COGNITIVE

WHY YOU NEED TO KNOW THIS FROM THE OUTSET

SPECIFICATION: The cognitive approach: the study of internal mental processes, the role of schema, and the use of theoretical and computer models to explain and make inferences about mental processes. The emergence of cognitive neuroscience

BACKGROUND TO THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

The earliest major approach was the psychodynamic perspective, which argued that unconscious processes shaped by early experience influence behaviour. It highlighted the depth and complexity of human motivation, but was criticised for lacking scientific testability.

Behaviourism followed as a deliberate rejection of psychoanalytic ideas. By focusing only on observable behaviour, it introduced rigorous experimental methods and helped establish psychology as an empirical discipline. However, its insistence on studying only what can be measured created two key limitations: it overlooked internal mental processes and could not fully explain human cognition, language or reasoning. In other words, it can explain how behaviour is changed by reinforcement and punishment, but not the internal structure of thinking or how behaviour is generated, because it refuses to model the internal system that produces it

BIRTH OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

While behaviourism remains relevant—especially for understanding how reinforcement, punishment and associative learning shape behaviour—it accounts for only part of human experience. Its focus on the environment cannot explain the higher cognitive capacities that distinguish human thought.

The limits of behaviourism led directly to the rise of the cognitive approach. This perspective set out to examine the processes behaviourism ignored: how we attend to information, store it, retrieve it, use language, recognise faces, make decisions and remain conscious of our own thinking. In other words, it neglects what goes on in the brain. The Cognitive Revolution began in the mid-1950s, when researchers across several fields developed theories of mind grounded in complex representations and computational analogies (Miller, 1956; Broadbent, 1958; Chomsky, 1959; Newell, Shaw, & Simon, 1958). The cognitive approach investigates the mechanisms underlying behaviour, asking what we do, why we do it and how mental activity is generated.

THE COGNITIVE APPROACH: OPENING THE "BLACK BOX"

Cognitive psychologists believe understanding "what goes on inside the mind" is key to making sense of human behaviour. They focus on the mental processes that shape our actions and thoughts, looking beyond observable behaviours to explore the mind's inner workings.

The cognitive approach emerged as a response to the limitations of behaviourism, which dominated psychology in the early 20th century. Behaviourists like B.F. Skinner insisted that studying mental processes was futile since they couldn’t be observed or measured. They treated the mind as a "black box"—an unknown and unknowable space—arguing that all behaviour could be explained through environmental stimuli and responses. For behaviourists, the focus was on observable actions rather than on the invisible processes that drive them.

Cognitive psychologists challenged this view, arguing that the mind isn’t a mysterious black box but an intricate and essential part of understanding behaviour. They recognised that humans aren’t just passive responders to the environment but active information processors. This approach opened the door to exploring how we think, learn, remember, and make decisions.

DOES THE COGNITIVE APPROACH REPLACE BEHAVIOURISM?

While the cognitive approach focuses on investigating internal mental processes, this does not mean behaviourism is no longer relevant. Cognitive psychology and behaviourism have distinct focuses and methodologies, but complement rather than replace one another.

Cognitive psychology prioritises understanding how we process, store, and retrieve information, exploring concepts like memory, perception, and problem-solving. However, it does not dismiss the importance of learning from the environment—a cornerstone of behaviourism. Instead, it provides a broader perspective by incorporating how internal processes interact with external stimuli to shape behaviour.

WHY DOES THE COGNITIVE APPROACH MATTER?

The cognitive approach has profoundly impacted psychology, influencing everything from education to artificial intelligence. It helps explain how we process and use information, why we remember some things but forget others, and how we solve problems or make decisions. Significantly, it shifted the focus of psychology back to the mind, showing that human behaviour can’t be fully understood without exploring the internal processes that guide it.

By opening up the "black box," cognitive psychology has provided a richer, more nuanced understanding of what it means to think, learn, and be human. It reminds us that the mind isn’t just a passive recipient of the world but an active participant in creating our reality.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COGNITIVE PSNEUROSCIENCE AND NEUROSCIENCE

A “BRAIN IN LOVE”? BUT WHICH FIELD USES SCANS LIKE THIS — COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE OR NEUROSCIENCE?

FIND OUT BELOW

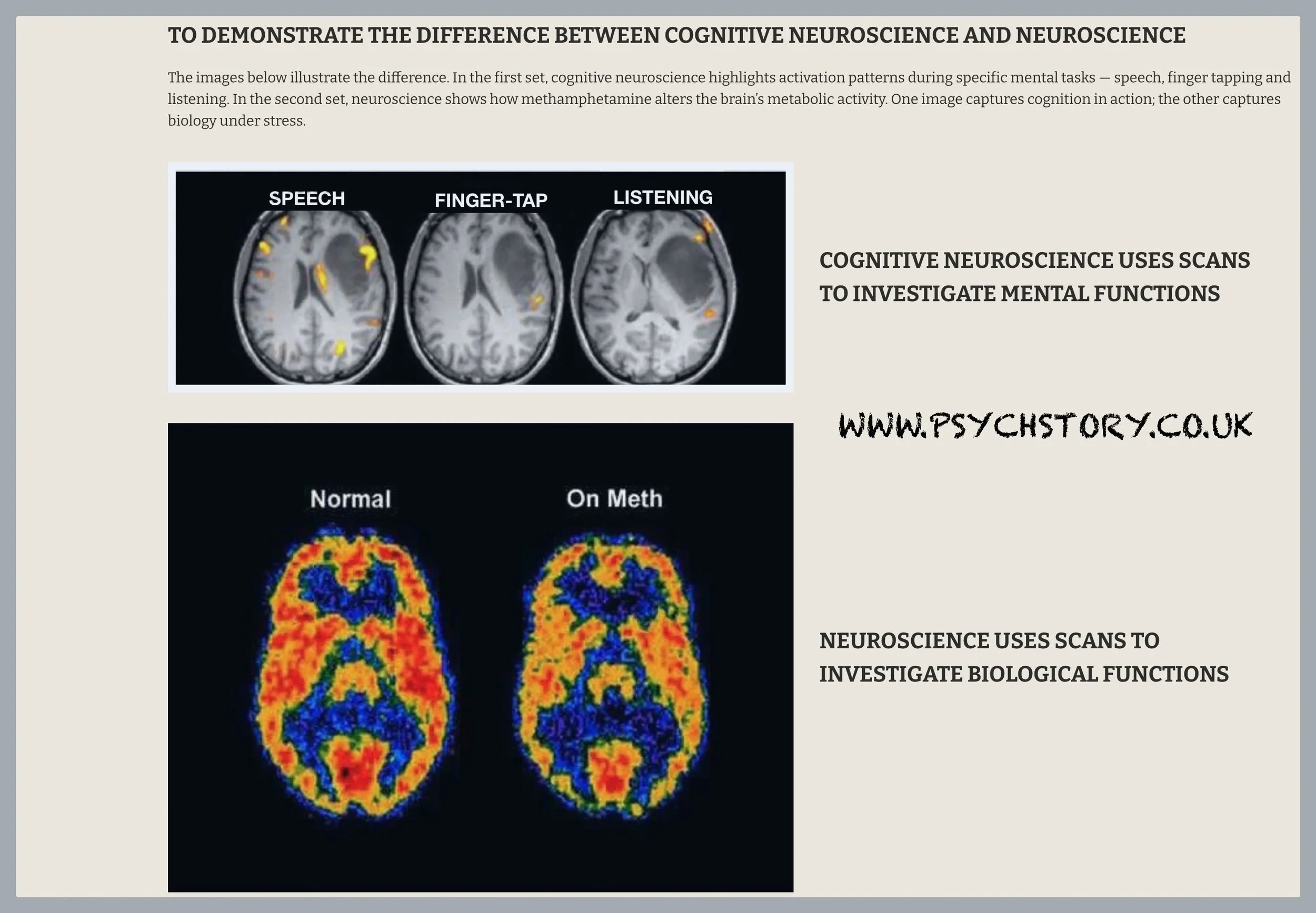

Cognitive neuroscience and neuroscience both use brain imaging techniques, but they do not study the same phenomena. Cognitive neuroscience uses imaging techniques to investigate mental functions, including brain activity during speaking, listening, memory, finger tapping, and other cognitive operations. The goal is to understand the neural implementation of mental processes — which regions activate, in what sequence, and how different networks coordinate during a task.

Neuroscience, by contrast, is concerned with the biological mechanisms that give rise to behaviour and psychopathology. It studies hormones, neurotransmitters, neural circuits, and brain structures; how these are altered by injury, drugs, disease, or experience; and how plastic the system is over time. When it uses scans, it is typically to examine metabolism, blood flow, structural damage or connectivity changes that underlie disorders such as addiction, dementia or depression, rather than to map the fine-grained structure of particular cognitive operations.

The two fields are complementary. Cognitive neuroscience links mental processes to neural activity. Neuroscience explains the biological conditions that support or disrupt those processes. They employ similar tools but address different questions.

TO DEMONSTRATE THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE AND NEUROSCIENCE

The image below illustrate the difference. In the first set, cognitive neuroscience highlights activation patterns during specific mental tasks — speech, finger tapping and listening. In the second set, neuroscience shows how methamphetamine alters the brain’s metabolic activity. One image captures cognition in action; the other captures biology under stress.

KEY ASSUMPTIONS OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

The approach rests on three core assumptions about how the mind works:

INTERNAL MENTAL PROCESSES (BLACK BOX )

Cognitive psychologists argue that thinking, memory, attention, language and decision-making can and should be studied scientifically, even though they cannot be observed directly.THE MIND–AS–COMPUTER METAPHOR (INFORMATION PROCESSING)

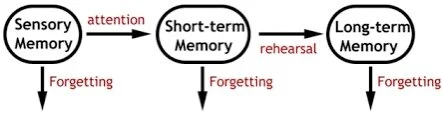

Human cognition is treated as an information-processing system: it receives input, transforms it, stores it, and produces output. This metaphor is not taken literally, but it is used to model how mental processes might be organised.THEORETICAL MODELS

Because mental processes are hidden, psychologists develop models (e.g., the multi-store model) that decompose these processes into components. These models are then tested and refined through research.

THE MIND AS COMPUTER METAPHOR

THE MIND-AS-COMPUTER METAPHOR

The mind-as-computer metaphor is a central idea within cognitive psychology. It frames the mind as an information-processing system whose operations can be understood by analogy with a computer. Importantly, not all cognitive psychologists accept the metaphor literally. Some treat it simply as a modelling tool that helps explain mental processes, whereas others argue that, in functional terms, human cognition is computational.

According to this view, both humans and computers rely on structured, rule-governed systems. They encode information, store it, manipulate it, and generate output. Both use networks of associations to organise knowledge: computers through data structures and algorithms, humans through semantic networks. The point is not that computers “think like humans”, but that many operations humans perform are computational in nature.

The metaphor emphasises that cognition follows fixed procedures rather than free-floating intuition. Human behaviour depends on the state of the underlying system. If memory circuits are damaged, memory fails. If perceptual mechanisms are disrupted, perception fails. In that sense, humans behave like “wet robots”: a metaphor for a biological organism whose thoughts and actions are determined by the functioning of their physical architecture.

Of course, computers lack emotions, but this is a matter of evolutionary design, not a conceptual impossibility. Emotions evolved to support survival and sexual reproduction; a machine that was never shaped by natural selection would not possess such mechanisms. The metaphor, therefore, remains helpful in highlighting the structural similarities between computational systems and human cognition, without claiming that the two are identical in every respect.

The mind-as-computer metaphor does not explain everything — especially the social, emotional and embodied aspects of human experience — but it remains one of the most influential frameworks for understanding how information is processed, stored and used in the human mind.

WHAT SYSTEMS DOES THE COGNITIVE APPROACH STUDY?

Cognitive psychologists study internal processes such as:

MEMORY: How we store, retrieve, and use information over time.

ATTENTION: How do we focus on certain stimuli while ignoring others?

PERCEPTION: How we interpret sensory information to understand our environment.

LANGUAGE AND SPEECH: How we communicate ideas and interpret meaning.

PROBLEM-SOLVING AND PLANNING: How we think ahead and find solutions to challenges.

FACE RECOGNITION: Identifying and remembering individual faces is a key skill in social interaction.

SELF-AWARENESS AND SELF-RECOGNITION: How we perceive ourselves as unique individuals.

CONSCIOUSNESS: The broader awareness of our thoughts, surroundings, and existence.

THEORETICAL MODELS

In cognitive psychology, a theoretical model is simply a way of explaining how the mind works by breaking complex processes—such as memory—into smaller, understandable parts. Because psychologists cannot open the brain and observe thinking or memory unfold in real time, they construct models to determine what the “components” of a system might be and how they function.

For example, a central question in memory research is whether memory is a unitary system (a single store with no distinction between short-term and long-term memory) or a multi-component system in which STM and LTM are separate and function differently. Models help to answer questions such as:

• How do the components interact?

• What happens to the system if one part is damaged?

• How does one cognitive system—such as memory—interact with others, such as language, attention, or perception?

These models are not literal pictures of the brain. They are simplified diagrams or descriptions that illustrate what occurs within the mind and in what order. For students, they serve as a map, clarifying processes that would otherwise be invisible.

THE MULTI-STORE MODEL OF MEMORY

UNDERSTANDING BRAIN SYSTEMS THROUGH THEORETICAL MODELS

Cognitive systems function as networks and never operate in isolation. , with each component interacting with others to perform complex tasks. For example:

A good theoretical model asks questions such as:

What is the system? For example, is the system being studied memory, attention, or perception?

What are the components of the system? In the case of memory, these might include short-term memory, long-term memory, and sensory memory.

How does the system work? For instance, how does attention select crucial sensory information and ensure it is temporarily stored in short-term memory?

How does the system interact with other systems? For example, how does memory work with language systems, such as Broca's area, to retrieve and structure words for communication?

EXAMPLE 1: READING A BOOK

Reading a book involves several interconnected systems working together:

Perception: The visual cortex processes written text, identifying letters and words.

Language Systems: Wernicke’s area decodes the meaning of the words, while Broca’s area constructs an internal dialogue or vocalises the text.

Memory: Semantic memory retrieves the meanings of words while working memory holds the sentence structure to make sense of the text as a whole.

Attention: Maintains focus on the text, filtering out distractions like background noise.

This seamless integration of systems allows us to understand complex narratives and retain information.

EXAMPLE 2: SPEAKING AND BROCA'S AREA

Language production highlights the interaction between systems, particularly the role of Broca’s area in coordinating speech. Consider answering a question in conversation:

Attention: Focuses on the speaker’s question, ignoring irrelevant sounds.

Perception: Processes the auditory input in the auditory cortex, then Wernicke’s area interprets the question’s meaning.

Memory: Long-term memory retrieves relevant vocabulary and grammar rules for the response.

Broca’s Area: Organises the retrieved words into a grammatically correct sentence.

Motor Systems: The motor cortex activates the tongue, lips, and vocal cords to articulate the response.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A SYSTEM IS DAMAGED?

When Broca’s area is damaged, it leads to Broca’s aphasia, a condition where speech production is impaired. Individuals with Broca’s aphasia:

Have difficulty forming complete sentences, often speaking in broken or fragmented phrases.

Can still understand language, as Wernicke’s area remains functional.

Highlight the importance of Broca’s area within the broader language system.

WHY MODELS MATTER

Theoretical models enable cognitive psychologists to examine how different systems interact, providing insights into both normal and impaired cognition. These models help us understand the intricate mechanisms underlying human behaviour and cognition by decomposing complex processes such as reading and speaking.

Although these interactions seem automatic, theoretical models slow them down, decompose the components, and show how they fit together. This helps psychologists investigate the processes scientifically and clarifies what the mind is doing “behind the scenes” during even the simplest behaviours.

RESEARCH METHODS USED IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

THEORETICAL MODELS AND TESTING

Behaviourism had insisted that the mind could not be studied because it could not be observed. The brain was treated as a black box: psychologists could only measure what went in and what came out (i.e., stimuli and responses). Psychoanalysis made the opposite claim: the workings of the mind could be accessed, but only through the therapist’s interpretation of the unconscious. Neither approach provided a scientific means of examining the internal processes underlying thinking, memory, or language.

Given that cognitive psychologists study the “black box”, the obvious question is how they investigate something the behaviourists claimed could not be opened. In other words, how do they explore the holy of holies — thought itself?.

Cognitive psychologists in the 1960s sought to understand what the brain was doing between input and output, but they faced a practical obstacle: they could not observe the living brain. As a result, they had to rely on the tools available at the time – experiments, behavioural tasks, case studies of brain injury, memory errors, and laboratory manipulations that allowed them to infer the structure of mental processes indirectly.

As technology advanced, the discipline advanced with it. Developments in computer science have introduced new ways of modelling how information is processed, stored, and retrieved. Later, medical imaging techniques (such as CT, PET and eventually fMRI) made it possible to observe the activity of healthy and damaged brains in real time, giving psychologists a biological window into systems that previously had to be inferred.

Against this background, the four core research methods of cognitive psychology developed and remain central today. They reflect the historical progression from “we cannot see inside the brain” to “we can now measure its activity”, while preserving the original aim of understanding the internal processes that produce human behaviour.

The defining feature of science is that every theoretical claim must be tested empirically.

Cognitive psychologists begin the research process by proposing a theoretical model to explain a mental process. Early models were based on observations from post-mortems and, to some extent, logical reasoning, but cognitive psychology does not stop at theorising in the way earlier philosophers did. The next step is to test the model scientifically.

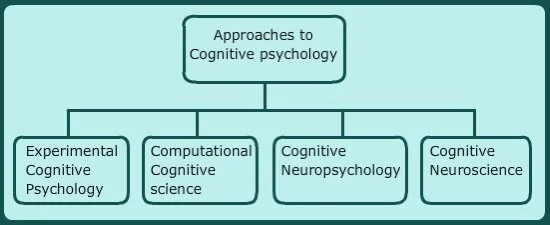

Cognitive psychologists employ four primary research methods to investigate how the brain processes mental functions:

Cognitive neuropsychology:

Experimental cognitive psychology

Cognitive neuroscience

Cognitive science

All research methods in cognitive psychology share the same objective: to uncover the underlying principles of internal mental processes. The only difference between these domains is how they investigate their theories.

THE FOUR RESEARCH DOMAINS

THE FOUR RESEARCH METHODS IN DETAIL

COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY:

Cognitive neuropsychology has its roots in the 1800s, long before it became a formally recognised approach. Cognitive neuropsychology studies people with brain damage to deduce how the neurotypical brain works. Examples of cognitive neuropsychology include KF, HM, Phineas Gage, Paul Broca, Clive Wearing, Charles Whitman, and many more. For instance, Paul Broca famously linked speech production to a specific brain area by studying patients with language deficits and confirming the damage through post-mortem analysis. Similarly, cases like Phineas Gage revealed how frontal lobe injuries could alter personality and decision-making.

Before modern scanning technologies, researchers relied on post-mortem examinations, waiting until patients with brain injuries had passed away to examine their brains for damage. During the patients’ lifetimes, psychologists gathered clues through careful observation and clinical interviews, piecing together how specific injuries affected behaviour and cognition.

Today, with advanced neuroimaging techniques such as MRI and CT scans, cognitive neuropsychologists can study brain damage in living patients with greater precision. These technologies allow researchers to map cognitive deficits to specific brain regions without waiting for postmortem confirmation, facilitating understanding of how brain regions interact to support cognitive functions.

Cognitive neuropsychology remains a vital tool for exploring how the brain operates.

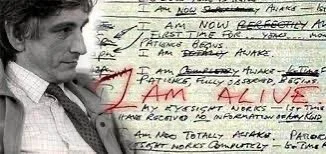

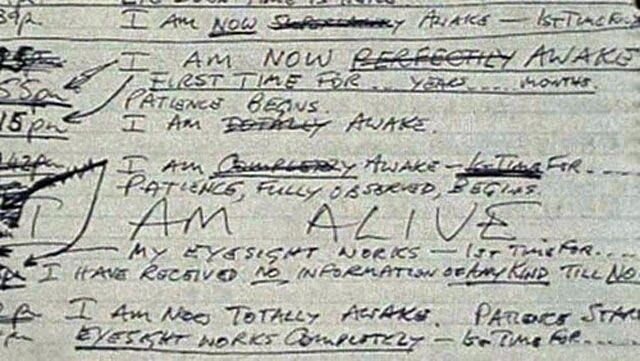

CLIVE WEARING AN AMNESIAC WITH NO ABILITY TO FORM NEW MEMORIES, FREQUENTLY BELIEVED THAT HE HAD ONLY RECENTLY AWOKEN FROM A COMATOSE STATE

EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY

Cognitive neuropsychology has been essential in shaping our understanding of how the mind is organised, but its methods face significant limitations. The weaknesses differ depending on whether the data come from post-mortem examination or modern brain-scanning, and some problems affect both approaches.

LIMITATIONS OF POST-MORTEM EVIDENCE

Postmortem research laid the foundations of cognitive neuropsychology (e.g., Broca, Wernicke, HM), but it is constrained..

RECOVERY AND REORGANISATION COMPLICATE INTERPRETATION

After damage, the brain often reorganises. Improvements or preserved abilities may reflect compensation rather than the original cognitive architecture. This makes it challenging to infer “normal” functioning from abnormal systems.

INFERENTIAL, NOT DIRECT

The method identifies what is impaired and what is preserved, but cannot observe the mental process itself. All conclusions about cognitive structure are indirect, based on reasoning from patterns of deficit rather than on direct observation of the internal mechanisms.

LIMITED FOR HIGHER COGNITION

Complex abilities such as reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving depend on widely distributed networks. Focal lesions rarely cleanly disrupt these systems, so neuropsychology struggles to isolate their component processes.

NO REAL-TIME COGNITIVE STRUCTURE

Even with modern imaging, cognitive neuropsychology cannot reveal how mental operations are structured: representational formats, decision rules, sequencing of internal transformations, or coding preferences. Scans can show activation, not the architecture of thought.

LIMITATIONS OF NEUROIMAGING (FMRI, PET, EEG)

Scanning overcame many limitations of post-mortem studies, allowing researchers to study living brains during tasks; however, it has its own constraints.

Scans show activity, not structure.

A scan can show where activity increases and sometimes when, but it cannot reveal the mechanisms of thought. It cannot tell us the format of memory, the rules used to make decisions, or the steps involved in understanding language. Activation does not equal explanation.

Imprecise for studying complex cognition

Higher processes such as reasoning, decision-making or planning rely on widespread networks. Because many regions activate together, scans cannot cleanly separate the components of these abilities.

Interpretation is inferential

Researchers must guess which mental process is operating when an area “lights up”. These inferences can be erroneous and often depend on the researcher's assumptions.

For example, a scan cannot reveal what a chimpanzee or human understands during a language task; it merely shows that certain regions are active.

Technical limits

Even modern imaging has constraints on temporal resolution (EEG is fast but has low temporal resolution, whereas fMRI is clear but slow). This makes it difficult to chart the fine-grained sequence of cognitive operations.

LIMITATIONS SHARED BY BOTH METHODS

LIMITED GENERALISABILITY

Findings are based on single cases or tiny samples. Because brain organisation varies substantially between individuals, especially after injury, the pattern observed in one patient (e.g. HM, KF, Tan) may not reflect the typical structure of cognition.

Individual brains differ

Damage, age, plasticity and natural variations mean that no two brains are organised in the same way. A pattern seen in one patient may not reflect the typical cognitive architecture.

Inferring the normal from the abnormal

This is the central conceptual problem. Cognitive neuropsychology seeks to elucidate how the healthy mind functions by observing what happens when the system is damaged. But damaged brains do not behave like “healthy brains minus one component”; they are altered systems with distortions, compensations and loss of function. This weakens the causal conclusions drawn from deficits.

Higher cognition is distributed.

Most complex human abilities do not reside in single brain regions. Both post-mortems and scans struggle to isolate their components because multiple areas contribute simultaneously.

WHY THESE LIMITATIONS MATTER

Even today, neuropsychological evidence must be interpreted cautiously.

It is valuable for identifying which brain areas are involved, but it cannot fully reveal:

• how cognitive processes are structured

• what internal rules they follow

• how representations are stored or transformed

• how one operation flows into the next

These insights come primarily from experimental cognitive psychology, which measures behaviour directly.

Neuropsychology helps map cognition onto the brain, but experiments remain necessary for discovering the architecture of the mind

.

EXPERIMENTAL COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Experimental cognitive psychology is the part of the cognitive approach that treats mental processes as testable systems. Its ethos is simple: if a process exists — attention, memory, decision-making, perception — then it should produce clear, measurable behavioural patterns when systematically manipulated. The aim is to uncover the functional architecture of the mind by observing how performance changes when specific demands are added, removed or interfered with. It is the discipline that maps the “rules of thought” by treating cognition as something that can be experimentally probed rather than guessed at, intuited, or interpreted

The experimental method was the primary approach in cognitive psychology before the advent of cognitive neuroscience. Emerging in the 1950s, when technology lacked the sophistication for direct brain analysis.

Cognitive psychology relies heavily on experimental cognitive methods. Researchers design experiments to test how people process information under different conditions. Most of these studies are laboratory experiments in which variables can be tightly controlled and measured with precision. To a lesser extent, cognitive psychologists also use field and natural experiments, but the laboratory remains the primary setting because it allows more precise measurement and, ultimately, replication.

The logic is the same for any experiment:

Propose a theory

Design an experiment

Collect data under controlled conditions

Determine whether the model’s predictions are supported

This scientific cycle—model, test, refine—distinguishes cognitive psychology from earlier introspective or interpretative traditions. It ensures that claims about thinking, memory, perception or language are grounded in evidence rather than speculation. It is important to note, however, that although behaviourism refused to study internal mental processes, the scientific method it employed was no less rigorous than that used in cognitive research.

. The scientific nature of this process has been critical in advancing our understanding of human cognition.

NOTABLE EXPERIMENTS IN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Many foundational studies in cognitive psychology highlight the experimental method’s strength:

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) developed the working memory model, proposing components such as the phonological loop and the episodic buffer.

Loftus and Palmer (1974) explored how leading questions distort memory recall in eyewitness testimony.

Miller (1956) proposed the "magic number seven," identifying the limited capacity of short-term memory.

Peterson and Peterson (1959) demonstrated the rapid decay of information in short-term memory without rehearsal.

Bartlett (1932): Investigated reconstructive memory using “The War of the Ghosts,” showing how cultural schemata influence recall.

Piaget (1936): Examined cognitive development in children, providing a framework for understanding learning stages.

EVALUATION OF EXPERIMENTAL COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

Experimental cognitive psychology remains essential because it reveals properties of mental processing that neither neuroimaging nor cognitive science models can access.

Neuroimaging can show which brain regions activate, the order in which they activate, and the relative metabolic demand of different structures during a task. It can also demonstrate that particular cognitive operations recruit multiple regions simultaneously. What it cannot reveal is the structure of the mental operation itself: the representational format, the internal decision rules, the capacity limits, the interference patterns, the coding preferences, or the transformations that occur between input and output. These must be inferred from behaviour, and behaviour is what experiments measure directly.

Similarly, computational models in cognitive science can simulate aspects of memory, language or reasoning, but they cannot confirm that human cognition actually uses the same internal procedures. They provide possible architectures, not evidence of the real one.

Laboratory experiments fill this gap. They can:

• identify functional components such as separate stores or subsystems

• measure capacity limits (e.g. digit span, working memory load)

• reveal processing constraints such as attentional bottlenecks

• demonstrate interference effects (proactive, retroactive, articulatory suppression)

• distinguish encoding formats (acoustic versus semantic)

• map serial-position patterns and forgetting curves

• show how performance changes when a specific process is taxed or removed

These properties cannot be extracted from fMRI scans or computational simulations.

LIMITATIONS

EXTERNAL VALIDITY

Laboratory tasks often lack ecological realism. A digit-span test or word-list recall rarely resembles real-world memory use.

POPULATION VALIDITY

Many studies rely on narrow, WEIRD samples (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic). Findings may be culturally biased.

NO DIRECT BIOLOGICAL ACCOUNT

Experiments show what the cognitive system does, but not how the brain implements it. This limitation led to the development of cognitive neuroscience.

Despite these issues, the experimental approach remains the foundation of cognitive psychology. It identifies the functional architecture of cognition, which neuroscience maps onto the brain and computational science models. Without laboratory data, both of those fields would have no validated cognitive structure to interpret

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

Cognitive neuroscience primarily focuses on studying the biological processes underlying cognition in neurotypical individuals, aiming to map mental processes to specific brain regions and pathways. In essence, it explores the biological basis of cognitive psychology, using advanced technologies to determine where and when these processes occur in the brain.

Methods Used in Cognitive Neuroscience:

Functional neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI and PET are used to observe which brain regions are active during specific cognitive tasks.

Electrophysiology: Using EEG to measure electrical activity in the brain and track rapid changes in neural function.

Experimental Psychology: Employing tasks and stimuli to link mental processes with brain activity.

Cognitive Genomics and Behavioural Genetics: Investigating how genetic factors influence brain function and cognitive abilities.

These methods allow cognitive neuroscientists to study processes such as memory, language, attention, and perception in individuals with typical brain function, providing a baseline for understanding cognition.

EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

While cognitive neuroscience has provided groundbreaking insights, it also has limitations:

Focus on Neurotypical Individuals: Primarily studying individuals without brain injuries or disorders may overlook cognitive variations attributable to atypical brain function.

Poor Spatial or Temporal Resolution: Some techniques struggle to capture fine details of brain activity or measure changes in real time.

Limited Behavioural Scope: Imaging techniques may not fully capture complex or nuanced behaviours.

Participant Discomfort: Scanning methods like fMRI require participants to remain still in enclosed spaces, which can be uncomfortable or unnatural.

Contemporary cognitive neuroscience increasingly relies on the brain to explain the workings of the human mind, most notably through the rise of neuroimaging. The method has received mixed reactions. Classical cognitive scientists from the experimental and computational traditions argue that neuroimaging cannot answer the central questions about the mechanisms that produce intelligent behaviour. A scan can show where activity occurs, but not how mental processes are structured. Researchers must therefore infer cognitive mechanisms from patterns of neural activity, and those inferences can be biased or overly speculative.

For example, Savage-Rumbaugh studied sign acquisition in the bonobo Kanzi. Neuroimaging could show which brain areas were active, but it could not reveal what Kanzi understood or how he represented meaning. This illustrates the fundamental limitation: neuroimaging can reveal the neural basis of cognition, but not the content or structure of thought itself.

As a result, some researchers still distinguish between the two fields. Cognitive psychology focuses on information processing and behaviour; cognitive neuroscience focuses on the biological systems that underlie these processes.

Others, however, see them as increasingly integrated. Richard Ivry of UC Berkeley argues that cognitive neuroscience is not simply “neuroscience applied to cognition” but an integration of four traditions—experimental psychology, computational modelling, cognitive theory, and neuroscience—whose emphasis remains on understanding mental functions. On this view, the aim is to model mental behaviour in a way that resembles the biological mind, not to reduce cognition to biology alone.

Despite its limitations, cognitive neuroscience is a cornerstone of modern psychology, offering a biological lens to understand how neurotypical brains support complex mental processes.

COGNITIVE COMPUTER SCIENCE:

Cognitive computer science examines how mental processes can be described, modelled and tested using computational principles. It concerns the algorithmic, representational, and information-processing aspects of cognition. This includes how humans encode and store information, how knowledge is structured, how decisions are made, how language is understood, and how learning occurs over time.

The aim is to develop computational models that exhibit behaviours that resemble human cognition. These models do not claim to replicate the biological brain, but they provide a formal way to test hypotheses about how complex mental processes might be organised. By constructing artificial systems capable of tasks such as problem-solving, pattern recognition, memory retrieval, or language processing, researchers can explore the kinds of representations and rules required for a cognitive system to function.

Cognitive computer science, therefore, sits at the intersection of psychology, computer science and artificial intelligence. It treats cognition as a set of operations that can, in principle, be described algorithmically, allowing researchers to compare natural cognition with artificial systems and to explore both their similarities and their limits.

EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

STRENGTHS

Provides explicit, testable models

Computational models force psychologists to specify their assumptions clearly.

A theory of memory, attention, or decision-making must be written as rules, algorithms, or representational structures that can be executed. This moves cognitive theory away from vague description and toward precise, falsifiable predictions.

Reveals what is possible for a cognitive system

By building an artificial system that performs a task in a human-like way, researchers can explore the types of representations and processes a mind could use.

This allows the discovery of new mechanisms that might never have been proposed through introspection or behavioural data alone.

Bridges psychology, AI and neuroscience

Cognitive computer science sits at the intersection of disciplines.

It allows direct comparison between:

natural cognition (humans and animals)

artificial cognition (computer models)

neural implementation (via cognitive neuroscience)

This makes it one of the most integrative strands of the cognitive approach.

Offers powerful tools for simulating disorders

By altering a computational model, researchers can simulate cognitive impairments seen in amnesia, dyslexia, decision-making deficits, schizophrenia or language disorders.

This helps generate hypotheses about what underlying mechanisms might be failing.

WEAKNESSES

Models may not reflect how humans actually think

A computer model can successfully perform a task without using the same internal operations as the human mind.

A simulation that resembles human behaviour does not necessarily reveal the real cognitive architecture.

No guarantee of biological plausibility

Many computational systems solve problems through methods human brains could not use:

unlimited memory

perfect precision

parallel operations, humans do not possess

This creates a gap between algorithmic success and cognitive realism.

Overemphasis on rule-based, linear processing

Some models assume cognition is sequential and algorithmic.

But human thought often involves intuition, emotion, heuristics and pattern-based reasoning that do not map neatly onto computer procedures.

Behavioural equivalence ≠ , cognitive equivalence

A model may match human output while relying on radically different internal mechanisms.

This limits the confidence with which researchers can infer the mental processes underlying behaviour.

OVERALL

Cognitive computer science is invaluable for generating theories about how mental processes might be organised, and for testing them with precision that ordinary behavioural methods cannot achieve.

However, it cannot, on its own, reveal the mechanisms by which the human mind operates.

It provides possible architectures, not definitive ones, and must be interpreted in light of experimental data and neuroscience.

SUMMARY

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY AND A COGNITIVE RESEARCH METHOD?

Students often assume that cognitive psychology, experimental cognitive psychology and cognitive neuroscience are separate approaches.

This is incorrect. There is one cognitive approach, but it contains multiple sub-disciplines, each studying cognition from a different angle.

The same sub-disciplines also function as research methods, which is why the terminology can be confusing.

This is the correct framework.

EXPERIMENTAL COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY

What it is:

The umbrella discipline that studies how the mind processes information, including memory, perception, attention, language, reasoning, and decision-making.

How it does this:

Primarily through experimental cognitive psychology – controlled behavioural experiments that infer mental processes from performance.

Why it matters:

It identifies how cognitive systems work (capacity limits, encoding types, bottlenecks, serial position effects).

It does not measure the brain.

It measures behaviour and infers the processes behind it.

COGNITIVE NEUROPSYCHOLOGY

What it is:

A sub-discipline that studies people with brain damage to infer which parts of the brain support which cognitive functions.

How it works:

Historically through:

• post-mortems, then (from the 1990s onward) CT, MRI and EEG

• case studies of patients such as HM, KF, Broca’s “Tan”

• comparing preserved versus impaired functions

What it reveals:

The functional architecture of cognition:

Which components are separable, which survive damage, and which fail together?

It is both a method and a sub-discipline.

COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE

What it is:

A modern sub-discipline that examines cognition using brain-scanning technologies (fMRI, PET, EEG).

What it reveals:

• where cognitive processes take place

• the sequence in which they activate

• the metabolic demand of a task

• differences between healthy and pathological brains

What it cannot reveal:

• representational formats

• encoding rules

• decision algorithms

• the internal structure of a mental operation

Those must come from behavioural experiments.

It is both a sub-discipline and a research method.

COGNITIVE SCIENCE / COMPUTATIONAL MODELLING

What it is:

A cross-disciplinary field (psychology, AI, computer science, linguistics, philosophy) that builds computational models of cognition.

What it does:

Simulates processes such as:

• memory encoding

• problem-solving

• language comprehension

• visual recognition

What it reveals:

• possible architectures the mind could use

• algorithms capable of reproducing human behaviour

What it cannot reveal:

• whether humans actually use those algorithms

• whether the model corresponds to brain implementation

Again, it is both a method and a sub-discipline

WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO UNDERSTAND

The cognitive approach is the parent.

The four subdisciplines are children with different methods.

All four are also research methods.

This is why textbooks use the terms interchangeably.Only by combining them can we fully understand cognition.

Experiments reveal the structure.

Neuroscience reveals the implementation.

Neuropsychology reveals dissociations.

AI reveals possible mechanisms.

CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

STUDYING A FISH OUT OF WATER HAS NO EXTERNAL VALIDITY

MUNDAME REALISM AND ECOLOGICAL VALIDITY

Many criticisms of cognitive psychology focus on the methods used in laboratory experiments, particularly the use of contrived tasks that bear little resemblance to everyday behaviour. Classic memory studies often ask participants to recall artificial materials such as nonsense trigrams or meaningless digit sequences—stimuli people rarely encounter outside the laboratory. These designs raise concerns regarding external validity, particularly regarding mundane realism.

However, a lack of mundane realism does not automatically imply a lack of ecological validity. An experiment can use artificial materials and still produce findings that generalise to real-world cognition if the underlying process being studied operates in the same way outside the laboratory. Indeed, although short-term memory research often uses nonsense syllables, converging evidence from field studies, naturalistic observations, and applied settings confirms the same pattern: sensory memory lasts 1–2 seconds, and short-term memory lasts approximately 18 seconds. The artificiality of the task does not necessarily invalidate the reality of the mechanism.

TRIANGULATION

Ultimately, cognitive psychology does not rely solely on laboratory experiments. It draws on a range of additional research methods—cognitive neuroscience, cognitive neuropsychology, and cognitive computer science—each of which uses rigorous procedures for collecting and evaluating evidence. This diversity of methods is a significant strength of the cognitive approach because it triangulates findings and counters the common critique that laboratory studies are “artificial”.

Although each research domain has its own limitations (see above), its findings converge to produce robust conclusions. For example, Baddeley’s dual-task research was supported by neuropsychological evidence from brain-damaged patients such as HM and KF, and further validated through neuroimaging studies using PET scanning. When behavioural, clinical, and biological evidence all point in the same direction, the explanatory power of the theory is significantly strengthened.

Overall, the cognitive sciences are held in high regard within the scientific community for their empirical rigour and use of multiple, complementary research strategies.

THE MIND AS COMPUTER METAPHOR

A further evaluation concerns the mind–as–computer metaphor. Some critics argue that the analogy oversimplifies human cognition because computers and biological organisms appear fundamentally different. They point out that humans make errors, forget, retrieve incorrect information, are influenced by emotion, hormones, fatigue and life events. In contrast, computers fail only when hardware is damaged or code is faulty. On this basis, critics claim that modelling cognition on a computer-like system lacks validity because it does not capture the organic, emotional or evolutionary complexity of the human mind.

However, this criticism misunderstands the purpose of the metaphor. No cognitive psychologist claims that the evolution of artificial intelligence mirrors the evolution of Homo sapiens, nor that computers require the exact emotional mechanisms humans evolved for reproductive success. Humans evolved cognitive systems for survival, cooperation and sexual selection; machines did not. The absence of emotions in a computer is therefore expected, not evidence against computational modelling.

The real point of the metaphor is structural, not biological. Cognitive psychologists argue that intelligence, memory and language may rely on information-processing procedures that are computational in nature, even if the medium differs (silicon vs neurons). A system can lack emotions yet still process syntax, infer rules, update representations, generate output, or solve problems in ways that closely resemble human reasoning. In this sense, computational modelling offers a valid and robust framework for describing the architecture of cognition, even if the embodiment differs radically.

Thus, the criticism that “humans are emotional, computers are not” does not undermine the metaphor. It simply highlights that different evolutionary pressures produce different systems, yet both systems may still instantiate similar computational principles

ARE WE MORE THAN THIS?

REDUCTIONISM

The cognitive approach is often criticised for reductionism. By focusing on information-processing mechanisms, it explains behaviour primarily in terms of internal mental operations such as attention, memory, heuristics or theory of mind. In doing so, it inevitably brackets off other determinants of behaviour, including biological, social, developmental and emotional processes. As a result, cognitive explanations, while precise, are rarely complete.

For example, Baron-Cohen’s work on autism framed the condition as a deficit in theory of mind and investigated this through cognitive tests such as the Sally–Anne task. However, this perspective overlooked alternative contributors, including prenatal hormone exposure, genetic variations, sensory-processing differences and social-environmental factors. His account offered an elegant cognitive mechanism, but one that did not encompass the full complexity of autistic development.

More broadly, cognitive models seldom incorporate:

• Biological variables such as neurotransmitters, hormones, neural circuitry or brain maturation

• Emotional and motivational states, despite their apparent influence on perception, decision-making and memory

• Social context, including parenting, attachment, culture, and communication practices

• Developmental trajectories, which shape how cognitive systems emerge and change over time

This reductionism is not a flaw in method but a limitation in scope. Cognitive psychology produces valuable insights, but only by isolating cognitive mechanisms from the wider biological and social systems in which they operate. A complete account of behaviour requires integrating these layers rather than treating cognition as the sole driver.

IMPRISONED OR FREE?

SOFT DETERMINISM

The cognitive approach in psychology is often described as adopting a soft-determinist (or compatibilist) stance in the free will-determinism debate. It recognises that behaviour is influenced by prior causes—including biological factors, environmental influences, developmental experiences, and internal mental processes—while maintaining that individuals retain a degree of reflective, intentional control over their actions. Decisions are neither wholly random nor uncaused, yet people are not merely passive responders to external stimuli.

The cognitive system incorporates processes such as evaluation, deliberation, planning, and goal-setting, which generate the subjective sense of agency and choice. These processes, however, function within inherent limitations imposed by the brain's architecture, including attentional constraints, memory systems, cognitive biases, and susceptibility to emotional or stress-related influences.

From this viewpoint, behaviour remains causally determined yet can still be purposeful, reasoned, and self-directed.

Cognitive psychologists reject the idea of absolute, unconstrained free will. Instead, they emphasise that human action occurs within the boundaries set by our cognitive framework. Illustrative examples include:

An individual may aim to focus attention, but working memory capacity limits simultaneous processing of information.

A person might strive for rational decision-making, but heuristics and biases—such as confirmation bias, the availability heuristic, or anchoring—systematically distort judgment.

Someone may intend to exercise self-control (e.g., by delaying gratification), but success depends on factors such as prefrontal cortex efficiency, prior learning experiences, and neurochemical processes involving dopamine.

In these instances, actions feel voluntary, yet the cognitive architecture defines the feasible range of outcomes.

Soft determinism thus avoids extremes: it dismisses the binary view of humans as either entirely autonomous agents or mere mechanistic products of biology and environment. Agency emerges within a deterministic framework—people can reflect, plan, and adapt their behaviour, but only through the mental resources shaped by evolution, development, and experience.

This perspective aligns closely with key empirical insights from cognitive psychology, including:

Decision-making frequently begins at a preconscious level, with conscious awareness emerging subsequently (as suggested by neuroscience studies of readiness potentials).

Attention can shift automatically in response to threats, overriding deliberate control.

Memory is reconstructive and prone to errors, rather than a perfectly controllable retrieval system.

Executive functions enable adaptability and flexibility, though their effectiveness is constrained and differs between individuals.

The cognitive approach, therefore, affirms the phenomenological experience of choice while attributing it to underlying deterministic mechanisms that operate primarily outside conscious awareness.

In essence, the cognitive approach supports a compatibilist position (often termed soft determinism in educational contexts): individuals behave intentionally, but those intentions are both generated and limited by the structured operations of the cognitive system. This balanced view underpins practical applications, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, where people actively restructure thoughts despite inherent constraints.

On the plus side, this view is refreshing because, apart from humanism, the other psychological approaches are hard determinism, which is a depressing and fatalistic view of life. At least a soft determinist view recognises that individuals still play a role in causation and can be blamed or praised for their behaviour. On the negative side, hard determinists criticise cognitive psychologists for failing to realise the extent to which freedom is limited. They also point out that it is difficult to draw a line on what is and isn’t a determining factor in human choices. Moreover, is it determinism if it allows freedom?

B.F. Skinner criticised the cognitive approach as he believed that only external stimulus-response behaviour could be scientifically measured. More importantly, he thought the mediation processes between stimulus and response, e.g., the black box, did not exist and were thus irrelevant. Paradoxically, recent research in cognitive neuroscience has shown that the human brain makes up its mind up to 10 seconds before an individual is cognisant of a decision. Neuroimaging of participants making decisions revealed that researchers could predict which choice participants would make before the subjects were even aware they had made a decision. So perhaps Skinner and the other early behaviourists were right, after all, and maybe the blackbox isn’t that relevant.

It should be noted that this finding does not mean that studying mental processes is no longer important; it simply indicates that consciousness may not be as valuable as early cognitive psychologists thought.

APPLICATIONS TO THE REAL WORLD

When applied to psychopathology, the cognitive approach explains dysfunctional behaviour as a consequence of disruptions within standard information-processing systems. Under typical conditions, perception, attention, interpretation and memory operate together to construct a stable, organised representation of events. When any of these components malfunctions—for example, by focusing attention too narrowly, interpreting neutral events as negative, or retrieving memories in a biased manner—the resulting thought patterns become distorted because the underlying processing has been altered. “Faulty thinking”, therefore, refers to errors within the cognitive system itself, not a separate category of irrationality.

This pattern is clearly demonstrated in conditions such as depression and anxiety, where attentional biases towards threat, a tendency to select negative interpretations, and skewed recall of past events create a self-reinforcing cognitive loop. These distortions arise from the same components that usually support accurate reasoning; what changes is the way the system filters, selects and combines information.

COGNITIVE BEHAVIOUR PSYCHOLOGY

CBT follows directly from this information-processing view. It assumes that although cognition is shaped by biological and environmental causes, aspects of the system can be adjusted through structured practice. By identifying automatic thoughts, examining the assumptions that drive them, and rehearsing alternative interpretations, CBT attempts to recalibrate the processing biases that maintain the disorder. Its success in conditions such as depression and anxiety (Hollon & Beck, 1994) illustrates how modifying the operation of a cognitive system can alter emotional outcomes and behaviour.

When applied to psychopathology, the cognitive approach explains dysfunctional behaviour as a consequence of disruptions within standard information-processing systems. Under typical conditions, perception, attention, interpretation and memory operate together to construct a stable, organised representation of events. When any of these components malfunctions—for example, by focusing attention too narrowly, interpreting neutral events as negative, or retrieving memories in a biased manner—the resulting thought patterns become distorted because the underlying processing has been altered. “Faulty thinking”, therefore, refers to errors within the cognitive system itself, not a separate category of irrationality.

This pattern is clearly demonstrated in conditions such as depression and anxiety, where attentional biases towards threat, a tendency to select negative interpretations, and skewed recall of past events create a self-reinforcing cognitive loop. These distortions arise from the same components that usually support accurate reasoning; what changes is the way the system filters, selects and combines information.

CBT follows directly from this information-processing view. It assumes that although cognition is shaped by biological and environmental causes, aspects of the system can be adjusted through structured practice. By identifying automatic thoughts, examining the assumptions that drive them, and rehearsing alternative interpretations, CBT attempts to recalibrate the processing biases that maintain the disorder. Its success in conditions such as depression and anxiety (Hollon & Beck, 1994) illustrates how modifying the operation of a cognitive system can alter emotional outcomes and behaviour.

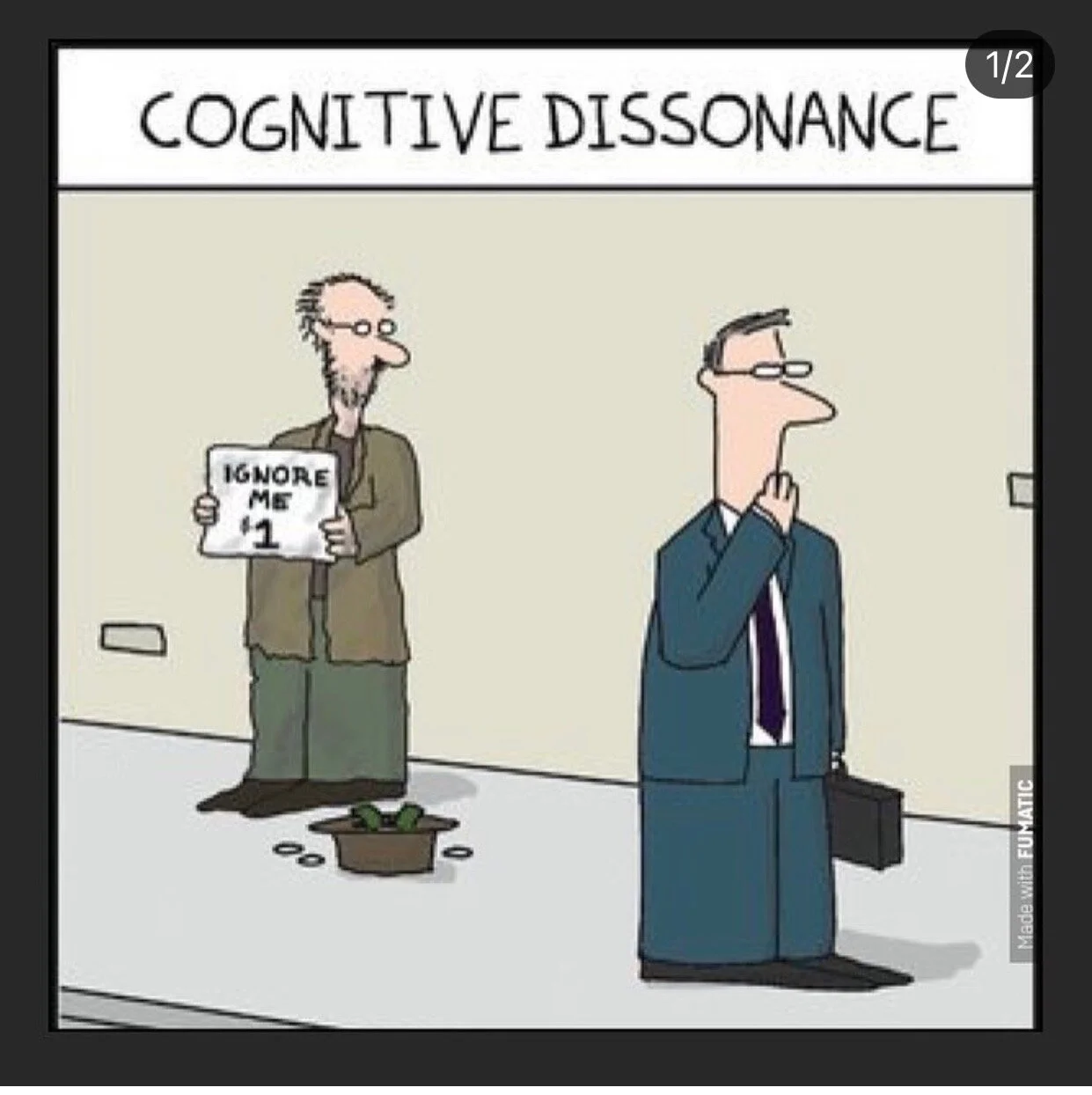

Cognitive dissonance is a theory that refers to the mental conflict that occurs when a person's behaviour and beliefs do not match

OTHER APPLICATIONS

The cognitive approach has also had a vast practical influence across domains such as childcare, education, and forensic interviewing. By analysing how attention, memory, and interpretation operate in real situations, cognitive research has shown how easily information processing can be distorted by context or questioning. For example, Loftus and Palmer’s work demonstrated that a witness’s memory is not a fixed record but a reconstructive process that integrates new information with existing representations. Leading questions, therefore, alter the witness’s memory trace by modifying how the event is encoded or retrieved. This insight reshaped police interviewing practices, emphasising neutral questioning and procedures such as the cognitive interview to support more accurate recall. Similar principles apply in education, where understanding spacing, retrieval practice, and processing depth has improved teaching strategies, and in childcare, where research on attention, perception and early memory development has informed methods for assessing what young children understand and how their recall can be supported without suggestion.

STEREOTYPES CAN BE CHALLENGED WHEN YOU UNDERSTAND SCHEMA THEORY

DISCOVERIES

DISCOVERIES: SCHEMATA, STEREOTYPES AND HEURISTICS

One of the most influential contributions of the cognitive approach is the identification of schemata—organised knowledge structures that guide perception, memory and interpretation. Schemata allow the mind to process vast amounts of information efficiently by providing ready-made frameworks for recognising patterns, predicting outcomes and filling in missing details. However, the exact mechanisms that make cognition efficient also introduce systematic distortions. Schemata can become rigid, biased, or overly generalised, giving rise to stereotypes: simplified, often inaccurate assumptions applied to individuals or groups. Cognitive psychologists have also demonstrated that people frequently use heuristics—mental shortcuts that reduce cognitive load but lead to predictable errors in judgment. Examples include the availability heuristic (judging likelihood from ease of recall) and the representativeness heuristic (judging category membership by similarity rather than probability). These discoveries revealed that human cognition is both powerful and fallible: it enables rapid processing but is prone to systematic bias. They also provided a foundation for modern research into prejudice, decision-making, memory distortion and clinical disorders, illustrating how everyday reasoning can be shaped—and sometimes distorted—by the underlying architecture of the cognitive system.

THE COGNITIVE APPROACH IS NOT LIKE THE OTHER APPROACHES

Lastly, the cognitive approach differs from the other major approaches in psychology because it does not offer a unified account of the causes of behaviour. Approaches such as the biological, psychodynamic, or behaviourist models make explicit causal claims—about genes, unconscious conflict, or reinforcement histories—about why people behave as they do. Cognitive psychology does not attempt to locate a single origin of behaviour. Instead, it aims to describe the functional architecture of the mind: how information is perceived, encoded, stored, transformed and used. In that sense, it explains the mechanisms through which causes operate, rather than providing the causes themselves. The cognitive system is the “hardware” through which biological, social, and developmental influences must pass; it does not, by itself, subscribe to a nature-or-nurture position.

This becomes clear when considering its treatments. Beyond cognitive-behavioural therapies and techniques aimed at improving cognitive control or brain plasticity, the cognitive approach offers relatively few standalone interventions. Modifying thought patterns targets only one component of the system; many conditions require additional biological or environmental change. The strength of the cognitive approach is therefore not its ability to operate in isolation, but its capacity to integrate with other explanatory frameworks.

This integrative quality is evident across disciplines. Social learning theory relies on cognitive processes—attention, retention, and decision rules—to explain how behaviour is acquired. Evolutionary psychology depends on cognitive architectures shaped by natural selection. Neuroscience identifies the neural implementation of cognitive functions. Artificial intelligence models borrow representational formats and problem-solving strategies from human cognition. In each case, cognition provides the organising framework through which other causal theories operate. Rather than competing with the other approaches, the cognitive approach functions as the bridge that links them, offering a shared language for understanding how information is processed, interpreted and used to guide behaviour.