LONG TERM MEMORY

LONG-TERM MEMORY (THE PAST)

What happens to our old short-term memories? In other words, where do prior short-term memories go when attention is directed to new short-term memories? According to research, most of our short-term memories decay or get displaced, e.g., they are pushed out of the STM store to make room for new short-term memories; the bottom line is that most are lost forever.

Thankfully, some of our STM data gets transferred to long-term memory stores. But what is long-term memory?

In short, long-term memory is the record of who we are as individuals and all we have learned; it is the backstory of our lives, personalities, experiences, and knowledge. Without LTM, we could not speak, identify objects or even walk. The world would be puzzling, chaotic, and devoid of meaning. We would relive the same moments repeatedly. It would be akin to being a newborn, in which the world lacks concepts or schemas.

Contrary to popular belief, the essence of who we are does not reside in our DNA but lives in our long-term memories. So if you are hoping to achieve eternal life by cloning or reincarnation, then you will be sadly disappointed. All you would achieve by cloning yourself is creating an identical (MZ) twin. Although MZ twins share identical genes, they are two distinct individuals with different autobiographical histories and memories. Likewise, if you end up being reincarnated after death but can’t remember your previous life and identity, then it is going to be a pretty unrewarding afterlife.

Besides, for all you know, you may have been reincarnated several times already. Still, if this is true, you won’t care about your past existences because if you can’t recall previous friends, relatives and experiences, then who are you?

Incidentally, this is why I didn’t rate the film The Matrix. If you saw it, do you remember when the traitor Cypher told Smith that he wanted to have his memory erased and be reinserted into the Matrix because "ignorance is bliss?” But Cypher would have experienced no greater bliss by being reinserted into the Matrix than by being killed. If he did not remember his former existence, how could he benefit from the contented ignorance brought about by taking the blue pill? In reality, the blue Pill and death would have both achieved the same thing: termination of the former self.

All forms of Dementia are characterised by the brain’s inability to transfer short-term memories into long-term memories. Thus, long-term memory can be considered as the total of the self.

To sum up, if you can remember something that occurred more than a few moments ago, whether hours ago or decades earlier, it is a long-term memory you accessed. Long-term memory also refers to the indefinite retention of information over a lifetime. This type of memory tends to be stable and has a seemingly never-ending capacity.

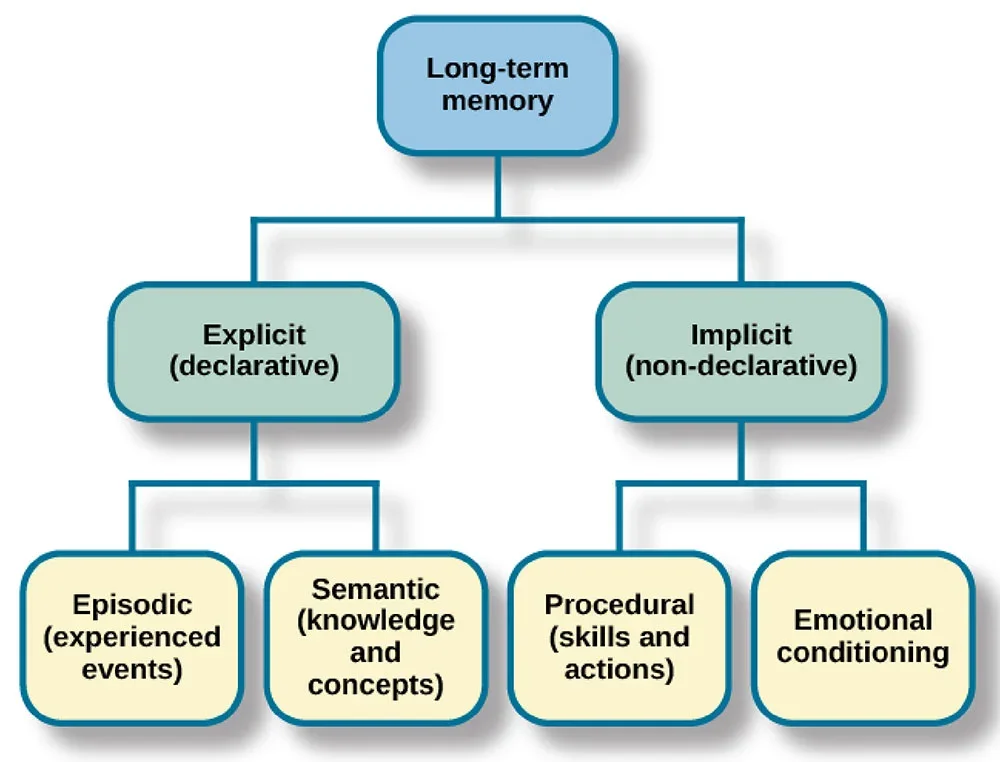

Long-term memory can be subdivided into explicit (conscious) and implicit (unconscious).

https://www.totalbrain.com/mental-health-assessment/memory-test/

DECLARATIVE/EXPLICIT VERSUS NON-DECLARATIVE/ IMPLICIT MEMORIES

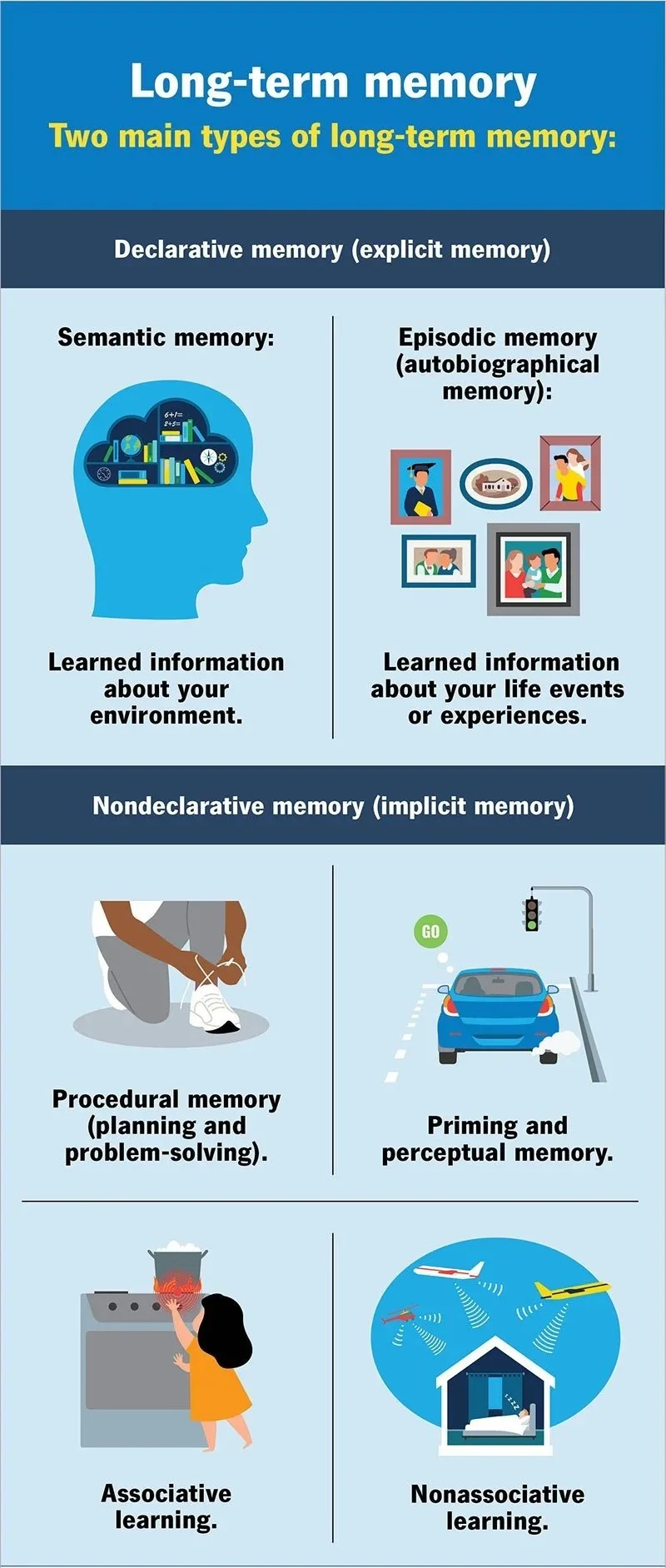

Long-term memory (LTM) can be divided into two types:

Explicit/ Declarative and Conscious.

Implicit/Non-Declarative and Unconscious.

Declarative memory encompasses memories that can be consciously recalled and articulated, such as facts, knowledge, and personal experiences. This form of memory allows individuals to "declare" what they know, whether by recounting a past event (e.g., describing a birthday celebration) or by recalling factual knowledge (e.g., naming the capital of a country). Declarative memory derives from the ability to retrieve and explicitly verbalise stored information.

Episodic and semantic memory are forms of declarative memory, as they involve explicit recall and deliberate retrieval. For example, episodic memory enables vivid recall of specific personal experiences. In contrast, semantic memory enables you to share general facts or concepts without being tied to any particular time or place.

In contrast, non-declarative memory operates unconsciously, allowing individuals to retrieve information or perform actions without deliberate effort. For instance, riding a bike relies on procedural memory, a form of non-declarative memory that stores motor skills and habits. Unlike declarative memory, procedural memory cannot easily be articulated; if asked to explain how you ride a bike, you might struggle to describe the intricate processes, such as the exact coordination of muscles or balance required to keep the bike in motion. Instead, you act automatically, demonstrating the difference between declarative and non-declarative systems.

This distinction highlights the dual nature of long-term memory and underscores declarative memory's specificity in enabling conscious, explicit access to knowledge and experiences.

EXPLICIT OR DECLARATIVE MEMORY - “knowing that”

Memories that you consciously work to recall are known as explicit memories, such as recalling items on your shopping list. Explicit memory is also referred to as conscious or automatic memory because it is both mindful and intentional.

Explicit memory is often called declarative memory since you can declare (say) what you remember. This is because explicit memories can be verbally explained, e.g., what you did at the party, a book review, or the Capital of Ghana.

There are two types of explicit/declarative memory: semantic and autobiographical/episodic.

KEYWORDS: DECLARATIVE, CONSCIOUS, KNOWING THAT, EXPLICIT AND INTENTIONAL

IMPLICIT OR NON-DECLARATIVE MEMORY - knowing how.”

Memories that are recalled unconsciously, unintentionally, and effortlessly are known as implicit, conscious, or automatic memories.

Implicit memory is also often called non-declarative since you cannot consciously bring it into awareness or describe it. It is a previously learned motor skill, such as talking, writing, biking, walking, or swimming. Implicit memories are often procedural, focusing on the step-by-step processes required to complete a task. We call it muscle memory in animals.

Where explicit memories are conscious and can be verbally explained, implicit memories are usually non-conscious and not easily articulated. Try describing to someone how you swim or ride a bike.

There are two types of implicit (non-declarative) memory: procedural and emotional conditioning.

NON-DECLARATIVE MEMORY

There are four subtypes of nondeclarative memory: but aqa you only need to know procedural

Procedural memory: This is the information needed to help you perform tasks. It combines executive skills (such as planning and problem-solving) and motor skills (the coordination of muscle movements).

Priming and perceptual memory: You can relate something you previously had exposure to in your memory to help you process and learn new information.

Associative learning (classical conditioning): This is linking one thing in your memory with another. It helps you make connections between information you already learned and new information.

Nonassociative learning: the process of adjusting how you respond to a stimulus over time. It helps you respond to environmental stimuli.

Examples of the subtypes of nondeclarative memory include:

Procedural memory: You tie your shoes or turn on your phone.

Priming and perceptual memory: You see the colour red and select a stop sign, based on your knowledge that the sign shares the same colour.

Associative learning: The most common example in history is Pavlov’s dog, where a dog salivates when it hears a bell. The dog associated the sound with being fed.

Nonassociative learning: You purchase a new refrigerator and hear it running constantly. Over time, you adjust to the noise and the sound no longer bothers you.

KEYWORDS: NON-DECLARATIVE, UNCONSCIOUS, KNOWING HOW, IMPLICIT AND UNINTENTIONAL

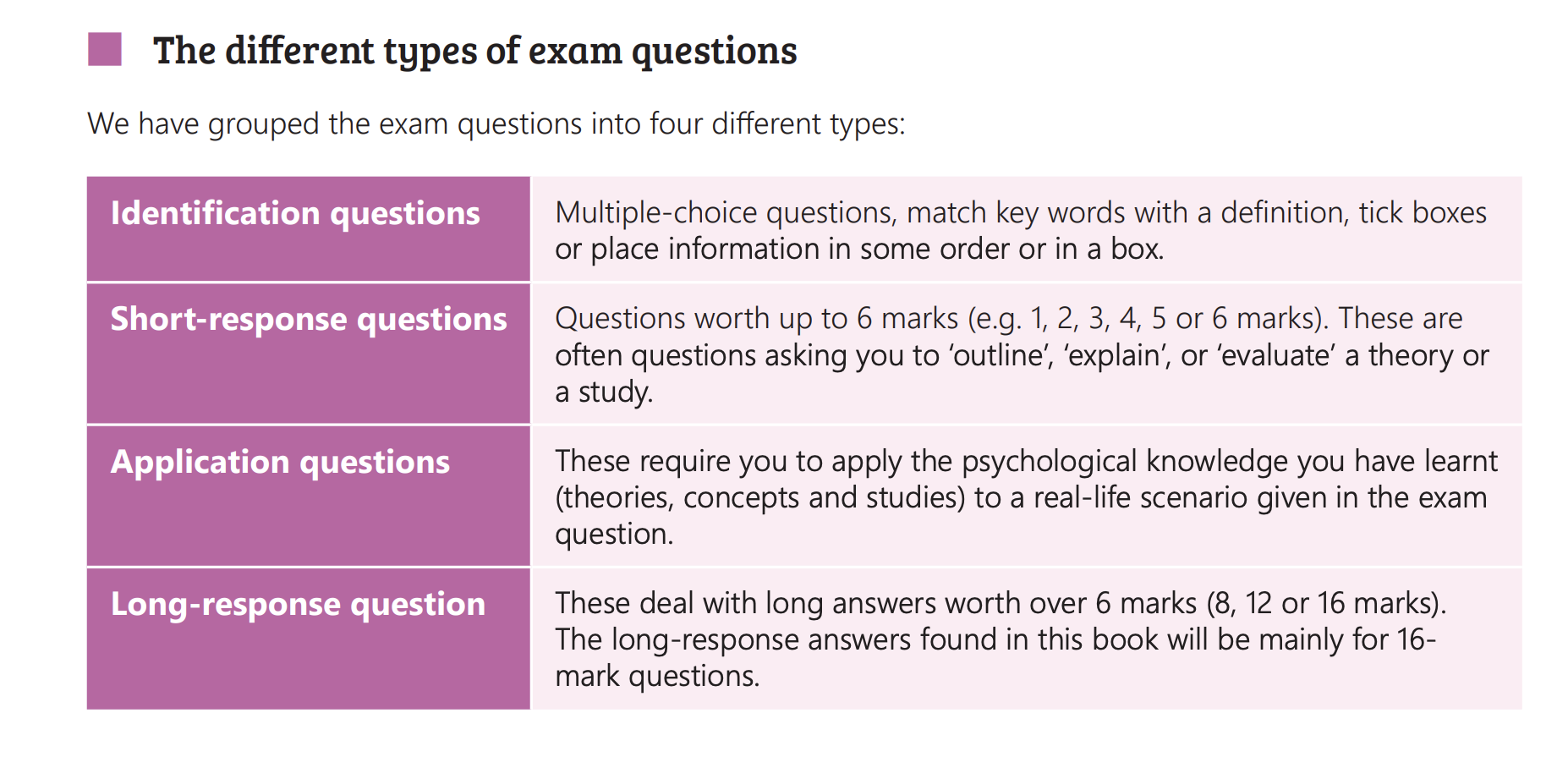

QUESTIONS

MULTIPLE-CHOICE QUESTIONS

Which type of long-term memory involves information that can be consciously recalled and verbally explained? (1 mark)

A Procedural

B Non-declarative

C Declarative

D Implicit

Which of the following is an example of non-declarative memory? (1 mark)

A Knowing the capital of Ghana

B Remembering your last birthday

C Riding a bike

D Recalling items on a shopping list

ODD ONE OUT

Which is the odd one out? (1 mark)

Knowing how to swim

Knowing how to write

Riding a bike

Knowing that Paris is the capital of France

Explain your answer in one sentence. (1 mark)

SHORT QUESTIONS

State one feature of declarative (explicit) memory. (1 mark)

Explain one difference between declarative (explicit) memory and non-declarative (implicit) memory. (2 marks)

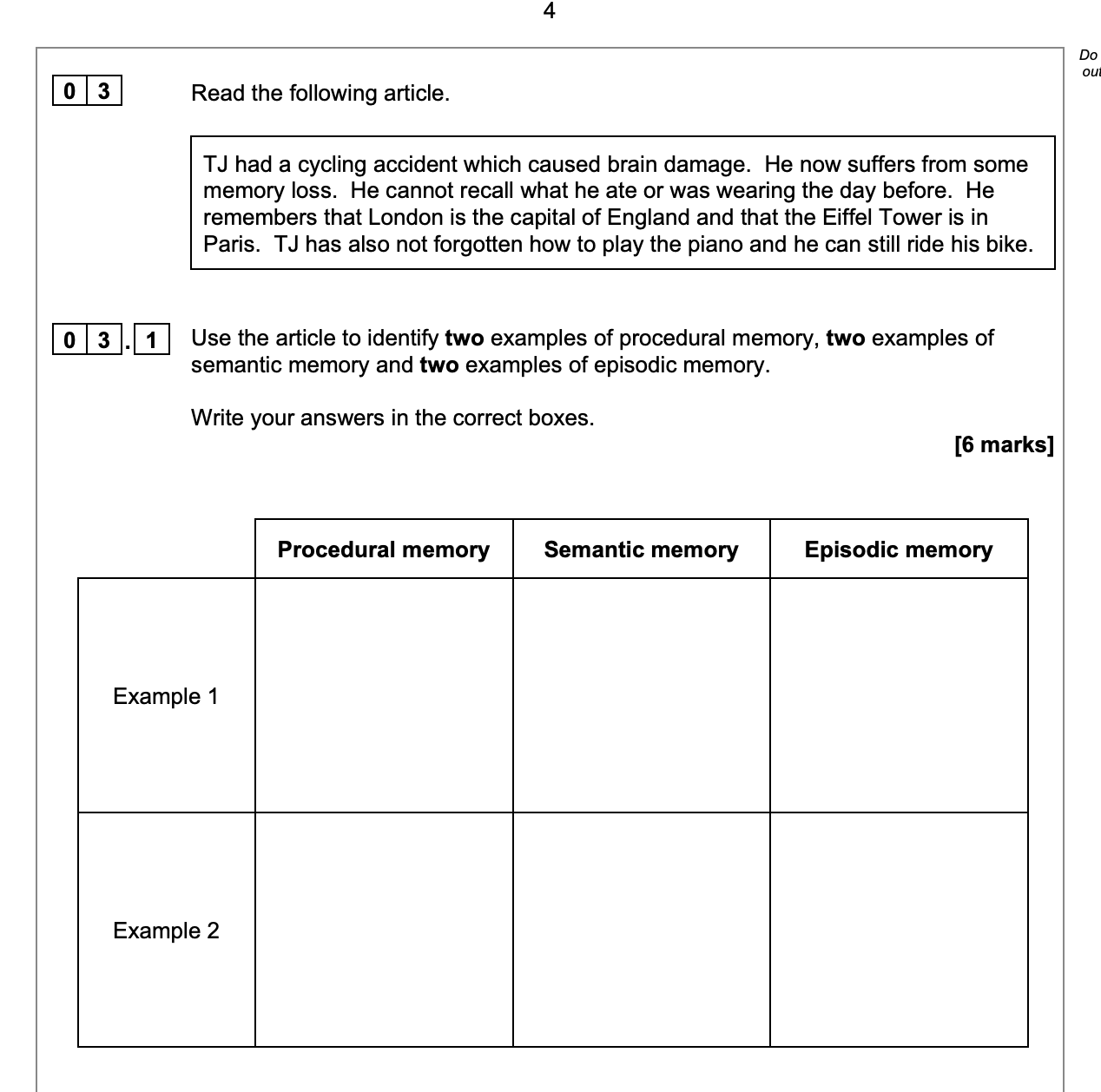

TYPES OF LONG-TERM MEMORY

There are two subtypes of declarative memory:

Semantic memory: Learned information about your environment

Episodic memory (autobiographical memory): Learned information about your life events or experiences

EPISODIC MEMORY, ALSO KNOWN AS AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL

WHAT IT IS:

Episodic memory recalls personal experiences or events, including what happened, where, and when. These memories are tied to specific moments and often include associated emotions and contextual cues.

EXAMPLES:

Remembering your last birthday party.

Recalling the day you passed your driving test.

CHARACTERISTICS:

Autobiographical: Episodic memories are linked to personal experiences.

Time-stamped: They involve a clear sense of when events occurred.

Contextual: These memories include emotions and environmental details.

BRAIN AREAS INVOLVED:

Hippocampus: Critical for forming and consolidating episodic memories.

Prefrontal Cortex: Plays a role in retrieving episodic information

EPISODIC consists of our thoughts or experiences and our recollections of them. Episodic memories are usually based on events in people's lives; however, over time, they move over to Semantic memory as the event’s association diminishes and the memory becomes “knowledge” based. The emotions present during memory encoding determine the strength of episodic memories. Traumatic life events may be recalled more readily due to their strong emotional salience, and episodic memory is believed to help distinguish between imagination and actual events. The brain's prefrontal cortex is linked to the initial encoding of episodic memories and to consolidation and storage processes associated with the neocortex.

SEMANTIC MEMORY

WHAT IT IS:

Semantic memory stores general knowledge and facts about the world. Unlike episodic memory, it is not tied to specific personal experiences, times, or places.

EXAMPLES:

Knowing that Paris is the capital of France.

Understanding the meaning of words like "democracy" or "psychology."

CHARACTERISTICS:

Abstract: Semantic memories are unrelated to particular events or experiences.

Shared: Many people possess the same semantic knowledge.

Timeless: These memories are not linked to specific points in time.

BRAIN AREAS INVOLVED:

Temporal Lobe: The anterior temporal cortex is central to the storage of semantic knowledge.

SEMANTIC MEMORY contains the knowledge, facts, concepts, and meanings the individual has learned, e.g., the capital of France is Paris. Semantic memory may also relate to how particular objects function, their functions, appropriate behaviour in situations, or to abstract concepts such as language or mathematics. The strength of semantic memory is positively correlated with processing strength; semantic memories persist longer than episodic memories. Semantic LTM is linked to episodic LTM; semantic memories are formed from past experiences. Therefore, episodic memory underpins semantic memory, with episodic experiences gradually shifting to semantic memory over time. Semantic coding is primarily associated with the frontal and temporal lobes, with mixed opinions regarding the hippocampus: some argue that the hippocampus is involved, whereas others posit that multiple brain regions contribute.

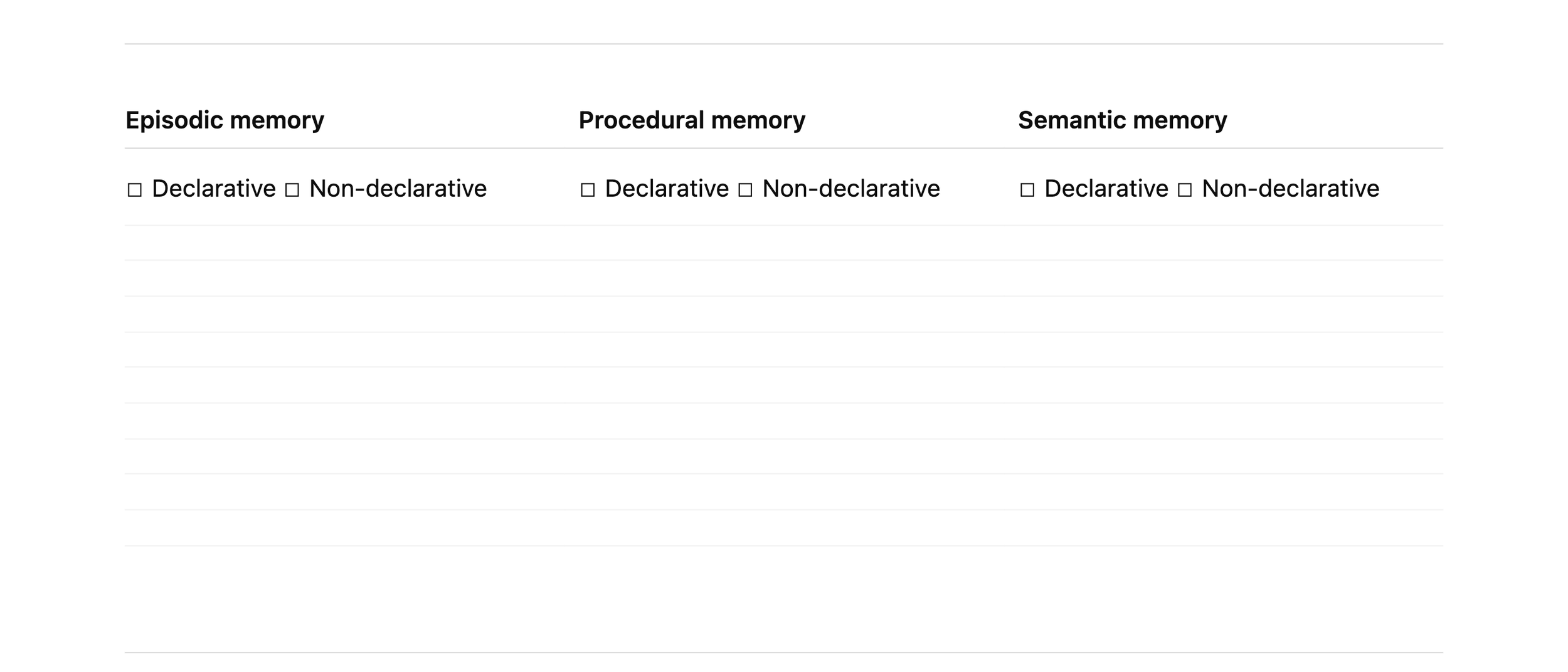

Sort each statement into EPISODIC, SEMANTIC, or PROCEDURAL long-term memory.

Remembering the moment you were told some unexpected news.

Knowing that Paris is the capital of France.

Knowing how to change gears while driving.

Remembering a specific argument you had with someone.

Knowing what the word “justice” means.

Knowing how to keep your balance on a moving bus.

Remembering where you were when you heard about a major news event.

Knowing the rules of a game you have never played.

Knowing how to type quickly on a keyboard.

Remembering a lesson where something suddenly made sense.

Knowing that water freezes at 0°C.

Knowing how to swim.

Remembering a time you felt embarrassed in public.

Knowing what embarrassment is.

Knowing how to hide embarrassment in a social situation.

Remembering a holiday you went on as a child.

Knowing the purpose of a piggy bank.

Knowing how to tie your shoelaces.

Remembering the first time you travelled somewhere on your own.

Knowing where the Eiffel Tower is.

Knowing how to use a contactless card reader.

Remembering a specific conversation from yesterday.

Knowing what a triangle is.

Knowing how to play a simple tune on a piano.

Remembering a birthday celebration.

Knowing who won a major sporting event.

Knowing how to reverse a car into a parking space.

Remembering a time you felt proud of yourself.

Knowing the meaning of a word you learned in school.

Knowing how to brush your teeth

SHORT-ANSWER QUESTIONS

State one characteristic of declarative memory. (1 mark)

State one characteristic of non-declarative memory. (1 mark)

Explain one difference between episodic memory and semantic memory. (2 marks)

Give one example of an episodic memory, one example of a semantic memory and one example of a procedural memory.

Explain one difference between semantic memory and episodic memory. (1 MARK).

Explain one difference between procedural memory and episodic memory. (1 MARK).

Many psychologists believe that there are different types of long-term memory. Describe research into different types of long-term memory. In your answer, refer to what the researchers did and what they found. (6 MARKS).

Kirsty and Helen were discussing a friend who was a renowned guitarist. “Did you hear about Lin-Lin?” said Hyacinth. “She’s had a serious injury to her brain, and now she can’t remember what someone said to her an hour ago. Although apparently she can still play the guitar.” Discuss research into at least two types of long-term memory. Refer to Kirsty and Helen’s conversation in your answer. (4 MARKS).

Psychologists conducted a case study of Patient X, an individual who developed severe amnesia following a car accident. Patient X has difficulty forming new long-term memories, although his short-term memory and memory for events before the accident are unaffected.

The same psychologists conducted experiments with Patient X, who was required to track a rotating disc daily for a week. It was found that Patient X’s performance on the task improved with practice. However, he had no recollection of ever having completed the task and could not recall the names of the psychologists who experimented.

Concerning the experiment involving Patient X, outline two types of long-term memory. (4 MARKS).

Discuss two differences between the types of long-term memory you outlined in your answer to part 1. (4 marks)

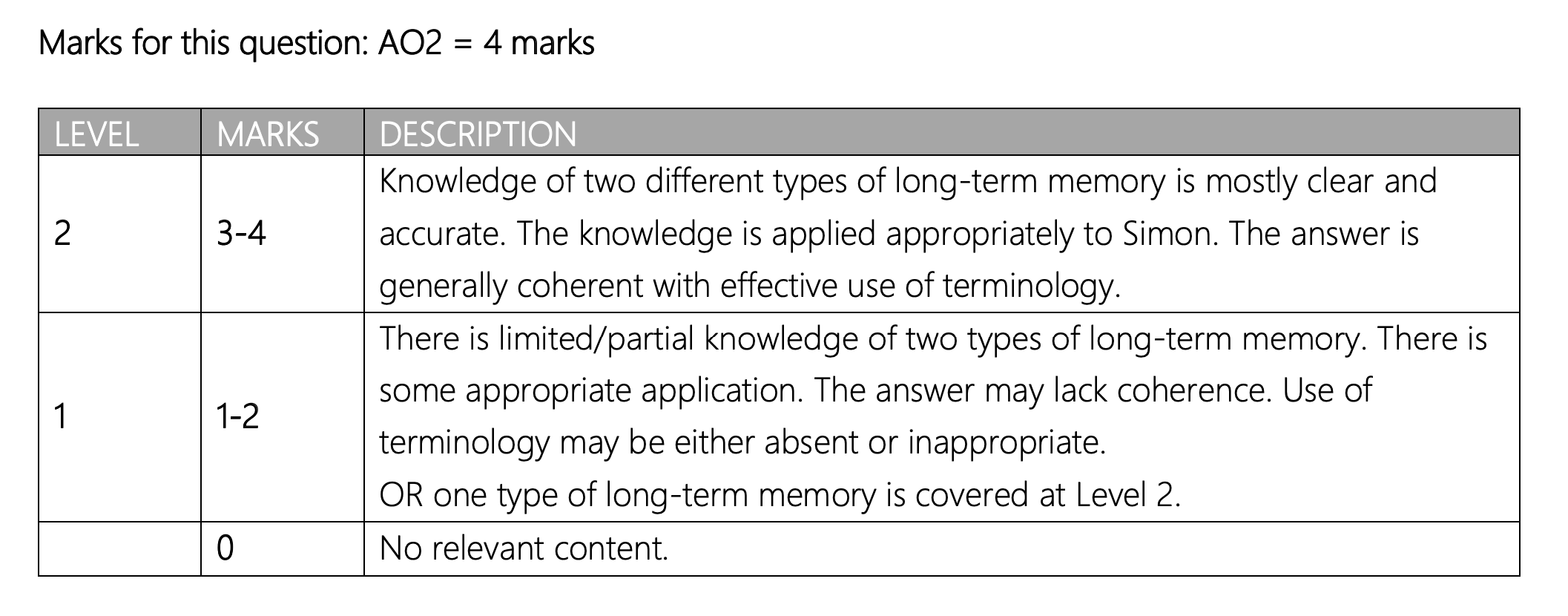

Simon spends the day with his brother. They decide to hire bikes. Although he has not ridden a bike for over 20 years, Simon is surprised to find that as soon as he gets on the bike, he can ride without having to think about it. They go for a long ride and stop off for coffee. While they are in the café, he recognises an old friend from primary school whom he has not seen for many years; they talk about some of the things they did and other people in their class. 5 Referring to Simon’s experiences, outline two different types of long-term memory. (4 marks)

Explain one difference between declarative memory and non-declarative memory. (2 marks)

Give one example of a procedural memory and explain why it is classified as non-declarative. (3 marks)

Explain why people often struggle to verbally describe procedural memories such as riding a bike. (3 marks)

PROCEDURAL MEMORY IN DETAIL

WHAT IT IS:

Procedural memory is the ability to perform tasks and actions without consciously thinking about the steps involved. It is responsible for learning and retaining motor skills, habits, and routines through repetition and practice. Unlike declarative memory, procedural memory operates unconsciously, enabling automatic performance of well-practised activities.

EXAMPLES:

Riding a bike.

Playing a musical instrument, such as the piano.

Typing on a keyboard without looking at the keys.

CHARACTERISTICS:

Implicit: Procedural memory does not require deliberate recall or awareness of the memory process.

Skill-based: It involves motor skills and habits rather than factual or autobiographical knowledge.

Automatic: Once learned, tasks can be performed effortlessly and without conscious thought.

BRAIN AREAS INVOLVED:

Cerebellum: Plays a central role in motor coordination and skill learning.

Basal Ganglia: Critical for habit formation and procedural learning.

Motor Cortex: Involved in executing learned motor activities

PROCEDURAL MEMORY is skill-based memory focused on recalling how to do something, i.e. swimming, reading or cycling and does not require conscious thought. Procedural memories are usually learnt through repetition and practice. Language is believed to be a procedural memory, as it enables individuals to speak with correct grammar and syntax without conscious awareness. Procedural LTM is linked to the neocortex brain areas within the primary motor cortex, cerebellum and prefrontal cortex. This is different from declarative memory stores as they do not rely on the hippocampus to function.

RESEARCH STUDIES ON LOMNG TERM MEMORY

How could PSYCHOLOGISTS TEST WHETHER long-term memory EXISTS AS A DISTINCT phenomenon? Name three methods of research that could be used. Hint: think back to the types of research you have studied on MSM.

How could case studies of brain-damaged patients be used to test whether long-term memory is separate from short-term memory?

How does evidence from patients with selective memory impairment support the existence of long-term memory as a distinct system?

What is the problem with using postmortem studies to study long-term memory?

How could brain scanning techniques be used to test whether long-term memory relies on different brain areas from short-term memory?

How does the use of cognitive neuroscience methods, such as fMRI or PET scans, strengthen conclusions about long-term memory?

How could laboratory experiments be designed to test the duration and capacity of long-term memory?

How does research on very long-term retention provide evidence that long-term memory is more than prolonged short-term rehearsal?

WHERE IS LONG-TERM MEMORY STORED?

All memories are formed in the hippocampus, which is located in the temporal lobes. There are temporal lobes and hippocampi on each side of your head. These parts of your brain sit behind your temples and reach to your ears.

Each type of long-term memory is formed by connecting neurons in various parts of the brain:

Associative learning memory: Amygdala, cerebellum

Declarative memory: Hippocampus

Episodic memory: Hippocampus, temporal lobe, neocortex (cerebral cortex)

Nonassociative learning memory: Reflex pathways (hippocampus)

Nondeclarative memory: Basal ganglia, cerebellum, amygdala

Priming and perceptual memory: Neocortex

Procedural memory: Striatum (forebrain), cerebellum, motor cortex (frontal lobe)

Semantic memory: Temporal cortex (temporal lobe), prefrontal cortex (frontal lobe)

HOW LONG DOES LONG-TERM MEMORY LAST?

There isn’t a specific amount of time that long-term memory can last. In many cases, specific memories can last for years, decades, or even. You may have memories that last a lifetime.

While memories themselves can last indefinitely, your ability to retrieve them from this storage space may not function as well as it once did as you age. This can happen due to natural changes that happen with age — your brain activity slows down, so it might take you a little longer to find specific memories within your archives.

Some conditions and traumatic events, both physical and psychological, can cause memory impairment or long-term memory loss. If you’re having trouble remembering, talk to a healthcare provider

EPISODIC AND SEMANTIC LONG-TERM MEMORY (TULVING, 1972)

Tulving (1972) challenged the view that long-term memory (LTM) is a single, unified store, proposing instead that it comprises distinct subsystems that process different types of information. Earlier models, such as the multi-store model (MSM), treated LTM as a homogenous system, but Tulving argued that this oversimplified the complexity of human memory. His theory gained support from numerous case studies in which individuals with brain damage exhibited impairments in specific aspects of LTM while retaining other forms, providing clear evidence that LTM is not a singular entity. Tulving identified two key types of declarative memory—episodic memory and semantic memory—each serving distinct purposes and characterised by unique functions.

EVALUATION OF TULVING’S MODEL

SUPPORT FOR EPISODIC AND SEMANTIC MEMORY

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE: NEUROIMAGING EVIDENCE

Functional neuroimaging techniques, such as PET and fMRI, reveal distinct activation patterns for episodic and semantic tasks.

Episodic Memory: Activates the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

Semantic Memory: Engages the anterior temporal lobe.

COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY (CASE STUDIES): NEUROIMAGING EVIDENCE

Kent Cochrane (KC): Demonstrated an apparent dissociation between episodic and semantic memory. While KC could recall factual information (semantic memory), he had no recollection of personal experiences (episodic memory), supporting the idea that these are separate systems.

Further support for the separation of semantic and episodic memory comes from Vicari et al. (2007). A case study of a young girl (CL) who suffered brain damage after the removal of a tumour found deficiencies in the ability to create new episodic memories. However, she could still develop semantic memories supporting the theory that they are separate.

Lastly, Clive Wearing had severe episodic memory impairment; he could not remember past autobiographical events in his life. However, he retained semantic knowledge—he could recall factual information, such as the identities of objects, the meanings of words like "son" and "daughter," and general knowledge about the world. This supports the distinction between the two types of declarative memory by demonstrating that, although episodic memory (autobiographical recall) was impaired, semantic memory (general factual knowledge) remained intact, highlighting their independence as separate systems within declarative memory.

Overall, research evidence supports the case for three different LTM stores. Brain scans have shown three distinct areas being active, with the hippocampus and other parts of the temporal lobe, such as the frontal lobe, associated with episodic memory. Semantic memory has been associated with activity in the temporal lobe, whereas procedural memory is associated with the cerebellum and motor cortex.

This supports theories for three distinct stores of long-term memory. Case studies such as HM (Milner 1962) support the case for distinctively different procedural and declarative memory stores. HM could not form episodic or semantic memories due to the destruction of his hippocampus and temporal lobes; however, he could form procedural memory by learning to draw figures by looking at their reflections in a mirror (mirror drawing). However, he could not recollect how he learned this skill, supporting the case for different stores between “knowing how” to do something and semantic knowledge-based or experience-based (episodic) memories.

A weakness of case studies is that they are based on a single individual, making it difficult to generalise the findings to the broader population, as memory deficits may be unique to that person.

TYPES OF LONG-TERM MEMORY EVALUATION

Research evidence supports the case for three different LTM stores. Brain scans have shown three distinct areas being active, with the hippocampus and other parts of the temporal lobe, such as the frontal lobe, associated with episodic memory. Semantic memory has been associated with activity in the temporal lobe, whereas procedural memory is associated with the cerebellum and motor cortex.

This supports theories for three distinct stores of long-term memory. Case studies such as HM (Milner 1962) support the case for distinctively different procedural and declarative memory stores. HM could not form episodic or semantic memories due to the destruction of his hippocampus and temporal lobes; however, he could form procedural memory by learning to draw figures by looking at their reflections in a mirror (mirror drawing). However, he could not recollect how he learned this skill, supporting the case for different stores between “knowing how” to do something and semantic knowledge-based or experience-based (episodic) memories.

A weakness of this study is that it is based on a single individual, making it difficult to generalise the findings to the broader population, as memory deficits may be unique to this individual.

Another major weakness in theories of long-term memory is the lack of research on the brain regions involved in procedural memory. Case studies of individuals with brain damage that affects procedural but not declarative memory are needed to understand this better. However, such cases are sporadic. Therefore, we cannot conclusively say that the procedural memory store is fully understood in any detail to generalise such a theory.

CRITICISMS OF TULVING’S MODEL

The case of Clive Wearing offers another critical insight into long-term memory: Clive could still play the piano, a skill that is neither episodic nor semantic. Playing the piano is an automatic and unconscious skill, not easily articulated or “declared.” For instance, explaining in words how to precisely position your fingers on the keys, how much pressure to apply, or how to seamlessly transition between chords is almost impossible. These actions are deeply ingrained and performed without conscious thought. Despite profound episodic memory impairment, Clive’s ability to play the piano provides compelling evidence for procedural memory as a separate system within long-term memory.

One limitation of Tulving’s 1972 model is its exclusive focus on declarative memory systems (episodic and semantic), neglecting non-declarative memory, such as procedural memory. Procedural memory, which enables skills such as riding a bike or playing an instrument without conscious recall, was formally identified as a long-term memory system in the 1980s by researchers such as Larry Squire.

Although Tulving later acknowledged procedural memory in his subsequent work, its omission from the original model underscores its narrow focus on consciously accessible memories. This reflects an incomplete understanding of the complexity of long-term memory at the time, particularly regarding the role of unconscious memory processes.

INTERDEPENDENCE OF EPISODIC AND SEMANTIC MEMORY

Critics argue that, as Tulving initially proposed, episodic and semantic memory are not independent systems. Instead, there is a dynamic and reciprocal relationship between the two. Semantic knowledge often originates from episodic experiences, with repeated personal encounters contributing to the abstraction of general knowledge. For example, encountering different breeds of dogs over time leads to the semantic understanding of what a "dog" is, including its characteristics and behaviours.

Moreover, episodic memory often relies on semantic knowledge for context and meaning. For instance, recalling a specific childhood visit to a zoo might draw on semantic information about the types of animals present or the general concept of a zoo. This interdependence blurs the boundaries between the systems and raises questions about whether they function as entirely distinct processes.

Neuroimaging evidence supports this interplay, showing overlapping brain regions involved in episodic and semantic tasks. While the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex are more active in episodic recall, the anterior temporal lobe—a region associated with semantic memory—frequently engages in episodic tasks. This overlap challenges the strict separation proposed by Tulving and highlights the interconnectedness of memory processes.

The interdependence also has practical implications for memory impairments. For example, conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, which primarily affects episodic memory in its early stages, can eventually lead to semantic memory deficits as the disease progresses. This progression underscores how the systems interact and depend on one another for optimal functioning.

While Tulving's distinction between episodic and semantic memory was groundbreaking, the evidence for their interdependence suggests that they are not entirely discrete. Instead, they represent interconnected facets of a broader memory system that work together to support learning, recall, and the construction of meaning in human cognition.

APPLICATIONS TO REAL LIFE

APPLICATIONS IN DIAGNOSIS AND EDUCATION

Tulving’s distinction between episodic and semantic memory has had profound implications for understanding and diagnosing memory-related conditions. For instance, Alzheimer’s disease often begins with impairments in episodic memory. Patients may struggle to recall recent events, such as forgetting conversations or losing track of daily activities. In contrast, their semantic memory (general knowledge, such as recognising objects or knowing the meaning of words) may initially remain intact. This pattern is consistent with Tulving’s model, which identifies episodic and semantic memory as separate systems.

In contrast, semantic dementia, a form of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), primarily affects semantic memory. Patients with this condition lose knowledge of facts and concepts. For example, they may forget the names of everyday objects, such as calling a "dog" an "animal," or be unable to identify familiar landmarks, even while their episodic memory remains relatively preserved in the early stages. These distinct patterns of memory loss support the validity of Tulving’s distinction between episodic and semantic memory systems and demonstrate their relevance in clinical settings.

In education, the distinction has informed strategies for memory enhancement. For example, focusing on episodic memory might involve creating vivid, personal learning experiences, such as storytelling or real-life applications, to aid recall. Conversely, teaching methods aimed at semantic memory often rely on repetition and the organisation of facts to strengthen general knowledge. Understanding these differences allows educators to tailor techniques to the type of memory they wish to enhance.

DIAGNOSING SEN AND BEHAVIOURAL CONDITIONS THROUGH MEMORY IMPAIRMENTS

EPISODIC MEMORY IMPAIRMENTS

AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER (ASD)

Individuals with ASD often struggle with recalling autobiographical events, which affects their ability to form coherent narratives or imagine future scenarios.

POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD)

Episodic memories can become fragmented or intrusive, with individuals vividly recalling sensory details of trauma but failing to construct coherent narratives.

ATTENTION DEFICIT HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER (ADHD)

People with ADHD may exhibit impairments in episodic memory due to difficulties with attention and working memory, which affect their ability to recall specific past events.

SEMANTIC MEMORY IMPAIRMENTS

DEVELOPMENTAL LANGUAGE DISORDER (DLD)

DLD can involve deficits in the recall and use of factual knowledge, such as word meanings, which impact language acquisition and communication.

DYSLEXIA

Some individuals with dyslexia may exhibit weaknesses in semantic memory, struggling to retain word meanings or general knowledge, which can exacerbate reading comprehension difficulties.

OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER (OCD)

Semantic memory impairments may arise in OCD, particularly with difficulties in categorising and recalling general knowledge due to overreliance on repetitive thought patterns.

LONG-TERM-MEMORY QUESTIONS

Give one example of an episodic memory, one example of a semantic memory and one example of a procedural memory.

Explain one difference between semantic memory and episodic memory. (1 MARK).

Explain one difference between procedural memory and episodic memory. (1 MARK).

Many psychologists believe that there are different types of long-term memory. Describe research into different types of long-term memory. In your answer, refer to what the researchers did and what they found. (6 MARKS).

Kirsty and Helen were discussing a friend who was a renowned guitarist. “Did you hear about Lin-Lin?” said Hyacinth. “She’s had a serious injury to her brain, and now she can’t remember what someone said to her an hour ago. Although apparently she can still play the guitar.” Discuss research into at least two types of long-term memory. Refer to Kirsty and Helen’s conversation in your answer. (4 MARKS).

Psychologists conducted a case study of Patient X, an individual who developed severe amnesia following a car accident. Patient X has difficulty forming new long-term memories, although his short-term memory and memory for events before the accident are unaffected.

The same psychologists conducted experiments with Patient X, who was required to track a rotating disc daily for a week. It was found that Patient X’s performance on the task improved with practice. However, he had no recollection of ever having completed the task and could not recall the names of the psychologists who experimented.

Concerning the experiment involving Patient X, outline two types of long-term memory. (4 MARKS).

Discuss two differences between the types of long-term memory you outlined in your answer to part 1. (4 marks)

7. Simon spends the day with his brother. They decide to hire bikes. Although he has not ridden a bike for over 20 years, Simon is surprised to find that as soon as he gets on the bike, he can ride without having to think about it. They go for a long ride and stop off for coffee. While they are in the café, he recognises an old friend from primary school whom he has not seen for many years; they talk about some of the things they did and other people in their class. 5 Referring to Simon’s experiences, outline two different types of long-term memory. (4 marks)

POSSIBLE APPLICATION:

Episodic memory is a form of explicit memory that includes personal experiences (episodes), such as Simon and his friend recalling events from school.

Episodic memories must be retrieved consciously and with effort; therefore, Simon’s conversation with his friend will have helped him recall the information.

Episodic memories comprise several elements (e.g., people and places) that are interwoven to form a single memory. This means that discussing what they did at school will help Simon remember more information.

Procedural memory is a type of implicit memory that includes the ability to perform specific tasks, actions, or skills, such as Simon remembering how to ride his bike. Simon’s skill for riding a bike will have become ‘automatic’.

Procedural memories are often acquired through repetition and practice early in life, and when Simon was a child, he spent a long time practising how to ride his bike. h Procedural memories do not need to be retrieved consciously, which is why Simon did not need to think about how to ride the bike. Credit other relevant applications