RHYTHMS: CIRCADIAN, INFRADIAN AND ULTRADIAN

CHRONOBIOLOGY

Chronobiology is the scientific study of biological rhythms.

More precisely:

Chronobiology examines how living organisms organise behaviour, physiology and internal processes according to daily (circadian), shorter (ultradian), and longer (infradian) cycles, and how these rhythms are generated and synchronised with the environment.

Core areas include:

• Circadian rhythms (about 24 hours)

• Ultradian rhythms (shorter cycles, e.g., sleep stages)

• Infradian rhythms (longer cycles, e.g., menstruation)

• Seasonal rhythms (e.g., migration, hibernation)

• Biological clocks (SCN, peripheral clocks)

• Zeitgebers (environmental cues like light or temperature)

• Entrainment (how internal rhythms align with the environment)

It bridges neuroscience, endocrinology, genetics, physiology and behaviour.

In plain terms:

Chronobiology studies how the body keeps time—and what happens when its internal clocks drift, misalign or are disrupted

WHY CHRONOBIOLOGY MATTERS IN PSYCHOLOGY

Chronobiology explains real-world phenomena such as shift-work disorder, jet lag, seasonal affective disorder (SAD), teenage sleep-phase delay, and the timing of medication (chronotherapy). Questions on “applications”, “issues and debates” (nature–nurture, reductionism), and “research methods” (e.g., actigraphy, constant routines) frequently draw on chronobiology.

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

SPECIFICATION: Biological rhythms: circadian, infradian, and ultradian, and the differences between these rhythms. The effect of endogenous pacemakers and exogenous zeitgebers on the sleep/wake cycle

The specification outlines several requirements for this topic.

Students are expected to:

Describe and identify the three primary biological rhythms—circadian, ultradian and infradian

Apply this knowledge when explaining aspects of behaviour.

Understand the roles of endogenous pacemakers and exogenous zeitgebers.

Explain how these internal and external factors regulate biological timing.

Beyond description, students are required to evaluate these mechanisms by assessing the quality of the supporting evidence, identifying methodological weaknesses in the research, and assessing how effectively each mechanism accounts for human behaviour.

Although this content appears toward the end of the specification, it is conceptually extensive because it integrates multiple components: biological rhythms, internal timing systems and environmental cues. Many evaluation points and research studies can be applied across different parts of the topic, which makes the material more coherent once the underlying processes are understood. A firm grasp of how each rhythm and regulatory system functions is essential before advanced discussion and evaluation can be carried out effectively

KEY TERMS – BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS (ALPHABETICAL ORDER)

ROOT TERMS FOR BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS

Circa = about

Diem = day

Ultra = beyond (more frequent than once per day)

Infra = below (less frequent than once per day)

Annus = year

Zeit is German for “time.”

(From Zeit = time.)Geber means “giver.”

Zeitgeber literally means: “time giver” → something that gives the organism its timing cue. Any external cue—e.g., light—that resets and synchronises the body’s internal biological clock.

Pacemaker =A mechanism that generates and regulates rhythmic activity; in humans, it refers to internal clocks, such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), that control circadian rhythms.

Endogenous: Originating within the body; describes internal biological mechanisms that regulate rhythms independently of external cues.

Exogenous: Originating outside the body; refers to environmental or external factors that influence and reset internal biological clocks.

Exogenous Zeitgeber =An external time cue that resets internal biological clocks.

Exogenous Pacemaker = An internal biological clock

ADENOSINE

a neurotransmitter that accumulates during wakefulness, increasing sleep pressure; cleared during sleep.AMPLITUDE

The height of a brain wave on an EEG reflects how synchronised neuronal firing is.ANNUS

Latin root meaning “year.”ARAS (ASCENDING RETICULAR ACTIVATING SYSTEM)

brainstem arousal network promoting wakefulness; part of the ultradian sleep–wake cycling mechanism.BIOLOGICAL RHYTHM:

Any repeating pattern of physiological or behavioural activity.BRAIN WAVE

The electrical activity of the brain, measured by EEG, varies by sleep stage and frequency.CHRONO

Greek root meaning “time.”CHRONOBIOLOGY:

The study of biological rhythms and internal timing systems.CHRONOPHARMACOLOGY:

The study of how drug effects vary with the timing of administration.CIRCADIAN RHYTHM

A biological rhythm lasting about 24 hours (e.g., sleep–wake cycle).CIRCA

Latin root meaning “about.”CORTISOL

a hormone peaking in the early morning to promote alertness.DIEM

Latin root meaning “day.”EEG (ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAM)

measures electrical brain activity via scalp electrodes.ENTRAINMENT

The process by which external cues synchronise internal rhythms to the environment.FREE-RUNNING RHYTHM

the natural rhythm expressed without zeitgebers (e.g., constant darkness).HPA AXIS (HYPOTHALAMIC–PITUITARY–ADRENAL)

a system controlling stress responses; influences cortisol and circadian stability.HPO AXIS (HYPOTHALAMIC–PITUITARY–OVARIAN)

regulates the menstrual cycle; it is the endogenous pacemaker for infradian rhythms.INFRA

Latin root meaning “below.”INFRADIAN RHYTHM:

A rhythm lasting longer than 24 hours (e.g., the menstrual cycle).JET LAG

A mismatch between internal circadian timing and local time after travel.LUX

A unit of light intensity.MELATONIN

a hormone released in darkness to promote sleep.NON-24-HOUR SLEEP–WAKE DISORDER

A condition where the circadian clock cannot be reset by light (common in total blindness).PACEMAKER

any internal system generating regular rhythmic activity (SCN, HPO axis, VLPO/brainstem circuits).PERIPHERAL CLOCKS

clock genes found in organs outside the SCN (e.g., liver, heart).PHARMACOKINETICS: The action of drugs on the body and how well they are absorbed and distributed

PHEROMONES

chemical signals that may influence physiology or behaviour in members of the same species; evidence for human menstrual synchrony is weak.PHOTORECEPTORS

Light-sensitive retinal cells that send light information to the SCN.PULSATILE RELEASE PATTERN

Hormones are released in bursts rather than continuously.RAPID EYE MOVEMENT (REM)

a sleep stage characterised by mixed-frequency brain waves and vivid dreaming.REM-ON / REM-OFF NEURONS

Brainstem neurons that switch REM sleep on and off; essential for the ultradian cycling of REM and NREM sleep.ROOT TERMS

Basic conceptual prefixes (circa, diem, ultra, infra, annus).SCN (SUPRACHIASMATIC NUCLEUS)

A cluster of neurons in the hypothalamus that acts as the master circadian pacemaker.SEROTONIN

A neurotransmitter involved in mood and sleep; precursor to melatonin.SHIFT WORK

Misaligned employment patterns can cause fatigue and health issues.SLEEP–WAKE CYCLE

The primary circadian rhythm controls daily patterns of sleep and wakefulness.SYMPATHETIC AROUSAL

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system during stress can disrupt circadian and infradian rhythms.TAU (τ)

The intrinsic length of the free-running circadian period (slightly more than 24 hours in humans).THALAMUS

a relay centre that filters sensory information during sleep, preventing unnecessary arousal.ULTRA

Latin root meaning “beyond.”ULTRADIAN RHYTHM

A rhythm shorter than 24 hours (e.g., the 90-minute sleep cycle).VLPO (VENTROLATERAL PREOPTIC NUCLEUS)

a hypothalamic region that promotes sleep by inhibiting arousal systems; part of the ultradian pacemaker network.

BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS

IN SHORT

Biological rhythms are biological processes that exhibit cyclical variation over time, ranging from hours to years, and reflect the influence of Earth's rotation on us… It's living inhabitants, along with plants and animals.

There are three rhythms we will focus on throughout this module: Circadian, Infradian, and ultradian biological rhythms.

IN MORE DEPTH

Biological rhythms are the body’s natural cycles that organise when various physical and behavioural processes occur. They prevent random events by providing the body with a predictable pattern to follow. These rhythms come from internal systems that keep time and allow essential activities—such as growth, repair, sleep, and hormone release—to occur in the correct order.

These rhythms run over different lengths of time. Some are monthly, such as the menstrual cycle, which follows a repeating pattern of hormonal changes. Others unfold over years, such as puberty, when hormone levels gradually rise, triggering significant physical and emotional changes. Many animals follow yearly rhythms, such as migration or hibernation, that help them survive seasonal changes. There are also very short rhythms: during the night, the NREM–REM sleep cycle repeats in a regular sequence of deep sleep, light sleep, and dreaming. Even the daily sleep–wake pattern shows how the body moves through a familiar cycle of alertness and rest.

Together, these examples show that biological rhythms are real, observable patterns. They help the body stay organised and adapt to the world, rather than functioning as a set of disconnected processes.

NEUROSCIENCE AND ENDOCRINOLOGY

Biological rhythms depend on communication between the brain and the endocrine system. The brain provides the timing mechanism, ensuring that cycles such as sleep, hunger, and alertness occur in a regular pattern. The endocrine system provides chemical control, using hormones to initiate, maintain, and terminate each process. For example, the brain signals the release of melatonin to trigger sleep, cortisol to promote wakefulness, and growth hormone during deep sleep for physical repair. Together, these systems allow the body to regulate its internal timing and maintain stable biological rhythms.

TYPES OF BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS

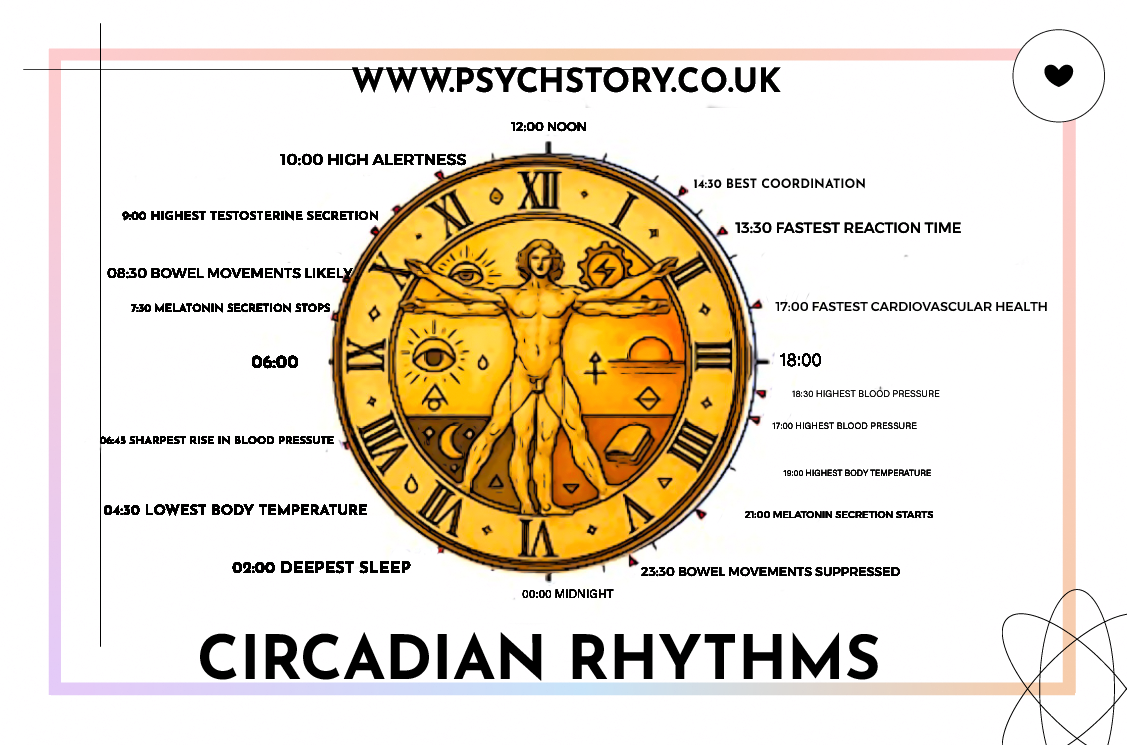

CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS: From Latin circa = about, diem = day. Circadian rhythms are the body’s built-in 24-hour cycles.

EXAMPLES:

Sleep–wake cycle – The daily rhythm of alertness and sleepiness, regulated by the SCN and melatonin. We feel awake in daylight and sleepy at night because the circadian system works on a 24-hour timetable.

Core body temperature cycle – Body temperature rises during the day and falls at night, following a predictable daily pattern that affects alertness, concentration and cognitive performance.

Hormonal rhythms (e.g., cortisol) – Cortisol peaks in the early morning to support wakefulness and gradually declines across the day. This daily rise and fall is a clear circadian pattern.

Patterns of alertness and reaction time – Humans show a daily rhythm in cognitive performance, with faster reaction times in the late afternoon and slower responses during the night, reflecting underlying circadian processes.

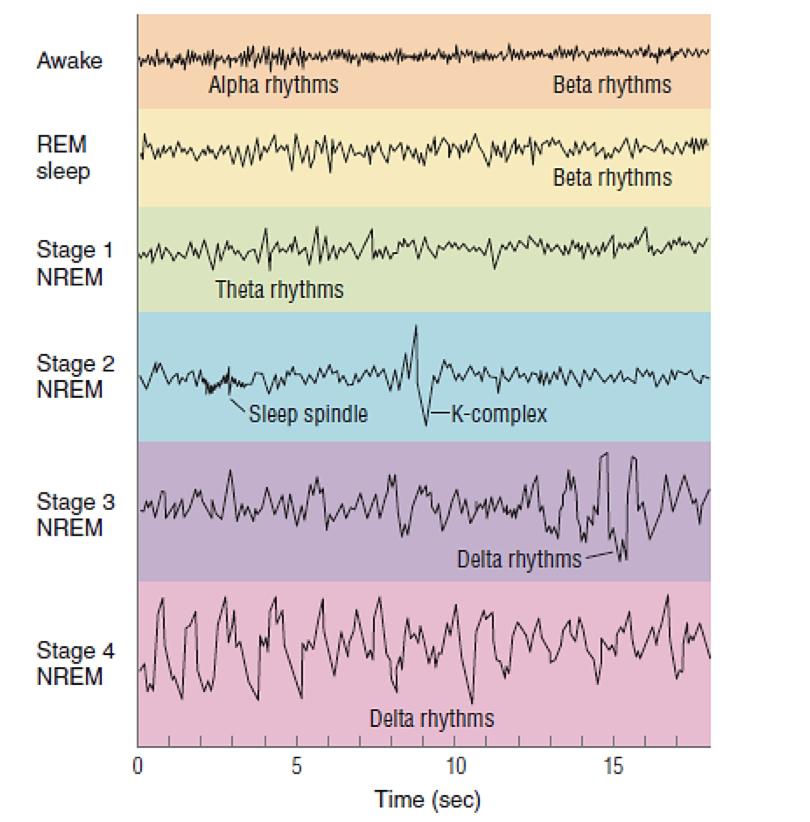

ULTRADIAN RHYTHMS The word ultra means from Latin ultra = beyond, describing rhythms that occur more than once in 24 hours. These are short cycles that repeat several times each day or night, e.g., more than once within 24 hours. They are brief, recurring patterns in physiological and behavioural activity that operate continuously throughout the day and/ or night.

EXAMPLES:

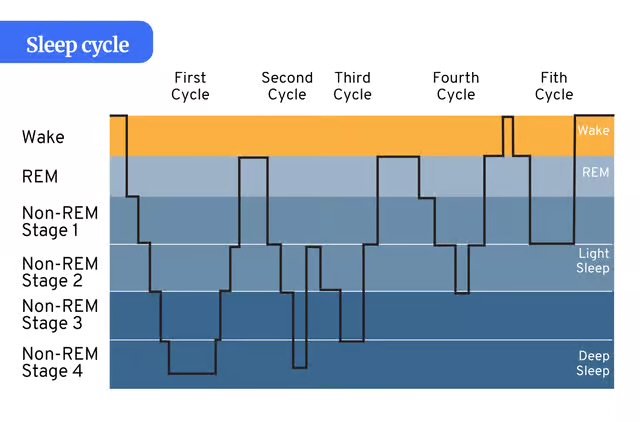

The NREM REM sleep cycle – the 90-minute pattern of NREM and REM sleep repeated multiple times per night.

Heart rate and breathing patterns – continuous, short-term physiological rhythms.

Hormone pulsatility – growth hormone, insulin, and cortisol are released in bursts throughout the day.

Basic Rest–Activity Cycle (BRAC) – 90-minute cycles of alertness and fatigue are observable even during waking hours.

INFRADIAN RHYTHMS: From Latin infra = below) The word infra means “below”, referring to rhythms that occur less frequently than once every 24 hours. They are longer-term cycles extending over days, weeks, or months.

EXAMPLES:

The menstrual cycle – A monthly rhythm in females regulated by hormones that prepares the uterus for pregnancy. Approximately 28 days, controlled by changes in oestrogen and progesterone.

The biannual oestrus cycle – A seasonal reproductive cycle in many mammals, repeating twice per year, and therefore an infradian rhythm because each cycle lasts far longer than twenty-four hours but shorter than a year.

CIRCANNUAL RHYTHMS(from Latin circa = about, annus = year)

These rhythms operate on roughly a yearly cycle, often tied to environmental changes such as daylight length or temperature.

EXAMPLES:

Hibernation – reduced activity and metabolic rate during winter.

Migration – seasonal travel of birds and animals for food or breeding.

Reproductive timing – breeding patterns aligned with favourable conditions.

The annual oestrus cycle (in two categories) – A seasonal reproductive cycle in many mammals, which repeats once per year instead of twice per year or once per month, and is a circannual rhythm because each cycle lasts far longer than twenty-four hours but shorter than a year.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD): A yearly pattern where individuals experience lower mood and energy during the winter months, linked to reduced daylight exposure. Common in winter in the northern hemisphere.

SUMMARY

Ultradian → repeats many times in a day (< 24h)

Circadian → repeats every 24h

Infradian → takes > 24h to repeat (eg, 48h, weekly, monthly, seasonal)

Circannual → roughly 1 year

ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKERS AND EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS

KEY TERMS

PACEMAKER

A mechanism that generates and regulates rhythmic activity; in humans, it refers to internal clocks, such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), that control circadian rhythms.ZEITGEBER

German for “time giver.” Any external cue—exceptionally light—that resets and synchronises the body’s internal biological clockENDOGENOUS

Originating within the body, it describes internal biological mechanisms that regulate rhythms independently of external cues.EXOGENOUS

Originating outside the body, it refers to environmental or external factors that influence and reset internal biological clocks.

ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKERS & EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS – THE CORE OF ALL BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS

All biological rhythms (daily sleep-wake, stages of sleep, menstrual cycle, seasonal changes, etc.) depend on two things working together:

Endogenous pacemakers – these are the internal biological clocks inside us (the main one is the SCN in the brain, plus clocks in almost every organ and cell). They keep our bodies running on roughly 24-hour cycles even when there are no external cues.

Exogenous zeitgebers – these are the external time cues from the environment: light-dark cycle, meal times, exercise, temperature, and social routines. Their job is to grab the internal clocks and adjust them so they match the real world exactly.

Why you absolutely need to know them

Every single thing you will ever be asked about biological rhythms comes back to a straightforward question:

“Are the internal clocks and the external cues properly lined up, or are they out of step?”

Jet lag = cues changed too fast

Shift work = cues flipped upside-down

Teenagers sleeping late = internal clock naturally shifted

Medicine working better at certain times = using cues to hit the clock at the right phase

Get these two ideas straight, and the whole topic suddenly makes perfect sense. That’s why they’re the first (and most important) thing to learn.

ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKERS

Endogenous pacemakers are the body’s internal biological timing systems that generate, maintain and regulate the pattern of biological rhythms. These mechanisms operate within the organism and continue to create rhythmic activity even in the absence of external cues. Each pacemaker controls the timing of a rhythm on its own timescale. For short cycles, such as ultradian rhythms, internal oscillators within the brainstem and autonomic nervous system regulate repeated patterns of activity and rest. For daily rhythms, circadian timing systems set the 24-hour pattern of physiological and behavioural changes. For longer rhythms, such as infradian and circannual cycles, internal hormonal and neural systems organise monthly reproductive patterns or seasonal changes in behaviour and physiology.

Although endogenous pacemakers differ across timescales, they share a fundamental role: they provide a predictable internal structure that organises bodily functions, ensuring that events such as sleep, hormone release, reproduction, and long-term seasonal behaviours occur in a coordinated sequence. These timing systems continue to run in the absence of external information, but their accuracy can drift. This shows that endogenous pacemakers generate the rhythm, while environmental cues are needed to keep it aligned with the outside world.

APPLYING PACEMAKERS TO CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

In circadian rhythms, the primary endogenous pacemaker is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) in the hypothalamus. The SCN generates a roughly 24-hour rhythm that regulates processes such as body temperature, hormone release and the sleep–wake cycle. Even in constant darkness, the SCN continues to produce a near-daily rhythm, demonstrating that circadian timing originates from an internal biological clock.

EXAMPLES OF ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKERS

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM – The sleep-wake cycle. The SCN (suprachiasmatic nucleus) is the internal body clock that generates the 24-hour rhythm.

Pineal gland + melatonin – releases melatonin at night, promoting sleep.

INFRADIAN RHYTHM The menstral Cycle: Hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis – the internal hormonal system that sets the timing of the menstrual cycle.

ULTRADIAN RHYTHM: Brainstem sleep mechanisms (pons, medulla) – generate the 90-minute REM/NREM cycle.

Thalamus – controls NREM rhythms.

CIRCANNUAL RHYTHM: Internal seasonal clock in the hypothalamus – responds to changes in day length and prepares animals for long-term cycles like hibernation.

Melatonin patterns across seasons – more extended melatonin release in winter signals the season.

EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS

DEFINTION

Exogenous zeitgebers are environmental signals that influence the timing of biological rhythms. These cues provide reliable information about changes in the external world, and the body uses this information to adjust internal pacemakers so that biological rhythms stay synchronised with the environment.

They influence all types of rhythms, regardless of timescale. Light and temperature help animals time their circannual behaviours such as hibernation and migration. Social routines, food availability and daily activity patterns influence circadian rhythms such as sleep–wake timing. Mealtimes, stimulation levels and evening habits shape ultradian rhythms such as the progression of REM and NREM sleep. Longer environmental patterns, including seasonal changes, can affect infradian rhythms such as reproductive cycles.

Without exogenous zeitgebers, these rhythms continue because they are generated internally, but they often drift or become poorly aligned with real-world conditions. This misalignment shows that the body relies on exogenous signals not simply as supplementary information but as active mechanisms for entrainment, allowing internal timing systems to remain accurate and adaptive across the different biological timescales.

APPLYING EXOGENOUS ZEITGEIBERS TO CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

In circadian rhythms, the most crucial zeitgeber is light. Light signals detected by the eyes provide daily information about morning and evening, helping the internal circadian pacemaker to stay aligned with the 24-hour day–night cycle. Other cues, such as mealtimes, activity patterns and social routines, also help stabilise the sleep–wake cycle by reinforcing when the body should be alert and when it should rest.

Other important exogenous zeitgebers here include:

Social cues such as mealtimes, work schedules, and social interaction.

Temperature changes, which signal the time of day and influence metabolic rate.

Routine behaviours like exercise or exposure to artificial light.

Without these cues, the body’s internal rhythm can drift, leading to free-running cycles slightly longer or shorter than 24 hours. This shows that exogenous zeitgebers are essential for entrainment—the process of aligning internal biological rhythms with the external world.

EXAMPLE OF EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM:

Light – the primary external cue that resets the SCN each day.

Social routines – mealtimes, activity patterns, work/school times.

Exercise & daily activity – helps stabilise the rhythm.

INFRADIAN RHYTHM:

Pheromones – possible influence when women live closely together.

Stress – can delay or disrupt the cycle.

Nutrition and energy levels – under-eating or sudden weight change can alter cycle timing.

ULTRADIAN RHYTHM:

Cannabis alters REM density and can reduce REM sleep, affecting the pattern of ultradian cycling.

Alcohol disrupts REM in the second half of the night and fragments the 90-minute cycle.

Benzodiazepines – reduce deep NREM sleep and change the structure of REM/NREM cycles.

Caffeine – delays sleep onset and suppresses deep sleep, shifting the timing of ultradian cycles.

Noise and environmental stimulation – interrupt the natural cycling between NREM and REM.

Light before sleep suppresses melatonin and alters the first REM period.

Evening routines and activity levels influence sleep onset and the stability of REM/NREM cycles

CIRCANNUAL RHYTHM:

Day length (photoperiod) – the primary cue signalling winter or summer.

Temperature – falling temperatures cue hibernation behaviour.

Food availability – declining food supply triggers preparation for hibernation.

Identical twins are born in Tromsø, Norway, in 1987. A hospital mix up means they are swapped at birth and raised by completely different families.

Zeit grows up with a Sami reindeer herder far above the Arctic Circle. There is never a clock in the house. The only thing that ever tells him when it should be day or night is natural light. In summer the sun never sets for about two months. There is no night. Zeit can hardly sleep and ends up completely exhausted. In winter the sun never rises for about two months. There is no day. Zeit sleeps sixteen to eighteen hours and can barely stay awake when he finally gets up.

Nate grows up with a retired sea captain who runs everything by one old ship’s clock from the nineteen forties. The clock has never been repaired and now takes exactly twenty six hours to complete one full day. Nate always gets eight perfect hours of sleep, but because he has only ever followed that clock that cannot keep time, his sleeping and waking times shift roughly two hours later every real twenty four hour day, so he eventually tries to milk his cows at three in the morning.

The TV reunion is booked for Saturday eight p.m. Zeit arrives on the right evening, pale and shaking from weeks without a proper night. Nate checks the only clock he has ever known, puts on a suit, and arrives at the studio at two thirty six a.m. on Tuesday morning, wondering where everyone is.

Here is the real point. In real life the sleep wake cycle depends on two forces. The internal body clock sets the rhythm, but like Zeit’s situation it does not run to exactly twenty four hours. It runs slightly long. Every morning natural light gives the correcting cue and drags that longer internal rhythm back to a true twenty four hour day.

We need both: the inner clock that generates the cycle and the daily light that keeps it aligned with the real world. We call this circadian entrainment.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS IN DEPTH

CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS:

CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

(from Latin circa = about, diem = day)

DEFINITION

Circadian rhythms are the body’s built-in 24-hour cycles that keep physical, mental, and emotional processes running in time with the Earth’s day–night pattern. The name comes from circa diem, meaning “about a day.” You can think of them as the body’s internal timetable. This biological clock quietly keeps everything in sync, much like a conductor coordinating an orchestra so that every instrument plays at the right moment.

Each organ and cell in the body contains its own microscopic biological clock. Still, all of them take their cue from one “master clock” in the brain — the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus. The SCN is made up of about 20,000 neurons that keep time through rhythmic electrical activity. Its job is to synchronise all the more miniature clocks in the body so that different systems — such as digestion, temperature regulation, and hormone release — follow the same daily rhythm.

Without this coordination, the body’s internal processes would drift out of sync with one another — a bit like a band with every musician playing to a different beat. You might find your digestive system demanding lunch at 3 a.m. while your sleep system insists on a nap in the supermarket queue. Body temperature might peak when you’re trying to fall asleep, and your alertness levels could hit their high point just as you climb into bed. In short, you’d be permanently jet-lagged without ever leaving your house — the kind of person who could fall asleep anywhere, anytime, except when it’s actually bedtime.

WHAT MAKES A RHYTHM “CIRCADIAN”?

For a biological rhythm to be classed as circadian, it must meet three main conditions:

1. IT MUST BE INTERNAL (ENDOGENOUS)

The rhythm continues even without external cues like light or temperature. For example, if an organism is kept in constant darkness, its body clock still runs on roughly a 24-hour cycle — called the free-running period (symbol τ, “tau”). In humans, this period is usually just over 24 hours. This shows that circadian rhythms arise within the body, not just from responding to the environment.

2. IT MUST BE RESET BY EXTERNAL CUES (ENTRAINABLE)

Although the rhythm is internal, it can be adjusted by zeitgebers (“time givers”) such as light, temperature, or social cues. This keeps the body clock in sync with the real world. For example, when someone flies to another time zone, they experience jet lag until their circadian clock entrains to the new local time.

3. IT MUST BE TEMPERATURE COMPENSATED

The rhythm stays close to 24 hours even when the body or environmental temperature changes. This prevents the body clock from speeding up in the heat or slowing down in the cold. Scientists call this temperature compensation, and they measure it with a value called Q10. If Q10 stays near 1, it means the rhythm keeps good time despite temperature changes.

In short, circadian rhythms are internal, can be reset, and stay stable across temperatures — allowing living organisms to keep accurate time in a changing world.

CIRCADIAN RHYTHM:THE SLEEP-WAKE CYCLE

ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKER FOR THE SLEEP WAKE CYCLE: THE SCN

The SCN keeps this chaos in check by receiving light information from the eyes. Special photoreceptor cells in the retina detect changes in brightness and send this data along the retinohypothalamic tract to the SCN. This allows the brain to track day and night even with the eyes closed, ensuring the body doesn’t start its “day shift” at midnight.

Once the SCN knows it’s morning, it communicates with other brain regions to control hormone release. Its main target is the pineal gland, which produces melatonin, the hormone that signals “sleep time.” When daylight enters the eyes, the SCN sends inhibitory signals to the pineal gland, reducing melatonin production, while simultaneously increasing serotonin release, which enhances mood, focus, and wakefulness. This is why getting sunlight in the morning can lift energy and improve alertness.

As evening arrives and light levels drop, the SCN flips the switch. It stimulates the pineal gland to release melatonin, which makes you sleepy and ready to wind down. As darkness falls, melatonin levels rise and core body temperature drops, preparing the body for rest. Even in complete darkness, these cycles continue for a time, showing that they are internally generated — but without external light cues, they eventually drift out of sync. This is why we feel jet lag when travelling across time zones or struggle to sleep after using bright screens late at night. Melatonin also acts on the raphe nuclei — clusters of neurons in the brainstem that regulate serotonin — slowing brain activity and promoting relaxation.

This seesaw between serotonin by day and melatonin by night keeps you balanced: energetic and focused when the world is bright, tired and calm when it’s dark. Thanks to the SCN, your body doesn’t have to guess when to eat, move, or sleep — it already knows. But when this clock is thrown off, as in night shifts or scrolling on your phone at 2 a.m., your brain ends up thinking it’s sunrise and wonders why you’re lying down instead of making breakfast.

DAMAGE TO THE SCN

When the SCN (suprachiasmatic nucleus) is damaged or disconnected from light cues, circadian rhythms break down.

Key effects

Loss of 24-hour rhythm: Sleep–wake cycles, body temperature, and hormone secretion (e.g. melatonin, cortisol) become irregular or completely arrhythmic.

Free-running rhythms: If the SCN still functions but is isolated from light input, internal rhythms continue but drift out of sync with the external day–night cycle (about 24.2 hours in humans).

Animal studies: Lesions of the SCN in hamsters and rats abolish normal activity–rest cycles; transplanting an SCN from another animal restores rhythmicity.

In short, the SCN is the master clock. Damage destroys internal timing; isolation from light cues prevents entrainment to the environment.

SUMMARY

In essence, circadian rhythms act as the body’s master scheduling system. They coordinate countless processes — sleep, digestion, metabolism, alertness, and even cell repair — so that the body functions smoothly and efficiently across the 24-hour cycle.

Circadian rhythms regulate essential functions, including sleep, hormone release, metabolism, mood, and cognitive performance. They help the body anticipate regular environmental changes rather than merely reacting to them. When circadian rhythms are disrupted—through jet lag, shift work, or excessive screen exposure—the result can be fatigue, poor concentration, mood disturbance, and long-term health effects such as metabolic and cardiovascular problems.

OTHER EXAMPLES OF CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

Circadian rhythms also control other bodily processes that follow a daily rhythm. Body temperature is lowest in the early morning and highest in the early evening; blood pressure rises during the day and falls at night; and hormones such as cortisol peak around the time of waking to prepare the body for activity. Together, these patterns create a biological rhythm that matches our internal state to the external environment..

URINE PRODUCTION

Decreases at night to reduce sleep disturbance; increases during the day when activity levels rise, showing circadian control of kidney function.

DIGESTIVE ACTIVITY

The stomach and intestines show rhythmic activity, with peak acid secretion, enzyme release, and nutrient absorption during the day when eating is most likely.

LIVER METABOLISM

The liver’s detoxification and glucose regulation enzymes fluctuate across the 24-hour cycle, affecting how drugs and nutrients are processed.

CELL REPAIR AND DNA SYNTHESIS

Rates of tissue repair and DNA replication peak at night, indicating circadian regulation of cellular maintenance and regeneration.

IMMUNE FUNCTION

Activity of immune cells, such as lymphocytes and cytokines, varies throughout the day, with many immune responses heightened at night.

HORMONE RELEASE (GENERAL)

In addition to melatonin and cortisol, other hormones—including growth hormone—follow circadian rhythms, with secretion highest during early sleep to promote physical recovery and growth.

These examples show that while the sleep–wake cycle remains the core circadian rhythm, the SCN coordinates a vast network of peripheral rhythms across organs and systems, maintaining 24-hour balance in metabolism, repair, and behaviour.

RESEARCH STUDIES ON CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

Understanding of circadian disruption has been advanced through a range of different research methods, including case studies, lesion studies, transplant experiments, genetic and molecular research, and controlled human laboratory studies. Together, these approaches trace the brain’s internal timing mechanisms and reveal their physiological consequences. Research across several decades has shown that the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), its hormonal pathways, and underlying clock genes regulate daily biological rhythms — and that irregular light exposure, shift work, or jet lag can interfere with them.

SIFFRE AND OTHER ISOLATION STUDIES

SIFFRE (1962, 1975, 1999)

Michel Siffre conducted a series of influential self-experiments in sensory isolation to investigate whether human circadian rhythms continue without external time cues.

In his first study (1962) in the Alps, he lived in a cave for two months with no natural light, clocks, or social contact. When he resurfaced, he believed the date was weeks earlier than it actually was. His internal sense of time had drifted, and his sleep–wake cycle lengthened to around 25 hours, showing that biological rhythms continue but do not match the 24-hour day without environmental cues.

His second study (1975) was more controlled and lasted six months. Siffre lived alone in a Texas cave with regular monitoring via telephone. All external zeitgebers were removed. His free-running rhythm again settled slightly longer than 24 hours, sometimes drifting towards 30–48 hours. Periods of wakefulness extended and sleep onset became inconsistent. This reinforced the idea that humans possess a robust endogenous pacemaker capable of generating its own rhythm, but it is not perfectly aligned with the natural day-night cycle.

In his later study (1999), Siffre repeated the isolation experiment at age sixty. His circadian rhythm became even longer and more unstable, suggesting that the internal clock changes with age. Drift was greater, sleep became fragmented, and his rhythm fluctuated more widely. This provided rare evidence that endogenous pacemakers weaken or become less precise across the lifespan.

Across all studies, Siffre demonstrated that:

• humans have an internal biological clock;

• this clock persists without cues;

• it is not precisely 24 hours;

• without zeitgebers, the rhythm drifts, becomes unstable, and loses synchrony

CRITICISMS AND LIMITATIONS OF SIFFRE’S RESEARCH

Although Michel Siffre’s isolation studies (1962, 1975, 1999, 2007) were pioneering in demonstrating the existence of an endogenous circadian rhythm, they suffer from several critical methodological and interpretative weaknesses.

LACK OF GENERALISABILITY

A significant issue is that Siffre acted as both the researcher and sole participant in his early experiments. His findings, therefore, lack population validity and cannot be generalised across variables such as age, gender, or lifestyle. Later in life, Siffre repeated the procedure at the age of 60 and found his rhythm slowed considerably, suggesting that circadian timing changes with age. This further highlights the problem of using a single participant — the results may reflect individual variation rather than universal biological principles.ARTIFICIAL LIGHT AND LUX LEVELS

Siffre’s claim that his rhythm was “free-running” has been vigorously challenged by later research into light intensity (lux). Despite living in isolation from natural cues, he still used artificial lighting to see and work, assuming dim light had no biological effect. However, Czeisler et al. (1999) found that even low-intensity light (150–200 lux) can shift circadian phase and suppress melatonin, whereas ordinary daylight ranges from 10,000 to 100,000 lux. This means the “dim” lighting in Siffre’s cave was still bright enough to act as a weak zeitgeber, resetting his internal clock. His reported 25-hour rhythm may therefore be an artefact of light exposure rather than a truly endogenous cycle.INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND REPETITIONS

Siffre himself admitted that his rhythms varied between studies. In 1972, he reported a 25-hour cycle; in 1999, after spending time in a Texas cave, he found his sleep–wake pattern sometimes extended to 48 hours. This inconsistency raises doubts about replicability and suggests that stress, boredom, and cognitive factors (rather than pure biology) may have influenced his behaviour.TECHNOLOGICAL AND CONTROL LIMITATIONS

Siffre’s studies were conducted before modern light measurement and hormonal testing were available. He could not measure melatonin or cortisol levels, relying only on behavioural markers (sleep and wake times). As a result, his data lack the physiological precision of later work by Czeisler and Duffy at Harvard, who used controlled environments, measured lux levels, and tracked metabolic markers.THEORETICAL VALUE AND MODERN RELEVANCE

Despite these flaws, Siffre’s work remains historically significant. It provided the first direct evidence that humans possess an endogenous circadian pacemaker independent of external cues. However, modern circadian neuroscience—incorporating controlled lux levels, hormonal assays, and genetic analysis—has refined and corrected his conclusions. Contemporary evidence shows that the human clock averages 24 hours and 11 minutes, not 25, and is continually stabilised by light, temperature, and social zeitgebers.

OTHER CAVE AND ISOLATION STUDIES

ASCHOFF & WEVER (1976)

Participants lived in underground bunkers free of time cues for several weeks. Most developed free-running rhythms of 25–27 hours, supporting Siffre’s findings. A minority showed extreme drift beyond 30 hours, suggesting individual differences in pacemaker stability.

FOLKARD ET AL. (1985)

Further support comes from Folkard et al. (1985), who studied twelve participants living in temporal isolation for three weeks. They were cut off from natural light and agreed to follow a strict schedule of sleeping from 11.45 p.m. to 7.45 a.m. Unbeknownst to them, the researchers gradually sped up the experimental clock so that what appeared to be a 24-hour day actually lasted 22 hours. All but one participant continued to follow the shortened schedule, suggesting that while humans have a strong internal rhythm, it can be modified by external time cues. However, participants were not completely isolated from artificial light, which was later found to act as a weak zeitgeber capable of resetting the internal clock.

WEVER’s “ISOLATION UNIT” STUDIES

Wever repeated multiple trials examining circadian rhythms in isolation. Participants showed stable but slightly long rhythms, with many drifting toward 25–26 hours. Notably, some participants exhibited two concurrent rhythms (a “split rhythm”), indicating that different biological systems may drift to varying rates without external synchronisation.

RECHTSCHAFFEN & MORE (ANIMAL ISOLATION AND PACEMAKER LESION STUDIES)

Animal studies where the SCN was damaged or removed showed complete loss of circadian rhythmicity. Rats without an SCN displayed random sleep–wake patterns that no longer followed a 24-hour cycle. When SCN tissue from another animal was transplanted, rhythmicity returned—proof that the SCN is the endogenous pacemaker controlling circadian timing.

OVERALL CONTRIBUTION OF ISOLATION STUDIES

Together, these studies show that:

• Biological rhythms persist without external cues, proving the existence of endogenous pacemakers.

• The natural length of the human circadian rhythm is slightly over 24 hours, often around 25 hours.

• Without zeitgebers such as light, rhythms drift, become unstable, and desynchronise from each other.

• Light is the key zeitgeber required to anchor internal rhythms to the 24-hour world.

• There are individual differences in pacemaker precision and sensitivity to cues.

• Age affects the stability and length of the free-running rhythm.

This body of research forms the backbone of the AQA Biological Rhythms topic and provides the strongest empirical support for the interaction between endogenous pacemakers and exogenous zeitgebers.

ANIMAL STUDIES (ANIMAL ISOLATION AND PACEMAKER LESION STUDIES)

MOORE AND EICHLER (1972) first identified the SCN in the hypothalamus as the brain’s master circadian pacemaker. Animal studies showed that SCN lesioning in rats abolished regular sleep–wake and hormonal cycles, confirming that the SCN is the central timing structure. The SCN receives light input via the retinohypothalamic tract, and this discovery established the first direct neural pathway linking environmental light to biological timing.

RECHTSCHAFFEN & MORE Animal studies where the SCN was damaged or removed showed complete loss of circadian rhythmicity. Rats without an SCN displayed random sleep–wake patterns that no longer followed a 24-hour cycle. When SCN tissue from another animal was transplanted, rhythmicity returned—proof that the SCN is the endogenous pacemaker controlling circadian timing.

RALPH ET AL. (1990) demonstrated that these rhythms could be transferred biologically. By transplanting SCN tissue from mutant hamsters (with 20-hour cycles) into normal hamsters, the recipients adopted the donor’s shortened rhythm. This provided robust evidence that circadian timing is endogenously generated, rather than merely a response to external cues.

KING AND TAKAHASHI (1991). Later, molecular neuroscience identified the genetic basis for these internal rhythms. King and Takahashi (1991) isolated the first clock gene in mice, named CLOCK, and subsequent work by Reppert and Weaver (2002) identified a network of genes (PER1, PER2, CRY, BMAL1) that produce self-sustaining 24-hour oscillations in almost every cell of the body. These findings confirmed that the circadian system is hierarchical: the SCN coordinates the rhythm, but each organ contains its own molecular clock that can drift out of sync when external cues change too rapidly.

CLIFFORD SAPER (2018) A related experiment by Clifford Saper (2018) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre used mice exposed to a 20-hour light–dark cycle. The animals exhibited disturbed metabolic function, further suggesting that circadian misalignment disrupts energy balance and hormonal rhythms. Saper’s work also identified links between circadian timing and aggression, showing that disruption affects not only metabolism but also behavioural regulation through altered brain circuits in the hypothalamus.

STUDIES ON THE BLIND

MILES ET AL (1997)

Further evidence for the biological basis of circadian rhythms comes from Miles et al. (1977), who investigated a blind man born without light perception. Despite exposure to social cues such as clocks and routines, his circadian rhythm remained locked at around 24.9 hours. He was forced to take stimulants in the morning and sedatives at night to align his sleep with the 24-hour day. This demonstrates that exogenous zeitgebers such as social cues alone cannot override endogenous biological timing mechanisms.

Subsequent studies confirm that many totally blind people experience non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder, where their biological night gradually moves through the 24-hour day. However, some partially sighted individuals can still entrain to light because they retain functioning melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells, which detect brightness even without visual perception. This shows that light detection, not sight itself, is critical for circadian regulation.

Overall, evidence from blindness supports the conclusion that light is the dominant environmental cue for human circadian rhythms and that loss of light input to the SCN causes the body’s internal clock to free-run independently of the external world.

SLEEP DISRUPTION STUDIES

CZEISLER ET AL. (1999) later reported neuroimaging and electrophysiological research showing how environmental disruption affects human brain activity. Czeisler et al. (1999) demonstrated that exposure to low-intensity artificial light (150–200 lux) can shift circadian phase and suppress melatonin, overturning Siffre’s assumption that dim light has no biological effect. Subsequent fMRI studies in the 2000s revealed that when the SCN is misaligned — as in shift work or jet lag — activity in the prefrontal cortex decreases, impairing decision-making and attention. At the same time, abnormal signalling between the SCN and amygdala increases emotional reactivity.

BUIJS ET AL. (2003. Neuroscience has also shown how circadian desynchrony affects stress and metabolism. Disruption of the SCN leads to dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in cortisol peaks at inappropriate times and heightened anxiety and cardiovascular strain (Buijs et al., 2003). Peripheral clocks in organs such as the liver and heart also fall out of phase, explaining why irregular shift work is associated with metabolic disorders, diabetes, and obesity (Hastings et al., 2007).

ARENDT (2010) and colleagues used molecular assays to show that after long-distance flights, the SCN adjusts to new time zones faster than peripheral tissues, leaving the body in temporary internal desynchronisation — the physiological basis of jet lag. The re-synchronisation of gene expression across these tissues can take several days, consistent with subjective recovery times reported by travellers.

JEAN DUFFY ET AL. (2018) Recent laboratory research provides strong modern evidence for how circadian disruption affects human physiology and long-term health. At Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), Jeanne Duffy et al. (2018) conducted a controlled study in which volunteers lived for a month in windowless, soundproof rooms without any external time cues. Participants followed a 28-hour sleep–wake cycle, delaying sleep and meals by four hours each day while researchers measured glucose, insulin, and other metabolic markers. The findings showed that prolonged misalignment between internal circadian timing and external routines impaired glucose regulation and insulin sensitivity, mimicking early signs of type 2 diabetes. This supports epidemiological data showing that night-shift workers are more prone to weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. The study demonstrated that even when total sleep time and calorie intake were controlled, shifting the timing of sleep and eating disrupted metabolism — confirming that when we eat and sleep, timing matters as much as quantity.

RESEARCH EVALUATION CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

WHAT EVERYDAY APPLICATION COULD WE GAIN FROM THESE STUDIES?

DOES THE RESEARCH TELL US WHICH IS MOST IMPORTANT: ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKERS OR EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS?

RESEARCH SYNOPSIS

Taken together, research findings show a clear chronological progression

(1972) Identification of the SCN as the master clock.

(1990) Experimental proof that circadian timing is endogenous and transplantable.

(1991–2002) Discovery of molecular clock genes in the SCN and peripheral tissues.

(1999–2003) Demonstration that artificial light and shift work disrupt melatonin and cortical activity.

(2007–2010) Evidence linking circadian desynchrony to hormonal, metabolic, and cognitive dysfunction.

This body of evidence shows that circadian rhythms are hardwired into both neural and genetic systems. Deep within the brain, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) coordinates timing signals, while inside nearly every cell, clock genes such as CLOCK, BMAL1, PER1–3, and CRY1–2 create self-sustaining feedback loops. These genes encode proteins that oscillate in a roughly 24-hour cycle, regulating metabolic, hormonal, and behavioural rhythms. Remarkably, these molecular oscillations persist even in constant darkness or under stable conditions, proving they are endogenously generated rather than driven by the environment.

Although the circadian system can adapt gradually to seasonal or latitudinal changes, it remains biologically constrained. The human body is finely tuned to the Earth’s 24-hour rotation. It is easily destabilised by the rapid, irregular demands of modern life, such as shift work, jet lag, and exposure to artificial light.

UNIVERSALITY OF CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

The fact that circadian rhythms exist in almost identical form across the living world is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that they are driven by powerful endogenous mechanisms rather than just external cues. FROM PLANTS TO HUMANS – THE SAME BASIC DESIGN

As early as 1729, Jean-Jacques de Mairan showed that mimosa plants continue to open and close their leaves on a ~24-hour cycle even in constant darkness – proving that an internal clock exists.

In 1971, Konopka & Benzer discovered the first clock gene (period) in fruit flies; mutants with a broken period gene had 19-hour, 28-hour, or no rhythms at all, even in regular light-dark cycles.

The same core molecular feedback loop (PER, CRY, CLOCK, BMAL1 proteins) is found in plants, fungi, insects, fish, mice, and humans.

MAMMALIAN SYSTEM – UNIVERSAL BUT HIERARCHICAL

In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) acts as the master pacemaker, but almost every cell in the body has its own peripheral clock running the same genetic loop. These tissue clocks are usually kept in perfect phase by the SCN. Still, they can also be shifted independently by feeding time, exercise, or temperature – exactly the mechanism seen in flies and plants.

WHY UNIVERSALITY MATTERS FOR THE ENDOGENOUS VS EXOGENOUS DEBATE

If circadian rhythms were mainly a passive response to external zeitgebers, we would expect huge differences between species and little need for conserved clock genes. Instead:

The molecular machinery is remarkably similar from algae to humans.

Rhythms persist (free-run) in constant conditions in every organism studied.

Disruption of the clock genes produces the same kinds of sleep, metabolic, and mood disorders in flies, mice, and humans.

CONCLUSION – A UNIVERSAL ENDOGENOUS DESIGN

The near-universal presence of the same genetic oscillator across the kingdoms of life demonstrates that circadian timing is a fundamental, evolved biological property rather than an environmental imposition. Exogenous zeitgebers are essential for synchronisation, but the core 24-hour rhythm is built into the organism itself. This universality underpins everything from plant agriculture to human chronotherapy. It explains why shift work and jet lag are so damaging – we are fighting a clock that has been ticking inside living things for hundreds of millions of years.

REAL-LIFE APPLICATION OF CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS: CHRONOPHARMACOLOGY

Circadian rhythms have practical consequences for health and behaviour. Many physiological processes—such as metabolism, hormone release, alertness and enzyme activity—rise and fall across the 24-hour cycle. As a result, some medications work better at certain times of day (a field known as chronopharmacology). For example, blood-pressure drugs are often more effective when taken in the evening because that is when nighttime blood pressure begins to rise. At the same time, asthma medication may be more beneficial later in the day when lung function naturally dips. Even pain sensitivity, reaction time and cognitive performance follow daily circadian patterns. The timing of drug dosing has been studied for anticancer, cardiovascular, respiratory, anti-ulcer, and anti-epileptic drugs (Baraldo, 2008).

PLEASE NOTE

PHARMACOKINETICS

What the body does to the drug (absorbs it, spreads it around, breaks it down, gets rid of it).

That’s it. It’s just the science of how drugs move inside you.

Circadian rhythms can change how fast or slow these things happen during the day, but the word itself doesn’t mean “choosing the best time to take the medicine”.

CHRONOPHARMACOLOGY

Giving the drug at the perfect time of day on purpose because you know the body clock makes it work better (or have fewer side effects) at that time.

Examples: blood-pressure tablets at night, asthma inhalers in the evening, some cancer drugs at specific hours. WHICH ONE IS THE REAL-LIFE

APPLICATION OF CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS?

Chronopharmacology.

WHY TEXTBOOKS AND TEACHERS KEEP SAYING “PHARMACOKINETICS” INSTEAD

Circadian rhythms change things like liver activity and blood flow during the day → these changes do affect pharmacokinetics → teachers and books therefore say “circadian rhythms affect pharmacokinetics” and stop there.

They never take the next step and say the actual application is choosing the best time to give the drug.

So the word “pharmacokinetics” is misused as the whole answer when the question is about practical use (i.e., timing the dose = chronopharmacology).

BOTTOM LINE FOR YOUR EXAM

If the question says “application”, “example”, or “importance” of circadian rhythms in medicine, describe the timing of the drug (e.g., blood-pressure drugs at night) and, if you want to be precise, call it chronopharmacology. Do not just write “pharmacokinetics”.

SHIFT WORK AND JET LAG: DISRUPTION BY EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS

Exogenous zeitgebers are the external cues (light, meal times, social schedules, temperature) that usually keep our endogenous circadian rhythm locked to the 24-hour day. When these cues become inconsistent or change too quickly, the master clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and the peripheral clocks in organs such as the liver and heart lose synchrony. Rotating shift patterns are particularly damaging because the body never has enough days to fully re-entrain before the next switch. Permanent night shifts, although still unnatural, allow partial re-entrainment when light and meals are kept consistent. Jet lag works the same way on a shorter timescale: rapid travel across time zones abruptly disrupts the light-dark cycle, and eastward travel is harder because it requires a phase advance (shortening the day). In contrast, westward travel only requires the easier phase delay.. For this reason, unless constantly travelling across time zones, jet lag is less disruptive than shift work.

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES OF MISALIGNMENT

The result is internal desynchronisation. Performance crashes at the circadian trough around 4–6 a.m., producing the well-documented rise in accidents at the end of night shifts (Boivin et al., 1996). Long-term effects include chronically low melatonin, high cortisol, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and a threefold increase in cardiovascular disease (Knutsson, 2003). Shift work is also linked to higher rates of breast cancer, gastrointestinal disorders and mood disturbance. As Russell Foster (2013) emphasises, persistent disruption of the sleep-wake cycle impairs memory consolidation, weakens immune function, destabilises mood and significantly raises the risk of dementia and early death.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS: USING EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS TO RE-ALIGN THE SYSTEM

Because conflicting zeitgebers cause the problem, we can deliberately control the same cues to restore alignment:

Deliver bright light (>1000 lux) immediately after waking, whatever time that is.

Create complete darkness, cool temperature (16–18 °C) and quiet during intended sleep hours, even if that sleep occurs in daylight.

Keep meal times fixed to entrain the liver’s food-entrainable oscillator.

Avoid caffeine, alcohol and blue light in the biological evening.

Use blackout blinds, eye masks and earplugs to block unwanted light and noise.

For jet lag, gradually shifting light exposure and meal times in the days before travel dramatically shortens recovery time.

WIDER SOCIETAL BENEFITS

When individuals apply these evidence-based adjustments, accident rates in healthcare, transport and industry fall, absenteeism decreases, and the long-term burden of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and mental health problems is reduced. The NHS benefits directly from lower demand for treatment of these largely preventable conditions, while employers gain a healthier, more reliable workforce. Understanding exogenous zeitgebers, therefore, provides low-cost, high-impact solutions to some of the biggest health challenges created by modern 24-hour society.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

The idea that everyone’s body clock runs in the same way is a myth. Even when people live in the same time zone and are exposed to identical light-dark cycles, huge differences appear in preferred sleep-wake times, peak alertness, and overall circadian phase.

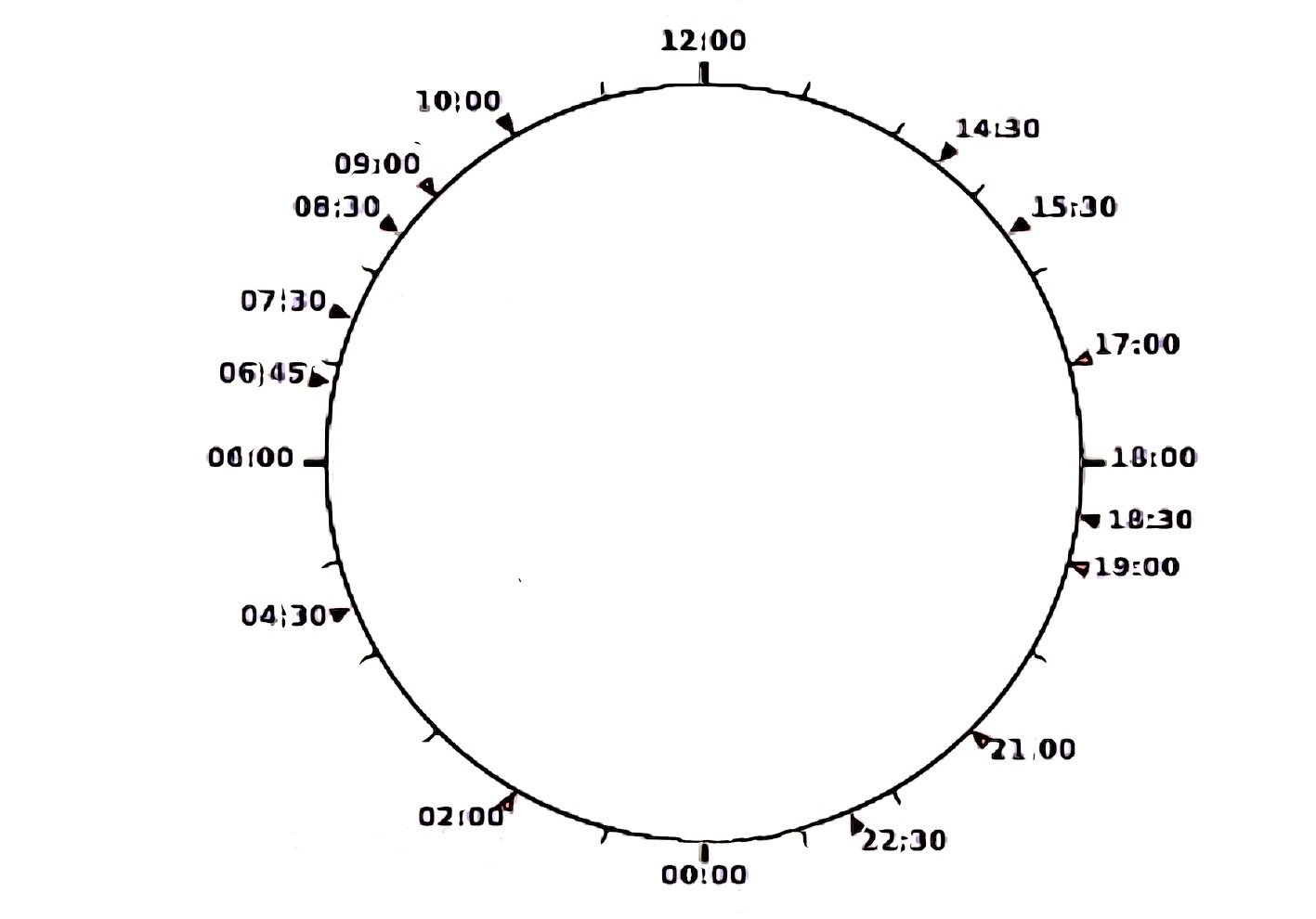

MORNINGNESS VS EVENINGNESS (CHRONOTYPES)

Duffy et al. (2001) showed that “morning people” (larks) naturally wake around 6 a.m., feel most alert in the early part of the day, and prefer to sleep by 10 p.m. “Evening people” (owls), in contrast, struggle to wake before 9–10 a.m., reach peak performance in the late afternoon/evening, and do not feel sleepy until 12–2 a.m. or later. These preferences are remarkably stable across the lifespan and are seen worldwide.

WHY THIS MATTERS FOR EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS

Both larks and owls experience the same sunrise, sunset, and artificial light patterns, yet their internal clocks are offset by several hours. This proves that exogenous zeitgebers such as light, while powerful, are not the whole story. The same light exposure advances the clock of a morning person but may have a much weaker or delayed effect on an evening person. In other words, the strength and timing of responses to external cues vary biologically across individuals.

BIOLOGICAL AND GENETIC BASIS

Chronotype is highly heritable (around 40–50 %). Twin studies and genome-wide association studies have identified multiple “clock gene” variants (e.g., PER3, CLOCK) that lengthen or shorten the intrinsic period of the circadian cycle. Morning types tend to have a slightly shorter intrinsic period (<24 h), making it easier for them to phase-advance in response to morning light. In contrast, evening types often have a longer intrinsic period (>24 h), which resists early waking.

DEVELOPMENTAL CHANGES: AGE DIFFERENCES IN CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS

A common student critique of the role of exogenous zeitgebers runs like this:

“If light and social cues are so powerful, why do sleep patterns change so dramatically across the lifespan? Babies sleep around the clock, teenagers won’t get up before lunchtime, and grandparents are awake at 5 a.m. Doesn’t this prove that external zeitgebers override the internal clock?”At first glance, it looks convincing. In reality, these age-related shifts are driven by biological changes in the endogenous circadian system itself, not by external cues winning the battle.

DEVELOPMENTAL CHANGES – BIOLOGY, NOT ENVIRONMENT

Newborns have no stable 24-hour rhythm at birth. Melatonin only becomes rhythmic around 3 months, and cortisol between 2–9 months (NCBI, 2023). Until then, sleep is scattered because the endogenous pacemaker is still maturing.

Adolescence triggers a programmed 2–3 hour delay in melatonin release – the biological cause of the famous teenage “sleep phase delay”. It happens in every culture, even when school start times and light exposure are identical to those of adults.

In older age, melatonin production drops, circadian amplitude weakens, and sleep fragments, pushing wake times earlier.

These are endogenous developmental changes, not evidence that external zeitgebers are taking over.

CONCLUSION

These findings show that circadian rhythms are biologically flexible and individually unique. Development, genetics, and lifestyle interact to produce distinct sleep–wake patterns, highlighting that the human circadian system is an adaptive, not uniform, mechanism.

REAL-WORLD APPLICATIONS — ARTIFICIAL LIGHT AND TECHNOLOGY

Modern environments expose people to artificial light far beyond what the brain evolved to handle. The human internal clock (regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN) depends on natural light as its main zeitgeber—but artificial lighting, especially from screens and LED bulbs, interferes with this system.

Light intensity, measured in lux, is key. Natural daylight can exceed 10,000–100,000 lux, while indoor lighting averages only 150–500 lux, and most screens emit around 30–150 lux. Although weaker overall, LED and phone screens emit a high proportion of blue light (≈480 nm), which stimulates melanopsin-containing retinal cells that send light signals to the SCN. This tricks the brain into thinking it is still daytime, suppressing melatonin and delaying sleep onset.

Evidence from Czeisler et al. (1999) demonstrated that even dim light (150–200 lux) can shift circadian phase, showing that ordinary indoor illumination is enough to disrupt the body clock. Subsequent cognitive neuroscience studies using fMRI have shown that evening light exposure alters neural activity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, impairing memory consolidation, attention, and emotional regulation. Long-term disruption is associated with insomnia, depression, and metabolic disorders.

These findings have clear real-world implications. They explain why using phones or laptops before bed can delay sleep and reduce rest quality, and why exposure to bright screens in the evening contributes to widespread sleep disturbance in modern societies. Understanding the relationship between lux levels, wavelength, and SCN signalling has informed practical solutions such as blue-light filters, night-shift lighting, and circadian-based light therapy to restore alignment between the internal clock and the natural light–dark cycle.

CULTURAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL VARIATION IN CIRCADIAN RHYTHMS: WHY LIGHT IS NOT ALWAYS THE STRONGEST ZEITGEBER

In almost every discussion of circadian rhythms, light is treated as the overwhelmingly dominant exogenous zeitgeber. This emphasis is understandable – light is powerful and easy to study – but it quietly assumes the same rule applies to every human on Earth. When we look at people living in extreme environments, that assumption collapses.

EQUATORIAL REGIONS – TEMPERATURE EASILY OVERPOWERS LIGHT

At the equator, the day is 12 hours long every single day of the year. Light-dark variation is tiny and gives almost no daily timing information. Instead, the daily temperature cycle takes over. Core body temperature drops in the early afternoon, exactly when external heat peaks; alertness crashes, and the siesta is born. From southern Spain and Italy to Mexico, Nigeria, the Middle East and Southeast Asia, afternoon rest is universal for the same biological reason. Buhr et al. (2010) showed that temperature swings of less than 1 °C are enough to entrain peripheral clocks even when light is constant. When the environment becomes hotter than the body can comfortably handle, temperature becomes a stronger zeitgeber than light.

HIGH-LATITUDE EXTREMES – NATURAL LIGHT VANISHES FOR MONTHS

Above the Arctic Circle (northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, Alaska, Siberia) the sun disappears completely in winter and never sets in summer. For half the year, there is no daily light-dark cycle at all. Pre-industrial populations did not force a single consolidated night's sleep. They used biphasic or polyphasic patterns and relied on social zeitgebers (fixed meals, prayer, communal storytelling) and behavioural cues tied to twilight. Even today, the total absence of natural light-dark contrast still causes widespread winter insomnia and summer sleep disruption unless people deliberately create artificial cues (dawn simulators in winter, blackout curtains in summer).

EVOLUTIONARY REASON: THE SCN IS FLEXIBLE, NOT RIGID

A completely fixed, light-only clock would have been lethal for early humans. The group always needed some individuals awake at night to tend the fire, guard the camp, nurse infants, care for the sick, or watch for predators and dawn hunting opportunities. Natural selection, therefore, favoured a circadian system that could prioritise whichever zeitgeber was most reliable and survival-critical in the local environment: light on the open savannah, temperature near the equator, social and activity cues in forests or polar regions. Studies of present-day hunter-gatherers and historical records (Ekirch, 2005; Yetish et al., 2015) confirm that segmented sleep with a natural wakeful period around 2–3 a.m. was the ancestral pattern – ideal for quiet vigilance when danger was highest.

MODERN EVOLUTIONARY MISMATCH

The same flexibility that allowed us to colonise every habitat now works against us. Artificial electric light (only ~140 years old), blue-rich screens, transatlantic flights, night shifts and 24-hour society give us weak, conflicting zeitgebers that our biology never evolved to handle. The SCN still expects the strong, clear signals our ancestors had; instead, we live in perpetual mild desynchronisation, paying for it with rising rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer and mood disorders.

CONCLUSION

Human circadian rhythms are not universally light-driven. The system evolved to detect and follow whichever zeitgeber best predicts survival conditions in a given habitat. This built-in flexibility explains equatorial siestas, high-latitude segmented sleep, and why modern artificial environments are making so many of us ill. It removes the ethnocentric bias that treats light as the only “proper” zeitgeber and shows the human circadian system for what it really is: a highly adaptive, interactionist mechanism shaped by both nature and nurture.

REDUCTIONISM: BIOLOGICAL RHYTHMS CANNOT FULLY EXPLAIN SLEEP BEHAVIOUR

Although the SCN sets the timing of the sleep–wake rhythm, it does not control sleep on its own. Other neural systems are essential for initiating and maintaining sleep. The VLPO in the hypothalamus triggers sleep by releasing GABA to inhibit wake-promoting neurons. At the same time, the ARAS in the brainstem keeps the brain alert through neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and norepinephrine. Orexin pathways stabilise wakefulness, and loss of orexin cells causes narcolepsy. These systems show that the SCN only determines when sleep should occur; it does not determine whether sleep actually happens.

This means that explanations based solely on circadian pacemakers are biologically reductionist, because they overlook the broader network of mechanisms required for regular sleep. A complete account of sleep behaviour must therefore include both the timing provided by biological rhythms and the neural systems that control sleep states themselves.

INFRADIAN RHYTHMS

Another crucial biological rhythm is the infradian rhythm. Infradian rhythms last longer than 24 hours and can be weekly, monthly or annually.

Two examples of these are:

The Menstrual Cycle

Biannual Oestrus in some mammals

THE ENDOGENOUS PACEMAKER FOR THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The menstrual cycle is a clear example of an infradian rhythm because it follows a repeating biological pattern that lasts longer than twenty-four hours, typically around twenty-eight days. It consists of a predictable sequence in which the body prepares for the possibility of pregnancy. The cycle begins with menstruation, when the uterine lining is shed. After this, hormone levels rise and the lining begins to regenerate. Midway through the cycle, a surge in luteinising hormone triggers ovulation. If fertilisation does not occur, levels of oestrogen and progesterone fall, causing the lining to break down and initiating the next cycle. Although the exact length varies between individuals, the overall pattern is regular and cyclical, which is why it is classified as an infradian rhythm.

An endogenous pacemaker governs this rhythm: the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. At the centre of this system is the hypothalamus, which sets the pace of the cycle by releasing pulses of GnRH. These pulses instruct the pituitary gland when to release FSH and LH, which control follicle development and ovulation. In turn, the ovaries produce oestrogen and progesterone, and these hormones feed back to the hypothalamus and pituitary to regulate the next stage of the cycle. This closed feedback loop allows the menstrual rhythm to continue in a coordinated monthly pattern, even without external cues.

Across the cycle, these hormonal fluctuations can also affect mood, energy and behaviour. Rising oestrogen in the first half of the cycle is associated with increased motivation and cognitive clarity. The LH surge around ovulation often coincides with heightened vitality and sexual interest. Later in the cycle, falling progesterone can contribute to premenstrual symptoms such as irritability or low mood. These effects occur because the hormones that regulate the cycle also influence brain function. They do not alter the timing of the rhythm itself but show how infradian processes can produce psychological and behavioural changes.

Taken together, the menstrual cycle demonstrates how an infradian rhythm is internally organised by a biological pacemaker. A sequence of hormonal signals generates a stable monthly pattern and produces characteristic physiological and psychological changes as the cycle progresses

IN SUMMARY

The menstrual cycle is an infradian rhythm because it repeats roughly every 28 days. It is controlled internally by the HPO axis, which releases hormones in a fixed order to prepare the body for pregnancy. These hormones also affect mood and energy, with oestrogen lifting mood earlier in the cycle and falling progesterone causing premenstrual symptoms later on. It is a clear example of an internal biological rhythm that repeats monthly

EXOGENOUS ZEITGEBERS OF THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The menstrual cycle is an infradian rhythm generated internally by the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian system, but it does not operate in a vacuum. Infradian reproductive rhythms evolved to adapt to the broader environmental landscape because successful reproduction depends on long-term conditions rather than moment-to-moment cues. For this reason, external factors act as exogenous zeitgebers—not by “resetting” the cycle as light resets the SCN, but by modulating the phase, stability, and regularity of the rhythm in response to the outside world. These zeitgebers operate over weeks or months, reflecting the adaptive need to align fertility and reproduction with environmental safety, resource availability and social context.

SOCIAL AND PHEROMONAL CUES

Social context is a potential zeitgeber because reproductive timing historically benefited from cooperative breeding, resource sharing and synchronised childrearing. Even though evidence is mixed, the idea is psychologically coherent:

Group living creates shared environmental patterns that influence behaviour and emotional states.

Exposure to others’ pheromonal or behavioural cues may provide information about social structure, safety and coordination.

Infradian rhythms evolved under conditions where synchrony increased offspring survival—not necessarily through perfect alignment, but through shared labour and protection.

Thus, social cues act as potential zeitgebers not because they “trigger ovulation,” but because they serve as social-environmental information that may interact with monthly timing.

RESEARCH ON SOCIAL / PHEROMONAL CUES AS A ZEITGEBER

SUPPORTING STUDIES

McClintock (1971)

Observed synchronisation of menstrual onsets among 135 dormitory students. Interpreted as menstrual synchrony driven by social/pheromonal cues.

Russell, Switz & Thompson (1980)

Applied underarm sweat from donors to recipients’ upper lips. Recipients showed small shifts in cycle timing toward the donor’s cycle phase.

Weller & Weller (1992, 1993, 1997)

In multiple cohabiting groups (mother–daughter pairs, kibbutz communities, lesbian couples), menstrual onsets moved somewhat closer together over time.

Cutler, Friedman & McCoy (1998) – MISSING ON MOST A-LEVEL PAGES

Found that exposure to synthetic putative human pheromones increased the likelihood of regular cycles and ovulation in women using pheromone-infused perfume. Suggested external olfactory cues can influence cycle regularity.

Preti et al. (2003) – ALSO MISSING FROM SCHOOL SITES

Showed that compounds from women’s axillary secretions applied to other women produced modest timing shifts in LH surge patterns, suggesting odour-mediated cycle influence.

Stern & McClintock (1998)

Daily application of axillary secretions (pads worn under arms) from donors at different cycle phases shifted cycle timing in 68 per cent of recipients toward the donor phase.

CRITICAL AND DISCONFIRMING STUDIES

Wilson (1991)

Repeated McClintock’s dormitory study with better controls and found no synchrony beyond chance expectation.

Strassmann (1997, 1999)

A long-term prospective study of Dogon women (natural fertility) found no menstrual synchrony at all, even under ideal conditions for detecting it.

Yang & Schank (2006)

A large sample (N = 186) in Chinese dormitories showed no synchrony and demonstrated how “synchrony” appears statistically by chance when cycle lengths vary naturally.

Schank (2006)

A comprehensive review concluded that evidence for human menstrual synchrony is weak, inconsistent, and methodologically flawed, and that pheromonal influence is minimal at best.

Treloar et al. (1967–1970 longitudinal cohort) – RARELY TAUGHT, BUT IMPORTANT

Showed huge natural variability in cycle length across months and individuals, meaning synchrony can appear by coincidence in groups of women. Undercuts claims of pheromone effects.

Jern & Haukka (2015) – CONTEMPORARY STUDY

A large dataset of couples and cohabiting women found no synchrony, challenging the assumption that close contact reliably shifts menstrual timing.

STRESS AS A ZEITGEBER

Stress affects the menstrual cycle because chronic sympathetic arousal communicates an extended period of threat, instability or unpredictability. Unlike circadian rhythms, which depend on a single, non-negotiable environmental cue (light), the menstrual cycle integrates ecological cues. Sustained stress signals that the external world may not support pregnancy or infant survival.

This happens for several interconnected psychological and biological reasons:

Sympathetic dominance prioritises mobilisation of resources for vigilance, defence and action. Reproductive timing is deprioritised because pregnancy requires sustained internal stability rather than acute reactivity.

HPA-axis activation creates a long-term profile of arousal that competes with reproductive rhythms. This does not simply “switch off” the cycle; it introduces noise and instability into the pattern, shifting the cycle length, the onset of ovulation, and hormonal coherence.

Environmental inference: from an evolutionary psychology perspective, stress serves as informational input about danger, scarcity or disruption within the habitat. Reproductive timing adjusts because these contexts reduce the likelihood that offspring will survive.

Stress (umbrella zeitgeber)

– includes sympathetic arousal

– chronic unpredictability

– threat cues

– instability

– significant environmental changes (relocation, lifestyle disruption, dramatic shifts in routine)

– prolonged cognitive/emotional load

– extended physiological demand

Thus, stress functions as a contextual zeitgeber—a long-term environmental signal integrated into the infradian rhythm's pacing.

This is deep, rhythm-specific, and qualitatively different from circadian entrainment.

RESEARCH ON STRESS AS A ZEITGEBER

STRESS FROM WAR, DISASTER, AND EXTREME EVENTS

Grof & Schreiber (1976) – Earthquake stress and menstrual disturbance. After the 1971 San Fernando earthquake, women living in the affected region showed significantly higher rates of cycle length changes, delayed menstruation, and amenorrhoea compared with unaffected populations.

Largillier, 1983 – Lebanese Civil War study: Women exposed to chronic wartime stress displayed increased rates of oligomenorrhoea (infrequent menstruation) and cycle irregularity compared to those outside the conflict zone.

Morris & Udry (1970) – Bereavement: Women's cycles became irregular following the death of a close family member, with disrupted ovulation patterns for several months.

Hui et al. (2014) – Wenchuan earthquake: Adolescent girls in the earthquake zone reported increased menstrual irregularity for several months post-disaster compared with controls in neighbouring regions.

Implication: major environmental upheaval influences menstrual timing at the population level.

EXAM STRESS AND CHRONIC ACADEMIC PRESSURE

Harlow et al. (1996) found that university students showed longer, shorter, or skipped cycles during sustained academic stress (exam terms), not during isolated stressful events.

Nillni et al. (2011) Large sample of college students: high perceived stress was associated with cycle irregularity and variable cycle length, independent of lifestyle factors.

Implication: Psychological stress functions as a contextual zeitgeber over weeks to months.

HPA–HPG AXIS INTERACTION (MECHANISTIC EVIDENCE)

Berga & Loucks (2006) – Functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea: Women under chronic stress show elevated cortisol and significantly reduced GnRH pulsatility, disrupting ovulation—implication: chronic HPA activation interferes with reproductive timing mechanisms.