THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

SPECIFICATION: Factors affecting attraction in romantic relationships: physical attractiveness and the matching hypothesis – The impact of physical appearance on attraction and the tendency for individuals to seek partners with a similar level of attractiveness.

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

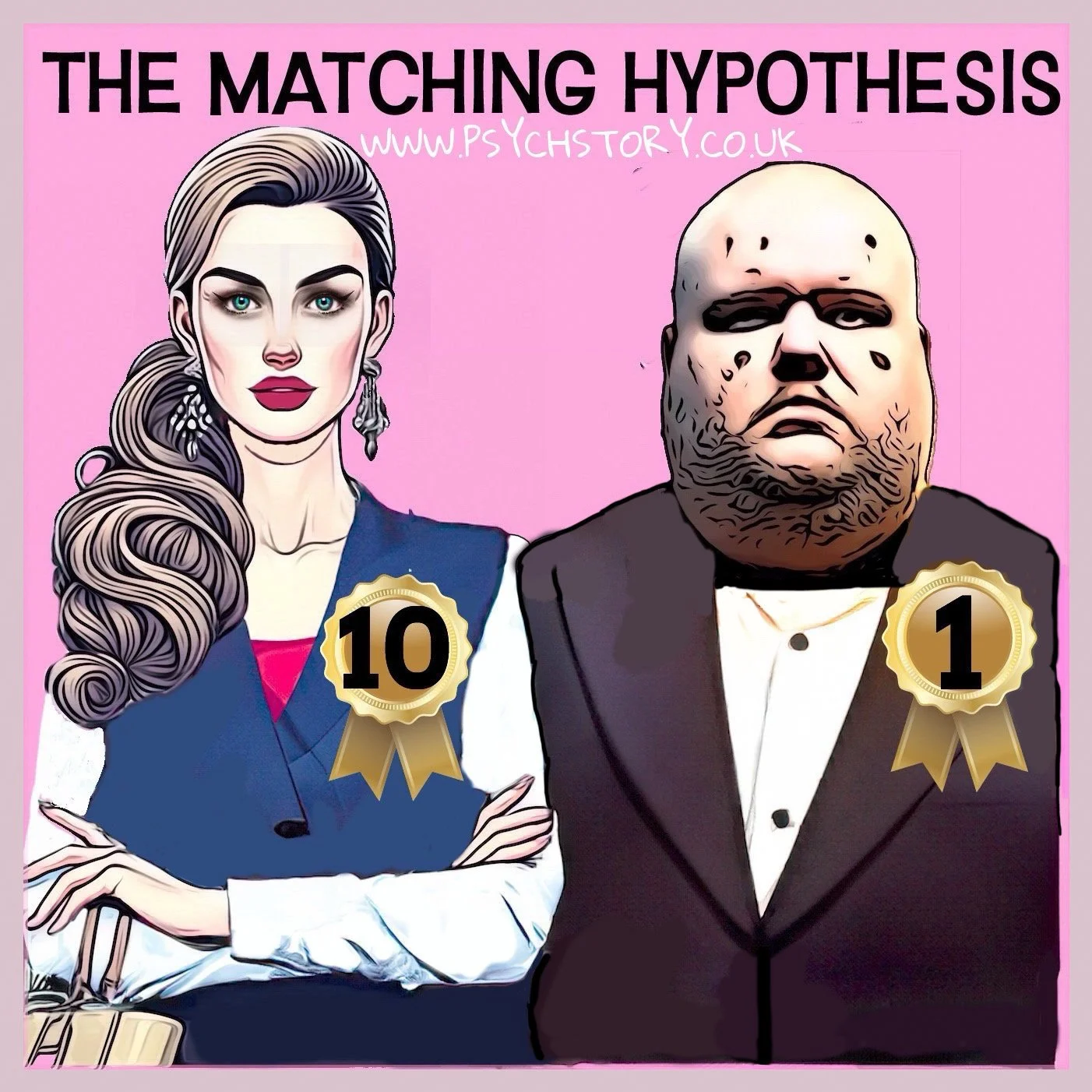

The matching hypothesis, also referred to as the matching phenomenon, suggests that individuals are more likely to enter and maintain committed relationships with partners who are of similar social desirability, particularly in terms of physical attractiveness.

Rather than always aiming for the most attractive person, individuals pursue partners within their attractiveness range, often to reduce the likelihood of rejection and ensure a more stable, reciprocal relationship.

HOW IT WORKS

The core idea is that people make realistic choices when selecting a romantic partner. While initial attraction may lead individuals to seek the most desirable partners, long-term relationships usually balance desirability and attainability. If someone continually aims for a partner who is much more beautiful than they are, they are more likely to experience rejection, leading them to adjust their preferences over time.

In simple terms, if everyone were rated on a scale from one to ten in terms of attractiveness, the theory suggests that:

A person who is a one is more likely to date another person who is a one.

A person who is a five is likelier to date another person who is a five.

A person who is a ten is likelier to date another person who is a ten.

People aim for the most attractive partner but also consider the likelihood of rejection. A person who is a five might be attracted to someone who is a ten, but if they consistently get rejected by people at that level, they will eventually focus on partners within their range. This idea originates from social psychology and was introduced by Elaine Hatfield and colleagues in 1966.

However, while physical appearance plays a central role in attraction, relationships where partners differ significantly in attractiveness may still be successful due to other compensatory factors. For example, individuals with higher social status, wealth, or influence may attract physically attractive partners despite an imbalance in looks. This is often observed in relationships where older, affluent men pair with younger, conventionally attractive women or where physical attractiveness is deprioritised in favour of financial security and social prestige.

RESEARCH STUDIES

WALSTER ET AL. (1966) – THE COMPUTER MATCH DANCE STUDY (Laboratory Experiment)

Walster et al. (1966) conducted a pioneering laboratory experiment known as the Computer Match Dance study to test the matching hypothesis, which proposes that individuals seek romantic partners similar in physical attractiveness. Researchers recruited 752 university students, whose attractiveness was independently rated by four judges to determine social desirability objectively. Participants believed they were matched based on questionnaire similarity, but pairings were actually randomised (except that no male was paired with a taller female). During a dance event, participants rated their assigned partners midway through the evening. Contrary to predictions, findings revealed that physical attractiveness was overwhelmingly the dominant factor influencing enjoyment rather than similarity in personality or intelligence. More attractive participants evaluated their partners harshly, challenging the matching hypothesis, even when attractiveness levels matched. A later follow-up study provided partial support, indicating that similarly attractive pairs continued interactions longer.

WALSTER AND WALSTER (1971) – FOLLOW-UP STUDY (Naturalistic Experiment)

To address ecological validity concerns, Walster and Walster (1971) conducted a naturalistic experiment, allowing participants more authentic interactions before choosing a partner. Unlike their original study, results supported the matching hypothesis: individuals expressed the greatest attraction towards partners who were similar in physical attractiveness. This suggested that, in realistic settings, matching based on attractiveness occurs more naturally.

MURSTEIN (1972) – PHOTOGRAPH RATING STUDY (Correlational Study)

Murstein (1972) conducted a correlational study assessing photographs of 197 real-life couples at various stages of their relationships (from casual dating to marriage). Unaware of actual pairings, eight independent judges rated each individual’s attractiveness. Findings supported the matching hypothesis: real-life partners typically had similar attractiveness levels. Murstein noted inflated attractiveness ratings due to positive biases in initial self and partner ratings; after controlling for these, the matching effect remained significant, reinforcing its validity.

HUSTON (1973) – FEAR OF REJECTION STUDY (Laboratory Experiment)

Huston (1973) conducted a laboratory experiment to challenge conventional views of the matching hypothesis. Participants viewed photographs of potential partners who had previously expressed interest, removing the risk of rejection. Results indicated participants consistently chose the most attractive available partner when rejection was not a concern, suggesting matching behaviour is driven more by fear of rejection than an inherent preference for similarity in attractiveness. However, this study’s ecological validity was limited since real-life dating rarely involves guaranteed acceptance.

BERSCHEID AND DION (1974) – EXPECTATIONS OF RELATIONSHIP OUTCOMES (Laboratory Experiment)

Berscheid and Dion (1974) conducted a laboratory experiment examining social perceptions about relationship success based on physical attractiveness. Participants rated photographs of couples who were either equally attractive or mismatched. Results supported the matching hypothesis, revealing that equally attractive couples were perceived as happier, more stable, and better potential parents. In contrast, mismatched couples were predicted to experience lower satisfaction and a higher likelihood of breakup, suggesting social expectations strongly favour matching.

BERSCHEID AND WALSTER ET AL. (1974) – REPLICATION OF MATCHING EFFECT (Laboratory Experiment)

Berscheid and Walster et al. (1974) replicated earlier findings through another laboratory experiment, exploring how attractiveness affects partner selection and relationship expectations. Participants chose ideal partners from photographs varying in attractiveness, overwhelmingly selecting the most physically attractive individuals. However, when considering long-term relationship success, participants believed similarly attractive couples would fare better, reflecting societal beliefs. This study also highlighted the "halo effect," with attractive individuals presumed to possess more positive personality traits, reinforcing attractiveness’s role in partner selection.

WHITE (1980) – REAL-LIFE DATING COUPLES (Correlational Study)

White (1980) conducted a correlational study involving 123 dating couples at UCLA, investigating whether similar attractiveness levels predicted relationship satisfaction. The findings supported the matching hypothesis, with similarly attractive couples reporting higher satisfaction and stronger feelings of love. White also found that romantic relationships operated like a marketplace, with individuals with more appealing alternatives sometimes valuing their current relationship less. Nevertheless, loyalty and commitment often prevailed, reinforcing matching as an important stabilising factor.

GARCIA AND KHERSONSKY (1996) – PERCEPTIONS OF COUPLES (Questionnaire-Based Study)

Garcia and Khersonsky (1996) used a questionnaire-based study to investigate how outsiders perceive couples as matched or unattractive. Participants viewed photos and completed surveys rating the couples' perceived relationship satisfaction, likelihood of breakup, and marital success. Results indicated that similarly attractive couples—particularly highly attractive pairs—were consistently perceived positively as happier and more stable. In mismatched pairs, the less attractive male partner was considered more satisfied, whereas the more attractive female was judged less satisfied. These findings supported the societal expectation favouring matching.

SHAW TAYLOR ET AL. (2011) – ONLINE DATING STUDY (Naturalistic/Correlational Study)

Shaw Taylor et al. (2011) conducted a naturalistic, correlational study within online dating contexts, rating the attractiveness of 60 males and 60 females and tracking their messaging behaviours. Participants initially aimed to contact partners who were more attractive than themselves, challenging the matching hypothesis. Nevertheless, reciprocation and successful interactions occurred primarily with partners of comparable attractiveness. These findings indicated that while individuals might aim aspirationally, matching emerges through realistic reciprocal interactions.

COYE CHESHIRE ET AL. (2011) – ONLINE DATING AND THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS (Naturalistic/Correlational Study)

Cheshire et al. (2011) conducted a comprehensive, naturalistic, correlational study examining the matching hypothesis using extensive real-world online dating data across four experiments. Results revealed that users frequently initiated contact with more attractive individuals, initially contradicting traditional matching expectations. However, reciprocal matches occurred primarily among individuals of similar attractiveness and desirability levels. Additionally, matches were based on multiple dimensions beyond attractiveness, including personality and intelligence, highlighting the complexity of romantic selection in digital contexts. The study concluded that although aspirational dating behaviours are shared online, realistic matching persists through mutual selection.

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH FINDINGS

Chronologically, initial studies (Walster et al., 1966) challenged the matching hypothesis, suggesting attractiveness alone dominated partner choice. Follow-up studies (Walster & Walster, 1971; Murstein, 1972; Berscheid & Dion, 1974; Berscheid & Walster, 1974; White, 1980) provided more substantial empirical support for matching, demonstrating couples typically select similarly attractive partners for stable relationships. Alternative interpretations (Huston, 1973) argue that matching stems from rejection fears rather than true preference. More recent investigations (Garcia & Khersonsky, 1996; Shaw Taylor et al., 2011; Cheshire et al., 2011) found evidence of aspirational initial behaviours but confirmed that long-term matching occurs through realistic social dynamics. Overall, these studies highlight attraction’s complexity, influenced by a dynamic interaction of physical attractiveness, social expectations, fear of rejection, and reciprocal processes in relationship formation.

EVALUATION OF THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

OVEREMPHASIS ON PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS

A common criticism of the Matching Hypothesis is that it disproportionately emphasises physical attractiveness in relationship formation, arguably oversimplifying a complex interplay of factors such as personality, intelligence, and shared values. However, empirical evidence strongly indicates that physical attractiveness remains a central driver of attraction, not only during initial encounters but also throughout relationships. For instance, Walster et al. (1966) and Berscheid & Walster (1974) consistently demonstrated the primary importance of attractiveness in initial romantic selection, driven largely by the robust psychological phenomenon known as the "halo effect," wherein attractive individuals are perceived to possess superior personality traits and social desirability.

Real-world evidence further reinforces society's persistent prioritisation of physical appearance. Industries directly tied to enhancing attractiveness—such as cosmetic surgery, beauty and skincare, fashion, dieting, and fitness—have experienced exponential global growth, reflecting profound societal investment in physical appeal. The global cosmetic surgery industry alone, projected to surpass $70 billion annually, demonstrates society’s tangible prioritisation of physical attractiveness as a core determinant of personal worth and romantic success. Similarly, the continuous growth of the fitness and fashion industries, alongside pervasive social media cultures that centre around physical beauty (e.g., Instagram influencers, TikTok aesthetics), provides empirical evidence of attractiveness's enduring societal importance.

Further supporting this viewpoint, evolutionary psychology (Buss, 1989; Gangestad & Scheyd, 2005) emphasises the adaptive significance of physical attractiveness, associating it with genetic fitness, reproductive potential, and health. Consequently, attractiveness remains deeply embedded in mating preferences, even among couples who remain together long-term. Indeed, relationship maintenance does not necessarily signal diminished importance of physical appeal; many relationships endure due to commitment, social pressures, economic dependence, or familial responsibilities rather than sustained attraction or sexual satisfaction.

Additionally, evidence from extradyadic behaviours and modern online contexts indicates that individuals frequently continue to prioritise physical attractiveness and sexual novelty despite relationship stability. High prevalence rates of infidelity, extensive consumption of pornography, and the explosive popularity of platforms such as OnlyFans, all underscore continued active pursuit of physically attractive or novel sexual partners outside established relationships (Mark, Janssen & Milhausen, 2011; Frederick & Fales, 2016). Such behaviours strongly suggest that the desire for physical attractiveness and sexual novelty persists independently of relationship duration or partner compatibility, potentially contradicting claims that attractiveness diminishes in importance as relationships mature.

In conclusion, while the Matching Hypothesis can be critiqued for its narrow focus on physical appearance—potentially minimising other critical relational factors—it nevertheless accurately captures the enduring and substantial societal and psychological emphasis placed upon physical attractiveness. Both empirical academic research and widespread real-world phenomena consistently affirm that physical attractiveness remains a central, powerful influence shaping relationship dynamics, attraction, and sexual behaviour over time

POWER IMBALANCES IN RELATIONSHIPS

However, the original Matching Hypothesis does not claim that partners have equal agency in choosing a mate, as social and economic power dynamics often influence real-world relationships. For example, a less attractive partner may compensate with other resources, such as financial stability or social connections. This suggests that, although criticism of this theory is common, it is not entirely valid.

Indeed, the Matching Hypothesis suggests that relationships are formed based on a cost-benefit analysis, where individuals weigh the rewards and drawbacks of a potential partner. In this context, women may be more likely to choose less physically attractive men if those men offer higher social status, financial security, or resources that contribute to long-term stability. This aligns with evolutionary theory, which argues that men and women have different reproductive strategies. Since women have a higher biological investment in offspring, they are more likely to prioritise resource acquisition over physical attractiveness when selecting a partner.

Thus, when compensation for looks occurs, women are more likely to trade physical attractiveness for wealth and status than men. This suggests two key points:

If a couple has the same social status, attractiveness tends to be more evenly matched, as no bargaining power is involved. In such cases, partners of equal economic and social standing may only be able to trade looks rather than other attributes.

The Matching Hypothesis is beta-biased, assuming that relationship formation works similarly for both sexes without fully considering gender-specific preferences. However, in reality, the Matching Hypothesis is alpha-biased, as evidence suggests that women are more likely than men to accept less attractive partners if they are from higher income or social classes.

This highlights an essential difference between the sexes that the theory does not fully account for. Again, evolutionary theory suggests that these patterns may be more relevant to men, as they have historically competed for high-status positions to attract mates. This reinforces the idea that attractiveness and status function differently for each gender in mate selection.

BROWN (1986) – LEARNED EXPECTATIONS AND THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

KEY ARGUMENT

Brown (1986) supported the matching hypothesis but provided an alternative explanation for why individuals form relationships with partners of similar attractiveness. Rather than choosing partners based on a fear of rejection, he argued that people develop a learned sense of what is "fitting" for them in relationships.

Individuals adjust their expectations based on what they can offer in a relationship. This self-assessment is shaped over time by social experiences, interactions, and feedback from others. Instead of aiming for the most attractive partner possible and fearing rejection, people naturally select partners they believe are realistic choices based on their perceived attractiveness and desirability.

Brown suggested that people internalise social feedback about their attractiveness, influencing their perception of their romantic value. Those who receive consistent validation of their attractiveness tend to have higher expectations for partners. Conversely, individuals who receive less positive social reinforcement may adjust their expectations downward and seek partners they believe they can realistically attract.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

Brown’s theory shifts the explanation away from a simple fear of rejection and towards self-perception and social learning. This explanation aligns with social exchange theory, as individuals subconsciously evaluate their value and seek equitable relationships where they feel desirable and secure. It also accounts for individual differences, as some people may overestimate or underestimate their attractiveness based on subjective self-perception rather than objective reality.

However, self-perception alone does not fully explain why some relationships are unequal, particularly those between wealthy men and beautiful women. According to Brown, these men are likely aware of the imbalance in attractiveness between themselves and their partners. Still, they may not fear rejection because their financial resources compensate for their lower physical appeal. This suggests that self-perception is only relevant when rejection is a concern—if an individual has other desirable attributes, they may feel secure despite an attractiveness disparity.

An imbalance in attractiveness may lead to feelings of inadequacy for men or women who lack alternative bargaining power. They might fear their partner will eventually leave them for someone of equal attractiveness, reinforcing that relationship stability depends on perceived equity.

Despite this, most people still desire the most attractive partner possible. However, self-perception, a lack of bargaining power, and fear of rejection prevent most individuals from actively pursuing the most beautiful people. Instead, people settle for more realistically attainable partners, making strategic choices based on what they can offer in return.

This is reflected in celebrity culture and parasocial relationships. The most admired public figures are rarely average-looking, as people consistently idolise the most conventionally attractive stars. The billions spent on plastic surgery and the beauty industry further illustrate that while people aspire to the most physically desirable partners, they ultimately negotiate based on what they can realistically achieve, whether through their looks, status, or other compensatory factors.

For this reason, the matching hypothesis shares key similarities with social exchange theory, as both suggest that relationships involve an assessment of personal value and strategic partner selection.

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL INFLUENCES

The Matching Hypothesis assumes that attraction operates universally, but cultural and societal norms significantly shape relationship choices. In some cultures, family influence, arranged marriages and economic considerations may take precedence over physical attractiveness, leading to partner selection based on factors beyond romantic attraction alone.

Additionally, one common criticism of the theory is that standards of attractiveness vary across cultures and historical periods, making the concept of matching seem subjective and fluid rather than a fixed rule. However, this criticism misinterprets the hypothesis. The Matching Hypothesis does not dictate what is considered attractive; rather, it states that individuals match with others based on the prevailing standards of attractiveness within their culture and social context.

Regardless of cultural differences in beauty ideals, many societies prioritise what they consider attractive as a bargaining tool in mate selection. Even in cultures where wealth, status, or family expectations dominate partner choice, physical attractiveness remains an important factor within the parameters of those cultural norms. This suggests that while the specific traits deemed attractive may vary, the tendency to use attractiveness as a social currency in mate selection is a consistent pattern across cultures.

This reinforces the idea that, rather than being invalidated by cultural differences, the Matching Hypothesis can be adapted to different social contexts, as it primarily describes a pattern of relationship formation rather than prescribing a fixed standard of beauty.

THE ROLE OF INDIVIDUAL PREFERENCES

Not everyone values attractiveness to the same extent. Some people prioritise emotional compatibility, intelligence, or shared interests overlooks. The hypothesis assumes people will naturally settle for someone at their attractiveness level, but individual preferences can lead to pairings that do not fit the expected pattern.

CHALLENGES FROM ONLINE DATING

The rise of online dating and social media presents significant challenges to the Matching Hypothesis, as it disrupts traditional mechanisms of partner selection. The hypothesis suggests that people choose partners based on realistic expectations of attainability, but modern dating platforms encourage idealised choices over practical ones.

IDEALISED ATTRACTION AND CURATED IDENTITIES

Dating apps and social media enable users to present highly curated versions of themselves, often through edited photos, carefully crafted profiles, and selective self-disclosure. This can distort perceived attractiveness, making individuals more likely to pursue partners outside their realistic attractiveness range. Rather than basing choices on real-world interactions, where rejection acts as a natural filter, online dating removes immediate feedback, allowing people to aim for more attractive partners than they might in face-to-face settings.

EXPANDED SOCIAL POOLS AND BROKEN BARRIERS

Traditional relationship formation was primarily restricted to immediate social circles, such as workplaces, universities, and community networks, where individuals were more likely to encounter people of similar social desirability. Online dating removes these geographic and social constraints, allowing people to connect with partners far beyond their usual environment. This increases opportunities for asymmetrical pairings, where partners may not align in attractiveness, status, or background.

DECOUPLING PHYSICAL APPEARANCE FROM RELATIONSHIP SUCCESS

While physical attractiveness still plays a role in initial attraction, online dating emphasises other factors, such as personality descriptions, shared interests, and communication skills. Long-distance relationships, which are far more common due to online interactions, often begin with text-based exchanges rather than visual attraction alone. This means that people may form emotional bonds before meeting in person, potentially leading to relationships where traditional matching based on looks is less relevant.

INCREASED REJECTION AND UNREALISTIC EXPECTATIONS

Despite the illusion of choice and limitless options, research suggests that online dating increases rejection rates as people compete for the most attractive users. This creates a paradox where individuals pursue partners well above their attractiveness level, only to experience frequent rejection, reinforcing self-perception biases. At the same time, the accessibility of lovely individuals online may discourage people from settling for realistic matches, leading to prolonged singleness or dissatisfaction with attainable partners.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS

While online dating does not invalidate the Matching Hypothesis entirely, it introduces new variables that complicate its traditional application. People may still seek partners within their attractiveness range, but expanded options, curated identities, and delayed face-to-face interaction allow more flexibility in mate selection. This suggests that while the Matching Hypothesis remains relevant, modern dating requires a more nuanced approach, incorporating social and technological influences into relationship formation.

LACK OF CONSISTENT EVIDENCE

While some studies support the Matching Hypothesis, research findings have been inconsistent, raising questions about its reliability. One major issue is that much of the data supporting the theory is correlational and non-experimental, making it difficult to establish cause and effect. Just because partners often appear to be matched in attractiveness does not mean that this is the reason they formed a relationship—other factors, such as shared social circles, mutual interests, or cultural norms, could influence partner selection. Without experimental manipulation, it is impossible to determine whether people actively seek partners of similar attractiveness or whether other forces naturally lead to such pairings.

Another common misconception about the Matching Hypothesis is that it only applies to physical attractiveness. However, the original theory does not state that looking alone determines romantic pairings. Instead, it suggests that people match based on overall social desirability, including personality, intelligence, wealth, status, or shared values. Studies that claim to contradict the hypothesis by showing that people pair based on other traits rather than looks may be misrepresenting the theory rather than disproving it. This misconstrual leads to confusion, as some researchers attempt to falsify the hypothesis based on an oversimplified, appearance-based interpretation rather than testing it in its intended, broader form.

Furthermore, findings on mate selection vary depending on context. Some studies suggest that attractiveness is more dominant in short-term dating scenarios. At the same time, factors such as personality, emotional compatibility, and financial stability become more influential in long-term relationships. This suggests that matching may operate differently across relationship types, further complicating efforts to test the hypothesis consistently.

Ultimately, the lack of experimental control, variability in findings, and frequent misinterpretation of the theory make it challenging to assess the actual validity of the Matching Hypothesis, leaving room for debate on its applicability in different relationship contexts.

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS AND SAME-SEX RELATIONSHIPS

The Matching Hypothesis is often applied to heterosexual relationships, but its relevance to same-sex relationships is less frequently explored. While the theory should, in principle, apply to all romantic partnerships, research suggests that gay and lesbian individuals may prioritise different factors in mate selection, which complicates how matching occurs in non-heterosexual relationships.

Gay men tend to place greater emphasis on physical attractiveness, similar to heterosexual men. Studies suggest that appearance-based matching is more prevalent in gay male dating culture, particularly in casual relationships. Physical traits such as youth, body shape, and facial symmetry often play a key role in attraction. This is reflected in online dating patterns, where gay men frequently assess potential partners based on looks before considering other factors. While long-term relationships involve more than just physical appeal, initial matching based on attractiveness appears stronger among gay men than lesbians.

In contrast, lesbians are generally less focused on physical attractiveness than both gay and straight men. Research suggests that emotional compatibility, personality, and shared life goals are more influential in lesbian relationships. This aligns with evidence that lesbian couples tend to engage in fewer short-term or casual relationships and prioritise long-term commitment more often. As a result, the matching process in lesbian dating may be based more on emotional bonding and shared interests rather than social desirability alone.

These differences challenge the Matching Hypothesis, as it assumes a universal focus on attractiveness, yet the importance of looks varies significantly depending on gender and sexual orientation. The theory appears to be more applicable to gay men, who tend to match on physical attractiveness, but less so for lesbians, who may prioritise other attributes. This also raises questions about how socialisation and gender roles influence mate selection, as men—regardless of sexual orientation—are generally more likely to emphasise physical traits. In contrast, women are often socialised to value emotional depth and long-term stability.

Additionally, the Matching Hypothesis assumes that attractiveness remains a stable factor in relationships, yet in both heterosexual and same-sex relationships, desirability can shift over time. A couple may start as an equal match in attractiveness or status, but changes such as ageing, weight gain, financial success, or career shifts can create disparities over time. Someone initially seen as desirable due to wealth may lose financial stability, or a once physically attractive partner may experience health-related changes. This suggests that while matching may explain initial attraction, it does not necessarily predict long-term compatibility.

Finally, the theory does not fully consider how relationships form in different social contexts. In same-sex dating, proximity, community size, and partner availability can shape mate selection in ways that differ from heterosexual dating. For example, in smaller LGBTQ+ communities, individuals may have fewer options to choose from, making matching based on attractiveness or social status less relevant than shared values and mutual understanding.

Ultimately, while the matching hypothesis can be applied to same-sex relationships, modifications are required to account for differences in mate selection priorities. In particular, the theory should be expanded beyond just attractiveness to reflect the role of emotional connection, long-term compatibility, and changing desirability over time.

THE MATCHING HYPOTHESIS AND RELATIONSHIP PRIORITIES

A key limitation of the Matching Hypothesis is that partner selection priorities change depending on whether an individual seeks a short-term or long-term relationship. While physical attractiveness is often central to initial attraction, it is not always the most critical factor in sustaining a long-term relationship.

Individuals tend to prioritise attractiveness for short-term dating, as these relationships are often based on immediate appeal rather than deeper compatibility. This aligns with the Matching Hypothesis, as people usually seek the most physically desirable partner they can attract. However, other traits such as kindness, emotional stability, and shared values become more important in long-term relationships. Research suggests that similarity in personality and life goals plays a more significant role in relationship satisfaction.

Some individuals also have different priorities for different types of relationships. They may seek an attractive partner for casual dating but prioritise emotional depth and reliability in a long-term partner. This suggests that matching is not solely based on attractiveness but on shifting priorities.

Furthermore, kindness, emotional intelligence, and compatibility influence relationship longevity. While the Matching Hypothesis explains initial attraction, it does not fully account for why some physically mismatched couples stay together while others who initially appeared well-matched eventually separate.

This suggests that while the Matching Hypothesis provides insight into early attraction, it overlooks the changing nature of mate selection and the role of personal attributes in long-term relationship success.