have biological roots, particularly in the context of attraction. From an evolutionary perspective, humans may be predisposed to favour those who display cues of genetic fitness, such as facial symmetry, clear skin, and youth—traits often judged as physically attractive. In this sense, people's optimistic assumptions about attractive individuals could reflect an evolved tendency to associate beauty with health and reproductive value.

Physical attractiveness often signals health and reproductive fitness, which would have conferred survival advantages in ancestral environments. For example, facial symmetry is attractive across many cultures because it indicates developmental stability. A symmetrical face is less likely to have been affected by illness or genetic disruption during early development, making it a potential marker of good genes (Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999).

This preference for health-related traits extends beyond humans. In the animal kingdom, many mammals use visual or olfactory cues, such as scent, to assess genetic compatibility or hormonal health in potential mates. These behaviours suggest that judging based on physical or sensory traits is not uniquely human but an evolutionarily widespread strategy for selecting high-quality partners. While some individuals—such as those who are blind or neurodivergent—may place less emphasis on appearance, they typically rely on alternative cues such as voice, scent, or emotional expression. In these cases, attraction involves interpreting personality, compatibility, or fitness signals. Thus, although beauty standards vary between individuals and cultures, the underlying tendency to evaluate potential partners based on perceivable indicators of mate quality appears to be a universal aspect of human—and animal—mating behaviour.

BETA BIASED THEORY

Although the halo effect is observed across individuals, most descriptions of the theory assume it operates equally across genders. This reflects a form of beta bias—minimising or ignoring real sex differences in how attraction is processed. However, research suggests that men may be more susceptible to the halo effect in the context of physical attraction, likely due to evolved mate selection strategies.

For example, Buss (1989) found that men significantly emphasise physical attractiveness when choosing partners, as it signals fertility and reproductive health. Sigall and Landy (1973) demonstrated that male participants rated an essay as more intelligent and persuasive when paired with a photo of an attractive woman, indicating that men more readily generalise from physical beauty to unrelated traits.

Similarly, Agthe, Spörrle & Maner (2010) found that attractiveness triggered more substantial halo effects in men, particularly when judging women. Their findings suggest that the halo effect may not be a neutral bias but one shaped by evolutionary pressures that differ between sexes.

This questions the gender-neutral framing of the halo effect in much of the literature. If the effect is more pronounced in men—at least in attraction contexts—then the theory should reflect these biological and psychological differences rather than downplay them. By assuming the halo effect applies equally, the theory may be beta-biased. It would benefit from incorporating a more alpha-biased perspective that recognises sex-specific mechanisms in mate evaluation.

THEORETICAL INTEGRATION — LINKS TO OTHER THEORIES OF ATTRACTION

The halo effect may also interact with or challenge other established theories of romantic attraction. For example, the Matching Hypothesis (Walster et al., 1966) suggests that people are more likely to form relationships with others who are similarly attractive to themselves. However, suppose the halo effect causes people to overestimate the personality traits of attractive individuals. In that case, it raises the question of why people would "match down" if the attractive partner is perceived as better in every way. This contradiction suggests that the halo effect may override matching behaviours, especially in early-stage attraction, or that people may misjudge their attractiveness due to bias. Additionally, the halo effect may strengthen the predictions of the Reward/Need Satisfaction Theory, as it may inflate the perceived emotional and social rewards of being with an attractive partner, thus reinforcing attraction on a subconscious level.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS — REAL-WORLD RELEVANCE

Understanding the halo effect has important implications beyond personal relationships. In the workplace, attractive job candidates may be more likely to be hired or promoted, even when equally qualified peers are overlooked. In the legal system, research such as Efran (1974) has shown that attractive defendants often receive more lenient sentences, while unattractive ones are judged more harshly. Teachers may unconsciously give higher marks or more positive behaviour ratings to physically attractive students in education. Recognising the halo effect can inform efforts to reduce appearance-based bias through blind recruitment processes, structured interviews, and bias-awareness training. Understanding how appearance distorts perception in dating platforms could also promote more authentic, compatibility-based matching systems.

DEVELOPMENTAL DIFFERENCES — AGE AND LIFE STAGE

The influence of the halo effect may also vary depending on a person's age and developmental stage. Younger individuals, particularly adolescents and emerging adults, may emphasise appearance-based cues, making them more susceptible to the halo effect in early romantic attraction. Older individuals, by contrast, may prioritise emotional compatibility, shared values, and life goals over appearance, which reduces the impact of superficial judgements. This developmental shift suggests that the halo effect is not static but contextual and age-sensitive. As people gain life experience, their attraction preferences and evaluative strategies may become more balanced and less influenced by appearance alone. This challenges the universality of the halo effect across the lifespan and supports the view that its strength can change over time.

CONCLUSION

The halo effect is a well-documented cognitive bias that plays a decisive role in romantic attraction, shaping how individuals assess others based on appearance. While traditionally viewed as a social perception error, growing evidence suggests that it may also reflect evolutionary heuristics for identifying healthy and genetically fit mates. Despite its strong influence in early-stage attraction, its role in long-term relationships is more complex and may fade or reverse over time. There are also significant limitations in researching the halo effect scientifically due to the ethical and practical challenges of experimentally manipulating attraction and social judgement. Most findings come from artificial or correlational methods, limiting the ecological validity of conclusions. Nonetheless, understanding the halo effect remains crucial. Awareness of this bias can help people and institutions recognise and challenge automatic assumptions, reducing unfair advantages based on appearance and encouraging more accurate, thoughtful judgement in both personal and professional domains.