ECONOMIC THEORIES OF ROMANTIC RELATIONSHIPS

SPECIFICATION:

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

Social Exchange Theory analyses relationships as transactions in which individuals seek to maximise rewards and minimise costs. Satisfaction within a relationship depends on the perceived balance between what is given and what is received and how this compares to potential alternatives.EQUITY THEORY

Equity Theory emphasises the importance of fairness and balance in romantic relationships. It proposes that satisfaction is highest when both partners perceive an equitable distribution of inputs and outcomes. Inequity—whether one partner feels they are giving too much or receiving too little—can lead to dissatisfaction and breakdown.RUSBULT’S INVESTMENT MODEL

Rusbult’s Investment Model explains relationship persistence through three key factors: satisfaction, comparison with alternatives, and investment. Commitment to a relationship increases when individuals are satisfied, perceive few attractive options, and feel they have invested significantly (emotionally, financially, or otherwise), making the relationship more likely to endure.

PARALLELS WITH THE PRISONER’S DILEMMA

Two men are arrested, but the police do not possess enough information for a conviction. Following the separation of the two men, the police offer them a similar deal. If one testifies against his partner (defects/betrays), and the other remains silent (cooperates/assists), the betrayer goes free, and the cooperator receives the full one-year sentence. If both remain silent, both are sentenced to only one month in jail for a minor charge. If each 'rats out' the other, each receives a three-month sentence. Each prisoner must choose either to betray or remain silent; the decision of each is kept quiet. What should they do?’ If it is supposed here that each player is only concerned with lessening his time in jail, the game becomes a non-zero-sum game where the two players may either assist or betray the other. In the game, the sole worry of the prisoners seems to be increasing their reward. The interesting symmetry of this problem is that the logical decision leads both to betray the other, even though their individual ‘prize’ would be more fantastic if they cooperated.

The Prisoner's Dilemma, a classic model from game theory, provides a helpful metaphor for understanding the maintenance of romantic relationships through an economic lens. In a dilemma, two individuals must choose whether to cooperate (remain loyal) or defect (betray) without knowing the other’s choice. Although cooperation leads to the best joint outcome, rational self-interest often drives both parties to betray—leading to a worse result. This reflects the central tension in many relationships: whether to act for mutual benefit or protect oneself at the cost of the relationship.

This mirrors the assumptions behind Social Exchange Theory, which views relationships as cost-benefit analyses. Like prisoners trying to minimise their sentence, partners are often motivated to maximise personal rewards and minimise emotional or practical costs. If one partner feels they are investing more and receiving less (e.g., emotional support, time, affection), they may "defect" by withdrawing, cheating, or ending the relationship.

Equity Theory further expands this by highlighting the importance of fairness in distributing rewards and contributions. In a dilemma, if one person cooperates while the other defects, inequity arises, and resentment builds. Long-term satisfaction is more likely when both partners contribute fairly and perceive the relationship as balanced.

Finally, Rusbult’s Investment Model can explain why individuals may choose to "cooperate"—stay committed—even when high costs or dissatisfaction arise. Much like the Prisoner's Dilemma, the fear of losing investments (time, shared resources, emotional energy) or having poor alternatives can encourage people to remain in the relationship despite short-term frustrations, hoping for a long-term payoff.

Thus, the Prisoner’s Dilemma illustrates the complex decision-making processes that underpin relationship maintenance. Partners must trust, communicate, and sometimes sacrifice short-term gain to achieve long-term stability—just as cooperation in the game leads to the best overall outcome, even though self-interest may tempt individuals to act otherwise.

SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

HOMANS' SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY (1958–59)

George Homans (1958, 1959) proposed Social Exchange Theory (set) to understand human behaviour in social contexts using principles from economics, psychology, and sociology. Homans argued that human interactions are best understood as exchanges, where individuals seek to maximise rewards and minimise costs. This economic approach to social relationships became the foundation for later work by Thibaut and Kelley (1959), who applied these ideas to romantic and interpersonal relationships.

Social Exchange Theory proposes that all human relationships operate like social transactions, in which individuals engage with others by evaluating the costs and rewards of the interaction. People assess whether a relationship is worthwhile by weighing what they get out of it (rewards) against what they put in (costs), and comparing the result to what they believe they could get elsewhere.

A reward is any benefit that contributes positively to a person’s well-being or satisfaction. This may include love, affection, emotional support, sex, financial help, companionship, shared experiences, or even status and security.

In contrast, a cost is anything that requires effort or sacrifice. Examples include time, emotional strain, conflict, loss of independence, financial burden, unmet needs, or the demands of loyalty, commitment, or compromise.

SET assumes that people are consciously or unconsciously motivated to maximise rewards and minimise costs. When a relationship delivers more rewards than costs, the person is said to be in “profit”, which increases the likelihood of staying in the relationship. If the costs outweigh the rewards, the individual is considered to be in “loss”, making dissatisfaction, withdrawal, or breakdown more likely.

The overall value or worth of a relationship is calculated as:

WORTH = REWARDS – COSTS

This evaluation is not fixed; it can shift over time as circumstances change or as a person’s expectations evolve.

SOCIAL VS ECONOMIC EXCHANGES

According to Laura Stafford (2008), there are important differences between economic and social exchanges. Unlike economic exchanges, which are formal and transactional and often involve legal obligations or equal trade, social exchanges involve emotional connection, trust, and flexibility. They rarely involve explicit bargaining, and reciprocity is expected over time rather than in immediate, equal returns.

THIBAUT AND KELLEY’S STAGES OF RELATIONSHIP DEVELOPMENT (1959)

As part of Social Exchange Theory, Thibaut and Kelley (1959) proposed that relationships progress through a series of predictable stages, each reflecting how partners evaluate and manage rewards and costs over time:

SAMPLING STAGE

In this initial phase, individuals explore a relationship's potential costs and rewards, either through direct interaction (e.g., dating) or indirect observation (e.g., comparing others’ relationships). During this stage, partners begin to form early judgments about whether the relationship is likely beneficial, and they may also compare the potential relationship to other available options.BARGAINING STAGE

Once individuals begin engaging more seriously, they enter a phase of negotiation where each partner tests out different ways of giving and receiving rewards. They begin to establish patterns of interaction, identify what they need from each other, and evaluate whether the relationship is profitable. This stage involves learning how to balance contributions and expectations.COMMITMENT STAGE

As the relationship stabilises, partners become more committed. Exchange patterns become more predictable, and the relationship is maintained because both individuals feel their ongoing rewards outweigh their costs. Trust increases, and there is less conscious monitoring of every exchange.INSTITUTIONALISATION STAGE

In the final stage, the relationship becomes structured by established norms. Both partners have a shared understanding of how the relationship works regarding roles, rewards, and responsibilities. These expectations become internalised, and the relationship becomes embedded in daily life, often involving long-term commitments such as cohabitation, marriage, or family-building.

THE COMPARISON LEVEL

A key concept in Thibaut and Kelley’s (1959) Social Exchange Theory is the Comparison Level (CL), which refers to an individual's standard to judge the quality and satisfaction of their current relationship. This internal benchmark is shaped by two main influences: past relationship experiences—both romantic and platonic—and broader social and cultural expectations about what a relationship should offer. These expectations may come from sources such as family, friends, media, and personal observation, and together, they create a mental template of what one believes is deserved and realistically attainable in a relationship.

The CL, therefore, reflects two key ideas:

What an individual believe they are entitled to in a relationship (i.e. what they deserve) and

What they view as achievable or realistic in a relationship is based on prior experiences and societal norms.

Suppose the outcomes of a current relationship—such as emotional support, companionship, intimacy, or practical benefits—exceed this Comparison Level. In that case, the person will likely feel satisfied and perceive the relationship as worthwhile. In contrast, if the outcomes fall short of the CL, dissatisfaction may occur—even if the relationship is, by objective standards, relatively rewarding. For example, someone may be in a stable and supportive relationship but still feel unfulfilled if it doesn’t meet the level of passion or excitement they’ve come to expect. This highlights that relationship satisfaction is subjective and not simply based on the quantity of rewards and costs but on how those outcomes compare to internal expectations that have developed over time.

COMPARISON LEVEL FOR ALTERNATIVES

According to Social Exchange theorists, satisfaction alone does not determine whether a relationship will continue. To account for why individuals stay in or leave relationships, Thibaut and Kelley (1959) introduced the concept of the Comparison Level for Alternatives (CLalt). This refers to the lowest outcome a person is willing to accept, considering the potential rewards and costs of alternative relationships or life situations. In simple terms, the CLalt is an individual’s evaluation of whether they could do better elsewhere.

If the perceived outcomes of an alternative relationship—or even of being alone—are seen as more rewarding than the current situation, the individual is more likely to leave. However, this decision still involves a subjective cost-benefit analysis. For example, a new partner may appear more rewarding. Still, the person may weigh this against the practical costs of ending the relationship, such as financial loss, disrupting family life, or losing shared assets. Although the framework assumes rational decision-making, the evaluation is based on the individual’s perception of the relative outcomes, not emotional values or moral obligations.

Therefore, whether someone stays in or leaves a relationship is not simply about how satisfying the current relationship is. Rewarding relationships are more likely to be stable, as the high level of satisfaction reduces the perceived appeal of any alternative. However, even unsatisfying relationships can persist if no better options are available. Thibaut and Kelley (1959) referred to such situations as non-voluntary relationships, where individuals remain because the alternatives are seen as worse. For example, a person in an abusive or miserable marriage may stay due to financial dependence, fear of stigma, or lack of viable options. The relationship remains stable in these cases—not due to satisfaction, but because the CLalt is too low to justify leaving.

The CLalt is also closely connected to the concept of dependence, which refers to the extent to which a person feels they rely on their partner for relational outcomes, such as emotional support, financial security, or social status. Dependence is typically accepted in rewarding relationships, where the benefits outweigh the risks. However, in low-reward relationships, high dependence can lead to feelings of entrapment if no better alternatives exist.

IN SHORT…

REWARDS VS COSTS = ARE YOU IN THE RELATIONSHIP BLACK OR RED?

Social Exchange Theory sees relationships like emotional economics: if the rewards outweigh the costs, you’re in the black (profit); if the costs outweigh the rewards, you’re in the red (loss). This basic equation helps determine satisfaction and whether a person stays or leaves.

THE COMPARISON LEVEL (CL):

Your internal “standard” for what a good relationship looks like. It's shaped by your worldview—from personal experiences (platonic or romantic) to media portrayals and social influences. If your partner is unromantic or selfish, this may clash with what you believe you deserve—or it may feel familiar if you’ve been treated that way.

THE COMPARISON LEVEL FOR ALTERNATIVES (CLalt):

Is there plenty of fish in the sea? CLalt is all about what else is out there. You're more likely to leave if you believe you could get a better deal elsewhere. If alternatives are limited or worse, you’re more likely to stay—even in a bad relationship.

ASSUMPTIONS OF SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY: FACT-CHECKED

✔ Humans seek rewards and avoid punishments.

True. This is a core behavioural assumption underpinning SET.✔ Humans are rational beings.

True. SET assumes individuals weigh up options logically, aiming to maximise the benefit

SUPPORT FOR SOCIAL EXCHANGE

REWARDS VS COSTS

Kurdek and Schmitt (1986)

Investigated both heterosexual and same-sex couples over time.

They found that couples who perceived their rewards as outweighing their costs reported higher relationship satisfaction and commitment levels.

This supports SET’s fundamental principle that satisfaction arises when the net outcome (rewards minus costs) is positive.

Cate et al. (1982)

Participants in romantic relationships were asked to rate various relationship elements, including perceived rewards and costs.

Findings showed that perceived rewards were a stronger predictor of satisfaction than perceived costs.

This suggests that maximising rewards is central to maintaining a relationship rather than simply avoiding costs.

Hatfield (1979)

Hatfield found dissatisfaction increased when individuals perceived an imbalance between what they gave and received. Her findings support that people monitor their relationships regarding fairness and exchange, reinforcing that rewards and costs are central to relationship satisfaction.

Although more closely associated with Equity Theory, Hatfield's research indirectly supports SET by showing that perceived

COMPARISON LEVEL (CL)

Van Lange et al. (1997)

Demonstrated that individuals evaluate their relationships based on their expectations and past experiences—key Comparison Level components (CL) components.

Those whose relationships exceeded their expectations reported greater satisfaction, supporting that CL plays a significant role in determining how relationships are perceived.

Murstein et al. (1977)

Found that individuals develop an internal “ideal partner template” based on cultural norms, media portrayals, and personal history.

Satisfaction was higher when current partners matched or exceeded these ideals, supporting the concept of CL as a personalised standard for judging relationships.

COMPARISON LEVEL FOR ALTERNATIVES (CLalt)

Sprecher (2001)

The perceived availability and quality of alternatives strongly predicted relationship commitment and satisfaction.

Participants who saw better alternatives were less committed, even if their relationship was moderately satisfying.

This supports the claim that CLalt influences whether an individual stays in or leaves a relationship.

Simpson (1987)

An experimental study found that committed individuals were less likely to notice or evaluate alternative partners as attractive.

This suggests that people in satisfying relationships may mentally devalue alternatives to preserve their current bond.

The findings support SET’s idea that perceived alternatives play a key role in relational decision-making.

EVALUATION OF SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

REAL-WORLD APPLICATION

A key strength of Social Exchange Theory (SET) is its real-world application, particularly in therapeutic contexts. For example, SET forms the theoretical basis of Integrated Behavioural Couples Therapy (IBCT), in which couples are taught to increase the frequency of positive exchanges (such as affection, appreciation, and support) and reduce negative interactions (such as criticism or withdrawal). This practical use of SET demonstrates high mundane realism, translating the theory’s core principles into strategies to improve relationship quality.

The success of IBCT in clinical settings suggests that, despite its theoretical limitations, SET can offer valuable tools for understanding and enhancing real-life relationships. This strengthens the argument that SET is not only a descriptive model but can also be applied to foster healthier, more rewarding relational dynamics.

GENDER DIFFERENCES

Gender differences also appear to affect how people evaluate relationships. For example, research on stress and relationship conflict suggests that women may experience more significant anxiety about relationship problems, potentially making them more sensitive to relational dynamics. Additionally, evolutionary psychology proposes gender-based differences in emotional processing, with women typically showing higher levels of empathy and emotional investment.

These points raise concerns about beta bias in SET—the tendency to minimise or overlook fundamental differences between individuals or groups, particularly between men and women. The model’s assumption that all people engage in similar, rational calculations when evaluating relationships may not hold universally. Some individuals are more self-aware and analytical than others, while others rely more on emotion, intuition, or habit.

SINGLETONS

A further limitation of Social Exchange Theory is that it cannot adequately explain why individuals may remain single or leave a relationship, even when no better alternative exists. According to the theory, people are expected to stay in a relationship unless the perceived alternatives are more rewarding. However, individuals sometimes end relationships despite lacking a viable alternative or remain single for personal, emotional, or psychological reasons beyond cost-benefit analysis. This highlights a significant gap in the theory’s explanatory power. A robust psychological theory should be able to account for a wide range of behaviours and individual differences. The fact that SET fails to explain such common real-life scenarios undermines its overall credibility and universality.

The theory cannot explain why some individuals remain single or leave relationships even when there is no alternative. This is a problem because, IN REAL LIFE, this occurs. A good theory should be able to explain all individual differences and aspects so its credibility is lowered.

CULTURAL BIAS

Moghaddam (1998) argues that economic theories of relationships, such as Social Exchange Theory (SET), may reflect a strong cultural bias. These theories are rooted in Western, individualistic societies, where decisions about relationships are typically guided by personal satisfaction, autonomy, and rational self-interest. However, in collectivist cultures, relationship formation and maintenance are often influenced by family, social expectations, and community values rather than individual gain.

This poses a problem for SET's universality, as it may not accurately reflect the relational dynamics of the majority of the world's population, where collectivist values are dominant. Moghaddam suggests that such theories may be more appropriately studied emically—within the specific cultural context—rather than applied universally using etic (Western) assumptions.

However, it is also worth noting that even in collectivist settings, some form of exchange still occurs, though it may not be carried out by the individuals entering the relationship. For example, in arranged marriages, parents or elders often assess compatibility, family background, and balance of resources—essentially negotiating a mutually beneficial match on behalf of the individuals involved. While individuals may not engage in conscious bargaining, the social unit around them is. This suggests that exchange principles may apply, but the evaluation agents differ.

Therefore, although SET may not fully capture how relationships are experienced in collectivist cultures, it may still be relevant in explaining how matches are arranged and justified, albeit through communal rather than individual calculation. This underscores the need for culturally sensitive adaptations of the theory.

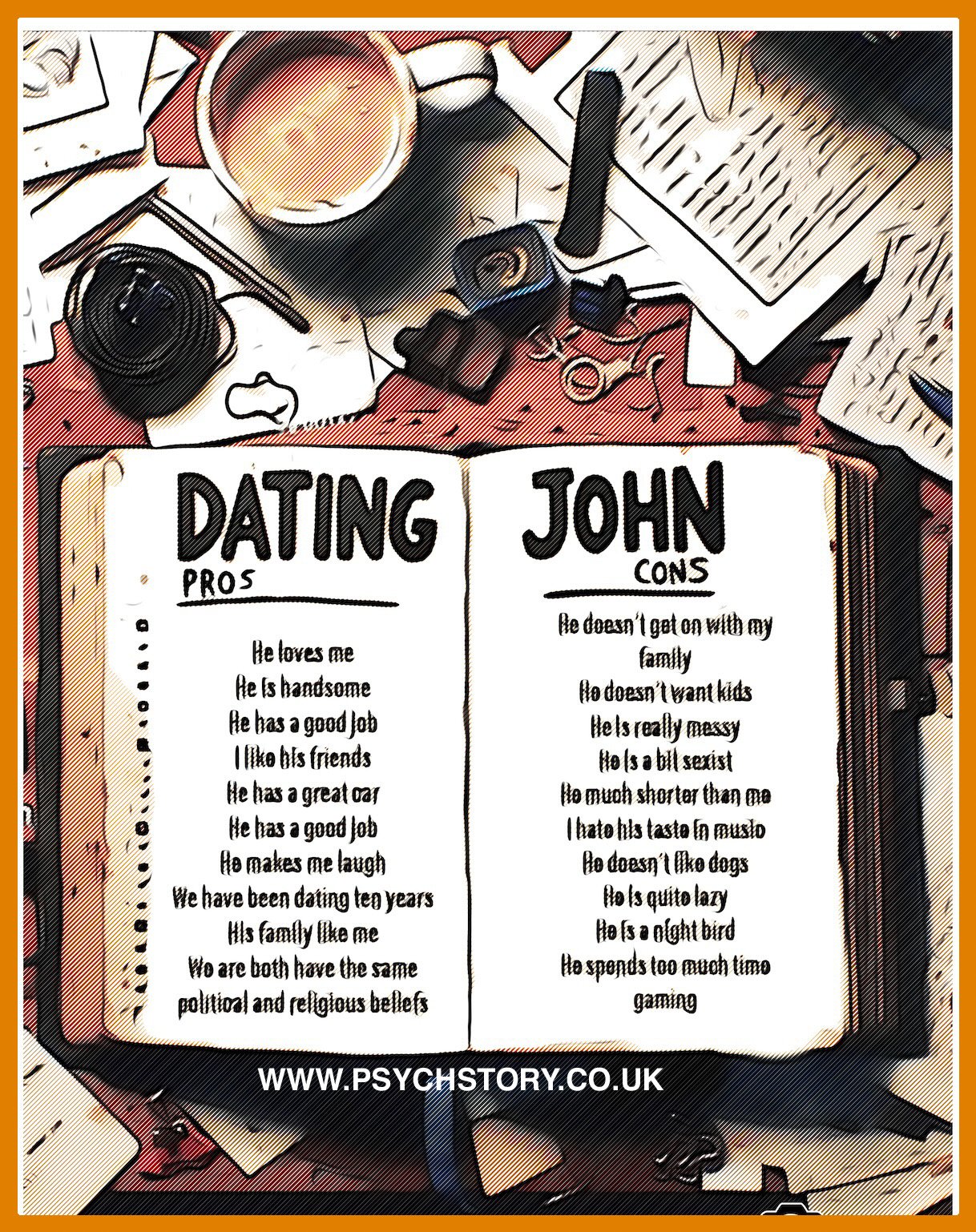

OPERATIONALISING REWARDS AND COSTS

A key methodological criticism of Social Exchange Theory is the difficulty in operationalising core concepts such as rewards and costs. These constructs are highly subjective, varying not only between individuals but also across different types of relationships. What one person perceives as a reward (e.g. emotional support) might be seen as a cost by another (e.g. emotional dependency), making it challenging to standardise definitions and compare findings across participants.

Because of this subjectivity, many studies that attempt to test SET rely on controlled laboratory settings using artificial procedures—such as hypothetical scenarios or contrived tasks—to measure these variables consistently. However, this reliance on artificial environments often results in low external validity, as the findings may not accurately reflect how relationships function in the real world, where emotional complexity, history, and context play a significant role.

IS PSYCHOLOGY A SCIENCE? – LIMITATIONS OF SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY

One major criticism of Social Exchange Theory (SET) concerns its scientific testability. For a theory to be considered scientific, it must be falsifiable—that is, it should be possible to design a test to prove it wrong. However, SET struggles to meet this criterion because its core concepts, such as "costs" and "rewards", are often vague, subjective, and difficult to operationalise. What constitutes a cost or reward varies widely between individuals and situations, making consistent measurement problematic.

As Sabatelli and Shehan (1993) point out, "It becomes impossible to distinguish between what people value and perceive as rewarding and how they behave." Almost any behaviour can be retrospectively interpreted as an attempt to seek rewards or avoid costs, which makes the theory unfalsifiable. For example, even someone staying in an abusive relationship could be said to be doing so because the perceived rewards—such as maintaining custody of children, avoiding homelessness, or fulfilling a distorted sense of self-worth—outweigh the costs.

By this logic, all behaviour can be explained post hoc as rewarding, even when it appears irrational or harmful. If a theory can explain every outcome, including extreme or contradictory cases, it loses predictive power and becomes difficult to disprove or test empirically. This challenges SET’s status as a scientific theory, as it risks being circular or tautological in its reasoning.

CAUSALITY

Michael Argyle (1987) raises a critical issue regarding the direction of causality in Social Exchange Theory (SET). He questions whether genuinely the Comparison Level (CL) causes dissatisfaction in a relationship or whether pre-existing dissatisfaction prompts individuals to evaluate their relationship regarding costs and rewards. In this view, people may not constantly calculate the value of their relationship unless problems arise. Therefore, SET may not explain the origins of dissatisfaction but instead serve as a post hoc justification. This undermines the theory's explanatory power, suggesting it may be more descriptive than predictive, and casts doubt on whether cost–reward analysis is a natural or primary feature of all relationships.

HUMANS ARE RATIONAL CALCULATORS?

Duck and Sants (1983) criticised Social Exchange Theory (SET) for being overly individualistic, arguing that it portrays relationships through a self-interested, economic framework. According to their critique, SET assumes individuals make relationship decisions in isolation, based purely on rational calculations of costs and rewards, while overlooking the interpersonal, emotional, and social processes that underpin real-life romantic partnerships. In practice, relationships are rarely maintained through calculated analysis alone—they are shaped by communication, emotional connection, shared meaning, and broader cultural expectations.

This concern is echoed by Steve Duck (1994), who argues that SET reduces intimate relationships to transactional exchanges, akin to buying a car or negotiating a contract. He suggests that applying a marketplace mentality to love and commitment fails to capture the emotional depth, irrationality, and moral values that often drive long-term romantic bonds. For many people, love is associated with sacrifice, trust, and emotional fulfilment, not constant cost-benefit analysis. Duck even claims that applying such a model to emotionally significant relationships—such as marriage or parenthood—can be misleading or even offensive, as it overlooks their relational and cultural meaning.

Similarly, Clark and Mills (1979) distinguished between exchange relationships, which follow the logic of reciprocity, and communal relationships, where acts of care are given out of genuine concern without expecting a direct return. They argue that many emotionally close relationships do not operate on a strict exchange model and that SET fails to capture the emotional complexity of genuine partnerships.

FALSIFICATION ISSUES

These criticisms challenge SET’s assumption that all relational behaviour is motivated by self-interest. However, this assumption may not be as narrow or unrealistic as critics suggest. SET does not claim that all individuals consciously calculate costs and benefits mechanically but that people act in rewarding ways, even if those rewards are emotional, symbolic, or aligned with personal values. For example, someone who takes a self-sacrificing role in a relationship—such as a caregiver or a “trad wife”—may still derive deep satisfaction, purpose, or identity from that role. This emotional fulfilment is a reward, even if the behaviour appears altruistic or imbalanced. In this sense, communal and exchange relationships can still fit within SET's framework if the individual is motivated by what they find rewarding.

However, this level of flexibility leads to a more fundamental problem: if any behaviour can be interpreted as a form of reward-seeking, then SET becomes unfalsifiable. Whether someone stays in a relationship out of love, leaves to be alone, or sacrifices endlessly for their partner, all these outcomes can be explained by redefining what "reward" means to the individual. This makes the theory tautological—it explains everything and, as a result, explains nothing in a scientifically useful way. No matter how contradictory, a theory that can justify any behaviour cannot make precise, testable predictions and, therefore, loses its scientific credibility. Rather than helping us understand why certain relationships succeed or fail, SET risks are applied only after the fact, reshaping their definitions to fit whatever outcome has already occurred. In this way, it becomes a closed loop: always applicable but never challengeable. That undermines its usefulness as a psychological theory and asks how far it can take us to understand real-world relationships.

EQUITY

A further criticism of Social Exchange Theory (SET) concerns its assumption that individuals are primarily motivated by maximising personal rewards and minimising costs. This raises an important ethical and relational question: Would someone truly feel satisfied in a relationship where they received all the rewards while their partner bore all the costs?

In theory, SET might predict high satisfaction for the individual benefitting most. However, such an imbalance often leads to guilt, discomfort, or moral conflict, damaging the relationship's emotional bond and long-term stability. It also assumes people are entirely self-serving, overlooking the role of empathy, mutual care, and fairness, which many people value deeply in close relationships.

Equity Theory is thought to address this issue more thoroughly, arguing that people strive for fairness and balance and that even being over-benefitted can result in dissatisfaction. Therefore, SET may oversimplify human motivation and ignore the emotional complexity involved in genuine relationships.

Equity Theory is often used as an updated version of SET, which makes the same fundamental mistake outlined above. If a person finds equity itself rewarding—if they feel pleased by fairness—then this still falls under the umbrella of reward-based motivation. The nature of the reward becomes irrelevant; what matters is how the subject perceives it. As a result, equity theory, like SET, remains vulnerable to the same criticism: it can retroactively explain any behaviour by redefining the individual's values, which again undermines its falsifiability.

ARE HUMANS REALLY THIS RUTHLESS?

Social Exchange Theory has been criticised for being overly reductionist. It attempts to explain complex human relationships through a relatively narrow, mechanistic framework based on pursuing rewards and avoiding costs. This economic model assumes that people engage in relationships primarily for personal gain, which risks overlooking human connection's emotional, altruistic, and moral dimensions.

For example, Hays (1984) found that individuals valued giving support as much as receiving it in friendships, highlighting that relationships are not consistently maintained through self-interest alone. This challenges SET’s assumptions and supports more balanced models, such as Equity Theory, which emphasises fairness, mutual benefit, and emotional reciprocity as crucial for relationship stability.

Critics argue that reducing relationships to a transactional process ignores the complex emotional, cultural, and interpersonal factors influencing how we form and sustain bonds. A more eclectic or integrative perspective incorporating emotional, cognitive, and social dimensions may offer a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of human relationships.

Still, the question remains: is SET’s portrayal of humans as rational calculators so implausible? From the evolutionary psychology perspective, this view may be more accurate than critics suggest. Humans have evolved to make strategic decisions in mate selection—seeking partners who offer the best reproductive, emotional, or social return on investment. The concept of the “selfish gene” (Dawkins, 1976) proposes that even altruistic behaviours are ultimately geared towards maximising genetic success. In this context, the idea that people unconsciously weigh rewards and costs is not cynical but adaptive.

Seen this way, SET’s assumption that people seek to maximise personal benefit—even in romantic relationships—may not be emotionally cold but evolutionarily rational. Rather than treating humans as unfeeling accountants, the theory might reflect the strategic intelligence that underpins our social behaviour, even when it occurs below conscious awareness.

WALSTER’S EQUITY THEORY (1978)

AN ALTERNATIVE ECONOMIC EXPLANATION

Equity Theory provides a more socially sensitive alternative to Social Exchange Theory (SET) in explaining how romantic relationships are maintained. Whereas SET is based on the idea that individuals are motivated to maximise rewards and minimise costs, Equity Theory focuses on fairness and perceived balance between partners. It is not the absolute value of rewards or costs that determines satisfaction but rather the relative distribution of these inputs and outcomes across both individuals.

According to Equity Theory, people expect relationships to feel fair. Each partner’s inputs (e.g. time, effort, emotional labour, childcare, financial contribution) should be proportional to the outcomes they receive (e.g. affection, support, security, companionship). Importantly, this does not mean that both partners contribute or benefit equally. A relationship can still be perceived as equitable even when one partner gives significantly more—as long as both feel the distribution is fair.

Example: One partner may work full-time and contribute financially, while the other manages the home and provides emotional support. The relationship remains balanced and satisfying as long as both partners perceive the arrangement as fair.

RESPONSES TO INEQUITY

When a relationship becomes inequitable, the under-benefitted and over-benefitted partners are predicted to experience psychological discomfort.

The under-benefitted partner may feel resentment, frustration, or anger, believing they contribute more than they receive.

Interestingly, the over-benefitted partner is also expected to feel uncomfortable—typically guilt or shame—due to the imbalance.

This makes Equity Theory distinct from other economic models, as it recognises that even those in a “better” position can be negatively affected by unfairness.

THE ROLE OF INVESTMENT AND RELATIONSHIP STAGE

How partners respond to inequity may depend on the stage and seriousness of the relationship.

In short-term relationships, where emotional investment is low, a perceived imbalance may lead to immediate dissatisfaction and even relationship breakdown since there is little to lose.

In long-term relationships, however, partners may tolerate temporary unfairness due to the high investment already made—whether emotional, financial, or practical. These couples are more likely to attempt to restore equity before considering ending the relationship.

MONITORING EQUITY SUBCONSCIOUSLY

Equity is often monitored subconsciously rather than through deliberate calculation. Partners may not explicitly track each other’s behaviour, but they generally know whether their relationship feels balanced. The relationship will likely remain satisfying if both perceive that they receive roughly what they deserve.

OTHER FACTORS: SUBJECTIVE PERCEPTION

A key feature of Equity Theory is its emphasis on subjective perception. What one person considers a fair exchange may not be seen the same way by another. For instance, some individuals might feel rewarded by generosity or sacrifice, especially if these acts align with their values or identity.

Example: A partner who identifies as a “traditional wife” may take pride in contributing more to household duties, not seeing this as unfair but as personally fulfilling.

This highlights a significant limitation: what counts as fair or unfair is not universal but is interpreted through each individual’s values, personality, and social conditioning.

FOUR PRINCIPLES OF EQUITY THEORY

Walster, Traupmann, and Walster (1978) identified four key principles underlying Equity Theory:

INDIVIDUALS SEEK TO MAXIMISE OUTCOMES

People are motivated to gain as much as possible from a relationship while keeping costs low. In this context, outcomes are calculated as rewards minus expenses.

Example: A person might value emotional support, affection, and sex as “rewards,” while “costs” might include arguments, compromise, or financial pressure. If the rewards outweigh the costs, the individual will likely feel satisfied.FAIRNESS IS NEGOTIATED THROUGH TRADE-OFFS

Equity doesn’t always mean equal contribution in every area—it’s about balance. Partners may offer different things to the relationship, but both should feel they are getting a fair return for their efforts.

Example: One partner may take on more childcare and housework while the other works longer to support the household financially. As long as both perceive this exchange as fair, equity is maintained—even if the actual contributions differ.INEQUITY CAUSES PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS

When a relationship feels unfair, it creates emotional discomfort.

Under-benefitted partners may feel resentment, frustration, or even betrayal if they believe they give more than they receive.

Over-benefitted partners might experience guilt or feel pressured to “make it up” to their partner.

Example: If one partner always compromises, pays for everything, or makes all the effort while the other does very little, this imbalance will eventually lead to dissatisfaction.

INDIVIDUALS ATTEMPT TO RESTORE EQUITY

When people notice an imbalance, they are usually motivated to correct it by changing their behaviour, asking for more in return, or reframing what they consider fair.

Example: A partner who feels they’re doing all the housework may ask their partner to do more, reduce their effort to match, or mentally justify the imbalance (e.g., “They’re working long hours—this is my way of contributing”).

RESEARCH SUPPORT FOR EQUITY THEORY:

HATFIELD, UTNE AND TRAUPMANN (1979)

Investigated the emotional impact of perceived inequity in romantic relationships. They studied individuals who felt either under-benefited or over-benefited and found that those who perceived themselves as under-benefited reported feelings of anger, deprivation, and resentment. Meanwhile, individuals who felt over-benefited experienced guilt and discomfort. These findings strongly support Equity Theory, as they demonstrate that both forms of inequality—receiving too little or too much—are associated with emotional dissatisfaction. Crucially, the researchers found that ongoing inequity was often linked to relationship breakdown, suggesting that perceived fairness is essential for relationship maintenance.

VAN YPEREN AND BUUNK (1990)

Conducted a longitudinal study with 259 couples—84% married and 16% cohabiting—recruited through a local newspaper. Participants completed questionnaires using the Hatfield global satisfaction measurement to measure perceived relationship equity. Initial results showed that 65% of men felt their relationship was equitable, 25% felt over-benefited, and 25% of women reported feeling under-benefited.

After a one-year follow-up, the researchers found that those who initially reported equitable relationships were the most satisfied. This was followed by participants who felt over-benefited, while those who felt under-benefited were the least satisfied. These findings support the central claim of Equity Theory: that perceived fairness is closely linked to long-term satisfaction. The study also shows that inequity—particularly when one partner feels they are giving more than they receive—can erode satisfaction over time and threaten the relationship's stability.

STAFFORD AND CANARY (2006)

In a study of over 200 married couples, Stafford and Canary found that those who perceived their relationship as equitable reported more relational maintenance behaviours (e.g. showing affection, engaging in shared tasks, constructive communication).

Implication: Equity influences satisfaction and predicts how actively partners work to maintain the relationship.

This supports Equity Theory’s claim that fairness contributes to relationship stability and ongoing commitment.

DEMARIS (2007)

Using data from a national survey of over 1,000 married individuals in the US, DeMaris found that perceived inequity significantly predicted lower marital quality, mainly when wives felt under-benefitted.

Interesting finding: Women seemed more sensitive to inequity than men, suggesting gender differences in how equity impacts relationship satisfaction.

This adds nuance to Equity Theory, raising questions about whether its principles apply equally across sexes.

BUUNK AND VAN YPEREN (1991)

In a follow-up study, Buunk and Van Yperen found that under-benefitted individuals experienced the most dissatisfaction, mainly when the imbalance persisted over time.

Importantly, dissatisfaction wasn't just short-term. Long-term inequity predicted more significant emotional distress and a higher likelihood of relationship breakdown.

KAPLAN AND ARONSON (1980)

In an experimental study, participants were asked to evaluate a fictional relationship. When they read about a couple whose partner contributed significantly more than the other, they rated the relationship as less likely to last and less satisfying than when the couple was described as balanced.

Conclusion: Observers also associate equity with satisfaction, supporting the idea that equity is subjectively felt and socially recognised.

EVALUATION OF EQUITY THEORY

SUPPORTING RESEARCH

There is strong empirical support for Equity Theory. Hatfield et al. (1979) found that individuals who perceived themselves as under-benefitted reported anger and resentment, while those who were over-benefitted experienced guilt and discomfort. Similarly, Van Yperen and Buunk (1990) found that couples who perceived their relationship as equitable were the most satisfied one year later. Those who felt under-benefitted were the least satisfied, suggesting that perceived fairness is closely tied to long-term relational stability.

REAL-WORLD APPLICATIONS 🧠 COGNITIVE REFRAMING TO REDUCE DISTRESS

When people experience inequity but cannot resolve it directly (e.g. due to life circumstances or long-term obligations), they may reframe their perceptions of fairness to reduce psychological discomfort. For instance, a partner may downplay their efforts or rationalise their partner’s lack of contribution. This aligns with Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance and adds psychological depth to Equity Theory.

This shows that equity can be restored behaviourally (by adjusting inputs/outputs) and mentally, which helps explain relationship persistence under challenging contexts.

THERAPEUTIC VALUE – DIAGNOSTIC USE IN COUPLES THERAPY

Equity Theory provides a valuable framework in relationship counselling, helping partners recognise and communicate perceived imbalances. Unlike SET, which often focuses on tangible costs and benefits, Equity Theory addresses emotional labour and fairness, making it especially useful in addressing issues like resentment, burnout, or underappreciation.

This adds practical validity and makes Equity Theory relevant in real-life relationship interventions.

EVOLUTIONARY PERSPECTIVE ON FAIRNESS

Though not originally evolutionary, the desire for fairness may have evolved as a mechanism to maintain cooperation and commitment. Perceived equity likely stabilised in pair-bonding, ensuring long-term investment and reducing defection risks. Thus, perceptions of fairness may be biologically adaptive, not just socially constructed.

This theoretical extension adds depth and aligns the theory with broader biological models of cooperation and trust.

EQUITY AND POWER IMBALANCE

Equity Theory is instrumental in addressing power dynamics within relationships. An ongoing imbalance in contributions and rewards can reflect or reinforce control, dependence, or emotional manipulation. Unlike SET, Equity Theory highlights how imbalance can impact self-worth and emotional well-being, even when “rewards” are technically present.

This makes it more sensitive to gendered or abusive dynamics, giving it an edge in capturing realistic relationship complexity.

TAUTOLOGICAL AND UNFALSIFIABLE — COMMON TO ALL ECONOMIC THEORIES

A widespread criticism of Equity Theory—and economic models more broadly—is that they risk becoming unfalsifiable. Suppose someone appears to tolerate an imbalanced relationship but claims to be happy. In that case, the theory can reinterpret that feeling of satisfaction as evidence that the situation is equitable to them. In this way, the definition of equity becomes circular: if perceived fairness equals satisfaction, then any emotionally fulfilling relationship can be justified as equitable, regardless of the actual distribution of costs and benefits.

This mirrors the same issue in Social Exchange Theory: rewards are so broadly defined that any behaviour can be reinterpreted post hoc as “profitable.” As a result, both theories may explain everything—but predict nothing. Their flexibility undermines their scientific validity because no conceivable relational behaviour can disprove the hypothesis. In trying to account for every possible outcome, the theory loses rigour.

GENDER DIFFERENCES

Research suggests that men and women may perceive and react to inequity differently. DeMaris (2007) found that women were more likely than men to report distress when under-benefitted, possibly due to socialisation or differing relational expectations. Equity Theory treats all individuals as reacting similarly to imbalance, which may limit its generalisability.

OVERLY RATIONAL AND REDUCTIONIST

Critics argue that Equity Theory, like other economic theories of love, oversimplifies relationships by assuming people constantly monitor fairness and make calculated judgements. In reality, emotions, values, and unconscious processes play a major role. Many couples don’t "keep score" in this way, particularly in communal relationships, where acts of care are given freely rather than in exchange for something.

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN EQUITY PERCEPTION

Equity Theory assumes that all individuals are equally motivated by fairness, but research shows that this isn't always the case. Huseman et al. (1987) found that people vary in how much equity matters to them. They identified three personality types:

THE BENEVOLENT: those who are comfortable giving more than they receive

THE ENTITLED: who expect to receive more regardless of their input

THE EQUITY SENSITIVES: who prefer a balanced give-and-take

This undermines the universality of Equity Theory, as it shows that not everyone experiences inequity as distressing, challenging its predictive power.

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES IN RESEARCH

While studies such as Van Yperen and Buunk (1990) support Equity Theory, their methodology raises concerns. Participants were recruited through local newspapers, leading to sampling bias and limited generalisability. Questionnaires also open the findings to social desirability bias, as participants may downplay dissatisfaction to appear more content.

As with SET, actual experiments are impossible, making it difficult to establish causality. The theory relies heavily on correlational or self-report data, reducing scientific rigour.

DOESN’T ACCOUNT FOR RELATIONSHIP TYPE

Clark and Mills (1979, 2011) argued that Equity Theory wrongly assumes all relationships operate like economic exchanges. They distinguished between:

Exchange relationships, where balance and reciprocity are tracked (e.g. workplace interactions)

Communal relationships, such as close friendships or romantic partnerships, where support is given out of care, not in expectation of return

Later findings suggested that equity is more influential in non-romantic or casual relationships and less consistently supported in romantic ones, limiting the theory's scope and applicability.

LINEARITY, OPENNESS, AND DEVELOPMENTAL LIMITATIONS

Katherine Miller highlighted conceptual issues with Equity Theory and similar economic models. She criticised them for assuming that:

All relationships aim toward closeness, which may not always be the case

Openness is always desirable when, in reality, some relationships rely on boundaries

Development is linear when relationships often evolve in non-linear ways, with periods of regression, crisis, or stasis.

This suggests that Equity Theory may oversimplify real-life romantic relationships' complex, fluid nature.

CONCLUSION

Equity Theory is a valuable framework for understanding the role of fairness and mutual investment in romantic satisfaction. It is supported by research and has intuitive appeal. However, it is limited by individual differences, gender assumptions, and an overly rational model of human behaviour. Most importantly, like Social Exchange Theory, it risks becoming tautological—redefining any behaviour as equitable so long as the individual feels satisfied. This severely limits its scientific value and predictive power. While still valuable, it may work best when used alongside other theories, such as Rusbult’s Investment Model, which better accounts for long-term emotional commitment.

RUSBULT’S INVESTMENT MODEL (2011)

Rusbult’s Investment Model was developed to explain commitment in romantic relationships more accurately than traditional economic theories such as Social Exchange Theory (SET). While SET focuses on the balance between rewards and costs, Rusbult argued that commitment is not based on satisfaction alone but depends on how much a person has invested in the relationship and what alternatives are available. The model identifies three core components influencing a person's likelihood to stay in a relationship: satisfaction level, investment size, and comparison with alternatives.

SATISFACTION LEVEL

Satisfaction refers to the extent to which a relationship meets the needs and expectations of both partners. It is based on the perceived ratio of rewards to costs, where rewards might include emotional support, companionship, intimacy, financial stability, or sexual fulfilment. In contrast, costs may involve time, stress, conflict, or compromise.

A partner is likely to be satisfied if they feel their relationship delivers more rewards than it costs and if their emotional, practical, or physical needs are being fulfilled. High satisfaction contributes directly to higher levels of commitment.

INVESTMENT SIZE

Investment is what an individual puts into a relationship that would be lost if the relationship were to end. Rusbult distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic investments:

Intrinsic investments are those put directly into the relationship, such as time, emotional energy, shared experiences, effort, and self-disclosure.

Extrinsic investments are things created or acquired due to the relationship, such as mutual friends, shared possessions, financial assets, or even children.

The more a person has invested, the more they stand to lose if the relationship ends. As a result, high investment can increase commitment, even when satisfaction is relatively low. This explains why some people remain in unhappy or even abusive relationships—because they feel they have invested too much to walk away.

COMPARISON WITH ALTERNATIVES

This factor refers to an individual’s assessment of whether they could have a more rewarding relationship elsewhere—either with another partner or by being alone. If alternatives are perceived as less satisfying, commitment will likely remain high, even if the current relationship is not ideal. On the other hand, commitment may decrease if a person believes they could be happier with someone else (or single).

In the early stages of a relationship, commitment is often high due to intense satisfaction, low investment risk, and limited awareness of better alternatives. However, commitment may decline if satisfaction drops or better options become available.

OVERALL COMMITMENT

According to the model, commitment is the central variable determining whether a relationship is maintained or dissolved. Even when low satisfaction, individuals may remain committed due to the size of their investments and the lack of appealing alternatives. This commitment is a more reliable predictor of relationship longevity than satisfaction alone.

Unlike SET, which primarily focuses on current rewards and costs, Rusbult’s model accounts for the history of the relationship (investments) and the future possibilities (alternatives), making it a more complete and realistic explanation of how romantic partnerships endure or break down over time.

EVALUATION OF RUSBULT’S INVESTMENT MODEL

SUPPORTING RESEARCH

Rusbult (1983) conducted a longitudinal study with heterosexual college students over 7 months, asking participants to complete questionnaires about their relationships every few weeks. The findings revealed that during the early “honeymoon” phase, individuals were not particularly concerned with the balance of rewards and costs. However, as the relationships developed, three key factors predicted long-term commitment: satisfaction, investment, and perceived alternatives. This supports the model by showing that rewards and costs may be less relevant in the early stages but become increasingly important over time, aligning with the theory’s emphasis on rational cost-benefit analysis and comparison levels as predictors of relationship persistence.

Rusbult and Martz (1995) further demonstrated the model’s real-world relevance by applying it to abusive relationships. Their findings suggested that individuals with high investments (such as shared children, finances, or emotional energy) and few perceived alternatives may choose to remain in relationships, even when they are physically or emotionally harmful. This supports the model’s claim that commitment does not always depend on current satisfaction—it may also be maintained due to a desire to avoid losing substantial investments. This helps explain why some people remain in unhealthy or non-rewarding relationships, making the theory applicable to a broader range of relational dynamics, not just healthy or romantic ones.

EVALUATION OF RUSBULT’S INVESTMENT MODEL

SUPPORTING RESEARCH

There is strong empirical support for Rusbult’s Investment Model. However, it is essential to note that much of this support comes from non-experimental, correlational research rather than controlled laboratory studies. For example, Rusbult (1983) conducted a longitudinal study tracking heterosexual college students over seven months. Participants completed regular questionnaires about their romantic relationships. The findings revealed that in the early “honeymoon” phase, individuals were less concerned with costs and rewards. However, as relationships matured, three core factors consistently predicted commitment: satisfaction, investment, and perceived alternatives. This supports the model’s emphasis on cost-benefit analysis, investment over time, and ongoing comparison with potential alternatives as key determinants of long-term relationship maintenance.

Further real-world support comes from Rusbult and Martz (1995), who studied women in abusive relationships. They found that even when satisfaction was low, many women remained committed due to high investments (e.g. shared children, financial dependence, emotional history) and few perceived alternatives. While this supports the model’s claim that commitment can exist without satisfaction, it raises ethical and conceptual concerns. Critics argue that this interpretation risks oversimplifying the lived reality of abuse by implying that victims stay because they are invested or lack alternatives—without fully addressing factors like coercive control, fear, trauma bonding, or a lack of structural support (e.g. housing, legal aid, social stigma). As such, this application may risk pathologising victims’ decisions through an economic lens that doesn’t fully capture the psychological and social complexity of abusive dynamics.

A meta-analysis by Le and Agnew (2003) provided further support. They reviewed data from over 50 studies across different relationship types (including same-sex relationships and various cultures) and found that satisfaction, investment, and alternatives consistently predicted commitment. This reinforces the model’s cross-cultural and cross-demographic applicability, although these studies rely primarily on self-report and correlational designs.

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

Despite its empirical support, the investment model is subject to several methodological limitations:

Self-report measures: Many studies, including Rusbult’s original research, relied on self-report questionnaires. While useful for capturing subjective perceptions (e.g. investment, satisfaction), such measures are highly vulnerable to social desirability bias, retrospective distortion, and demand characteristics, especially when discussing sensitive topics such as relationship abuse or dissatisfaction. This reduces internal validity.

Sample bias: Rusbult’s original study used heterosexual college students with limited life experience and typically short-term relational outlooks. This limits population validity, as the findings may not generalise to older, married, non-heterosexual, or culturally diverse populations.

Correlational design: Much of the research supporting the model is correlational, meaning causality cannot be established. For instance, we cannot determine whether investment causes commitment or whether people who have already committed to it perceive greater investment. This undermines the model’s predictive value.

Extraneous variables: Romantic commitment is shaped by many other factors not considered by the model, such as personality traits, attachment styles, socio-economic status, or mental health. These are rarely controlled for, making it challenging to isolate satisfaction, investment, and alternatives as primary causal variables.

Ethical considerations: Research on abuse survivors (e.g. Rusbult & Martz, 1995) raises serious ethical concerns. While such work is valuable for understanding commitment under extreme conditions, it must be handled with great care to avoid re-traumatising participants, reinforcing stigma, or misrepresenting coercive dynamics as mere “investment choices.”

REAL-WORLD APPLICATION

One of the model’s main strengths is its ability to explain real-world relationship maintenance, particularly in non-ideal circumstances. For instance, Rusbult and Martz (1995) found that many women in abusive relationships remained committed due to high investment and low perceived alternatives—not because of satisfaction. While this offers valuable insight, it also risks oversimplifying abuse dynamics by reducing complex emotional, social, and safety-related decisions to cost-benefit calculations. Critics argue that factors such as fear, trauma bonding, financial dependence, and social isolation may play a far more significant role than perceived investment alone.

Nevertheless, the model has practical relevance in therapy and counselling. It encourages practitioners to assess how satisfied partners are, what they have invested in, and whether they feel they have alternatives. This can help therapists design interventions that support healthy decision-making and identify when commitment may be rooted more in fear or obligation than genuine contentment. However, its applicability may be more substantial in individualistic cultures, where relational choices are framed around personal agency and emotional fulfilment rather than collective duty or familial obligation.

FALSIFIABILITY AND THE ISSUE OF CIRCULARITY

Like SET and Equity Theory, the Investment Model has been criticised for lacking falsifiability. The theory becomes overly flexible because key variables such as “investment” or “commitment” are retrospectively defined by whatever the individual values. For example, if someone stays in an unsatisfying or even harmful relationship, the theory can always explain this post hoc by pointing to high investment or lack of alternatives. Similarly, any emotional reaction—guilt, love, anxiety—can be reframed as “evidence” of commitment, making the model difficult to disprove.

This tautological structure weakens the model’s scientific status. If a theory can explain all outcomes, including contradictory ones, it risks becoming descriptive rather than predictive. While it may still be useful in applied settings, its lack of falsifiability limits its contribution to psychology as a testable scientific framework.

CULTURAL BIAS

Like many economic theories of relationships, Rusbult’s Investment Model reflects assumptions rooted in Western, individualistic societies. It assumes that commitment is based primarily on personal satisfaction, investment, and perceived alternatives. However, in many collectivist cultures, commitment may be shaped less by individual benefit and more by familial duty, religious tradition, or social expectation. These motivations may not align with the model’s cost-benefit framework, limiting its cross-cultural validity.

Moreover, what counts as a “fair” or “satisfying” relationship is not objectively universal but shaped by the zeitgeist — the social and cultural climate of the time. For example, historical norms that denied voting rights to women, working-class men, or ethnic minorities were often perceived as fair at the time due to dominant ideologies — even though they were objectively unjust. This illustrates that perceptions of fairness are socialised, not intrinsic, and may reinforce rather than challenge inequality.

In relationships, a traditional housewife or "traditional wife" may perceive her situation as equitable, even if her partner contributes less practically. The model focuses on perceived equity rather than actual balance, which makes it vulnerable to reinforcing status quo dynamics. What is seen as equitable may reflect internalised inequality. Therefore, while the model attempts to be universal, its assumptions about satisfaction and fairness are not culturally or historically neutral.

Moghaddam (1998) highlights that theories like Rusbult’s should be studied emically—within the cultural context—rather than applied etically using Western definitions of satisfaction and fairness. Without this, the theory risks misinterpreting or justifying inequality, mistaking accommodation or resignation for commitment.

GENDER BIAS

While Rusbult’s model is often praised for explaining why some women stay in abusive relationships, this application can be controversial. It implies a passive acceptance of investment and alternatives without addressing emotional, social, or financial coercion. Critics argue that framing abuse in purely economic terms may oversimplify the dynamics of control, fear, and trauma. Additionally, there is limited research on whether the model explains male behaviour in abusive or dissatisfying relationships equally well—raising the issue of gender bias or androcentric assumptions in relationship research.

OVERSIMPLIFICATION OF RELATIONSHIP DYNAMICS

Despite its improvements on earlier models, the Investment Model still assumes that individuals make fairly rational calculations about commitment. However, real relationships are often influenced by emotion, unconscious patterns, attachment styles, and personal trauma. The model does not adequately account for these more profound psychological variables. Nor does it fully explain how people can remain committed to unsatisfying relationships despite alternatives and minimal investment, suggesting gaps in explanatory power.

CAUSALITY ISSUES

The direction of causality is also unclear. Does high commitment lead people to view their investments and satisfaction more positively (a kind of confirmation bias)? Or do high investments and satisfaction create commitment? Most data is correlational, so causality cannot be reliably established.

CONCLUSION

Rusbult’s Investment Model offers a more complete and realistic explanation of relationship commitment than SET or Equity Theory by including the role of investment and recognising that people may remain in unsatisfying relationships. It is supported by research and has valuable clinical applications, particularly in explaining long-term and even abusive relationships.

However, like other economic love models, it suffers from falsifiability, subjectivity, and cultural bias. It is also limited by its reliance on self-report data and assumptions of rational calculation. Despite its strengths, it is best used with other psychological theories—such as Attachment Theory or models of emotional bonding—to offer a fuller picture of why people stay committed in romantic relationships.

OUTLINE AND EVALUATE TWO OR MORE THEORIES OF RELATIONSHIP FORMATION (6+10 MARKS)

AO1 – Social exchange theory

One theory of the maintenance of romantic relationships is the social exchange theory (Thibaut and Kelley)

It is based on the assumption that behaviour is a series of exchanges where relationships aim to maximise profits and minimise costs.

It suggests that the level of profitability determines commitment to the relationship.

AO1 – Comparison levels

It further suggests that comparison levels determine if effort should be put into maintaining the relationship.

Individuals usually have expectations of what to expect in a relationship. They maintain the relationship if they find their partner attractive and feel satisfied if their expectations are met.

They are more likely to leave the relationship if expectations are not met. If there is another potential partner, they will compare the possible benefits/costs with their current partner and leave if the alternative is more beneficial.

AO3 – Support – Simpson et al. (1990)

Research by Simpson et al. (1990) provides support for this theory

They found that when asked to rate the attractiveness of members of the opposite sex, participants in a relationship rated lower than those not in a relationship

This is indicative of comparison levels being used, where a way to overcome the potential threat to a relationship is to alter perceptions of the attractiveness of other people

AO3 – Explain abusive relationships – Rusbult and Martz (1995)

Rusbult and Martz suggest this theory can be used to explain why women may decide to stay in an abusive relationship

This may be because the profits of staying in the relationship are higher than the costs of leaving the relationship (e.g. not being able to see children or support them)

This suggests that the reason for staying is due to profit and loss

AO3 – Challenge Clark and Mills (1979)

Clark and Mills (1979) reject the assumption that relationships are based on economics.

They suggest that such economic theories are only applicable to exchange relationships where rewards and costs are tracked (e.g. work colleagues)

In communal relationships (e.g. partners and friends), people are governed by the desire to respond to the needs of others rather than incur profits.

AO1 – Equity

An alternative theory of the maintenance of relationships which addresses this issue is the equity theory proposed by Walster et al. (1978)

It suggests that individuals strive to achieve equity and fairness in relationships and feel distress and dissatisfaction if they perceive unfairness.

For example, if someone receives a lot but gives a little, they may feel distressed and not wish to maintain the relationship.

AO1 – Ratio of inputs and outputs

According to this theory, equity does not mean objective equality. Instead, equity is measured by a person’s perceived ratio of inputs, outputs, and contributions to outcomes.

For a relationship to be equitable, partners’ profits minus their losses must be equal.

If the relationship is inequitable, people are motivated to restore it by either changing the amount demanded, contributing to maintaining it or comparing the relationship with others to see if it is worth maintaining.

AO3 – Support – Stafford & Canary

Supports the assumption that equity is the foundation for successful relationships

I asked 200 married couples to complete measures of equity and relationship satisfaction.

Found that satisfaction is highest for those perceiving equity and lowest for under-benefited partners

These findings are consistent with equity theory and the assumption that mutually satisfying relationships are equitable.

AO3 – Gender differences – DeMaris (2007)

The study used couples from the US National Survey of Families and Households to investigate whether marital inequity is associated with later marital disruption.

Found that the only subjective measure of inequity associated with disruption is the woman’s sense of being under-benefited

This suggests that inequity can lead to relationship breakdown. These findings further indicate gender differences in the perception of equity, where it may only be considered to women and not men, so the theory does not apply to men.

IDA – Real-life applications

Research on this has real-life applications. It has been found that the ratios of positive and negative exchanges affect the maintenance of relationships; therefore, increasing the proportion of positive exchanges should increase relationship satisfaction.

This has prompted the formation of Integrated Behavioural Couples Therapy (IBCT), which aims to increase the proportion of positive exchanges.

Christensen et al. (2004) demonstrated the effectiveness of this therapy, as over two-thirds of 60 distressed couples reported significant improvement in the quality of their relationships.

AO3 – Cultural bias

Moghaddam suggests that economic theories like this only apply to Western relationships, specifically to individuals with high social mobility and short-term relationships (e.g. students)

There is little time to develop commitment in these relationships, so it makes sense to be concerned with give-and-take.

In long-term relationships in less mobile cultures, security is valued over profit, meaning that equity theory is inadequate to explain the maintenance of romantic relationships in all cultures.

IDA – Reductionist

Both theories can, therefore, be criticised for being reductionist

Ragsdale and Brandau-Brown claim that equity theory is insufficient as it is an “incomplete rendering of the way married couples behave and respect each other.”

This implies that marital relationships are more complex than equity theory suggests, which reduces complex behaviours due to the motivation to maintain equity.