WHAT IS PSYCHOLOGY

BUSTING PSYCHOLOGY MYTHS

NOT ALL IN YOUR HEAD

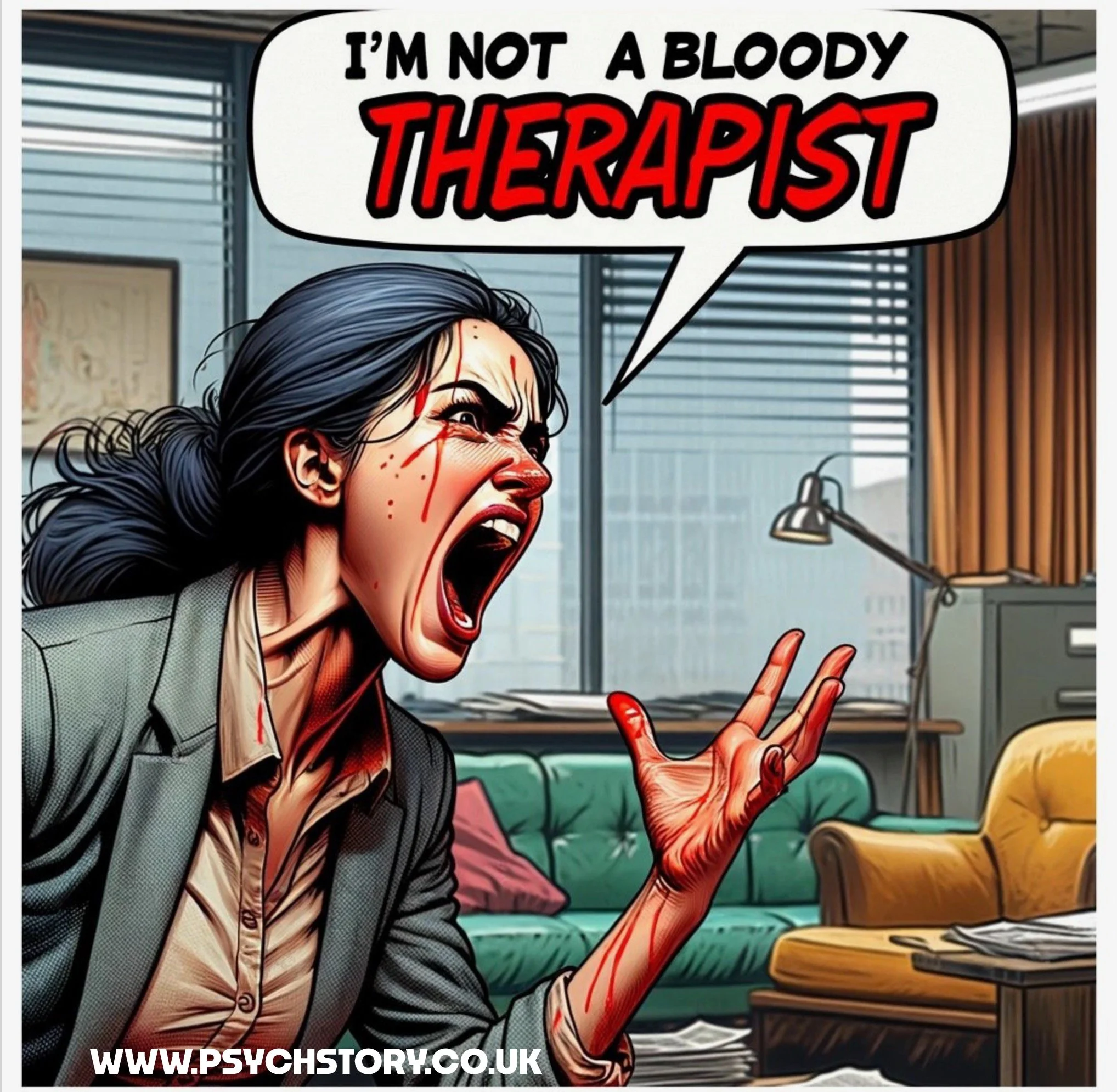

Psychology is one of those subjects everyone thinks they understand—until they actually study it. Ruined by pop culture, self-help books, and pub conversations, the field has accumulated more myths than a Greek tragedy. This article strips away the stereotypes and takes aim at some of the most persistent misconceptions.

Psychology has a strange reputation: respected as a science, yet riddled with caricatures. Mention you study it at a party and someone will ask if you’re reading their mind. Others assume you spend your time unlocking childhood trauma on a chaise longue, or that the FBI rings you up whenever a serial killer is on the loose. Surveys show psychologists are generally trusted by the public — which makes it all the more ironic that so many still confuse the discipline with parlour tricks and TV clichés.

PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE DIFFERENT SPECIALISATIONS

Psychology is not a single subject but a collection of disciplines. Some focus on the brain and biology, others on thought processes, behaviour, or social influence. Just as mathematics isn’t only algebra and English isn’t just Shakespeare, psychology isn’t one thing either. It splinters into specialisms.

One of these specialisms is academic psychology, rooted in universities and research institutes.A developmental psychologist might spend months observing how children acquire language, regulate emotions, or negotiate fairness in play — mapping out the milestones of growth. A cognitive psychologist could design experiments on perception, reasoning, or decision-making, tracing how biases and mental shortcuts shape the way we interpret the world. Meanwhile, a social psychologist might study how group dynamics, prejudice, or social influence change behaviour in ways people rarely notice in themselves. Academic psychology asks the fundamental questions and produces the evidence base that the rest of the discipline builds on.

But psychology extends well beyond academia. Occupational psychologists study how to design workplaces that reduce stress and improve performance. Health psychologists work with patients to understand pain, illness, and the barriers to lifestyle change. Educational psychologists support schools, helping children with learning difficulties or developmental delays. Forensic psychologists operate in the justice system, assessing offenders, advising courts, and improving rehabilitation. Neuropsychologists map the links between brain injury or disease and changes in behaviour. Clinical and counselling psychologists apply psychological principles directly to therapy.

Each specialism has its own focus, but all are bound by the same aim: to use psychology to make sense of minds and to uncover human behaviour.

PSYCHOLOGISTS DISAGREE (A LOT)

Another irritating myth is that psychologists all believe the same things. If one psychologist argues serial killers are “made”, people assume the whole field agrees. The general public must imagine the entire profession meets weekly to vote on universal truths about the mind.

In reality, psychology is a gloriously untidy buffet of clashing theories — more like a debating chamber than a collective noun. Psychologists don’t share a single worldview: some treat behaviour as conditioning, others as cognition, and a few are still in the corner insisting Freud was right all along. And it’s not just the theories that differ — the methodology is split too. Some lean empiricism, and a few are busy shouting about lobsters.

That’s why asking a room full of psychologists the same question rarely produces a single answer. Pose the problem of why people conform, for example: a social psychologist might cite peer pressure experiments, a cognitive psychologist might point to decision-making biases, and an evolutionary psychologist might talk about survival advantages. Same question, three different answers — and none of them necesarily cancel the others out.

The “monolith” idea is comforting because it makes psychology sound like hard science, with one clear diagnosis and one right prescription. But psychology doesn’t work that way. It’s not a single script, it’s a debate — and half the fun is that the debate never ends.

A QUICK TOUR OF THE MAIN APPROACHES

In psychology, these different belief systems are called psychological approaches or perspectives. An approach isn’t just a vague outlook: it’s a framework for explaining how a person functions. A psychological perspoectyive will always involve a model of the mind, a method of research, a stance on nature versus nurture, and a treatment for mental illness.

Some approaches are practically allergic to each other. Humanists are anti-science and advocates of free will, while biological psychologists scoff at their ideas, and believ that the human condition is all down to genes, brain chemistry, and Darwin.

Still, there is occasional agreement in how some approaches layer onto one another: evolutionary psychology studies why the brain is designed as it is, cognitive psychology examines the programmes running on it, and neuroscience looks at the neural circuitry that makes those programmes possible.

A brief outline of the seven major psychological approaches are listed below:

THE PSYCHODYNAMIC APPROACH – Believes your past is haunting you, even if you don’t remember it. Childhood trauma is the ghostwriter of your personality.

THE BEHAVIOURIST APPROACH – Thinks we’re all Pavlov’s dogs: press the lever, get the treat, repeat.

THE HUMANIST/ POSITIVE APPROACH – Claims you can unlock your full potential through empathy, self-reflection, and maybe a crystal or two. Maslow’s pyramid scheme, basically.

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY – We imitate what we observe, especially if it looks cool or gets likes.

THE COGNITIVE APPROACH – Examines how dodgy thinking patterns, biased beliefs, and mental shortcuts shape behaviour — basically your brain’s glitchy software.

THE BIOLOGICAL APPROACH – Blames everything on genes, hormones, or evolutionary instincts — the John Money of the bunch, if you’re feeling cynical.

APPLYING THE APPROACHES: THE CASE OF STACEY MULLIGAN

To truly appreciate how wildly different psychological perspectives can be, let’s apply them to a real-life(ish) example: a case study we’ll call Stacey Mulligan. Each approach offers its own pet theory and preferred solution — and no two sound remotely alike. What emerges is less a consensus and more a six-way tug of war over Stacey’s soul.

MEET STACEY MULLIGAN

AGE: 31

NATIONALITY: American

OCCUPATION: Unemployed

ADDRESS: No fixed abode

NUMBER OF CHILDREN: 7, all of whom have been taken into care

WHO IS STACEY?

BACKGROUND

Stacey was born addicted to cocaine and spent her first weeks undergoing treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) — a condition caused by drugs like heroin or methadone passing through the placenta. By toddlerhood, she was in and out of care following neighbour complaints. The rest of her childhood was a rotating door of institutions and foster placements. By 11, Stacey had her first arrest — the start of a long record involving class-A drugs, shoplifting, public disorder, and solicitation.

She now struggles with meth and alcohol addiction and is believed to have borderline personality disorder. So… what went wrong? That depends on which psychologist you ask.

WHAT LED TO STACEY’S CURRENT SITUATION?

THE HUMANIST / POSITIVE APPROACH

Stacey hasn’t reached self-actualisation because no one ever gave her unconditional positive regard. Without genuine, empathetic relationships, she was never able to believe in herself — or even know who that self is.

THE PSYCHODYNAMIC APPROACH

Blame it on the mother. Stacey’s lack of a secure attachment led to unconscious feelings of abandonment, which now sabotage her adult relationships. Her behaviour is driven by unmet childhood needs buried deep in her psyche.

THE BEHAVIOURIST / LEARNING APPROACH

Stacey’s learned that drugs equal love. Her mum was warm and generous when high, and cold or abusive when sober — so Stacey learned to associate intoxication with care and connection, and sobriety with rejection.

THE SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY APPROACH

Monkey see, monkey do. Stacey watched her mum cope with life by using drugs, and simply followed suit. Her mother modelled addiction as both a coping mechanism and a lifestyle.

THE COGNITIVE APPROACH

Stacey believes she’s doomed — a “born addict” with no way out. Her self-schemas are soaked in hopelessness, and her BPD diagnosis has only confirmed her negative core beliefs.

THE BIOLOGICAL APPROACH

Stacey’s brain was damaged in the womb thanks to her mother’s crack use. This likely altered structures like the amygdala, reducing her ability to regulate emotions or resist impulsive behaviours.

As you can see, psychology isn’t a unified front — it’s a multi-perspective shouting match where each approach brings its own tools, assumptions, and blind spots. Stacey is not just a case study — she’s a test of the field itself. And depending on your lens, she’s either a traumatised child, a faulty brain, or a mislabelled schema waiting to be rewritten.

SUMMING UP:

SO, WHAT IS PSYCHOLOGY?

Psychology is the study of mind and behaviour. That’s the definition — and beyond that, everything’s up for debate. There’s no master theory, no sacred text, and no point pretending otherwise. But while people outside the field still think it’s all therapy, psychopath hunting and inspirational quotes, actual work is being done elsewhere.

For many academics, psychology has outlived its usefulness as a descriptor. One solution is for the different approaches to abandon this umbrella term and develop it as separate specialisations. After all, philosophy also addresses questions about the human condition, yet no one frames its ideologies as psychological.

However, as Kuhn observed, new disciplines often evolve, like science, which emerged from natural philosophy. However, Kuhn’s theory doesn’t entirely apply to psychology. Since psychology is rooted in the humanities, its journey to becoming a science is less straightforward.

For example, while no single approach has fully captured the complexity of human nature, five major approaches—

Behaviourism, Social Learning Theory, Cognitive, Biological, and Evolutionary psychology already explain most of what’s worth explaining — not perfectly, but scientifically. These aren’t competing approaches. They’re different angles on the same messy species. They just haven’t been stitched together properly.

The focus should be moving away from less scientific approaches, like humanism and psychoanalytic theories, and unifying these five perspectives into a cohesive, unified paradigm.

It could stop pretending to be a science — and just be one